Areté blog | Market review Q423

The fourth quarter was a blowout quarter for stocks and the conventional 60/40 (stocks/bonds) strategy. These returns salvaged what had been an unexceptional year for 60/40 and turned it into one of the best in its history. The fourth quarter spurt also improved the S&P 500 annual returns from good to terrific.

So, was the fourth quarter a portent of better things to come - or, was it an anomaly that is likely to revert? Let's take a look.

Inflation, version 1

The consensus view of the fourth quarter is that inflation has finally been defeated. The "transitory" characterization may have taken a little longer to unfold than initially expected, but eventually proved to be accurate.

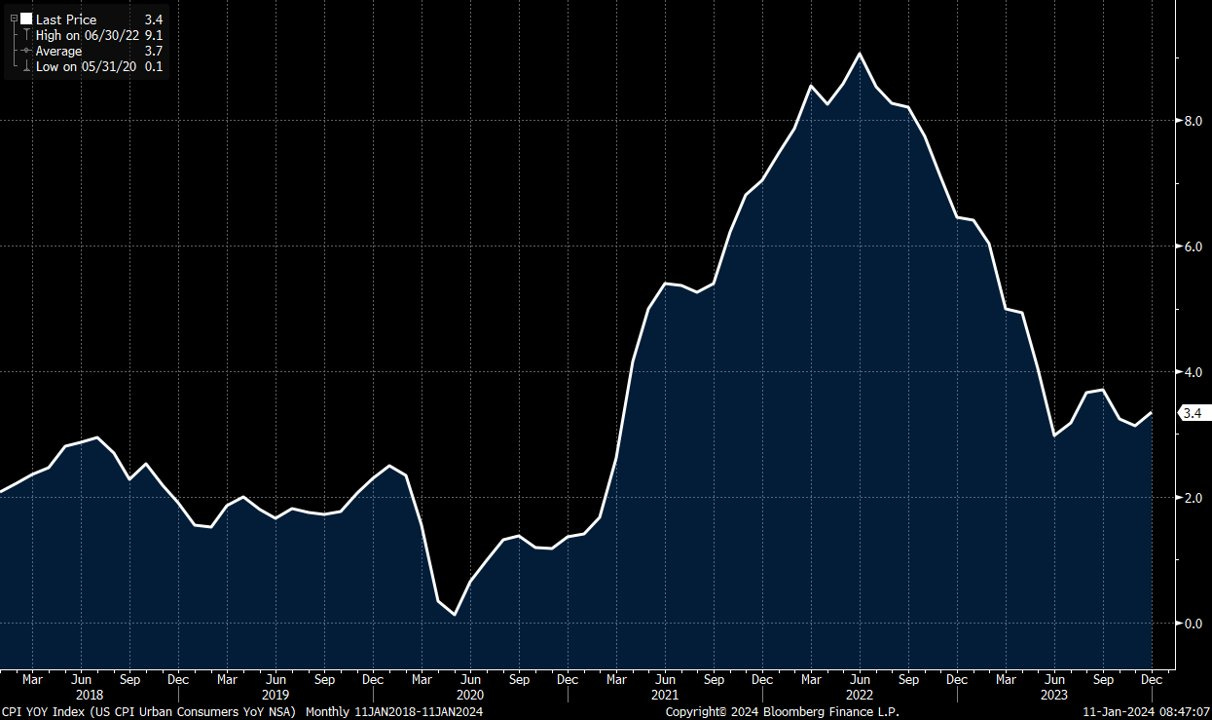

As supply chains mended after the pandemic, so too did inflationary pressures moderate. Further, while economic weakness has also taken longer than expected to manifest, it too is becoming increasingly apparent. Bankruptcies are rising. Consumer credit is spiking. Job growth is slowing down. It is all summed up with the continued decline in core consumer price inflation.

Monetary policy, version 1

Just as inflation was coming into range, monetary policy also took a turn to the softer side. It started off with the Treasury's Quarterly Refunding Announcement in early December which slightly lowered the quantity of longer-term bonds to be issued. The message received by the market was that Treasury would act to mitigate the threat of bond yields that got too high.

The Fed followed up with its own change of tune. In December the FOMC met and had every chance to talk down the likelihood of rate cuts in 2024 but didn't take it. The message received by the market was that the Fed endorsed the idea of several rate cuts in the coming year. To top it all off, the possibility of tapering the Fed's Quantitative Tightening (QT) program was also raised in the new year.

As a result, not only did the economic evidence seem to point in the direction of lower inflation, but monetary policy seemed to endorse that view as well. One could almost hear the echoes of Mario Draghi's "Do whatever it takes" speech and imagine the “Goldilocks” environment for risk assets that it inaugurated.

Inflation, version 2

While the “Goldilocks” scenario is certainly one plausible account of fourth quarter developments, it is not the only one. Another account, which is also eminently plausible, is that inflation is stuck at a higher level. As Ben Hunt highlights on X, “CPI bottomed last June. I don't know why this is so difficult for people to understand.”

Further, it’s not just CPI that suggests an environment of higher inflation. As I have been reporting (most recently in the Outlook piece), the greater concern for long-term investors is debasement through the monetization of excess spending. Michael Howell at CrossBorders Capital ($) also recently highlighted the problem: “Looking ahead our huge debt burden requires a sizeable monetary inflation to keep pace.”

John Plender at the FT also picked up on the notion that longer-term inflation prospects involve more than just current CPI readings:

Harvard’s Kenneth Rogoff argues that even if inflation declines it will probably remain higher for the next decade than in the decade after the financial crisis. He cites factors including soaring debt levels, increased defence spending, the green transition and populist demands for income redistribution.

Monetary policy, version 2

In addition, just as there is a different, and eminently plausible, take on inflation, so too is there a different, and eminently plausible interpretation of monetary policy actions in the quarter.

While it is true that monetary policy took center stage for promoting growth after the GFC, its role changed after the pandemic. When the pandemic hit, the Fed unleashed liquidity, but did so primarily for the purpose of preventing a melt-down in Treasury markets or a financial crisis. The growth mandate was taken over by government deficit spending.

Later, after supply chains got jammed up and energy prices rose after Russia invaded Ukraine, inflation suddenly became a constraint the Fed had not had to contend with for a long time. This constraint became all the more problematic in the context of growing deficits.

The bottom line is the monetary policy reaction function changed in an important way. Whereas liquidity had been used to advance growth, now it is being used (primarily) to prevent instability. Now, we can take a fresh look at monetary policy actions in the quarter from this perspective.

For starters, while the Treasury’s pull back on bond issuance sent a message, timing was also part of that message. Namely, the dramatic decline in 10-year yields provided a fortuitous window for banks and financial organizations to unload underwater bonds right before year-end reporting. That would be good for financial stability.

Concern about financial stability is also a plausible rationale for the proposal to taper QT. As the argument goes, reserves are spread unevenly and as a result, some banks may be bumping up against a comfortable level of reserves. As Matt Klein highlighted ($), “Fed officials want to make sure they do not inadvertantly [sic] deprive the banking system of an essential asset necessary to lubricate the flows of commerce.” Tapering QT would allow the Fed to mitigate that risk.

Finally, the Fed’s endorsement of several rate cuts in 2024 may also have more to do with preserving financial stability than with a “Mission Accomplished” message on inflation. Most economists expected a recession last year but didn’t get it. That doesn’t mean that higher rates haven’t affected businesses; it just means higher rates are taking a bit longer to bite.

If that’s the case, bad debts will be eroding money supply just as Treasury needs to ramp up its issuance of debt. While inflation is unpleasant for monetary officials, the threat of dysfunction in the Treasury market is what keeps them up at night.

In sum, Fed and Treasury actions in the fourth quarter may have appeared to endorse a view of moderating inflation, and that may have been one motive, it is also possible to view such actions as primarily oriented to financial stability. While this perspective is not consensus, it is not outlandish or conspiratorial either. In John Plender ‘s words:

Despite the markets’ cheery recent assumption about waning inflation, the protracted era of ultra-low interest rates is surely over. Yes, short-term rates will fall in 2024 as inflation continues to decline. But the longer term is another matter.

Story-telling

So, there are two different, yet plausible, outlooks for inflation and there are two different, but plausible, scenarios for the reaction function of monetary authorities. The challenge for investors is to weigh these competing perspectives against one another to determine whether markets will be off to the races or about to sink.

That challenge is made all the greater due to the power of narrative to shape the way we think about such things. As analysts we can try to analyze information as objectively as possible, but so much of that information is contrived in some way. Ben Hunt describes how narrative shapes the information we consume:

The significance here is not in the real world but in Fiat World, where reality is given to us by declaration rather than experience. The significance is in the effort [to reframe the inflation narrative] that Big Media, Big Tech and Big Politics make to shape the way we think. It’s not a lie, per se, but it’s not a truth, either. It’s all just story, all the way down, not just in their words but in their pictures too.

By the way, there is no doubt the Biden administration and the Fed would like us to believe inflation is vanquished. There is also no doubt Wall Street wants us to believe it is a great time to buy stocks and bonds. None of that makes it so, however. As Hunt suggests, it is important to “look through the story-telling”.

Conclusion

One of the interesting elements of the current market environment is that despite the mixed evidence on inflation, despite the mixed motives of monetary authorities, and despite the obvious self-interest in promoting a narrative of easing inflation and monetary policy, consensus is betting overwhelmingly on one outcome. The current consensus view seems to reflect an unusual belief in low inflation and to demonstrate an unusual fealty to the narrative of liquidity-driven tailwinds for risk assets.

While it is possible this view is correct, it is also very possible it is not. That makes the consensus view vulnerable.

It also means there could be an interesting opportunity to do something different. If and when liquidity becomes insufficient to continue fueling the rise in stocks, marginal buyers will need more compelling economic and fundamental evidence to justify stock prices. That will change a lot of things.