Observations by David Robertson, 11/10/23

Markets spent most of the week trying to figure out what in the world happened last week. Let’s start sorting through the evidence.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

Stock performance leveled out this week, taking a breather from a crazy week last week. Interestingly, the recovery was focused on the big tech stocks and high beta stocks. Other stocks saw little respite.

Volatility continued to get pounded down. After almost hitting 22 two weeks ago, the VIX volatility indicator dropped below 15 this week. As @SoberLook reveals, the eight consecutive declines in VIX (through Wednesday) is the longest streak in the last eight years.

At least some of the more cautious tone of the week was due to big Treasury auctions. The 10-year auction on Wednesday wasn’t terrible, but it wasn’t good either. It was enough to firmly reverse the decline in yields.

The 30-year auction on Thursday, however, was not good as the yield ended up over 5 basis points higher than the market yield just before the auction (For more details on Treasury auctions see this great thread by James Lavish). Obviously traders misjudged the lower prices required to complete the auction. Further, dealers were forced to pick up an unusually large portion of the issuance and even more duration is the last thing in the world they wanted.

Also, very quietly and in the background, the Japanese yen has continued weakening past 150 yen to the dollar. This is a level at which Japan’s Ministry of Finance had intervened in the past but clearly things have changed. The new level for the yen will be significantly dependent on the BOJ’s interest rate path, but both will be a guessing game for the intermediate future.

In short, then, the wild collapse in longer-term rates last week seems mostly to be a function of a confluence of factors which, in this case, all happened to point in the same direction. Powell said as much when he noted “the risk of being misled by a few good months of data” at an IMF meeting Thursday (h/t John Authers, Bloomberg). As a result, it looks like that move was overdone, and quite possibly, significantly so.

Economy

With many cross currents still swirling through the economy, the ability of consumers to deal with higher interest rates is an important factor. Parker Ross posted a nice summary of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s recent report, “Credit Card Delinquencies Continue to Rise—Who Is Missing Payments?”. The answer, according to Ross, is:

Hint, it's everyone, but mostly:

Millennials

Households who also have auto & student loans

Lower income households

Those with the most credit card debt outstanding

In one sense, this is unsurprising. Of course, the people with the fewest resources to harness are likely to have the most trouble absorbing the incremental costs of higher interest rates.

This evidence also tells another story, however. That story is the ones who are getting hurt most are those who are most reliant on credit for consumption. Even though wages have risen considerably since the pandemic, many consumers still rely on large amounts of debt.

It would be a mistake to jump to the conclusion that Americans are necessarily hurtling toward a recession, however. Axios provides some valuable perspective: “The share of Americans who have debt in collections is hovering at a historic low”. So, even though there is some incremental weakness, “people are paying their bills”.

These two factors, increasing delinquencies but still historically low debt collections, indicates we are in a period of adjustment more than a big cyclical downturn. Consumers who have relied on increasing credit balances are needing to recalibrate spending to their income levels instead. Some are in a better position to make this adjustment and some will take a while longer. In the meantime, the outcome of this adjustment process will factor significantly into whether the economy slows down a little, a lot, or not at all.

Credit

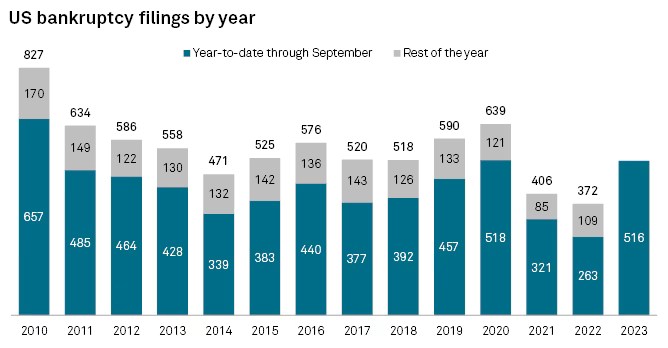

One line of thinking has it that credit is rapidly deteriorating and the economy is at imminent risk of collapse. The chart below from S&P Global and featured in the FT’s Unhedged newsletter ($) does show bankruptcies rising significantly this year. Both the change and the levels are exaggerated, however, by pandemic policies and exceptionally low interest rates after the GFC, both of which artificially suppressed bankruptcy filings.

The FT concludes, “Bankruptcies will be high this year, on current trends, but not disastrous”. This seems about right. As the FT also adds, “Part of the reason for this is that companies are making money.” True enough.

This raises a couple of important considerations regarding the credit environment. One is it is probably more accurate to characterize recent weakness as at least as much of a normalization process as a business cycle downturn.

Another consideration is the economy is transitioning away from credit-driven growth. Ultimately this is a good thing. Companies and individuals that can only survive on the basis of easy credit divert resources from more productive entities. While the process of culling bad credits will be painful for some, it is an overstatement to consider it a doomsday scenario for the economy.

Commodities

I have been keeping an eye on commodities for a couple of years now waiting for an opportunity to increase exposure. This desire is based on long-term under-investment in production capacity, long-term cycles which suggest outperformance of commodities over equities, and the significant potential for higher inflation.

That longer-term goal has been offset by short-term conditions and tactical considerations, however, and those were borne out in spades the week or so. In the US, weaker labor conditions and the collapsing 10-year yield indicated slower growth. On Tuesday, China reported declining exports and Germany reported industrial production that fell further into negative territory.

The aggregate effect of these reports was probably best captured by oil prices which have fallen steadily from around $90 on October 20 to $76 by Wednesday. Part of this was the reversal of a geopolitical risk premium, but a big part was due to concerns about demand destruction.

So, the challenge to add exposure to commodities continues. The long-term case still holds, but this week proved just how brutal the short-term costs can be if you enter too early. I fully expect the tug-of-war to continue, but in the meantime, a lot of commodities and commodity stocks are quite a bit cheaper than they were just a couple weeks ago.

Politics

Where does the US presidential election stand one year out?

https://www.gzeromedia.com/by-ian-bremmer/where-does-the-us-presidential-election-stand-one-year-out

A New York Times/Siena College poll of registered voters in battleground states released over the weekend found that Biden trails behind Trump in five of the six closest states (Pennsylvania, Michigan, Georgia, Arizona, and Nevada). This is largely driven by a massive – almost implausible – erosion in Biden’s support among young and nonwhite voters, who were core components of the coalition that put him in the White House.

The 2024 election is likely to be just as close [as the 2020 election]. Polls consistently show that most Americans dislike both Biden and Trump and would rather not have to choose between them. That both candidates will have a narrow path to victory is guaranteed.

The New York Times/Sienna College poll came out last weekend and sent the political pundits into gear. The main message is Biden is looking weak in most of the swing states he won in 2020.

This would be good news for team Trump if not for the reality that “Trump is still just as unpopular as he was in 2020 (if not a bit more)”. Further, Tuesday’s election revealed strong performance for Democrats in general. The implication is the problem with the Biden ticket is Biden, not the relative position of Democrats.

So, one takeaway is a head-to-head Biden/Trump election will likely be extremely close. Another takeaway is neither candidate is very popular. This fact itself seems to imply some big changes in the political landscape in coming years regardless of who gets elected.

Geopolitics

Michael Pettis says the quiet part out loud in regard to China’s efforts to boost its economy:

Having local officials direct a huge increase in investment into manufacturing, even though private sector manufacturers have been reluctant to expand production, suggests that bad investment in property will simply be replaced by bad investment in manufacturing.

As China contends with slowing growth, two things are becoming increasingly evident. One is efforts to reinvigorate growth are not working. Another is it is extremely difficult for China (or any country for that matter) to change its growth model. As Pettis puts it, “After 30-40 years of solving every problem by expanding investment, it is hard to get the system to change tactics, even when the problem is itself excess investment.”

This isn’t just a problem for China, but for the rest of the world given its disproportionate share of exports. As George Magnus notes, “And this is an imp thread for implications of this shift for rest of world, global trade imbalances, and trade and fx tensions, none of which are good.”

So, not only does continued excess investment forestall China from sustainably transitioning its economy, it also raises the hackles of global trade competitors. Magnus also notes, “Expect more pushback by countries likely to be forced to absorb China’s expanding surpluses.”

If the best China can do is fall back on policies that have the effect of provoking global trade partners, there is likely to be a sustained source of geopolitical friction for the foreseeable future.

As Pettis notes in a separate FT article, however, China faces more than just a little geopolitical friction. Without some accommodation from the rest of the world on trade, it won’t be able to grow with its export-based economy:

The point is that without a major, and politically difficult, restructuring of its sources of growth — away from investment and manufacturing and towards an increasing reliance on consumption — China cannot raise its share of global GDP without an accommodation from an increasingly reluctant rest of the world. Without that contentious accommodation, the global economy would find it extremely difficult to absorb further Chinese growth.

It’s hard to see how significantly constrained growth will make China’s geopolitical disposition any sweeter.

Monetary policy

How the Fed might deal with a US default ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/d71673a2-ce56-40c5-a8c3-31384c2731f7

. . . unless otherwise directed by the Committee, the Desk intends to accept defaulted securities in these operations in the same manner as other Treasury securities, with the prices determined through competitive bidding.

MR. POWELL: As long as I’m talking, I find [these options] to be loathsome. I hope that gets into the minutes. (Laughter) But I don’t want to say today what I would and wouldn’t do, if we have to actually deal with a catastrophe on this.

CHAIR BERNANKE. So you are willing to accept “loathsome” under some certain circumstances. (Laughter)

MR. POWELL. Yes, under certain circumstances.

In an effort to learn more about possible policy options in the event of a US default (presumably due to a debt ceiling impasse), Nathan Tankus unearthed an FOMC memo from 2011 that discussed exactly this topic. The FT article summarizes the findings.

In short, the Fed has all kinds of flexibility to step in and accept defaulted Treasury securities as if they had not defaulted. In the context of Quantitative Easing (QE), the Fed could buy defaulted Treasuries just like normal Treasuries. It could also accept defaulted Treasuries for securities lending.

The main point is the Fed has a great deal of capacity to ease many of the pain points that would be caused by a default. Further, since the options have been on the table for some time, presumably they could be implemented quickly. As a result, the fallout from a default would likely be something less than epic doom.

The exchange between Powell and Bernanke also reveals something about Powell’s disposition, and probably the Fed’s in general. Even when certain policy options are “loathsome”, it is possible to imagine scenarios in which the alternatives are even worse. There are priorities and smooth functioning of the Treasury market is at the top of the list. If that is ever threatened, don’t doubt that every option is on the table.

Investment landscape

With the benefit of a little extra time, it is easier to put the huge move in Treasuries a week ago into perspective. In short, aggressive positioning on the short side and fresh data that revealed incrementally slower economic growth provided a one-two punch to the upward trajectory of longer-term Treasury yields.

Of course there are also many nuances to this basic setup. One take has it that Treasury Secretary Yellen lost her nerve. As 10-year yields hit 5% she did what she could to ease the strains. Plausible. However, just as plausible is possibility she wanted to provide a shot across the bow of Treasury basis trades that had become quite aggressive. Also plausible. Or perhaps, she wanted to provide an olive branch to China, which has been suffering under a relatively strong US dollar, in front of her meeting with He Lifeng this week? Finally, none of these possibilities are mutually exclusive. Yellen could have eased up on longer-term bond issuance for any, or all, or none of these reasons.

Yet another possible reason for easing the longer-term bond issuance is to buy some time before other policy kicks in. As CrossBorder Capital and Stimpyz hint at in an exchange on X, greater capital requirements and/or other controls on leverage are “never bullish”. In plain English, if the problem is insufficient demand for Treasuries, part of the way to solve that is to make leveraged financial companies own more Treasuries. If such a rule is in the making now, which I suspect there is a good chance it is, then Treasury just needs a little more time before it will benefit from structurally higher demand for longer-term Treasuries.

While this will certainly help keep yields from exploding higher, there is no magic formula for matching supply to demand and no one knows what price (yield) will be required to bring in incremental demand. What we do know is deficits are projected to remain high and Treasury bond issuance will need to continue apace or risk weakening the dollar. In the meantime, as the adjustment process plays out, it is fair to expect overreactions in both directions.

Investment strategy

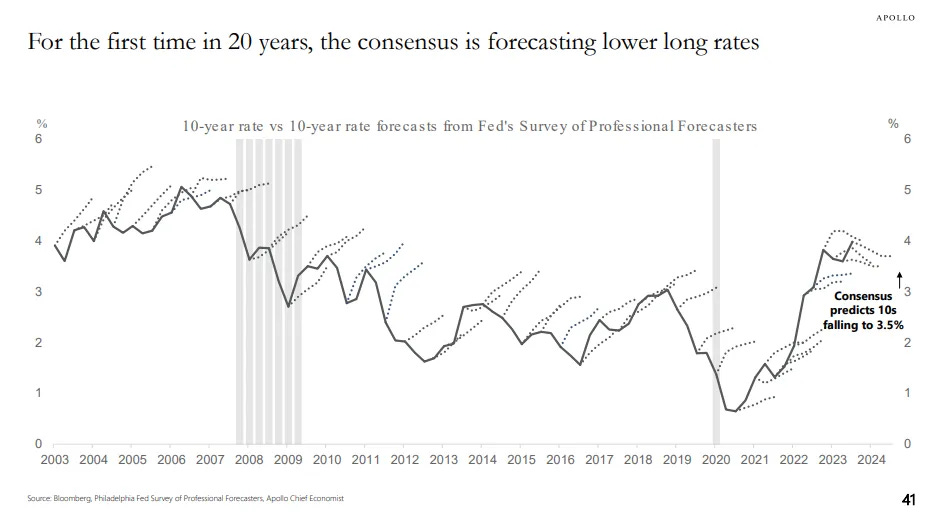

It is interesting for me [Russell Clark] to see that the professional forecasters for the first time in 20 years think bond yields are too high. They seem to have learnt the lesson of the GFC and its aftermath too late! This [graph below] is taken from an Apollo presentation, but you can find similar charts at most investment banks. What this says to me, is that economist and forecasters completely missed the bond bull market, and now that rates are higher, they are not going to miss it again. Its this type of mentality shift that tends to lead to sustained bear markets.

More and more of the foreign holdings of treasuries are flowing from official holders (read central banks) to private sector holders. To me this implies that pricing should become more important. Central banks are price insensitive. Private sector is price sensitive.

Russell Clark sheds some light on the landscape amidst the outsized moves in bond yields recently. One point is that Treasury demand is shifting from the official sector to the private sector and as it does, it is also shifting from price-insensitive buyers to buyers who care very much about price. This has been the prevailing force behind rising bond yields the last couple of years.

Importantly though, the private sector is not one homogenous entity. Rather, some buyers are individuals who are finally seeing bond yields that provide them respectable income. Other buyers, however, “completely missed the bond bull market” and are anxious to replicate that trade.

Needless to say, the motivations of the two groups are different - which means their “price sensitivity” is different as well. The former group will probably provide a fairly stable source of demand for Treasuries. Whether rates go up or down a bit doesn’t matter a lot; they are still way better than close to zero.

The latter group, however, is clearly acting opportunistically. As a result, price level is less important, per se, than change in direction. What this implies is these investors are more interested in the potential for capital gains, due to price appreciation, than for investment income. As such, this source does not present a stable source of long-term demand for Treasuries.

Assuming deficits keep increasing, and Treasury continues to prefer funding mostly with longer-term Treasuries, and no other major buyer steps in, Treasury yields will need to continue rising until enough demand is created to match supply. In the meantime, traders will periodically be making bets along the way that the top in yields is in.

Implications

One characteristic of current markets that continues to impress, and not in a good way, is their ability to quickly and substantially change direction on risk perception. Essentially, risk is perceived to have short duration. Sure, problems arise once in a while. But the perception is they don’t persist and they sure don’t compound into far bigger problems. As a result, volatility bounces around, but never remains elevated for long.

If this seems unnatural, it’s probably because it is. To date, the de facto regime of capped volatility has served policymakers well. It has enabled a normalization of interest rates while mitigating the risk of an uncontrolled decline in asset prices.

The question for investors is how long is this regime likely to continue to serve the interests of policymakers? What will cause them to change tack?

The biggest risk is inflation. When the imminent risk is recession, unnaturally strong asset prices help cross the valley. Once economic growth picks back up, however, inflated asset values pose a huge risk for spiraling inflation. So, policymakers have various levers to pull and adjust in order to manage inflation risks against growth. Once growth solidifies and inflation picks back up, there will be less utility in maintaining high asset prices.

This poses a number of challenges for long-term investors. During the interim, investors are left to contend with inflated asset prices while deriving little to no value from insurance policies and hedges. This leaves investors with the choices of tactical allocation and cash (i.e., Treasury bills) as the main forms of protection for the time being. Not perfect, but way better than nothing.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.