Observations by David Robertson, 10/25/24

With a week off and an election coming up, there is a lot of news to sort through. Let’s jump right in.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

The biggest news of the last few weeks has been the big rise in 10-year Treasury yields. After hitting a low of 3.62% in mid September, they have risen fairly steadily to 4.24% as of Thursday morning. This is important because longer-term rates are more representative of financial conditions for many forms of borrowing, like home mortgages, than short-term rates. In other words, conditions are getting tighter for many borrowers now.

The outstanding question is what the longer-term implication of the rate increase will be. To be sure, moves in longer-term rates are especially subject to narratives on both the way up and the way down. On the way down, the dominant narrative was US economic weakness. Therefore, much of the rise from the bottom has simply been a reversal of that narrative as fresh economic data has disproved the thesis.

A new narrative is forming, however, that supports significant further increases in the 10-year yield. As the story goes, fiscal deficits are on an upward trajectory regardless of who wins the election. With that being the case, inflation is likely to become a progressively bigger problem that will require higher yields for bond investors. While I believe there is more room to run on the upside, I also acknowledge there is also a deflationary risk from China that could reverse the narrative some time in the next few months. Either way, it will be good to review the Treasury’s Quarterly Refunding Announcement next week for clues about upcoming supply.

As the S&P 500 has been bouncing around the last couple of weeks with little direction, meme stocks and other speculative investments have taken over as market leaders. The chart below from The Daily Shot illustrates the comparison.

For all the chasing of stocks, one group is prominently inactive: insiders. The chart below from Jason Goepfert (h/t Jesse Felder) shows insider purchases at their lowest level in 13 years. Not exactly a ringing endorsement.

Credit

A good thread from Bob Elliott highlights both the pros and the cons of bank credit:

US banks are doing pretty good, even those regional ones everyone was so worried about. But most banks have remained reticent to extend credit. With banks' conditions improving & the economy doing well, banks are well positioned to lend as demand for credit picks up.

The big worry about CRE is moving extremely slowly as expected, with charge offs flattening out in recent quarters at ~30bps, which is nothing compared to the 300-500bps of NIM earned on many of these loans.

On one hand, the risk of bad commercial real estate (CRE) loans has remained quite manageable as the costs have been easily covered by net income. On the other hand, banks have remained cautious on expanding their balance sheets, thereby limiting credit growth.

If the reason for that caution is an expectation of worsening credit and/or bad debt expenses, then the caution is a warning sign. However, it may very well be that the caution is a prudent pause before liquifying the economy with rising credit.

As a result, the relative stasis of the banks can be interpreted in vastly different ways. Unfortunately for investors, this is one more element that just adds to the level of uncertainty.

China

China’s property crisis claims more victims: companies ($)

So whose homes are being repossessed? In China the main holders of properties subject to foreclosure are not households but companies. Just like average punters, firms in China often struggle to find good investments and therefore plough cash into commercial and residential property.

This is a little public service announcement from the Economist informing investors that China’s housing crisis is not confined to just households. Unlike in the US, “rich Chinese often have had few investment options other than apartments”. That includes business owners. With foreclosed properties reaching nearly 800,000 in 2023, it’s a nontrivial task to figure out where the pain is being felt.

This reality also provides important context for the package of public policy measures released in recent weeks. To the extent businesses are every bit as vulnerable as households to the foreclosure crisis, it’s important for officials to establish some kind of floor on asset prices in order to prevent a wider deflationary spiral. As a result, efforts to prop up asset prices should be seen less as a big bazooka to turn things around and more as an emergency tourniquet to stanch a life-threatening loss of blood.

Investment advisory landscape

One of the ongoing trends in the advisory landscape is the proliferation of exchange traded funds (ETFs) at the expense of other formats such as mutual funds. While this makes sense on many levels, it just wouldn’t be Wall Street if a good idea wasn’t pushed way too far. If the leveraged and doubled leveraged and triple leveraged ETFs weren’t enough of an indication of an inflection point before, now we have even more evidence.

Exhibit A is a group of ETFs recently rolled out by Battleshares and noted by Ptuomov on X. The sole purpose of these ETFs is to reflect specific pairs trades and to leverage both sides of the trade. These types of trades are frequently used by hedge funds in order to generate a high reward/risk trade. These ETFs allow traders to participate in similar trades at home but without the same dynamic monitoring, risk management, and leverage calibration the pros use. Wheeeee!

Exhibit B is presented by the FT ($) which highlights efforts by large investment firms to bring private strategies like private credit, private equity, and venture capital to public markets by way of ETF vehicles. Bob Elliott highlights the obvious shortcomings of such ventures: “The trouble with trying to mimic PE & VC in an ETF is there is little value in creating another high vol equity exposure …” As a result, it’s pretty clear the primary motivation in such efforts is to provide a roadmap to higher fees for the sponsors and not any substantive utility for investors. Same ole, same ole.

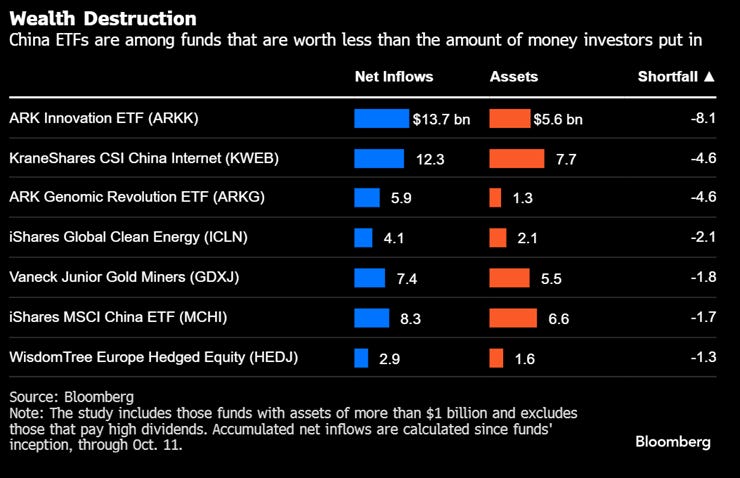

Finally, the chart below from Brent Donnelly shows a league table of ETFs that have destroyed the most investor wealth. One lesson from the chart is that it is a mistake to believe that just because an ETF exists, that it has a good reason to exist. This isn’t true. Investment firms spawn new products like dandelion seeds in a summer breeze.

Another lesson is that in order for an ETF to lose a lot of money, it needs to have attracted a lot of money to start with. As a result, it is often the splashiest, sexiest funds that cause the most harm — because so many people pile into them.

Investment landscape I

Subsets and Sensibility

https://www.hussmanfunds.com/comment/mc241017/

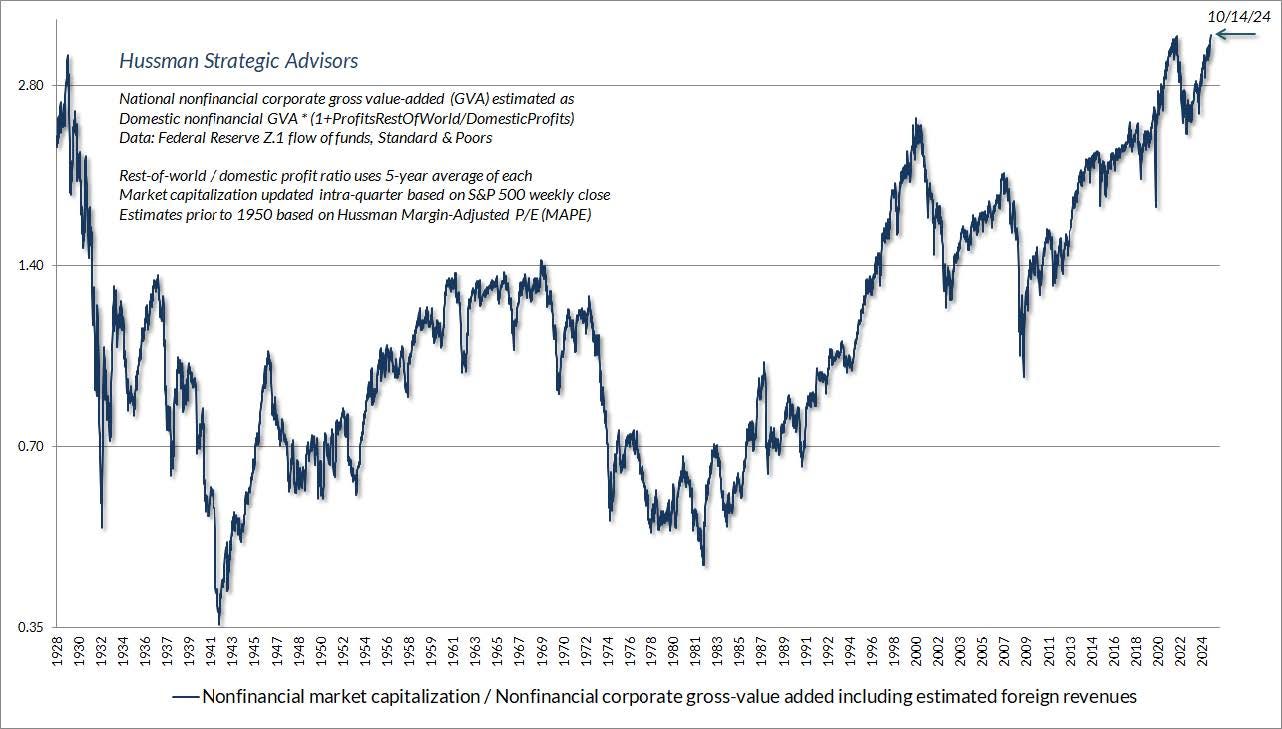

On October 14, 2024, the U.S. equity market reached the most extreme level of valuation in history, based on the measures we find best-correlated with actual, subsequent 10-12 year returns across a century of market cycles … The recent level of 3.40 exceeds every previous extreme, including 1929, 2000 and 2022 … The chart below shows our estimate of the 12-year “equity risk premium” of the S&P 500, defined as the expected 12-year average annual total return of the S&P 500 over and above Treasury bond returns. The current estimate is -9.9% annually.

Since its previous high on July 16, the S&P 500 has outperformed Treasury bills by just 1.6%, but the fear-of-missing-out among investors seems nearly frantic. One can’t share any sort of historical evidence suggesting potential market risk without a barrage of replies ranging from disdain, to long-debunked arguments, to plain apathy – “nothing matters.” This is a sure sign that unconditional thinking and passive, price-insensitive investment dogma has taken hold of investors.

I don’t like to belabor the issue of valuation because beyond a certain threshold it becomes counter productive. People just turn off. Nonetheless, valuation remains a massive issue for long-term investors and therefore deserves a regular, if judicious, update.

John Hussman provides exactly this with his latest commentary. The glaring finding is that “the expected 12-year average annual total return of the S&P 500 over and above Treasury bond returns. The current estimate is -9.9% annually.” You read that right. Stocks are currently the most overvalued in history.

Further, as John Authers ($) reports, David Kostin, the chief US equity strategist at Goldman Sachs, is “suggesting that the [S&P 500] index will gain only 3% in nominal terms (1% in real terms) per year over the next decade — which would be one of the worst on record.” So, the prospect of very poor equity returns is becoming more widely appreciated.

This presents some good news and some bad news. The bad news, as the Kobeissi Letter points out, is “US households now hold 48% of their assets in equities, the highest since the 2000 Dot-Com bubble peak.” This will cause a lot of pain.

The good news is it doesn’t take special training in rocket science to do well with stocks. As Ben Graham famously advised and Jason Zweig recently posted, “The genuine investor in common stocks does not need a great equipment of brains and knowledge, but he does need some unusual qualities of character.”

In practice, this means it is far more important to be able to resist the temptation to overreact when times are good or bad than to be extremely facile with financial terminology or Excel workbooks with dozens of sheets. So, while it is never fun to be out of a game that everyone else seems to be getting rich by playing, ultimately that is exactly how you avoid the biggest losses.

Investment landscape II

Control Theory -- or "Proof of a System Is What It Does" (POSIWID) ($)

https://www.yesigiveafig.com/p/control-theory-or-proof-of-a-system

Since the advent of the Fed dual mandate in 1977, the tradeoff between corporate profits and labor share in the economy has been decisively skewed in favor of capital as the Fed raises interest rates in response to a hot economy defined by wages and unemployment while ignoring income gains by capital.

I also want to emphasize that Fed policy is not the sole driver of the change in corporate profit share — “globalization” via poorly negotiated free-trade agreements that mobilized capital to seek out the lowest-cost labor resources certainly played an important role. As did the Bork Doctrine, which eliminated most forms of anti-trust enforcement and created modern monopolies based on intellectual property rather than large-scale factory investments, clearly played a role as well.

Work hard, study, try to be a good person — and you get ahead, right? Right? Something like this is the heart of the social contract many people operate under, but for many years has just not been a reliable formula for success. Indeed, this disconnect seems to be the root of a great deal of dissatisfaction with the political and economic environment.

In his Substack piece, Mike Green reveals some of the causes of a broken social contract. For starters, since the Fed was issued its dual mandate, there has been a systemic bias in favor of capital over labor. Debate the details all you want, but as Green highlights, the proof a system is what it does — and what the Fed does is boost corporate profits at the expense of the share of labor’s rewards in the economy. Jay Powell regularly pledges his commitment to serve the people of the United States, but his actions speak otherwise.

Of course, other factors are also at work and Green does a good job of highlighting the most meaningful ones. A lopsided and unfair approach to globalization and the significant elimination of antitrust enforcement have also been important contributors.

To the extent that these are root causes of political and economic dissatisfaction, we have a good starting point for corrective public policy. That’s helpful. Further, these issues provide good markers from which to monitor the progress of the tug-of-war between capital and labor going forward. However, don’t expect conditions to get meaningfully better for workers until we see improvements in the Fed’s support of capital at the expense of labor, the unfair approach to globalization, and/or antitrust enforcement.

Investment landscape III

One of the interesting observations of the investment landscape is the increasing array of volatility indexes that are rising sharply. The MOVE index of fixed income volatility has probably been the most noticeable, rising from “90 to 129 in less than a month” (themarketear.com ($)).

Another example from themarketear.com ($) shows volatility in the yuan has spiked: “The moves in the Yuan have not been overly spectacular, but Yuan volatility has exploded to the upside, and stays at these new elevated levels. Looks like Yuan volatility is pricing something more ‘serious’ for the Yuan...”

It can also be argued the runup in gold this year is an indication of rising volatility. As Mohamed El-Erian writes in the FT ($), “Gold’s ‘all-weather’ characteristic signals something that goes beyond economics, politics and higher-frequency geopolitical developments.” In other words, gold can capture large-scale developments that other more narrowly focused markets can miss.

In sum, volatility has always been an important indicator of stress in markets. Over time, however, the information content of a number of volatility indicators has been eroded and that has created a false sense of security. While recent flairs of volatility are undoubtedly being influenced by the upcoming election, investors would do well to listen carefully to the signal being sent.

Investment landscape IV

Why have markets grown more captivated by data releases? ($)

News has always driven markets, but curiously the importance of big data releases has grown substantially in recent years. Analysis by The Economist finds that, over the past year, bond-market moves in America have been twice as large on days with major data releases or Federal Reserve decisions as on other days, while equity-market moves have been two-thirds larger (see chart). In both cases, these were substantially above the historical norm.

This piece by the Economist highlights an important change in the investment landscape over the last several years. The finding that “the importance of big data releases has grown substantially in recent years” certainly comports with my experience, at least in regard to the magnitude of market reaction to such releases.

That said, the author’s interpretation that “markets [have] decided to take hard facts much more seriously” despite the fact that “the quality of statistics has started to fall” seems almost hopelessly naive and completely misses the bigger issue.

Namely, the vast majority of market activity is NOT about taking data seriously. If it were, we probably would not be at all-time high valuations for stocks. Rather, a good chunk of market action, especially around data releases, is the result of bets made on specific outcomes. It is the result of markets becoming casinos. In that respect, betting on CPI to come in at 0.2% is no different than betting on Lamar Jackson to have three or more touchdowns in the next game.

Indeed, it has become extremely difficult to take data releases seriously as the Economist suggests. For one, the data are constantly adjusted and revised to the point where they have little meaning at the time of release. For another, alternative data often provide more timely and accurate insights. And, as Brent Donnelly mentions, policymakers mix and match data to suit the purposes of the narrative they are telling: “We hang on every new indicator they [policymakers] claim is important. Then they just pick some new ones. It’s fun.”

So, the big point that the Economist completely missed is that data can serve two general purposes: It can serve to inform decision making or it can serve to substantiate an ulterior motive. As market prices have become increasingly disconnected from economic reality, data releases have evolved into betting events that distract attention away from underlying economic trends. Long-term investors would do well to focus more on the latter and let others be “captivated” by the flashing lights of the casino.

Implications

There are basically two ways to look at markets right now. One is to acknowledge some instances of rising volatility but to attribute them primarily to regularly recurring patterns such as normal pre-election antics. With the S&P 500 hovering near all-time highs, spots of volatility can be seen as fairly benign. The implication is to stick with stocks.

Another very different view is that while the election is nudging volatility higher, there are also much deeper changes taking place. Mohamed El-Erian ($) describes, “What is at stake here is not just the erosion of the dollar’s dominant role but also a gradual change in the operation of the global system.” He goes on:

As it develops deeper roots, this risks materially fragmenting the global system and eroding the international influence of the dollar and the US financial system. That would have an impact on the US’s ability to inform and influence outcomes, and undermine its national security.

In short, we are experiencing something like a phase change in the global monetary system — and that is a very big deal. The implication is to hunker down and focus on preserving wealth as a primary objective.

Of course, each investor gets to choose his/her own adventure. I am convinced a much bigger game is at stake here; this is not just more of the same. Therefore my preference lands firmly in the latter camp.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.