Observations by David Robertson, 1/10/25

Whew, it’s already been a busy start to the year! I hope you got rested and recharged over the holidays because I think we’re going to need it! Let’s dig in.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

John Authers ($) captured a couple of phenomena that represent the unique flavor of financial markets heading into the new year. First, he chronicles a Wapo story that sent markets racing on Monday morning only to reverse hours later once the story was denied on social media by President-elect Trump:

At 6 a.m., the Washington Post published a story saying that the Trump team was “exploring tariff plans that would be applied to every country but only cover critical imports,” which it said would “pare back” what had been announced during the campaign. The dollar dropped sharply. A little more than three hours later, Trump’s riposte appeared on social media: “The story in the Washington Post, quoting so-called anonymous sources, which don’t exist, incorrectly states that my tariff policy will be pared back. That is wrong.” The dollar went back up

Perhaps “whipsaw” should be the word of the year?

On a separate subject, Authers graphically highlighted contributions to the MSCI World index by country. This is what it looks like:

No wonder US exceptionalism is such an easy theme to buy into!

Credit

As I highlighted in the Outlook edition last week, headwinds for credit will most likely pick up this year and it didn’t take long for confirming evidence to roll in.

Mohamed El-Erian posted about increasing default rates.

Per the @FT: “US companies are defaulting on junk loans at the fastest rate in four years, as they struggle to refinance a wave of cheap borrowing that followed the Covid pandemic.”

This is not about weak demand. Rather, it’s the consequence of excessive borrowing by companies, and risk taking by creditors, during what many thought at the time would be “QE infinity” with artificially low interest rates for as long as it mattered.

On a different front, Mike Green noted the increasing stress in student loans:

"we found that of the ~18 million consumers with a scheduled federal student loan payment of more than $0 as of October 2024, some 5 million consumers have not made any payments since the end of the pandemic-era federal student loan forbearance. Therefore, a significant number of consumers are at risk of having a delinquency reported to their credit files if they do not resume making their required payments."

https://www.fico.com/blogs/how-resumption-student-loan-delinquency-reporting-may-impact-fico-scores

In regard to the student loans, it’s hard to tell if the delinquencies are more a function of economic stress or simply an intentional form of resistance. Either way, whether through resumed payments or impaired credit, purchasing power will be reduced.

The same is true of the high yield market. Even though baseline economic conditions remain decent, the time has finally arrived when higher interest payments will be required from longer term loans through refinancing. This, of course, will reduce cash flows. This is also true more broadly across all credit markets that were able to term out debt for a period of time before the pandemic. In both cases, the costs are coming due.

China

China kicked off the year with news that it was reformulating its monetary policy. According to the FT, “The People’s Bank of China plans to cut interest rates this year as it makes a historic shift to a more orthodox monetary policy to bring it closer into line with the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank.”

In addition, the central bank “added that it would prioritise ‘the role of interest rate adjustments’ and move away from ‘quantitative objectives’ for loan growth in what would amount to a transformation of Chinese monetary policy.”

The news sent markets aflutter as people tried to interpret exactly what the statement meant. Michael Pettis is “skeptical that the PBoC's can manage this shift within the foreseeable future.” He added, “While it would certainly be a very important step in the long-term transformation and rebalancing of the Chinese economy, it would undermine supply-side growth in the near term.”

George Magnus shares the skepticism. He claims “The prob[lem] in China isn’t that credit is too dear” and that such a shift in monetary policy will only work “if there’s a big and still unlikely ch[ange] in fiscal expansion or income boost aimed at demand”.

There is no doubt the market interpreted PBOC’s statement as newsworthy; the yuan weakened abruptly the instant the news came out. Further, the yuan crossed the 7.30 threshold that had been viewed as a boundary. The chart below from The Daily Shot shows what clearly looks like a policy change.

The currency isn’t tottering just because of what the central bank said though; the economic situation is also worsening. The chart below from The Daily Shot shows private debt service ratios in China have hit a record high. No bueno. The room for Chinese officials to maneuver is diminishing rapidly.

As a result, the PBOC statement can be viewed several different ways. It probably is at least partly an indication of real change in monetary policy. There is also a good chance it is in part a message to the incoming Trump administration that it is proactively redefining its relationship with the US. Finally, it is also in part an indication that China’s financial and economic problems are reaching a critical state.

Geopolitics I

Xi has a plan for retaliating against Trump’s gamesmanship ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/ca79e423-7c0f-4883-a295-6fe1c73a2819

Beijing’s planned responses to Trump fall into three baskets: retaliation, adaptation and diversification. Mirroring US policies, Beijing in recent years has created a range of export controls, investment restrictions and regulatory investigations capable of hurting US companies. Beijing is unable to match tariff for tariff, so it will seek to impose costs in ways that inflict maximum pain. For China, failing to retaliate would signal weakness domestically and only encourage Trump.

In light of all the effort placed in trying to guess Trump’s policies, this piece by Evan Medeiros, professor at Georgetown University, senior adviser with The Asia Group, and former staff member of the US National Security Council, provides some fresh perspective. Not surprisingly, the perspective from the Chinese side is considerably different.

Medeiros notes, “Xi plans not only to respond, but to take advantage of Trump’s moves”. He continues, “Beijing believes it now understands Trump’s gamesmanship and can manipulate his administration.” Finally, he explains, “He [Xi] won’t personally embrace Trump and will retaliate early and hard in order to generate leverage.”

This analysis paints Trump as a nearly perfect opponent for Xi and China. All of the flaws that endear Trump to his followers, his impulsiveness and his aversion to strategic thinking, for example, also make him eminently manipulable.

However, just as Trump’s ability to dictate geopolitical relationships is often overstated, so too is Xi’s ability to control the geopolitical landscape. The truth is likely somewhere in the middle — which also makes the environment a lot dicier. Medeiros concludes:

Much could go wrong. Beijing’s confidence is matched by that of the Trump team. Both sides believe they possess the upper hand, can impose more costs and withstand more pain. The stage is set for a complicated, destabilising dynamic which, at best, results in a ceasefire.

Monetary policy

The really big story in the new year is the continuing rise of long-term interest rates despite the decline in short-term rates. While lower short-term rates provide some modest incremental relief to borrowers, higher long-term rates pose a greater threat to the economy because large chunks of the economy, like large companies and homeowners, tend to borrow on longer terms.

So, why are long-term rates rising, and why now? As I have argued in the past, long-term rates were already set to rise regardless because of supply and demand conditions for US Treasuries. While supply continues to climb, based on high fiscal deficits, demand has been shifting to more price-sensitive buyers. It’s not that there is a dearth of demand for Treasuries, it’s just that today’s buyers have a greater need to be adequately compensated for risk than the buyers of the past who bought mainly for the purpose of maintaining currency reserves.

What complicates the story is that these supply and demand factors have been in place for a while, but the effects have been temporarily subdued because of decisions made by the Yellen Treasury. Those decisions prioritized easy financial conditions in the short-term for the longer-term cost of higher interest costs to US taxpayers. Andy Constan posted a nice analysis of the situation.

The question now is whether the incoming Treasury Secretary will adhere to the same policy tradeoffs or not. So far, it looks like the market is guessing, “Not”. As a result, traders are probing to find where more market-based long-term rates should be and the degree to which new Treasury leadership will allow them to get there.

The result is a greater amount of uncertainty about rates. One of the ways in which that gets reflected is through a rising term premium. As Andy Constan also points out, this isn’t about growth or inflation. With the inauguration in a week and a half and the next Treasury Advisory Borrowing Committee (TBAC) meeting in early February, we’ll be getting some incremental insights soon enough.

Investment landscape I

As we rapidly approach the inauguration of a new administration, we are forced to grapple with a paradox that has eluded an easy explanation: How will Trump, who is well-known to be impulsive and unpredictable, be able to create and maintain an environment of stability in which investors can feel reasonably comfortable taking risk?

As a long time follower of the political process, economic policymaking, and the investment landscape, John Mauldin is especially well-placed to weigh in on the issue. In his latest weekly letter, he highlights the overturning of the Chevron rule by the Supreme Court last year as being a likely source of instability.

For starters, Mauldin recognizes there are tradeoffs with the Chevron ruling: “To the extent that bureaucratic overreach is reined in, the economy will be more efficient. To the extent that guidelines and rules are relaxed beyond the point of what is really needed, it could create a Wild West.”

However, he also notes an evergreen business reality: “Business professionals and entrepreneurs like predictability. The next few years will be anything but predictable.” Bottom line, he concludes: “It will be quite chaotic.”

The stability paradox is also paired with the debt paradox: “How can the incoming Trump administration cut taxes AND reduce the debt burden?” Mauldin responds glibly, “It is going to take a crisis to get the deficit and debt under control.”

This establishes two broad possibilities. The first is that we stumble along for a few more years without getting the debt under control, but without allowing it to get totally out of control either. Essentially, more of the same.

The second is that we get a crisis. I suspect this is a higher probability than investors are expecting. While a crisis is usually a big challenge for you and me, it is a gift for politicians who want the authority to change things.

Investment landscape II

Out of Sight, Out of Loan ($)

https://www.yesigiveafig.com/p/out-of-sight-out-of-loan

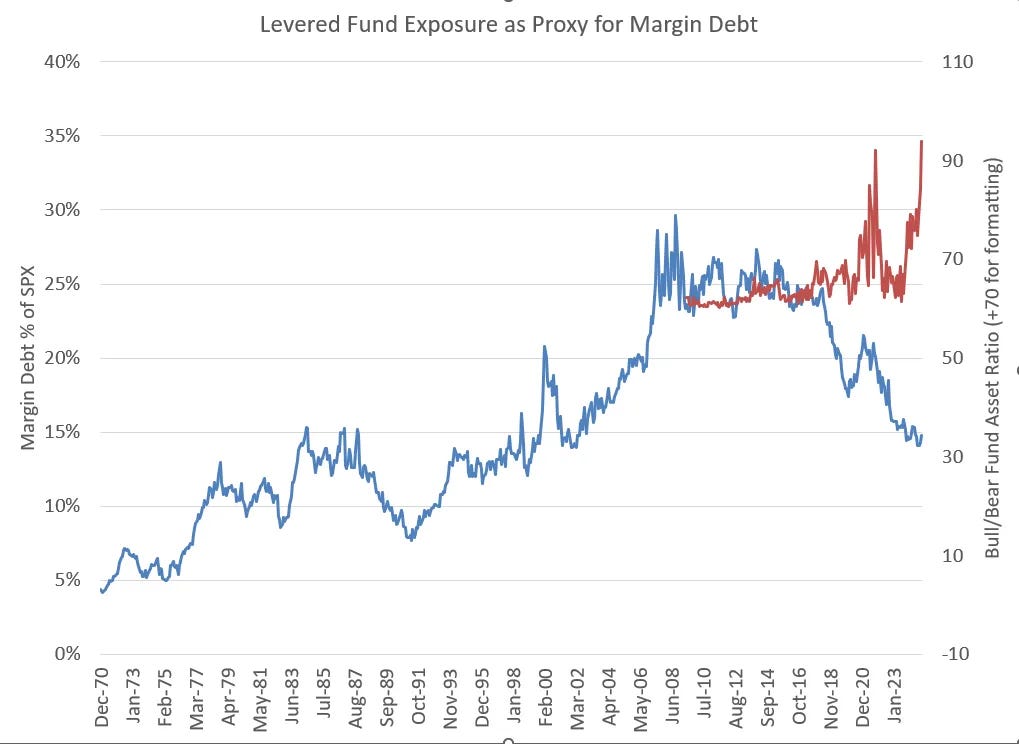

If we proxy these levered funds as alternative for margin debt, the data “fits” remarkably well. If this is right, nearly $1T in additional leverage has been added in the last 15 months:

One of the most common forms of “innovation” in the financial services industry is to find new and creative ways to add leverage. As Mike Green rightly points out, one of the recent manifestations of this innovation has been for leverage to find its way into various leveraged ETFs. As he puts it, “So where’s our margin debt? It’s now INSIDE the funds where it has been largely ignored by regulators”.

So, one consequence is old indicators of leverage such as margin debt are becoming not only not useful, but downright deceptive. Another is that the environment for increasing leverage used to be much better when everyone was looking in the wrong place. Those days appear to be coming to an end as Green warns, “regulators are starting to wake up”.

Investment advisory

How much happiness does money buy? ($)

https://www.economist.com/christmas-specials/2024/12/19/how-much-happiness-does-money-buy

By contrast, the “Merton share” [method for allocating assets] calculates the proportion of a portfolio to place in risky assets from factors that are obviously relevant. It says that the share in risky assets should be equal to their excess expected return over that of the safe alternative, divided by both the investor’s risk aversion and the square of the risky assets’ volatility.

Except in rare circumstances, everyone with savings should buy at least some stocks. Provided their expected return is greater than the risk-free yield on bonds, the Merton share is always greater than zero. The flipside is that, very rarely, no one should own stocks.

All this poses a puzzle. Virtually anyone who studies postgraduate finance, says John Cochrane of Stanford University, will learn about Mr Merton’s framework. Yet among practitioners, and especially wealth managers, it is astonishingly poorly adopted and often unknown.

The Economist does a nice job of highlighting yet another tale of useful investment insight mainly failing to help ordinary investors. As it turns out, the widely used 60/40 allocation to stocks and bonds is not the result of any kind of theoretical insight. Rather, it is an arbitrary weighting that emerged because it happened to work for a period of time.

Those who are more interested in planning for an uncertain future will find the Merton share approach intuitively appealing:

Possibly the most attractive feature of the Merton share is its prescription for responding to changing market conditions. An investment strategy that adapts in light of new information—such as a plunge in prices that has raised expected returns—is one that many will find easier to stick with.

Indeed, this is exactly what I meant in last week’s Outlook piece when I indicated a major tenet of my investment philosophy is “things change”. Yes they do. This happens in every part of our lives and we adapt … an accident on the highway forces us to take a different route or a meeting gets rescheduled and we have to change our calendar. Investing is no different.

If conditions change and you don’t, you can get stuck in traffic a long time, miss an important meeting, and worse. By the same token, my measures indicate the expected return on stocks currently is considerably negative over the next ten years. This situation is rare over the course of history, but real nonetheless. Why would anyone not want to adapt and avoid that adversity?

Portfolio strategy

One of the reasons risk is so often misjudged is because we tend to do so mainly on a relative basis. I may be taking some risks but so and so is insanely speculative. By inference then, my risks are reasonable.

In a recent thread, Michael Pettis shows why this is flawed reasoning.

during long periods of rising prices, those who take on "too much" risk are never disciplined, and so end up systematically gaining market share ftom...

those who are prudent or risk-averse. As a result, if the bull market lasts long enough, eventually most economic agents will have taken on excessively risky balance sheets and – especially worrying in Minsky's view – these risky balance sheets will be highly correlated.

The key dynamic is that in order to mitigate excessive market share loss in a rising price environment, more risk-averse investors calibrate their risk levels to a normal distribution, i.e., on a relative basis. This means as prices continue to go up, the distribution of risk shifts to ever-higher levels in a fairly mechanical and unintentional way.

In the last regular edition of Observations I exhorted readers to not just think differently about risk but to also think a lot about risk. The point Pettis makes is an excellent one. Higher levels of systematic risk have more to do with extended periods of rising prices, and the lack of discipline they facilitate, than individual misbehavior. It’s not just what you or anyone else does, it’s what the market doesn’t do.

While the dangers of higher systemic risk are obvious to the biggest risk takers, others should not be so smug. Indeed, it may be the risk averse that are most surprised by the absolute level of risk in their portfolios.

Implications

One of the great (of many) lessons from John Lewis Gaddis’ book, The Landscape of History, is that different perspectives on a situation yield different insights, each of which contribute to incremental understanding.

For example, viewing monetary policy through the lens of the time period from the GFC through the pandemic, it is easy to conclude that policy prioritized the inflation of risk assets. As a result, it is not a stretch to assume that while the Fed tightened policy to fight inflation in 2022, it was only as an emergency measure which would eventually be returned to normal.

By the same token, viewing monetary policy through the lens of the time period from the pandemic through to present, it is easy to conclude the Fed’s excessively easy response to the pandemic contributed to the flareup in inflation and had to be reversed. Rates had to be reset to levels that were more normal historically in order to keep inflation at bay. While financial conditions were eased during the emergencies of the gilts crisis in the fall of 2022 and the US banking crisis in early 2023, it would only be a matter of time before returning to normal.

In these two cases, “normal” means very different things, and have very different implications for the market. I continue to believe monetary policy fundamentally shifted after the pandemic. While stocks have had a big run the last two years, that was due in no small part to the suppression of long-term rates. As long-term rates rise and reconnect with underlying fundamentals, other long duration assets like stocks are extremely vulnerable. The last two years may well have been a mirage in an otherwise desolate landscape.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.