Observations by David Robertson, 10/22/21

After looking very sluggish from the beginning of September, stocks started taking off late the prior week and have been on a tear since. Let’s take a look at what is going on.

By the way, I’m taking a break next week. I’ll be back on November 5th.

Let me know if you have comments. You can reach me at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

The most interesting aspect of the recent runup in stocks is how little there is behind it. Sure, people have talked about positive early earnings reports, good seasonality, the potential for high buyback volume, and other items, but there has been exceptionally little substantive explanation for the sudden change.

Also interestingly, the move got started with a huge 1.7% rip in the S&P 500 on 14th. Almost nothing was mentioned of it in financial news. One thing that was going on was a massive decline in volatility. Vix dropped from almost 26 on Sept 20 to 18.64 on Oct 13. It got pounded down to 16.86 on the 14th and has continued down to the mid-15 range – among the lowest levels of the year.

The nosedive by Vix is especially interesting in contrast to the spike in the bond volatility index, MOVE. As The Market Ear ($) reports (Oct 19 2021 at 11:50), “The gap between MOVE and VIX is huge. The ratio (chart 2) is now at the highest levels since Corona hit the world.”

We know the Fed’s purchases of mortgage-backed securities settle in the middle of the month so that typically provides a boost to stocks, but the pop has lasted longer than that. It is possible stocks are merely returning to their trajectory prior to the September setback. It’s possible the pop was just due to a buy-the-dip reflex. Regardless, with interest rates continuing to press higher, the exuberance of stocks leaves the impression of going out for a joyride while completely oblivious to the dangers that lurk.

Housing

Most people are familiar with some form of the graph above that depicts huge increases in home prices over the last year. As the lower part of the graph shows, no other period in the last twenty years has experienced home price appreciation at the rate of last year. As the lower part of the graph also shows, the last time home prices jumped anything like they did last year, which was in the mid-2000s, the result was a multi-year housing crisis. As it turns out, this unfortunate outcome is also a fairly mechanical one …

Zombie Banks, Crypto & MSRs

“The credit of the borrower probably has not changed, but the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio of the house has fallen 10-15 points thanks to Chairman Jay Powell and his pals on the FOMC. Today, the new conventional loan looks great. But in a couple of years, when home prices correct down to the floor of this credit cycle – say ~ 2019 prices – then the true credit characteristics of the asset will surge back into view. The conventional MBS issued by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac will start to evidence default and loss rate characteristics normally found in a Ginnie Mae MBS. This is called ‘credit migration’.”

The problem materializes not because of anything anyone does or doesn’t do, but simply because conditions change. When mortgage rates plumb all-time lows it helps drive house prices up, and that makes everyone’s credit look great. When rates start rising again and home prices come down, all of a sudden, many mortgages will suffer increasing loan-to-value ratios (because values decline) and become much weaker credits. The interesting thing is this pattern is completely foreseeable; it just takes some time. It is coming.

Energy

Inflation drives up drillers’ costs in US shale oil patch ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/464bc3a6-d162-4f94-9180-edc7043516ab

“The capital may be there due to higher oil prices, but the people, the labour, the inventory . . . the equipment, drilling rigs, the frack equipment, it just is not there,” he said in an interview in early October. “So that’s going to be a problem if the world needs us in 2023 to ’25.”

The quote above is from Scott Sheffield, the CEO of Pioneer Natural Resources and one of the more prominent voices in the industry. His point is a good one: Supply shortages are not just about short-term prices. It takes more than just some short-term price adjustments to alleviate those shortages. It takes visibility into longer-term returns for money to be invested into capital equipment and it takes visibility into attractive careers to attract people.

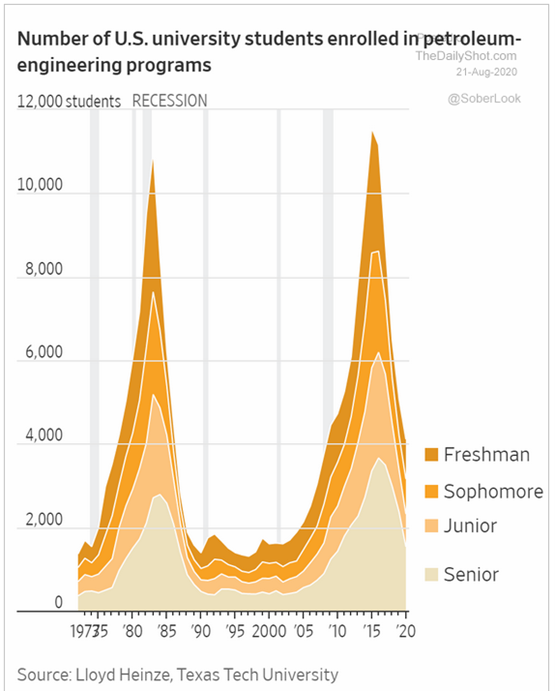

One quick and easy proxy for employment visibility is university enrollment for professional jobs. After all, paying for a university education is also a long-term investment at least ostensibly seeking adequate returns. I originally showed the graph above in Observations from 8/21/20 and it is just as useful today. This is why commodity prices cycles tend to be longer-term – because supply adjustments can only happen in meaningful quantity based on longer-term return potential.

Economy

One of the ongoing narratives about the economy is that people have so much money saved up, there is “pent-up” demand to spend it. This story line is corroborated in part by the fact that spending on goods has been higher than spending on services (which haven’t been as available).

This view is summed up neatly by Robert Armstrong in the FT ($):

“At Bank of America, credit and debit card spending rose 21 per cent, at JPMorgan it was up 26 per cent, and spending on Citigroup cards rose 20 per cent. Whatever else is going on in the global economy, the US consumer is feeling flush (why else would so many of them feel able to quit their jobs)?”

The graph above suggests a more nuanced story line. As consumer confidence has deteriorated and consumer finances have deteriorated considerably relative to pre-Covid, it a clear a significant subset of the population not only doesn’t have wildly inflated savings but are experiencing a deterioration of financial conditions at a rate comparable to that of the lowest depths of the lockdowns.

It's not hard to see the pent-up demand narrative as missing something important. A lot of people are struggling with higher food and energy prices. Further, a lot of people have not experienced any of the benefits of massively rising home or stock prices. In addition, the flareup of the Delta variant has delayed recovery in many areas. Also, the recent expiry of pandemic benefits and rent and mortgage moratoriums suggest there will be a period of “digestion” before we reach anything like steady-state economic activity.

One implication is there are no simple narratives that adequately describe the multiple crosscurrents in the economy right now. Another implication is there will continue to be political tension as long as different segments of the population have wildly different economic experiences.

China

Home is Where the Hurt is, Almost Daily Grant’s, Thursday, October 14, 2021

https://www.grantspub.com/resources/commentary.cfm

“Beijing, which arguably helped usher in the current tumult by rolling out the so-called three red lines policies limiting balance sheet growth, appears content to let the situation play out rather than ride to the rescue. ‘The industry is in a period of survival of the fittest and does not require excessive administrative intervention,’ Kuang Weida, director of the Center for Urban and Real Estate Research at Renmin University of China, tells Yicai Global.”

“More broadly, the starring role of real estate in China’s economic miracle (pegged at between 23% and 30% of GDP by various observers) begs the question of what consequences may follow an early autumn freeze. Contracted sales among China’s 100 largest developers plunged by 36% year-over-year in September, one of the most important selling months of the year, according to data provider CRIC. With activity on the fritz, highly leveraged industry players are obliged [sic] cut prices to generate the necessary revenues to service their debts.”

One of the defining characteristics of the market mentality in general, and in regard to China specifically, is the alertness to acute crisis but complacency regarding chronic problems. The pro-China argument now goes, “Evergrande is not going to blow up the world like Lehman Brothers did so … no worries … carry on.” A key assumption is that China’s autocratic state will be able keep everything under control. This sounds suspiciously like believing “subprime is contained” in the early days of the financial crisis.

The real question about China for investors ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/8cf5c7a6-d7c2-4c8a-8c47-51236e20ee75

“Combating contagion from the woes of Evergrande and other property developers spreading into the broader economy requires an effective countercyclical policy response. But that response has not been forthcoming so far and the reasons for Beijing’s inaction are unclear. Are China’s technocrats holding back because the current property market turmoil is part of a controlled effort to reduce risk? Or have new political factors prevented China’s technocrats from acting?”

“But the credibility of this expectation depends upon the policymaking process working as it has in the past. At some point, waiting too long to respond to the current property market turmoil will generate too much contagion and several factors will weaken China’s economy and financial system. They include the effects of falling property prices on household consumption, the impact of falling land sales on local government finances and the use of property as collateral for lending.”

Logan Wright goes beyond making easy assumptions about China by asking difficult questions. Is “Beijing’s inaction” by design or is it a function of serious political constraints? Good question. It is an appropriate situation to do so since the underlying conditions are different than in the past. Indeed, a long tail of consequences has the potential not just to create headwinds for a long time to come but to ripple into the global economy as well.

Inflation

When it comes to rising costs, companies normally see the warning signs before consumers do. If the cost increases are isolated or idiosyncratic, companies normally just manage around them. This happens all the time. When cost challenges are more persistent, companies need to resort to making the tradeoffs between raising prices (and reducing demand) and keeping prices relatively constant (but suffering lower margins). Regardless, it is clear a significant portion of companies are now seeing cost pressure and will need to start making those decisions.

Commodities

Commodities have been a hot topic and are reflective of one of the bigger challenges for investors today. Longer-term, commodities tend to go through cycles that can complement stocks. When commodities are cheap, stocks tend to do well. When commodities do better (to justify investment in additional capacity), stocks tend to be weaker. As a result, in general, and over longer periods of time, commodities are good inflation hedges.

A couple of factors are throwing a wrench into that logic short-term, however. First, as the graph shows, the value of commodities as a diversifier is largely related to the US dollar. When the dollar declines in value, as it tends to do under inflation, commodities normally provide a useful offset. The only problem is the dollar index has been strong at the same time commodities are going up. Either the relationship has been broken (at least temporarily) or the US dollar index is not reflecting inflation, at least relative to other currencies.

A second complicating factor is the run up in commodities is also not obeying its usual countercyclical relationship with stocks. Rather, both are going up. In the short-term, this can be partly explained by speculative fervor. With lots of money around, it is chasing whatever story it can – and commodities is one, as is stocks.

All of this makes the proposition of buying commodities as a longer-term inflation hedge and as a hedge against stocks that much harder. In the short-term, commodities are acting as more of a “risk-on” asset which makes them extremely vulnerable to valuation overshoot and to “risk-off” sentiments. Selectivity and timing will be key.

Monetary policy

The sequencing trap that risks stagflation 2.0 ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/99eacd37-a2e0-4c74-b6de-99c1ca7caa70

“This has lured them [the Fed] into a ‘sequencing trap’ — responding to surprises, such as inflation, first through a tapering of asset purchases and then by raising the benchmark policy interest rate in baby steps. Yet aggregate demand is likely to be far less sensitive to central bank balance sheet adjustments than to the real cost of money, and monetary policy actions have a long lag time. This is particularly worrisome for the Fed, which has embraced a new ‘average inflation targeting’ approach designed to delay policy responses to compensate for earlier undershoots of inflation.”

“The bigger surprise has come from the demand side. Few guessed the global economy would snap back from the Covid-induced lockdowns with such extraordinary vigour. As economies now slow from their rapid recoveries, that will leave the level of aggregate demand uncomfortably high relative to an impaired supply side. To me, that spells an enduring inflation problem.”

If you wanted to script a situation in which policymakers didn’t even have a fair chance to get thing right, it might go something like this. You would start by suddenly and dramatically cutting off demand. Then, rather than allowing demand to return naturally, you would supercharge it so supply chains would bust in predictable and unpredictable ways. Then, as the pig of demand was passing through the python of supply, you would add one final gimmick: You would further constrain policymakers by deferring any policy changes for a year so.

That combination of factors would make it almost impossible to get policy right, even if the diagnosis and ideas were exactly right. Indeed, this is exactly the situation the Fed is in. One of the most pernicious and least appreciated challenges of monetary policy is the inherent lag from implementation to realized results. It appears, however, this natural difficulty is not enough; the Fed is adding another degree of difficulty by delaying policy responses through “average inflation targeting”. Hold my beer.

Investment landscape

Resistance to Buying Stocks Is Becoming Evermore Futile ($)

“What is strange about this, and disconcerting, is that the optimism is reaching these peaks in a situation where confidence in growth has declined, and fears of rising inflation and rates are back. Bonds indeed don’t look like a buy — but a lot is being built on the notion that they leave us no alternative but to buy something more risky.”

John Authers sums up the situation well. The current conditions of slowing growth, rising rates, political dysfunction, imminent tapering, and another debt ceiling showdown on deck for the holidays, is not what one would normally script for record high allocations to risky stocks.

Perhaps, we are too judgmental in calling stocks risky? Michael Howell explained, “investors want long duration safe assets,” on the Allocation panel at the Global Independent Research Conference on Oct 13. Then, he went on to describe the S&P 500 as the quintessential long duration safe asset. Long duration, yes, but safe?

In the world of large allocators who pretty much do need to decide between stocks and bonds due to their size, it is not impossible to view stocks as safer than bonds in an environment of inflation. At least stocks have a fighting chance to offset higher costs by raising prices. Bondholders have little recourse but to sit and watch purchasing power erode. If one also assumes that central banks can, and will, act to prevent large nominal losses in stocks and bonds (due to their role in providing valuable collateral for financing), the extreme allocation to stocks becomes more understandable.

I have a hard time getting to this point myself, but we have to consider the possibility. The relevant questions are: “How far will the Fed go to preserve nominal asset values?”, and, “How far can the Fed go to preserve asset values?”.

Implications for investment strategy

The Wealth Is In The Denominator

https://www.hussmanfunds.com/comment/mc211015/

“The problem here is that a) the expected return of the S&P 500; b) the probability that stock returns will exceed Treasury bill returns and; c) the likely depth of cyclical market losses, are all heavily dependent on the level of starting valuations.”

John Hussman provides an excellent reminder of the pitfalls of creating quick and easy investment plans. Many financial planners, investment advisors, and individual investors simply plug in long-term average returns for each asset class as a basis for planning. The fact of the matter, however, is any single investor’s experience is unique and is very significantly shaped by starting conditions. Without considering starting valuations, one is apt to have a very different experience than what “long-term averages” suggest.

“Easier and easier money, bigger and bigger deficits – that’s the destiny, until – and this is the big risk. A deflationary slowdown is easy for policy makers. They’ll print more money and spend more money. What’s hard is when they’re constrained, and that constraint is obviously inflation and currency, and that’s where the gig will be up. That’s actually what, in our view, everybody has to start hedging in their portfolios – it’s not the next disinflationary or deflationary downturn. It’s essentially inflation and currency problems becoming constraints on the government and this world where we’ve been living in where policy makers can get whatever they want from the stock market and interest rates to one where they can’t.”

This second quote comes from Greg Jensen at Bridgewater Associates. He goes a long way in answering both of the questions from the “Investment landscape” section: The Fed will protect asset values as long as it can, and it can protect them until inflation gets traction and “the gig is up”. As a result, inflation protection is the main investment job right now.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.