Areté's Observations 6/18/21

Areté (Pronounced ar-uh-tay) 1. Goodness or excellence of any kind. Fulfillment of purpose or function, the act of living up to one’s potential. 2. Effectiveness, knowledge.

Some beautiful June weather this week combined with significantly reduced pandemic restrictions to create a refreshing sense of normalcy. This was fortunate because the eerie sense of calm pervading the market started cracking after the Fed meeting on Wednesday …

Market observations

Last week inflation came out at the highest clip yet, but rates came down and VIX hit its lowest level since the start of pandemic. Go figure.

Perhaps the most useful takeaway is to observe the degree of difficulty in playing short-term inflation themes has increased considerably. For instance, CAT is a quintessential reflation stock, but has gotten hammered since early June. This result speaks partly to the fact that a lot of activity has been driven by short-term trading and partly to the very mixed evidence on inflation right now.

Labor

"Great resignation" wave coming for companies

https://www.axios.com/resignations-companies-e279fcfc-c8e7-4955-8a9b-47562490ee55.html

“Workers have had more than a year to reconsider work-life balance or career paths, and as the world opens back up, many of them will give their two weeks' notice and make those changes they’ve been dreaming about.”

“Surveys show anywhere from 25% to upwards of 40% of workers are thinking about quitting their jobs.”

This resignation phenomenon is interesting and one I have seen crop up in several places the last couple of weeks. It does beg the question of why so many people are considering quitting their jobs now.

The Economist hypothesizes “bullsh*t jobs” may be part of the cause. In other words, “Employees who think their work is useless tend to feel anxious and depressed.” Not hard to imagine. Certainly, less time in the office provided more time for introspection. Axios adds: "some are deciding they want to work fewer hours or with more flexibility to create more time for family or hobbies.”

David Brooks added his two cents’ worth in the New York Times: “The biggest shifts [from the pandemic], though, may be mental. People have been reminded that life is short … Millions of Americans seem ready to change their lives to be more in touch with their values.”

While the causes are probably many and diverse, the impact will be similar. A lot of companies will have to contend with the costs and frictions of higher turnover and even more importantly, deal with the potential loss of a great many experienced people. Ultimately this is likely to make work life better for employees but is likely to make labor a bigger problem for employers.

Housing

With house prices continuing to run up, inventory at record lows, and sales being made in record time, it’s no wonder buying conditions have plunged precipitously. While the frenzy to buy a home continues for the time being, it is rapidly losing steam. A very similar dynamic is happening with used vehicles.

One takeaway is the phenomenon corroborates the old saying, “the solution to high prices is high prices”. One way or another, those high prices will eventually create incentives for demand to decrease and/or supply to increase. The main questions are how long will it take and what path will it take? Will the transition be fairly quick and smooth or longer and bumpier? Given the amount of economic uncertainty and the degree of policy intervention, I vote for the latter.

Credit

Zombies Are on the March in Post-Covid Markets ($)

“A little more than a year ago, we were worried about a solvency crisis. With so many companies suddenly deprived of their revenue, it seemed only reasonable to fear that a wave of bankruptcies and defaults would choke the banking system, bring asset prices down, and present us with a secondary financial crisis to follow the public health crisis of the pandemic.”

“The year-on-year change looks even more deviant. Outside of the distortions caused by the law change, it’s the biggest reduction in the number of bankruptcies so far this century — during a brief but brutal recession. How can this even be possible?”

When the pandemic lockdowns began in March of last year I was very much in the same camp as John Authers believing there would be a solvency crisis. Looking back, the numbers show that position was not only wrong but almost completely opposite of what happened.

The question now is how to interpret those results. One interpretation is the solvency concerns were overdone and should be discredited. Another interpretation is the solvency concerns are valid but have been deferred. Essentially, public policy put all the main negative consequences of shutting down the economy on “pause” until the coronavirus was behind us. I favor the second interpretation and believe the first one creates a great deal of potential for harm.

A key assumption behind the insolvency argument was free markets would be allowed to function. That assumption turned out to be wrong. When presented with the potential for massive economic displacement in an election year, the government not only threw wads of money at the problem, but also prevented most instances of bad debts to be reckoned with.

While that level of involvement prevented worse things from happening, it has also created a number of risks going forward. One is uncertainty. The threshold for policy interventions is now lower and the magnitude is greater than ever before. What will happen the next time there is a downturn? It is hard to say, but the distribution of possible outcomes is massive.

Another pitfall is moral hazard. On a relative basis, the people who faired best after the pandemic hit were those who took the greatest risks. It is not hard to see how an incentive to take even bigger risks when the situation is worst can lead to terrible outcomes.

One thing to keep in mind is downturns often begin with crises in private credit markets. With rates at record lows while the bans on evictions and foreclosures and repayment of student debt are finally allowed to expire, there is a good chance we start seeing what happens when the “pause” button is released.

Analytical lessons

Humans are imperfect, inconsistent decision-makers ($)

“Noise is unwanted variation in judgments that should be identical, which leads to inaccurate and unfair decisions. It is all around people all the time, though individuals fail to notice it.”

“The problem of bias in decisions is well known and there are strategies that people can adopt to minimise it … But noise is different precisely because it is less apparent. ‘It becomes visible only when we think statistically about an ensemble of similar judgments’.”

This article from the Economist is a review of the new book, Noise, by Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony and Cass Sunstein. While Kahneman’s earlier work, Thinking, Fast and Slow, did a great deal to illuminate the systemic error of bias, the exploration of noise in analytical efforts is a useful addition.

A classic example is talking on a phone. If there is a lot of static or background noise, it can be hard to make out what the speaker is saying. In the same way, with many economic numbers being distorted by the pandemic, it can be hard to make out what the underlying economic signals are.

The lessons are also similar. When there is more noise, you either need to work harder to establish the signal or you need to reduce the expectation you are properly receiving the signal. Neither of these adjustments seem to be occurring to any great degree by investors right now.

Economic theory

Alice’s Adventures in Equilibrium

https://www.hussmanfunds.com/comment/mc210614/

“Likewise, international trade can have features that amplify systemic inequity or impose uncompensated harm to others. All of these are “externalities.” In these cases, a free market will produce too much of the activities that produce negative externalities, and insufficient amounts that produce positive externalities, unless policies are introduced to impose private costs for harmful activities or subsidize beneficial ones (e.g. carbon taxes, investment tax credits, applying sales or value-added taxes to out-of-community purchases and reinvesting them back into the community). Nobel economist Ronald Coase demonstrated policies that ‘internalize’ these externalities can enable competitive free enterprise to produce more efficient outcomes with no loss of overall welfare.”

“However, in any setting where the marginal cost of producing each additional unit declines with the level of output, simply obtaining more customers is sufficient to enhance profits. In this case, neither limited supply nor high prices are required, yet the company may enjoy the status of a ‘natural monopoly’.”

These quotes are just a couple of snippets but capture a much larger idea that John Hussman rightfully addresses: There are a number of characteristics of our economic system that distribute rewards unfairly. Moreover, this isn’t just about equitability; it is also about economic efficiency. In too many cases, markets are neither competitive nor free.

More specifically, the “level of profits” in certain situations “may have little relationship to the contribution of the entrepreneur”. Hussman lists several factors that can cause such distortions such as “network effects, social dynamics, and general technological efficiencies that were no part of the entrepreneur’s invention” and can be considered public goods.

As Hussman highlights, “A careful understanding of free enterprise must also consider ‘externalities’ where the behavior of an individual or company imposes costs to others that they do not bear (e.g. pollution), or provides benefits to others that they do not fully capture (e.g. education, scientific research).”

Hussman’s brilliant analysis is much more than just a clever abstraction; it also has far-ranging economic implications. For one, it rips apart widespread beliefs like “pay for performance” when “performance” is substantially comprised of externalities. For another, it homes in on how to differentiate between entrepreneurial skill and monetary outcomes. Hint: many entrepreneurs are better at exploiting externalities than creating valuable inventions.

Finally, the highlight of various externalities and public goods reveals an important challenge and opportunity. The challenge is some business leaders work to create natural monopolies that inhibit creative development of new ideas and technologies. Think the “kill zone” of the big tech companies that either buy-out new competitors or drive them out of business. The opportunity is to reduce such artificial barriers to entry for swarms of brilliant minds and budding entrepreneurs. This takes on even greater relevance with the appointment of Lina Khan to chair the FTC.

Public policy

Democrats and Republicans unite! At least against China.

https://www.gzeromedia.com/democrats-and-republicans-unite-at-least-against-china

“This week, the US Senate passed the so-called Endless Frontier Act, a $250 billion investment in development of artificial intelligence, quantum computing, the manufacture of semiconductors, and other tech-related sectors. The goal is to harness the combined power of America's public and private sectors to meet the tech challenges posed by China.”

“In its current form, this is the biggest diversion of public funds into the private sector to achieve strategic goals in many decades. The details of this package, and of the Senate vote, say a lot about US foreign-policy priorities and this bill's chances of becoming law.”

One of the tailwinds nudging concerns about inflation higher has been profligate fiscal spending. Ambitious plans to do even more have been significantly checked by partisan opposition, however. This corroborates a point I have been making since before the election: Partisanship is so great as to be a limiting factor on what Congress can be expected to spend in a practical sense.

This update on the Endless Frontier Act changes the logic, however. By identifying a common “enemy”, Democrats and Republicans have found a pretense under which they can unite and spend money. While $250 billion is a mere fraction of the Biden administration’s opening requests for infrastructure, it is still a very substantial sum.

Two implications arise from this development. One, if competition with China is the magic key that unlocks the spending door, we can expect to see a lot more spending bills passed on the pretense of winning the competition with China. I wouldn’t be at all surprised to see a lot of infrastructure spending re-branded as such. The second implication is such a narrow objective is quite likely to lead to much greater state control of the economy. After all, the definition of what constitutes important threats and how money gets allocated to them will become functions of the government, not free markets.

Inflation

The talk for much of this year has been about rising inflation. The graph below shows the inflation proxy, the 5-year inflation swap, rising steadily through mid-May and then dropping off. Interestingly, a new ETF designed to benefit from inflation, has continued to rise, albeit at a lower trajectory, even after the inflation measure rolled over. So which measure should we believe?

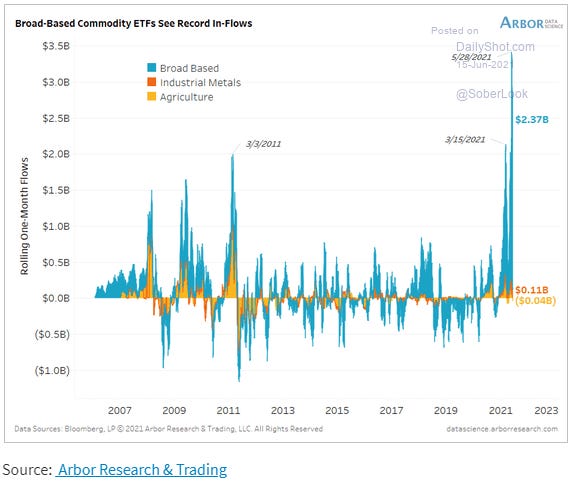

The graph below provides a strong clue. Although there is certainly a case to be made for longer-term inflation, the narrative around the subject heated up this year and precipitated large money flows into commodity funds. As a result, it is hard to tell if those flows were motivated primarily by longer-term concerns or by short-term opportunities.

This will be one of the bigger tactical challenges this summer. If most of the appreciation has been driven by short-term trading opportunities, there will be plenty of room for commodities to go down (a lot!) when momentum slows and/or reverses. With major turns in products like lumber and copper, there is evidence this is already happening.

On the other hand, continued strength in the inflation fund may be more of an indication of long-term positioning relative as opposed to the shorter-term trades in pure commodities. If that is the case, then any interim weakness in commodities creates an opportunity to build longer-term exposures. It could be a very interesting summer as this story plays out.

Gold

The boundary between crypto and fiat money is becoming more permeable ($)

“This insight applies to certain assets that lack intrinsic value. The investment case for gold, said Schelling, can best be explained as a solution to a co-ordination game. Gold bars have value because enough people tacitly agree that they do.”

One of the points about gold that I believe slips past many investors is how prominent it is globally as a store of value. The fact that so many people around the world agree on this makes it a nearly universal value. I think it is hard to overstate how useful this quality is in the effort to preserve one’s wealth.

Monetary policy

The big news coming into the week was the FOMC meeting on Wed. The landscape for that meeting was the existence of the easiest financial conditions (by far) in the last 13 years. Those easy conditions have been evidenced by rising asset prices almost everywhere one looks and desperately low yields.

Although virtually no new insight came out of the meeting, the slightest hint that sentiment for rate hikes is increasing sent stocks lower, the dollar much higher, gold plummeting, and 5-year Treasuries to one of the worst selloffs in the last ten years. The key takeaway is after setting baseline expectations for monetary policy to be exceptionally easy, any fractional deviation in the other direction causes ructions. This is an early hint of the incredibly difficult position the Fed is in.

Implications for investment strategy

Robots Are Making Us All Buy Overvalued Bonds

“Last week I [John Authers] raised the question of why bond yields managed to stage a significant decline around the highest inflation reading in decades.”

“What can possibly have driven such enthusiasm for bonds over the last 12 months? Are people mad?”

“It turns out that I’m [Aneet Chachra] among the investors buying low-yield bonds. Also, about 5% of the account is allocated to a diversified international bond fund. Roughly 60% of its holdings are in Japan/Europe, so we’ve been inadvertently investing 3% of our kids’ educational savings in no-yield bonds.”

John Authers’ analysis is a pretty good illustration of some of the perversity in the market right now. Those wondering where all the demand for overvalued US Treasuries is coming from only have to look at themselves. Through target date funds and other conventional savings programs, a certain portion of bonds is maintained whether those bonds are attractive on investment merits or not. As Authers puts it: “Automatic asset allocation rules governing savings and pension plans are driving purchases that appear to make no sense.”

This really highlights the tyranny of passive investing. When markets are cheap, passive investing offers a low-cost way to ride the wave back to more reasonable valuation. When markets are expensive, passive investing keeps plowing money into securities that are incredibly overvalued. For all but the longest of time horizons or most nimble of traders, this vastly increases the chances of experiencing poor returns.

Worse yet, passive investing has no mechanism to adapt. Indeed, this is quite likely why markets have been so complacent about inflation as evidence has continued to build. If inflation were to suddenly hit 10% tomorrow, passive funds have no capacity to perform evasive maneuvers and would continue buying stocks and bonds at exactly the same pace.

One lesson for investors is that the enormous penetration of passive investing is unlikely to reverse any time soon. As a result, any market moves that respond to inflationary or other negative signals will likely be muted by continued flows into those funds. Another lesson, however, is that passive investing cannot change economic reality. Sooner or later, the valuation “dyke” will burst, and losses will be experienced. The only way to avoid that possibility is to actively do something different.

Principles for Areté’s Observations

All the research I reference is curated in the sense that it comes from what I consider to be reliable sources and to provide meaningful contributions to understanding what is going on. The goal here is to figure things out, not to advocate.

One objective is to simply share some of the interesting tidbits of information that I come across every day from reading and doing research. Many of these do not make big headlines individually, but often shed light on something important.

One of the big problems with investing is that most investment theses are one-sided. This creates a number of problems for investors trying to make good decisions. Whenever there are multiple sides to an issue, I try to present each side with its pros and cons.

Because most investment theses tend to be one-sided, it can be very difficult to determine which is the better argument. Each may be plausible, and even entirely correct, but still have a fatal flaw or miss a higher point. For important debates that have more than one side, I try to represent both sides of an argument and to express my opinion as to which side has the stronger case, and why.

With the high volume of investment-related information available, the bigger issue today is not acquiring information, but being able to make sense of all of it and keep it in perspective. As a result, I describe news stories in the context of bodies of financial knowledge, my studies of financial history, and over thirty years of investment experience.

Note on references

The links provided above refer to several sources that are free but also refer to sources that are behind paywalls. All of these are designed to help you corroborate and investigate on your own. For the paywall sites, it is fair to assume that I subscribe because I derive a great deal of value from the subscription.

Comments

One goal of this letter is to provide fairly dense information content – so you don’t waste your time filtering through a lot of fluffy verbiage. A consequence of that decision, however, is sometimes things may not be as understandable as they could be.

If you have a general question that may also be useful for others to know the answer to, please make a comment in the newsletter and I will do my best to answer the question or make a clarification. If you have a more specific question, please send it to drobertson@areteam.com.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.