Blog post| Inflation watch

Ever since the financial crisis in 2008, extraordinary monetary policies have been in place to prevent an ugly and debilitating decline in economic growth. Despite such policies, and to some extent because of them, growth has remained below par and inflation has remained quiescent.

Since the coronavirus pandemic struck earlier this year a new inflationary dynamic has been layered on top of the old one: The immovable object of deflationary demand destruction has encountered the unstoppable force of substantially increased money supply. The outcome and timing of that confrontation will determine inflation levels and investment results for a long time to come.

Stocks look great

Judging by market activity times could hardly be better. Stocks have risen steadily since lows set in March and neither election uncertainty nor rapidly increasing infection counts have been able to derail the progress. Further, retail investors also appear to be regaling in the momentum with the additional benefit of being unencumbered by annoying commissions.

The exuberance was echoed by Michael Howell of CrossBorder Capital in a Realvision interview earlier in November. As Howell characterizes the environment:

"If you look at the backdrop, I mean, this is one of the best backdrops I've seen in 30 years of being in the markets. It doesn't really get much better than this. There is lots and lots of cash around. But basically, investors are not particularly speculatively positioned yet."

In other words, with cash so easily accessible one would expect investors to have higher exposures to riskier assets like stocks than they do. As Howell puts it, "Equities are becoming a scarce asset, certainly relative to the huge amounts of liquidity." By one account, then, investors ought to be pouring into stocks.

Stocks look terrible

By another account, however, there has hardly been a worse time to invest in stocks. As John Hussman describes in his latest report:

"In nearly a century of data, including the market extremes of 1929 and 2000, this estimate [for 12-year nominal average annual total returns for a passive 60/30/10 mix] has never been lower than it is today."

He goes on to describe that the biggest drag on those return expectations is the equity component which is "more negative than at any prior point in history". Hussman's findings are also corroborated by Jeremy Grantham who is "presently advising a zero allocation to U.S. stocks here".

This rationale is also based on a comparison. Unlike Howell's comparison of equities to liquidity, however, Hussman compares equities to future cash flows:

"Even once a safe, effective vaccine is available, the very long-term stream of corporate cash flows will not suddenly jump above pre-pandemic highs. Yet valuations are already at the most extreme levels in history, even when we calculate valuations based on pre-pandemic fundamentals."

Compare and contrast

The contrast of these two entirely different perspectives on stocks provides some useful insight for investors. Since Hussman's comparison facilitates a quantification of expected returns, it is a more useful gauge for long-term investors. Since Howell's measure relies on transient liquidity conditions, it is more appropriate for short-term trading opportunities.

To this point, Howell is very clear in recognizing the potential pitfalls of his endorsement. It is entirely contingent on continued liquidity and the environment for liquidity is becoming increasingly fragile:

"Consequently, central banks have had to come in and they inject more liquidity to facilitate the rollovers, and that's the problem. It's going to get worse as we go forward. And the two paramount issues that are kind of on the horizon, which actually disturbs this whole debt liquidity access and makes it even more fragile."

Pathway to inflation

The continued availability of liquidity is not the only caveat. Liquidity has had a supercharged effect on asset prices because it has been stuck in the financial system. With no outlet to release the monetary pressure into the real economy, it has remained concentrated in financial assets. That appears to be changing, however.

By Howell's own admission, "the risk of inflation is going to pick up". One reason for that is simply because "the cost deflationary pressures of the last decade are now ebbing". China is no longer exporting deflation and supply chain costs are likely to rise as trade policy becomes more constrained. Another reason is monetary inflation because "central banks are basically trashing the value of money".

Monetary inflation is an issue Russell Napier has been highlighting most of the year and one he explores in depth in another recent Realvision interview. He emphasizes, "The most important thing for anybody watching this to know is that it's commercial banks who create money and not the central bank." To this point, he explains what changed his mind: "I finally began to grasp the scale and magnitude of the government guarantee programs for commercial bank debt."

This has certainly been impetus enough to spawn noticeable signs of inflation. Grocery prices are going up as are many commodities prices. House prices keep rising. There are plenty of examples. However, Napier also makes the point that inflation doesn't really become endemic until money supply is released into the wild of the real economy: "And the final point in inflation. It has to get the wages. If it doesn't get to wages, it doesn't work."

We are beginning to see signs of that too. A ballot measure to raise the minimum wage by 50% passed overwhelmingly in Florida which can hardly be considered a diehard blue state. Further, sentiment seems to be softening for higher minimum wages across the political spectrum as shown in the chart below.

Source: The Brookings Institution

Implications

How can investors apply these insights to better manage the risk of inflation? The answer is easier for longer time horizons. For those, all the foundations of a fundamentally different inflation environment are in place. As such, anyone with a reasonably long investment horizon should be hunting for inflation beneficiaries and accumulating opportunistically.

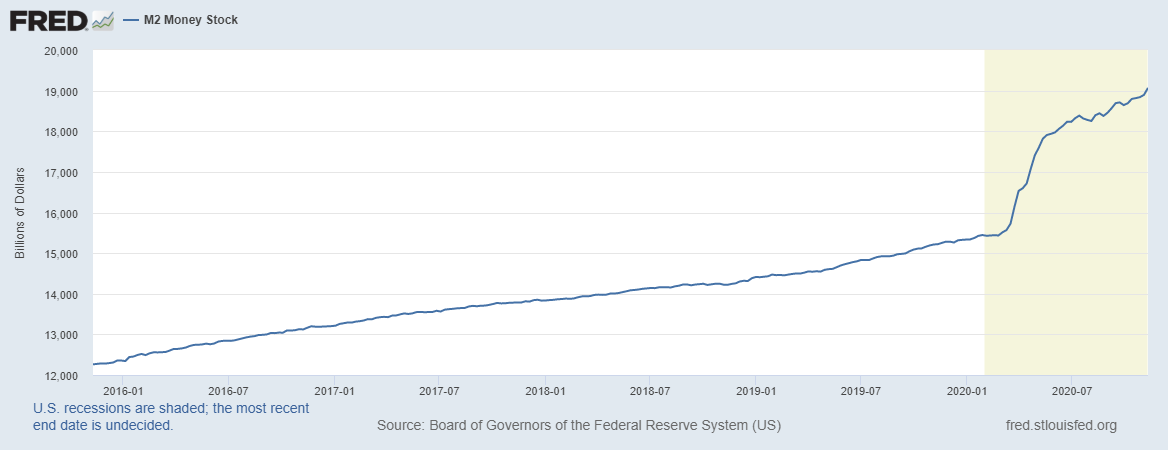

The short term is less clear. On one hand, there are certainly indications that inflationary pressure is beginning to emerge. Certainly, the massive increase in money supply provides a lot of dry kindling that can ignite with the slightest spark.

On the other hand, however, significant excess capacity and high unemployment suggest the roots of inflation do not yet run deep. In addition, much of the value destruction from lockdowns earlier in the year has not yet been recognized.

Further, although money supply has rocketed up this year, the drivers of continued growth have hit some snags recently. Total bank credit has continued to inch higher according to the latest Fed H.8 report (11/20/20), but loans and leases have declined from highs earlier in the summer. The recent announcement that the Treasury will allow some special lending facilities to expire at the end of the year at least temporarily dampens the monetary impulse. In sum, there is at least a fair chance of experiencing another deflationary episode.

As a result, short-term expectations for inflation appear to be leaping ahead of real sustained pressures. This creates a challenging calculation: Should investors leap to action now at the risk of overpaying for inflation hedges, or should they forestall such actions at the risk of paying even higher prices later?

The calculation is further complicated by a couple of distinct possibilities. One is that it may take the impetus of a severe crisis to compel an agreement for another round of fiscal and monetary stimulus large enough to seal the fate of inflation. In the event of such a severe crisis, however, there are no guarantees that policy responses will be big enough or effective enough to accomplish that. As a result, investors are left with a monster of all catch-22s.

One factor that is likely to tip the scales is the scope of future fiscal policy. With the firepower of monetary policy largely used up, greater reliance will be placed on the fiscal side. After an especially contentious election, however, and the likelihood that the Senate and House will be split, it is hard to imagine that negotiations will be smooth or that measures will be unusually generous. Insofar as that is the case, it will be a while longer before we experience systemic inflationary pressure.