Observations by David Robertson, 10/4/24

The week included Iranian missile strikes, more Chinese monetary easing, the end of the quarter, and even more political gibberish with the VP debate, and the start of a port strike. Let’s try to get it all in perspective.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

The star of the show for the last couple weeks has been Chinese stocks. One of the more potent representations, the China internet stocks ETF, KWEB, was up 50% from September 16th through Wednesday’s close. Apparently, traders responded to China’s various policy modifications with the playbook, “ready, shoot, aim”!

On Thursday, KWEB reversed course by dropping 4% right at the open. We’ll just have to wait and see if the spike marks a premature and overzealous market response, or if it indicates a healthy breather on the way to bigger and better things.

Tuesday was an interesting day in the market as weak manufacturing surveys were received as indications of imminent recession. Most notably, the 10-year Treasury yield fell about 10 bps. This is especially interesting since 10 bps is a big move and the surveys are not especially good economic indicators. By Wednesday morning, yields were back above where they ended on Monday.

Meanwhile, floating around in the background has been a slew of antitrust cases. This post from zerohedge provides some perspective: “43% of S&P 500 market cap now under FTC/DoJ antitrust investigation: BofA (NVDA, AMZN, META, GOOG, TSLA, JPM, UNH, V, MA, WMT, KO, PEP, ADBE, etc).”

So, a case here and a case there and pretty soon you are talking about potentially a huge impact on the S&P 500 and broader markets! These are not just a few isolated cases any more.

As such, not only is there potential for a number of common business practices to get screened out as being anticompetitive, but there is potential for a completely new, and different, narrative to form around big tech and other large companies. Maybe they didn’t become so dominant exclusively from innovativeness and aggressive experimentation. Maybe relentlessly anticompetitive practices played a role. We’re about to find out.

Finally, geopolitics is back on the radar as Iran struck back at Israel with a shower of missiles. I won’t say much about this except to remind investors that a large number of simmering conflicts in a politically and economically fraught environment creates a lot of potential for things to boil over.

Economy

While the narrative of an economy that is just barely staying out of recession continues to hold sway, disconfirming evidence is accumulating. For one, gross domestic income for the first and second quarter was revised significantly higher. Eric Wallerstein posts:

Real GDI +3.4% in Q2, revised up from 1.3%

Real GDI +3% in Q1, revised up from 1.3%

Leading contributor to upward revision was compensation. Recessionistas, what's the next move?

In addition, wage data derived from actual withholding taxes suggests wages have been growing solidly. Bill@wabuffo posts: “As I keep pointing out -- employment tax receipts DO NOT LIE.... And because compensation was underestimated, the personal savings rate was underestimated too...”

Sure enough, the ADP report on Wednesday morning showed an increase in jobs and a solid increase in wages at 4.7% and that was confirmed by a greater than expected increase of 254,000 nonfarm payrolls on Friday. As a result, it is hard to conclude that workers as a whole are enduring great hardship. Rather, the more plausible explanation is that market expectations for economic growth have gotten far too negative.

China

After China’s bit stimulus announcements the prior week, more news continued to flow out this week. Veteran China watchers have been busy trying to put it all into context.

Adam Tooze ($) saw the developments as being positive:

This question [of whether authorities would exceed expectations for stimulus] was answered decisively at the highest level on Thursday, with the monthly Politburo meeting for September issuing a clear call for additional stimulus.

The first signal was the urgency for more strongly countercyclical fiscal policy.

Other focused less on the “signal” and more on the details and commitment - which were lacking. Bob Elliott came away with a less optimistic view:

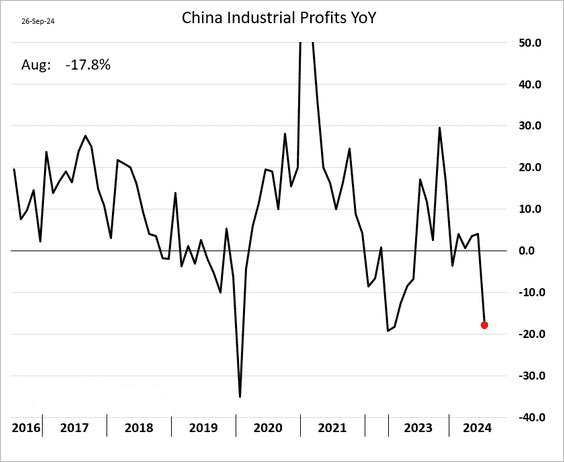

Chinese data overnight covering the pre-announcement period highlight the challenging task ahead. While policymakers have achieved a pop in equity markets, the measures still look insufficient to turn the underlying macro reality. Thread.

George Magnus saw a degree of desperation in the moves which left him skeptical:

China's leaders are spooked. They've managed to get stocks to rise by the biggest weekly amount in 15 years, but can their new strategies restore confidence , consumption and economic growth? Don't be so sure.

Michael Kao is also skeptical and explained why:

Musings of the Day, 9/27/24: This, more than the travails of the Chinese Consumer, is what concerns Xi the most imho, because to stay in power, China’s Runaway Assembly Line CANNOT STOP. This is why Export Competitiveness matters to China despite their Trade Surplus.

As he explains in a Substack post ($):

I still think the PBOC needs to significantly Devalue CNY at some point because the CCP's main concern is STAYING IN POWER, and to stay in power they need to keep people employed. To keep people employed, they can no longer push construction jobs given decades of Capital Misallocation to the Real Estate sector.

Like the Eye of Sauron, China’s Top-Down GDP Targeting has turned its unwavering attention from Real Estate to INDUSTRIAL CAPACITY — specifically Industrial Capacity …

Michael Pettis recognizes the consequences of faltering industrial profits also flow downstream and negatively impact the real estate sector:

SCMP: "A survey published in August showed that “unstable income” ranked as the top factor keeping homebuyers on the sidelines. About 43 per cent of respondents cited it as a “significant reason” for not buying a home."

Finally, Mohamed El-Erian highlights why the fundamental problem is so hard to solve:

The main policy challenge for China remains to revamp the growth model structurally. Absent that, reliance on stimulus would risk seeing the short-term benefits offset by further resource misallocations, larger pockets of over-indebtedness, and great risk aversion on the part of households.

This highlights two important issues. First, as the Economist ($) reports, the existing economic model is leading to “social stagnation” that creates a “potential political risk”:

Research led by two American scholars, Scott Rozelle and Martin Whyte, found that people in China once accepted glaring inequality, remaining optimistic that with hard work and ability they could still succeed. But the academics found they are now more likely to say that connections and growing up rich are the keys to success.

A second issue is that China’s policy challenges are also a microcosm of the global economy. Incremental liquidity provisions can still cause markets to jump, but they don’t transform economic growth models that are past their “use-by” date. Bags of money will not solve structural economic and political problems. New growth models are required - and that will be hard.

Japan

Japan elected a new prime minister last week and it is creating some international intrigue. First, it turned out to be a bit of a surprise that Shigeru Ishiba won despite Sanae Takaichi having a significant lead going into the first round. Second, as John Authers ($) explains, Ishiba “carved out a career as the ‘ani-Abe’, setting himself in opposition to the policies of the late Shinzo Abe, Japan’s dominant premier of the last few decades.”

One of those “anti-Abe” positions is being more of monetary hawk. However, there is also a question of how much political capital he will be able to wield. According to Taniguchi Tomohiko, “Ishiba’s policy positions and questionable management skills do not bode well [for a long tenure]”.

So, one question is, as Japan approaches a fork in the road, will they take it? Another question is, if Japan does pursue tighter monetary policy, how will an unwinding of the yen carry trade manifest? Good questions for all investors.

Monetary policy

How to measure liquidity ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/3c5cc389-a563-4413-ae83-8c7a0a6a1b97

Unhedged looks at liquidity conditions every couple of months, because we are convinced — at least in the abstract — by what we can loosely call the liquidity theory of markets: that when there is an increasing amount of cash around, investors try to get rid of the stuff, an attempt that pushes asset prices up.

One problem with analyzing liquidity is the concept keeps changing. For example, as John Hussman elaborates, the widely used measure of “M2” means something different after Quantitative Easing (QE) was implemented in the GFC than it did before: “Historically, ‘deposit creation’ was virtually identical to ‘loan creation.’ Growth in M2 was a reflection of intermediation. QE created a gap of excess reserves someone has to hold, now earning 4.9%.”

As M2 became less useful, market participants picked up on the concept of “Federal liquidity” which includes the “Treasuries and agency securities it [the Fed] has bought out of the market” and the bank term funding program. Subtracted from that total are the Fed’s Reverse Repo Program (RRP) and the Treasury General Account (TGA). For some time after Covid, this alternative measure of liquidity correlated well with stocks.

More recently, however, the correlation between Federal liquidity and stocks has broken down. As the FT’s Unhedged letter reports, “Federal liquidity is falling outright and the market continue to rise”.

One possible explanation for this breakdown is that Federal liquidity is too narrow a measure. Michael Howell of CrossBorder Capital espouses a global liquidity indicator which he updates on Substack ($). This has been turning up in recent months due to monetary easing by the Fed and the PBOC (People’s Bank of China) as well as rising asset (collateral) values and declining bond volatility.

Another possible reason for the breakdown is that it doesn’t capture the huge nonbank, i.e., shadow bank, part of the money supply. As Lee Adler highlights in his Liquidity Trader ($) newsletter, DVP repo usage has correlated well with stocks recently. It was flat to down in 2022 when stocks fell and it has been rising sharply since.

Perhaps the single best take on analyzing the liquidity environment is the conclusion of Robert Armstrong at the FT: “It’s hard”. There is no single measure of liquidity and the relationship between stocks and various forms of liquidity changes over time. This may be reason enough to question whether liquidity always provides a boost to stocks.

Public policy

Governments are bigger than ever. They are also more useless ($)

You may sense that governments are not as competent as they once were. Upon entering the White House in 2021, President Joe Biden promised to revitalise American infrastructure. In fact, spending on things like roads and rail has fallen. A flagship plan to expand access to fast broadband for rural Americans has so far helped precisely no one. Britain’s National Health Service soaks up ever more money, and provides ever worse care. Germany mothballed its last three nuclear plants last year, despite uncertain energy supplies. The country’s trains, once a source of national pride, are now often late.

The answer [to the question: if governments are so big, why are they so ineffective?] is that they have turned into what can be called “Lumbering Leviathans”. In recent decades governments have overseen an enormous expansion in spending on entitlements. Because there has not been a commensurate increase in taxes, redistribution is crowding out spending on other functions of government. This, in turn, is damaging the quality of public services and bureaucracies. The phenomenon may help explain why people across the rich world have such little faith in politicians. It may also help explain why economic growth across the rich world is weak by historical standards.

This article highlights some of the structural problems that cause widespread disappoint with government services. This creates an interesting paradox: At a time when more and more people look to government to solve big problems, government is becoming progressively less capable of doing so.

One of the big problems is the explosion of entitlements. Not only does spending on things like Social Security and Medicare crowd out spending on other projects (like improving public infrastructure, for example), but it also reveals a significant bias towards older people at the expense of younger people.

Nor are the problems likely to be resolved any time soon. As the Economist concludes: “Then again, Lumbering Leviathans are formidable. Interest groups are entrenched, familiar incentives apply and it is easier to live for the short term. The system has a life of its own.”

As a result, we end up with a government bureaucracy that most of the population doesn’t want. It’s big, inefficient, and redistributes income in a way that is massively unfair. And yet vested interests and inertia make it stubbornly difficult to change. No wonder so many people are not happy with it.

Politics

The Revolt of the Public, Part 2

https://www.mauldineconomics.com/frontlinethoughts/the-revolt-of-the-public-part-2

“Information has not grown incrementally over history but has expanded in great pulses or waves which sweep over the human landscape and leave little untouched. The invention of writing, for example, was one such wave. It led to a form of government dependent on a mandarin or priestly caste. The development of the alphabet was another: the republics of the classical world would have been unable to function without literate citizens. A third wave, the arrival of the printing press and moveable type, was probably the most disruptive of all. The Reformation, modern science, and the American and French Revolutions would scarcely have been possible without printed books and pamphlets. I was born in the waning years of the next wave, that of mass media—the industrial, I-talk-you-listen mode of information…”

“But the flip side of it [the massive increase in quantity of information], probably the more important side, which is the subtitle of the book, which is the Crisis of Authority of the Institutions. These institutions that basically had spoken from on high, we had accepted as authoritative. Suddenly everybody saw their mistakes, saw their self-centeredness, saw their condescension, didn't like either how competent they were or how self-interested they were. So the bond of trust was broken.

These quotes from Martin Gurri’s book, The Revolt of the Public, come from John Mauldin’s review of it. I find it interesting for two main reasons. One is that most of the focus on the impact of information proliferation that came with internet roll out was on all the useful and productive things that could be done with improved access to data. Little attention was placed on unintended consequences.

To that point, a second reason why I find the Gurri discussion interesting is because he shows how one of the unintended consequences of improved access to information manifested as a challenge to incumbent power structures. For example, he describes, “The public has access to information that it did not have 50 years ago, about matters ranging from police shootings to hurricane relief efforts to lurid details of celebrities’ sexual misconduct.” As a result, the internet provided, among other things, the ability for individuals to challenge, disprove, and humiliate figures from officialdom.

As individuals became empowered with greater access to information, they began usurping mainstream media as the primary source of investigative reporting and as voices speaking truth to power. Not surprisingly, people in positions of power did not take kindly to these changes:

He [Gurri] saw that the elites would be increasingly despised, as more of their mistakes and imperfections became exposed. He saw that the elites would respond to the public with defensiveness and contempt, but that this would only make the public more hostile and defiant toward authority. He saw that the public’s new-found power does not come with any worked-out program or plan, and as a result it poses the threat of nihilism.

This goes a long way in explaining some of the more confounding aspects of our political and investment landscape. For one, it has become progressively easier to see the faults of key decision makers. The massively increased ability to identify and publicize abuses of power has massively undermined the public’s confidence in authorities of all sorts. We see a lot more of the bad stuff.

It has also become much easier to see how widely divergent our leaders are from everyone else. Politicians are much older than average Americans and promote income redistribution policies that favor older people at the expense of younger people. Business leaders operate from playbooks with antiquated social mores and a belief that rules do not apply to them.

So, as the internet has exposed the masses to all of these shortcomings, it has also enabled people to wallow in them - and that has bred a great deal of unhappiness. The next step would be to harness the energy from that state of unhappiness into creative policy solutions. We are still a ways away from that though.

Investment landscape

I’m always a fan of simple explanations that capture the vast majority of an important phenomenon. Vincent Deluard accomplishes this beautifully with his recent market outlook:

If you just had one chart for the past 15 years, that would be it - the world's simplest hedge fund: LONG US / SHORT THE REST

But today we have

- Chinese stimulus

- 50 bp Fed cut at 3.2% core CPI

- the end of the Yen carry trade

Time for a reversal! The RoW will outperform

While the explanation is somewhat cryptic, the graph certainly highlights a key element: Not only have US stocks gone up over the last sixteen years, but they have gone up far faster than stocks from the rest of the world. This is the effect of the carry trade.

Now, imagine what that graph will look like when the carry trade unwinds/reverses. Non-US stocks will outperform and the graph will start turning down.

Implications

As most of the major central banks have launched their monetary easing campaigns, the big question for investors is how to invest in this sea of liquidity? Once again, Bob Elliott comes through with some great insights: “Such Over Easy policy has been pursued in the past by individual countries, but has never been run at a global scale.”

In addition to being run on a global scale, this “Over Easy” policy is happening in the midst of “pretty strong underlying global dynamics,” with stocks near all-time highs and credit spreads near all-time lows. As Elliott highlights, this “is very different than those past easing cycles.”

He concludes:

Such an environment of easy money favors "real" assets like gold, stocks and commodities, helps keep spreads tight, and is detrimental to duration as the economics of borrowing to invest in assets and the real economy look increasingly compelling.

I think this is a good framework to build from, but am hesitant to place too much weight on it now. For one, things may change after the election. Over Easy now may become Over Less Easy later. For another, while I believe Elliott’s baseline thinking is right, there is no small number of events which could rapidly undermine confidence. Finally, while the Over Easy monetary policy stance has a purpose in preserving stability through the election, it is not at all clear to me that a policy bias that favors capital over labor will be a vote-getter longer-term.

Elliott provides a useful blueprint to work from. It remains to be seen if it’s as good a blueprint for the several years as for the next couple of months.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.