Arete's Observations 10/16/20

Market observations

After posting a couple of strong weeks, stocks finally eased up this week. While hopes of a new stimulus bill before the election had increased, they have since faded. While Biden increased his lead after the debate, concerns of a contested election have returned.

To top it all off, concerns about the coronavirus had faded considerably but now seem to be increasing again. I can attest from my experiences in and around Philadelphia that people are considerably more lackadaisical about social distancing and other safety protocols than a few weeks ago. This seems to be a thing. Just as we are entering flu season, complacency is on the rise.

Germany has been towards the top of the list in its handling of the coronavirus. The fact that its experience looks a lot like a second wave does not bode well for the rest of the world.

Economy

Hoisington Quarterly Review and Outlook Third Quarter 2020

https://www.hoisingtonmgt.com/pdf/HIM2020Q3NP.pdf

“Debt financed fiscal programs only boost the economy in the very short-run, but ultimately reduce growth.”

“The secular deterioration in economic growth has created a condition of excess resources and disinflation.”

Lacy Hunt is one of the sharpest people out there on the economy and as usual, he doesn’t mince words. He calls the debt financed fiscal support a long-term impediment to growth rather than “stimulus”. He also describes the economy as being in “secular deterioration” rather than hypothesizing about the shape of recovery. The broader point, and it is a very fair one, is that you need to call things like they are to get the longer-term investment implications right.

Sports

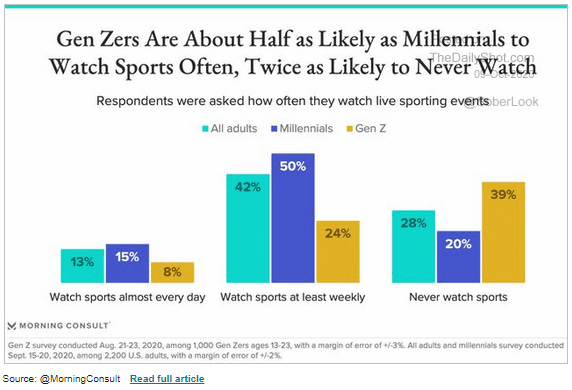

One business that may be in for some changes is that of professional sports. While the pandemic has affected the experience of watching sports in the short-term, in the longer-term there is evidence of lower demand due to demographics: Gen Zers have significantly less interest. Maybe those leagues and the sports networks that cover them will need to modify their business models a bit?

Energy

Shale binge has spoiled US reserves, top investor warns

https://www.ft.com/content/aad9c356-b37e-4768-b39f-c22b9548b290

“’That’s the dirty secret about shale,’ Mr VanLoh told the Financial Times, noting wells had often been drilled too closely to one another. ‘What we’ve done for the last five years is we’ve drilled the heart out of the watermelon’.”

“He said they would have to improve ESG ‘because ultimately you’re not going to get capital from us if you don’t . . . And we won’t be able to get capital from our limited partners if you don’t’.”

This shouldn’t be too surprising – give oil companies free capital and they drill more than they should. Regardless, this is a useful status update of the shale industry.

The explicit recognition of the impact of ESG on the energy industry is another interesting nugget. This is a good example of just how influential ESG efforts are becoming. While I welcome the scrutiny they provide to an industry that needs it, I also harbor concerns about overreach.

What is really needed is a strategic energy policy that maps out a long-term migration away from fossil fuels. Absent that, there is a very good chance that energy supplies get disrupted at some point. Just as energy was overproduced, it can be underproduced as well.

Public policy

How to diagnose your own Dutch disease

https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2019/03/13/1552487003000/How-to-diagnose-your-own-Dutch-disease/

“Now: imagine you are the Secretary of the Treasury of the United States of America. For ‘cobalt-rich ore,’ substitute ‘dollars,’ or ‘dollar-denominated assets,’ or perhaps just ‘Treasuries.’ You still need to worry about Dutch disease.”

“So if the US has Dutch disease, from reading Robinson et al (2006) we'd expect for the value from the creation of new federal debt to be distributed as patronage, to a small group of people with access to power. We'd expect the federal government to over-produce debt, without considering long-term value or sustainability of production. And we'd expect the right to produce debt to raise the value of being in power.”

So, Dutch disease describes a paradox that often occurs in developing countries. A body of natural resources is discovered which should bring the country good fortune. Instead, however, the country ends up being worse off for it. A number of factors have been attributed as potential causes and most of them relate to poor governance in some way.

The FT’s Alphaville makes a tongue-in-cheek proposition: Perhaps the U.S. should be concerned about Dutch disease due to its natural resource of dollars. Could the U.S. actually be worse off for its ability to print dollars? The hypothesis explains rising inequality, increasing debt, and increasing political polarization. Hmm, maybe they have a point.

Monetary policy

Time for the Federal Reserve to step up

https://www.ft.com/content/ef1a7c4e-eb22-4cab-b699-929e520d3c8c

“But at this point, the Fed is faced with a collapse of one of its dual mandates, which is employment. US states and localities have balanced budget laws and, at the end of the year, they will have to lay off large numbers of employees. The country does not need that.”

This assessment leads John Dizard to believe the Fed will need to make substantial amounts of credit available to states and municipalities. With their budgets bludgeoned by the pandemic and laws requiring those budgets to be balanced, this does put the Fed in an incredibly awkward spot.

If it does not provide credit to the states under the auspices of maintaining maximum sustainable employment, it can be accused of violating its dual mandate. If it does, however, it creates a dangerous precedent. At what point would credit provision stop if jobs were potentially at stake? This could be a very meaningful step in monetary policy and I have heard nobody else discussing it.

Technology

The rush to constrain the power of Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google

https://www.ft.com/content/a840e4df-6a24-4ff0-8cd4-0931a135fe02

“In Washington, members of the House antitrust committee have been pondering three possible responses [to the power of Big Tech]: throw more resources at enforcing existing antitrust rules; tighten up the laws to give the enforcers more teeth; or design entirely new regulatory frameworks with the most powerful digital gatekeepers in mind.”

“Their answer, in a 449-page broad side against Big Tech released this week, is: do all three.”

Vertigo Integration, Almost Daily Grant’s, Thursday, October 8, 2020

https://www.grantspub.com/resources/commentary.cfm

“A draft response from Republicans on the committee termed the report ‘a thinly veiled call to break up’ the tech giants.”

“… there is clearly a bipartisan conclusion that these companies are acting anticompetitively.”

There has been talk of Big Tech garnering too much power for many years. I believe it is true and I also believe it has stymied competition and innovation. Nonetheless, between a lack of political interest to pursue the issues, and deft handling of the political landscape, the Big Tech companies have enjoyed a wonderful environment to grow.

Well, easy until now anyway. For some reason “politicians and regulators in Washington seem to be almost falling over each other to make up for lost time”. My guess is the Big Tech stocks should be discounting a more intrusive regulatory presence than they currently are.

Environment, Social, Governance

ESG Drives a Stake Through Friedman's Legacy

“there is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception fraud.”

“But ESG factors often are touted for reasons that are nonpecuniary—to address social welfare more broadly, rather than maximize returns.”

I have had an interest in what used to be called socially responsible investing (now ESG) for a long time and reported on the subject in business school. I find the intersection of business and social protocols fascinating – and important. While there was only peripheral interest in the subject at the time, the interest in ESG is becoming an influential force.

This makes it all the more important to really understand the issues. The first quote, by Milton Friedman, certainly bears weight due to his stature as an economist, but also reveals the magnitude of his naivete in business matters. What exactly are the “rules of the game”? What if penalties of operating outside of them are negligibly small? What if companies become so powerful as to write the rules of the game? In short, Friedman was too arrogant in assuming these are straightforward issues.

On the other hand, many ESG fans go so far in their advocacy of social welfare and other nonpecuniary efforts as to substantially undermine any notion of “investment”. That is not the right balance either.

Recognizing an opportunity to step up, the Business Roundtable put out a statement on ESG a year ago. With no effort to establish accountability, the exercise amounted to little more than virtue signaling.

I still absolutely think there is a place for ESG and believe the right place is somewhere in the middle. As an analyst, I have observed that companies that are consistently bad actors normally receive payback in some form. And it is frequently costly. Treat your customers badly enough for long enough and they will find other places to go. Indeed, that goes for any of a company’s stakeholders.

The way I have envisioned this from a financial perspective is that lower quality companies deserve a higher cost of capital. Conversely, higher quality companies deserve a lower cost of capital. Although assessing that cost is a somewhat arbitrary exercise, the approach reconciles both the importance of ESG goals with the distinct potential for them to also be of investment merit.

Inflation

One of the mistakes that I hear repeatedly in arguments about inflation involves the difference between short-term price phenomena and long-term structural issues. Many commentators have used supply disruptions prompted by Covid-19 as anecdotal evidence to support a case for longer-term inflation. Much of this is wrong. It is certainly misleading.

Lumber is a great example, but there are many. Lumber prices shot up early in the pandemic as both demand and supply received jolts. Demand got a short-term boost as many people started leaving dense (and expensive) urban centers for more livable places elsewhere. Others were spending a lot more time at home and compelled to do renovations. At the same time, supply was constrained by reduced operating capacity and supply chain disruptions.

The result of these temporary disruptions was a short-term increase in lumber prices. Short-term. In order to have a longer-term inflationary impact, the disruptions would have to be viewed as creating longer-term imbalances. Those imbalances are better captured by measures such as capacity utilization.

Factory capacity utilization was 73.6% in March before falling to 64.1% in April. Obviously, the big drop suggests there was significant excess capacity available. This points to deflationary, not inflationary pressures. By August, capacity utilization recovered to 71.4%, but was still below its level in March. While this is only one metric, it is indicative of the structural balance of supply and demand which is more indicative of long-term trends.

Investment advisory

B-Ds Many Times More Likely to Recommend Complex Products Than RIAs

“But the biggest difference between RIAs and broker-dealers was in the rate of recommending complex products.”

“When complex products were sold, broker-dealers were twice as likely as investment advisers to recommend the purchase of leveraged and inverse ETFs, seven times as likely to recommend private placements, eight times as likely to recommend variable annuities, and nine times as likely to recommend non-traded REITs.”

The landscape for advisory services has changed a lot in the last ten to fifteen years. Historically brokers provided investment advice although they were never obligated to do so in way that was in the client’s best interest. After the financial crisis, the registered investment advisor (RIA) model became much more popular because of its design for serving investors in a more fiduciary capacity.

Although there is nothing that inherently makes the broker model “bad” and the RIA model “good”, there are different incentive systems that often nudge the relationship with clients in a certain direction. The quotes above provide evidence that many of these are still in place. Because brokers get compensated by commissions, they have incentives to sell more complex, and therefore more expensive products. This reveals a structural conflict of interest that can cause investors to pay more for financial services than they should.

Who do Americans Turn to the Most for Financial Guidance? Not FAs.

“When Americans need help with their personal finances, they are most likely to seek advice from people around them — or no one at all — rather than from financial professionals, a recent survey finds.”

“Nearly 40% of the survey respondents would go to parents, family, friends or coworkers for financial guidance …”

Despite the advances of the RIA model, there is still a great deal of confusion as to what a financial advisor is and how they do their work. As a result, when misdeeds are done, the lack of trust often falls uniformly across the industry. This is changing, but slowly. While it creates opportunities for competent and well-intended advisors, widespread lack of trust serves as an obstacle to a more rapid proliferation of new (and better) offerings.

Money management

Value fund manager AJO to shut down after losses

https://www.ft.com/content/c6cf8171-30e8-4ed3-9692-a850cc75ef72

“’The drought in value — the longest on record — is at the heart of our challenge,’ he wrote. ‘The length and the severity of the headwinds have led to lingering viability concerns among clients, consultants, and employees’.”

For one, it is a shame that AJO is closing. Ted Aronson is one of the most gracious and honorable people in the business so it is an especially unfortunate loss for the industry.

While the underperformance of the value style has been widely recognized, this event certainly highlights the harshness of the environment. I think it also highlights the harshness of the environment for active management.

As a quant shop, AJO focused on idiosyncratic value markers. As passive investing has come to dominate market activity, however, those markers have become much less effective. Instead, what used to be idiosyncratic risk for stocks has been transmogrified into systemic risk for the market as a whole. I discussed one element of this phenomenon in my latest blog post. It won’t be fun when that systemic risk gets unleashed, but then it hasn’t been fun for active managers waiting for it to happen either.

Decision making

Lessons from the endowment model

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2020/10/03/lessons-from-the-endowment-model

“In the weeks following the stock market crash in October 1987, the investment committee of Yale University’s endowment fund convened two extraordinary meetings. Just after the crash its newish chief investment officer, David Swensen, had bought up stocks (which had become much cheaper) paid for by sales of bonds. Though in line with the fund’s agreed policy, this rebalancing appeared rash in the context of the market gloom—hence the meetings. One committee member said there would be ‘hell to pay’ if Yale got it wrong. But the original decision stood. And it paid off handsomely.”

“The other big lesson is that, once an investment policy is agreed upon, the smart people have to be allowed to execute it. This comes under the dry heading of ‘governance’, but it is crucial. It is emotionally taxing to buy risky assets when everyone else is gloomy or to sell them when others are giddy. And, as Mr Swensen’s tale from 1987 shows, an institution with even the longest horizons can be tempted to think short-term.”

This is a great anecdote and a particularly instructive one as well. For one, even if you are literally the next David Swensen, you will get push back from investment committees and other constituents. That doesn’t mean they are right.

Another underappreciated point is the importance of decision making and governance. So much time, effort, and money are devoted to finding the greatest expertise out there. None of that matters much, however, if those smart people are not allowed to do their jobs. The practical implication is that many “long-term” investment funds are unduly constrained by poor governance and that handicaps performance. Conversely, many individuals may not have access to high tech investment tools but can do quite well by making good decisions with what they have.

Implications for investment strategy

As I mentioned in the “Market Observations” segment, a number of indicators have been turning down recently and from what I see there are more to come. Nonetheless, stocks have glided higher on the thinnest of narratives and the largest of valuations. That sounds like trouble brewing to me.

I am most concerned that several big problems are already too far gone to avoid significant pain. A great deal of the temporary employment over the summer has become permanent unemployment. There is a huge base of commercial real estate that has not yet started to reprice lower. Further, while most companies were content to play through in the summer, they are now adjusting to the weaker economic outlook by making more permanent cuts.

This would be bad enough on its own, but in front of an election, there is little chance now anything substantive can get done soon. As a result, the problems will worsen. Further, there are few election scenarios that would facilitate quick and decisive action.

In sum, I think the chances of a significant market disruption are fairly high. This implies being very defensive for the time being while preparing for a new landscape for stocks. This could get interesting.

Principles for Areté’s Observations

All the research I reference is curated in the sense that it comes from what I consider to be reliable sources and to provide meaningful contributions to understanding what is going on. The goal here is to figure things out, not to advocate.

One objective is to simply share some of the interesting tidbits of information that I come across every day from reading and doing research. Many of these do not make big headlines individually, but often shed light on something important.

One of the big problems with investing is that most investment theses are one-sided. This creates a number of problems for investors trying to make good decisions. Whenever there are multiple sides to an issue, I try to present each side with its pros and cons.

Because most investment theses tend to be one-sided, it can be very difficult to determine which is the better argument. Each may be plausible, and even entirely correct, but still have a fatal flaw or miss a higher point. For important debates that have more than one side, Areté’s Takes are designed to show both sides of an argument and to express my opinion as to which side has the stronger case, and why.

With the high volume of investment-related information available, the bigger issue today is not acquiring information, but being able to make sense of all of it and keep it in perspective. As a result, I describe news stories in the context of bodies of financial knowledge, my studies of financial history, and over thirty years of investment experience.

Note on references

The links provided above refer to several sources that are free but also refer to sources that are behind paywalls. All of these are designed to help you corroborate and investigate on your own. For the paywall sites, it is fair to assume that I subscribe because I derive a great deal of value from the subscription.

Comments

Please direct comments or feedback to drobertson@areteam.com.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.