Observations by David Robertson, 11/1/24

As the election approaches next week, most market action is being explained away by political narratives. Let’s take a look at what’s going on.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

Despite fairly mediocre results over the last month, The Daily Shot shows investors are more exuberant than at any point in the last thirty-five years.

At the same time, Barchart shows institutional investors have unloaded US stocks at the fastest rate in nine years:

In short, this looks suspiciously like “dumb money” providing exit liquidity for “smart money”. While such a generalization should always be treated somewhat lightly, it is occurring at the same time as another curiosity …

As Alyosha notes in his Substack,

I have also noticed an obvious omission in Trump’s rhetoric: he never mentions the stock market, ever. He couldn’t shut up about it in 2016 and 2020…Read into that what you will.

Interesting observation. Why would Trump avoid that particular topic unless he thought it was going to be a liability? At very least these examples provide some balance to the popular narratives droning on about a late year melt-up.

In addition, as The Daily Shot ($) graph below illustrates, the Chinese yuan has been getting weaker over the past month. For the time being, this is not getting much attention partly because it is a reversion of an unusual strengthening since the mid-summer and partly because it remains well within the range it has traded the last couple years.

It would be wise to observe this weakening with some trepidation, however. In the midst of a deepening balance sheet recession, China has run out of palatable policy choices; all that is left are tough choices. One of those is to devalue its currency and that is probably the least bad choice. If the yuan continues to weaken, and breaches the 7.25-7.30 area, the move could signal a broader effort to devalue — which of course would have huge implications for the rest of the world.

Watch this space.

Japan

A few weeks ago I mentioned Japan elected a new prime minister but that political turmoil still clouded the direction policy might take on several important issues. After the snap election last weekend, the FT ($) reports the results:

Voters delivered a harsh rebuke to the ruling coalition, led by the Liberal Democratic party, stripping it of its parliamentary majority for the first time in 15 years. Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba is under pressure to resign just weeks after he took office and called the snap election.

As a result, political turmoil continues with no clear path forward. In response, as the FT notes, “The yen fell almost 1 per cent against the dollar on speculation that political paralysis would delay further interest rate rises in Japan.”

The analysis by John Authers ($) at Bloomberg was similarly circumspect and featured this assessment by David Roche of Quantum Strategy in Singapore:

What is sure is that policy uncertainty will rule while the haggling goes on. On a global scale, this is of course volatility in a teacup. But then Japan is a society that likes the calm of the tea ceremony. So, a storm in teacup matters to assets. I expect the yen to weaken. Equities will mark time (the bull period is over anyway). JGBs will stagnate waiting to learn about the next bout of futile fiscal largesse or lack of it.

As Japan goes through the unfamiliar process of having to form a ruling coalition, the policy permutations expand considerably beyond the set of dealing with one dominant political party, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). As Gzero reports, in order to gain a majority, the LDP may be “forced to make concessions on monetary policy. The Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan, LDP’s biggest opposition, proposes modifying the Bank of Japan’s inflation target from 2% to one ‘exceeding zero,’ which would leave room for rate hikes even if inflation dips.”

So, it may very well be this little dustup in Japanese politics ripples all the way out to global monetary conditions!

Housing

While house prices continue to remain strong on an aggregate basis, cracks are beginning to show in some regions. According to one report on the Dallas/Fort Worth area from QEInfinity:

This is insane

Boots on the ground Intel on the surging foreclosure activity in the DFW area from a house inspector.

His business literally can’t keep up with the surge in foreclosures

He said things are only getting worse

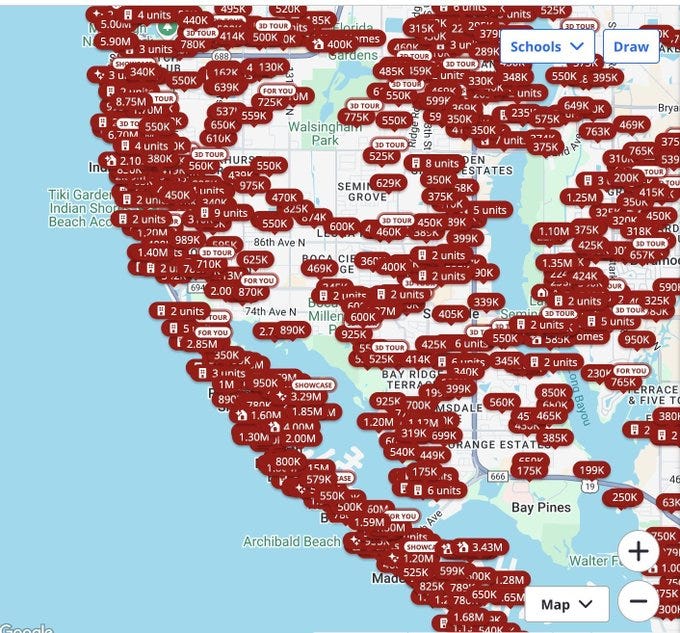

Another post from Financelot shows emerging problems in Florida:

Number of Florida houses for sale just skyrocketed. What are the odds these are all Airbnb rentals with owners who are about to declare bankruptcy?

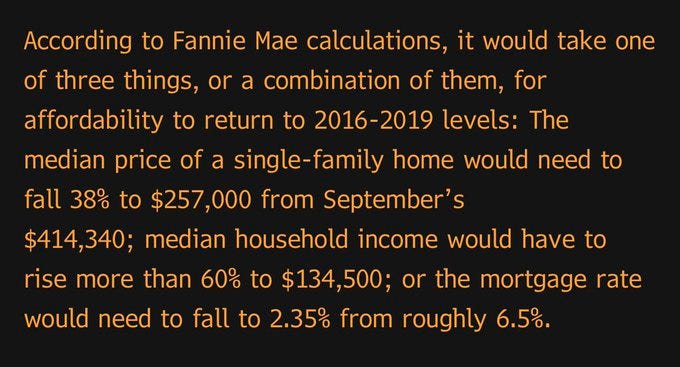

None of this is to say the housing market is an unmitigated disaster, but it is to say that not everything is hunky dory either. Many of these emerging issues were overshadowed by anticipation of the eventual decline in mortgage rates this year — which promised a return to more benign conditions. As mortgage rates have started working their way higher again, though, those hopes have been dashed.

Now, a harsher, uglier reality about housing is beginning to set in. Spencer Hakimian posts an outline of what it will take to restore housing affordability. It’s going to be hard and it’s going to take a long time — and that realization is going to start hitting the housing market.

Monetary policy

The Treasury came out with its Quarterly Refunding Announcement this week and virtually nothing changed. In one sense this is good as it signals debt funding is on something like autopilot for the intermediate future. In another sense, however, there were a couple of warning flags.

For one, the debt funding scenarios assume fiscal deficits will remain about the same for the next three years. This understates the pressure that will be felt as interest, healthcare, and defense costs are all likely to increase over that time. Further, Treasury itself noted “Uncertainty regarding future funding needs remains relatively high” and an area of “meaningful evolution in the Treasury market” was that of “Large structural deficits leading to rapid Treasury market growth”. In other words, don’t be surprised when fiscal deficits turn out to be higher.

For another, Treasury announced it “does not anticipate needing to increase nominal coupon or FRN auction sizes for at least the next several quarters”. This sounded disingenuous the first time it was used a couple of quarters ago and even more so now. Filling funding gaps with short-term bills is fine on a temporary basis, but risks destabilizing the entire system if relied on too heavily for too long.

While there is certainly plenty of room for interpretation, the most likely reading is that Treasury is scared to death of what will happen if/when auction sizes for bonds are increased and demand is simply not there. Yields would rise and reveal for all to see that US finances are unsustainable. This suggests Treasury will continue playing a game of chicken with markets by financing deficits with short-term bills. Sooner or later, the market will start winning.

Investment landscape I

It’s the growth, stupid ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/a3ac86e0-0428-4dd0-aa48-3755b4fceeb7

Surely it’s the “why” [bond yields rise] that matters more than just the direction? Ie, why bond yields are changing dictates the nature and extent of the impact on stock prices. If bond yields are rising because inflation is high and the central bank is about to step on it, then absolutely that should be a headwind for stock prices …

But if yields are rising because growth expectations are rising (but monetary policy isn’t expected to counteract that fully) then the negative effect on multiples via discount rates can be counteracted by the implicitly rising expectations for future earnings . . . I’d argue that latter point is true today — hence why the curve has been steepening and only half of the rise in nominal yields has come from the rise in real yields

With the longer-term Treasury yield being an incredibly important input into financial asset valuations and a regular subject of market narratives this year, it was absolutely appropriate for Robert Armstrong at the FT’s Unhedged newsletter to address the topic.

Indeed, the degree to which bond yields should affect stocks depends on what information the yields are revealing. If they are primarily revealing strong earnings growth, there is no strong reason why higher yields should impinge upon stock valuations. On the other hand, if higher yields on long-term bonds are a reflection of monetary policy that is too loose for current conditions, then higher rates should be a “headwind for stock prices”. This seems to be an increasing concern.

This reasoning is valid on the margin, but it also lacks context. Historically, 10-year yields have traded fairly close to nominal GDP growth. As CrossBorder Capital shows, that relationship has broken down the last couple of years to where nominal GDP is now much higher than 10-year yields: “Current 10-year yield 4.2% Vs 8% Nominal GDP?”

Where should 10-year Treasury yields be based on current economic growth? CrossBorder throws out 6% as a ballpark guess. I’ve seen other estimates in the neighborhood of 5-5.5%. Regardless, this analysis suggests yields are more indicative of a certain amount of suppression more than growth or monetary policy.

The unpeeling of the onion doesn’t stop here either though. As Bob Elliott points out, the rise in bond yields is not isolated to the US, but rather is a global phenomenon, even where growth is far weaker. As he puts it:

Taken together this is a pretty acute move both out of these countries bonds, but also out of their currencies, suggesting a pretty full scale withdrawal of capital from global sovereign debt markets and currencies, particularly if thought about in gold terms.

Once again, the context is not big enough; we need to go beyond growth, monetary policy, and history — and look at sovereign bonds on a global scale. What Elliott illustrates, is that it is not the monetary policy of any one country in respect to its growth rate that matters so much as the generalized pattern across several countries:

The combination of a commitment to 'over easy' money from central banks and continued expansionary fiscal policies across governments are driving this trend to continue. It creates an increasing risk of a challenging repricing of higher risk-premiums and discount rates ahead.

As a result, the consequences are every bit as global: if most of the world’s largest countries are all running monetary policy that is too loose for conditions, risk assets everywhere will get re-evaluated.

Investment landscape II

One factor that seems to have been driving markets the last couple of weeks is prediction markets. Jim Chanos describes the phenomenon:

A lot of market participants I talk to are positioned for an almost-certain Trump victory. When I ask them why, virtually every one of them has pointed to the September/October move in the betting markets, toward Trump.

Jim Bianco posted a thread arguing the prediction market data seems valid. However, Ben Hunt unequivocally rejected the usefulness of Polymarket results in particular: “The fact that $3m clears the ENTIRE ORDER BOOK for Polymarket should be enough for people to realize this is a complete sham.”

Chanos follows without mincing words:

Which begs the question if tens of millions of $ can move/maintain these betting odds on the unregulated offshore sites, but are impacting trillion $ global markets (US Treasuries, etc), what prevents the legal “gaming” of these election odds?

Personally, I’m with Chanos in suspecting that betting markets are being “gamed” in regard to election odds. For one, there is a broader game at play in which if you want to “manage” a narrative, you manage the “data” from which a narrative is formed. There is now plenty of evidence that government data has a suspicious pattern of reinforcing government narratives and that mainstream media has a bias to framing news in certain ways. Why would it be any different for social media or betting markets?

Rusty Guinn describes the process in a great piece for Epsilon Theory ($). As he puts it:

What changed common knowledge [on Polymarket] was a few people moving a lot of money in a thin market and the man with the biggest PA system in the world [Elon Mush] seeking to manufacture consensus by shouting into the void that this is real.

This is, and has been, one of the biggest investment challenges of the last fifteen years. When a consensus can be manufactured (and it can), common knowledge can be established that is even more powerful than the underlying reality, and therefore creates a type of reality on its own. When common knowledge and underlying reality are at odds, investors must choose. Underlying reality wins out in the end, but common knowledge can rule for a long time.

Gold

While gold prices continue to do well, thoughtful analysis on the metal still trails considerably. As a result, I thought it might be helpful to post these comments by Tony Deden and reposted by Simon Mikhailovich:

An excerpt from "Gold: The Resilient Reserve" by Tony Deden:

"What makes gold compelling are the risks we do not take by owning it. No forecasting or guesswork is required. The risks we do not take owning gold could fill volumes. With gold, there is no duration risk, credit risk, or liquidity risk. The metal is not moved by financial instability nor threatened by national insolvency or chaos in foreign exchange markets. There are no margin calls and no refinancing risks. There is no risk of technological obsolescence, depletion, depreciation, or decay, nor does it require cheap energy, cheap credit, or cheap trade to remain viable. It does not care about your national energy policy or who you buy your gas from or how many pipelines are running. You do not have to keep the lights on or even keep it warm. There are no financial accounts to pore over, no balance sheet to blow up, no cash flows to dwindle, no stale inventory and no margin pressures in difficult times. There are no key manpower or supplier risks, no competitive risks, no management to squander its future. It does not depend on the character, skill, or enthusiasm of any one. It does not require the faith or good will of others. It does not require you to trust anyone at all, except that you must hold it in a very safe place."

Bottom line: Gold is the only universally liquid financial asset that is no one's promise, which is why demand for it rises whenever trust in promises declines.

With investors happily riding on the coattails of strong S&P 500 returns the last couple of years (not to mention the last fifteen years), perceptions of risk have eroded to the point where virtually no risk is perceived at all. That doesn’t mean risk has disappeared though.

As a result, these notes from Tony Deden on gold provide both a sober and timely reminder of all the things that can go wrong with stocks. As such, the examples also provide a good refresher on why a healthy risk premium is normally demanded for owning stocks.

It wouldn’t be at all surprising that as many of the noted risks of stocks become realized with greater frequency, the appreciation for gold will grow even greater. Still early days.

Implications

While investors seem content for the moment to interpret stock and bond prices in the context of national markets, there is a growing risk that global phenomena will supersede local happenings as the key drivers of asset prices.

One reason is there are limits to how far global imbalances can grow and we are approaching them. For many years, the US could accept higher debt in return for modest unemployment and cheap Chinese goods. Today, that tradeoff is far less attractive and quite arguably, counterproductive.

As a result, it is fair to expect the arrangement to change. One way it can change is for the US to impose policies designed to correct its trade imbalances. Another way for the trade arrangement to change is for non-US countries to withdraw investment in US assets and instead redirect them into local markets. Either way, there will be less international support for US assets.

This will put major US stock indexes at risk as well as the fixed income universe. While I’m sure there will be a preference to avoid a disorderly selloff, the Liz Truss moment in the UK proved politicians don’t necessarily have a good sense of how fragile their markets are. As a result, the priority of preserving assets remains greater than the priority of growing them.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.