Observations by David Robertson, 11/17/23

Stocks continued their upward march this week, but leveled out after the CPI report on Tuesday. Bonds continued higher as well, but with a lot of chop. Let’s put it in context and figure out what it means.

I’ll be off next week for the holiday. Hope you have a Happy Thanksgiving!

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

The CPI report on Tuesday made a big splash as the headline number came in cooler than expected with no change from the prior month. The softening was especially noteworthy compared to much higher readings the last two months.

The market didn’t need to be told twice. Stocks shot out of the gate on Tuesday and the 10-year yield got hammered down as investors assumed the tame inflation number would be sufficient to prevent any further tightening by the Fed.

For better and worse, all the tightness that had occurred from higher long-term rates unwound quickly. As John Authers illustrated, financial conditions went from being fairly tight to being balanced in a couple of weeks.

This is consistent with a comment Michael Kao posted (from a Barclays piece) indicating the sluice gates for the high yield market are wide open:

In other news, Heather Long posted an interesting tidbit on housing. As the average age of a repeat home buyer keeps edging up, it’s no surprise that many of the buyers are Baby Boomers, often with all-cash deals. The more interesting bit is that “70% of recent buyers did NOT have children under age of 18 in their homes”. Apparently, this is “the highest share recorded, and well above 42% in 1985”. Not exactly the American Dream, huh?

Labor

Will it Hold?

https://www.nexteconomy.co/p/will-it-hold

Today’s post reviews most recent labor market trends and explains why some alarm bells should be ringing at the Fed and the Government - the only two parties that can both slow spread of unemployment and aid those affected. It also spells out why a benign outcome may still be possible, and why the risks are high this time, should unemployment indeed begin to rise

Several employment trends are now at levels that have historically always lead to significantly higher unemployment

While no one knows what will happen yet, I think the likelihood that things evolve - at the very least - differently than expected are high. Covid has blown up most traditional economic models. This could once again apply to the labor market, which also faces unprecedented demographic change

This analysis by Florian Kronawitter provides some nice perspective on the labor market. Yes, there are a number of trends that are concerning in that they “historically always lead to significantly higher unemployment”.

However, and it’s a big “however”, the historical record may not be super useful because the chance that things evolve “differently than expected are high” due to Covid. Very fair.

This backdrop makes for an exceptionally difficult and uncertain environment for making policy. Add on the pressures and public scrutiny during an election year next year and there is all kinds of opportunity for policy mistakes to be made.

Geopolitics

China Ready To Improve Ties With US 'At All Levels': VP

https://www.barrons.com/news/china-ready-to-improve-ties-with-us-at-all-levels-vp-1a5ae0c5

Beijing is ready to hold talks with the United States at "all levels", China's vice president said Wednesday ahead of an expected summit in San Francisco between leaders Xi Jinping and Joe Biden next week.

Speaking at the Bloomberg New Economy Forum in Singapore, Chinese Vice President Han Zheng said recent high-level meetings between Beijing and Washington were sending "positive signals" that relations were improving.

While I am extremely skeptical relations between the US and China have changed very much, let alone on the scale described in the article, Pippa Malmgren posted her endorsement of the sentiment by saying: “This is the signal I have been looking for! Geopolitics has become too expensive for China. They want to reach some kind of a new deal with the US.”

If true, this could change things on a lot of fronts including the level of geopolitical risk and the strength of the US dollar. Stay tuned.

Monetary policy

Bill Dudley: inflation wasn’t caused by too much money ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/079e1706-5118-4e7f-a0dd-e182b520deb6

Unhedged: What’s something you’d say isn’t widely appreciated about monetary policy today?

Bill Dudley: A lot of people still don’t understand the importance of the shift in the Fed’s operating regime to an excess reserves regime, where they set the rate on reserves [often known as the interest rate on excess reserves, or IOER] as the primary tool of policy.

All of a sudden, you get the ability to pay interest on reserves. That allows you to cut that link: you can now have a big balance sheet but still control the economy. It allows you to offer open-ended liquidity facilities, without worrying about how much they’re drawn down. In the lead-up to the GFC, the Fed had to be very careful about the facilities not getting too large, because if they got large, we’d have to turn around and drain all the reserves that were added through the liquidity facilities. The facilities had to be set up so that the added reserves wouldn’t be unmanageable.

Apparently, Dudley’s comment, “Bwahahaha ... and then we can rule the world!” got edited out of the final transcript ;-) Seriously though, Dudley’s comments provide a great deal of insight into the Fed’s thinking and mentality.

The main point is the Fed has transitioned monetary policy. It used to rely on setting rates as a mechanism to calibrate the proper supply of money. That became bothersome on a number of occasions, however, when market distress caused severe tightening of financial conditions and rates couldn’t really go any lower.

Now, with the excess or ample reserves regime, “Quantities of money don’t really matter very much. What really matters is the interest rate that the Fed sets on reserves.” This gives the Fed a great deal more flexibility to react to, and even prevent, major market crises. That means a repeat of the 2019 repo crisis or the 2023 banking crisis is unlikely.

The additional flexibility of the excess reserves regime comes with costs, however. No longer are there material constraints on the Fed’s balance sheet; that is determined arbitrarily by the Fed. Further, as John Hussman pointed out nearly two years ago, the point at which the Fed pays out a higher interest rate to banks on excess reserves than it takes in on its purchased bonds, which is where it’s at today, it has crossed into fiscal policy.

Now that’s some wonkish stuff for sure, but it has important implications. For example, while nobody is complaining about the Fed engaging in fiscal policy now, if higher inflation were experienced in the future, it’s not hard to imagine some acrimony being directed at the Fed. Indeed, the Fed’s independence could be at risk and it could be dissolved altogether if sentiment became negative enough.

This begs the question of why the Fed is taking such a big risk? Clearly, it is deemed more important to reserve policy flexibility now than to ensure the longer-term integrity of the Fed as an institution. This is a crisis mindset. It tells us that market functioning for the foreseeable future is more important than anything else. Including inflation.

Investment landscape I

Forget the S&P 500. Pay attention to the S&P 493 ($)

Regarding the S&P 493:

Most obviously, having discarded the tech behemoths, our new index now looks substantially older. Consider its biggest companies. At the top of the list is Berkshire Hathaway, an investment firm led by two nonagenarians, and Eli Lilly, a pharmaceuticals-maker established in the 19th century by a veteran of America’s civil war. Further down is JPMorgan Chase, a bank that made its name before the founding of the Federal Reserve. That is not to suggest that these firms do not innovate. All of them, by definition, have remained highly successful, even if none has crossed the $1trn threshold. Whippersnappers, though, they are not.

One of the most important market phenomena this year has been the superlative performance of big tech stocks, aka the Magnificent 7, relative to the rest of the S$P 500 index constituents. These stocks, comprising Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla, have risen 52% in the first ten months of the year. “By contrast, the value of the S&P 493 fell by 2%”.

The wildly divergent performance is important for a couple of reasons. For one, it makes it all-too-easy to conflate the performance of the stock market in general with that of the big tech stocks. If the S&P 500 is doing fairly well, most stocks must be doing fairly well, right? The answer is, not so much. The exceptional performance of the Magnificent 7 has masked the far weaker performance of smaller stocks.

The differentiated performance of the Magnificent 7 is often attributed to their differentiated business models. As opposed to the far more staid constituents of the S&P 493, the big tech stocks are much younger companies as, “Each was established in the past 50 years, and five of them in the past 30”. Younger companies, younger cultures, and fresher technologies are simply more dynamic - or so the argument goes. While there is truth to it, it is not the whole story.

Russell Clark provides a different view of the big tech stocks. He sees them as a combination of tax arbitrage and private equity plays. On one hand, as Clark explains, “As more and more of the economy has moved digital, this means more and more of the corporate tax base has shifted to a ‘tax free zone’.” In short, the Magnificent 7 have the business mix to locate intellectual property in tax havens for the purpose of reducing corporate taxes. They also have the global size to do this at scale. It results in a unique and significant cash flow advantage.

He goes on to explain, “This cash [earned abroad in tax havens] cannot be easily returned to US shareholders, as its offshore, but it can be used as collateral for loans to buy back shares. This has the added benefit of being tax friendly for shareholders.” So tax savings get recycled into buybacks which provide a constant bid for the stocks. As Clark concludes, “In essence, the US capital markets [are] increasingly dominated by the activities of international tax arbitrage and capital return in a tax efficient manner.”

So, while the Magnificent 7 stocks certainly have their fundamental reasons for outperformance, that performance is also dependent on public policy choices - which in turn are dependent on politics, i.e., public acceptance. With increasing pushback against tax avoidance and excessive market power, it looks as if the days are numbered for such activities. As Clark puts it, “But one day, politicians will have to choose between taking on corporates, or being voted out of power.”

In conclusion, there are several reasons why the performance record of the Magnificent 7 may turn down - and take the S&P 500 with them. For one, it is unlikely unfair tax and corporate practices will remain viable politically. Additionally, it will be increasingly difficult for the big tech companies to maintain high growth and high profitability, especially being as large as they already are. As a result, the likelihood of a downturn for the Magnificent 7 is quite high, even if the timing is less clear.

Investment landscape II

Lisa Abramowicz posted these comments on bond positioning this week:

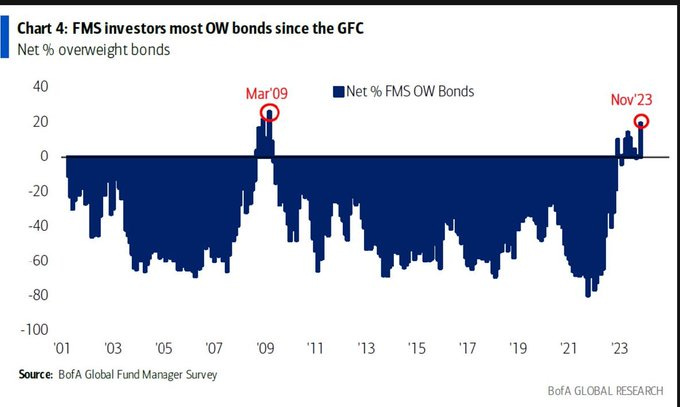

BofA’s latest fund manger survey showed investors were dumping cash to hold the biggest overweight position in bonds since 2009. The “big change” was not the macro outlook, but expectations that inflation and yields will move lower in 2024.

The last time there was a huge shift to being overweight bonds was during the GFC when investors sought safety amongst a landscape littered with investment carnage. With stocks within spitting distance of all-time highs and the economy plugging along nicely, that obviously is not the case this time. As Abramowicz highlights, the big shift into bonds has not been driven by the macro outlook, but rather by the market’s inflation expectations.

This speaks volumes about the environment in which investors must operate. Bond buyers aren’t so much trying to adapt long-term allocations based on the risk environment as to position for directional trading.

For one, this illustrates just how risk-seeking the marginal investor is right now. Rather than resigning oneself to realizing decent returns on cash, that investor would rather make a directional call on inflation. For another, it exposes the increasing risk being taken on by investors. If the economy does not collapse, and/or if inflation re-accelerates, bond holders are likely to suffer.

Investment landscape III

The Confidence Map: Charting a Path from Chaos to Clarity, by Peter Atwater

To be confident, we need our “C & C.” We need to feel things are predictable—that we have certainty in what is to come—and we need to feel we have the right preparation, skills, and resources to successfully steer our way through it—that we have control. When we are confident, we believe we will land safely and successfully on the other side of what’s next.

Though we don’t typically think of it in these terms, the opposite of feeling confident isn’t lacking confidence as much as it is feeling vulnerable. Vulnerability is what we experience when we feel that we lack certainty and control—when we feel somehow threatened, when what is ahead seems unclear and we feel powerless against some troubling force.

Normally, when I come across themes like “confidence”, and “sentiment”, and am presented with a 2x2 matrix, I roll my eyes expecting another superficial Harvard Business Review-like simplification of an otherwise difficult problem. What I have found thus far from Peter Atwater’s thesis (also addressed in an interview with Grant Williams ($)), however, is something far more thoughtful - and practical.

As he explains, “feelings of vulnerability drive much of our decision-making”. True enough. For those of us who have studied behavioral finance, we know that we often respond to stress in three different ways: Freeze, fight, and flight. Interestingly, and usefully, Atwater adds two more to the mix: Follow, and f***-it.

As Atwater explains, people follow when “speed and ease are what matter most—and when they are provided by a familiar, trusted source, we quickly get in line”. Unfortunately, we can be impulsive at times and become victims of those who are “Masterful at providing compelling tales of certainty and appearing to be in full control”.

The fifth response to stress, f***-it, is when “We simply quit, believing the situation is meaningless and/or unwinnable”. Atwater goes on, “Instead, we play our own game, choosing to do things our own way, despite what others think—often to the detriment of others and ourselves … We equate disruption to victory, knowing full well we may never win in the end. We think, if we can’t win, neither should others.”

Does this sound like any behavior you have encountered? I know all kinds of lights when off flashing in my head when I read this. Whether trying to understand our own behavior or that of others, and in contexts ranging from markets, to politics to society in general, Atwater’s model clearly provides a great deal of explanatory power. While many extreme behaviors may initially strike us as bizarre and uncalled for, a good deal of the time they are just recognizable reactions to stress. And that is useful to know.

Investment strategy

“The Center Cut”

https://www.convexitymaven.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Convexity-Maven-The-Center-Cut.pdf

Today I will detail a new Strategy for investing in mortgage-backed securities (MBS), the bond market’s second largest asset class. This strategy trims off the “older” bad bonds from the MBS Index and allows civilians to purchase only the “newer” better bonds usually available only to professionals.

“A New Issue MBS Strategy”

https://www.convexitymaven.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Convexity-Maven-MBS-Strategy.pdf

I [Harley Bassman] think the Yield Curve will power steepen later next year as the economy slows via a rotation around the 10yr, which is the dream scenario for this Strategy.

There are several insights to glean from these two recent pieces by Harley Bassman, but I will try to focus on the most important ones. The first is there truly are opportunities for differentiated performance in the markets. When 30-year mortgages are set at less than 3% one year, and then go for almost 8% less than three years later, they create investments with very different characteristics. This is obvious to almost everyone. Unfortunately, passive funds have to buy (and hold) whatever is out there. They can’t cherry pick, but active investors can.

Another point is Bassman’s investment approach very much parallels my own in a philosophical sense. There are opportunities out there that astute analysts can find and there are opportunities to make them accessible to investors at a fair price. I call this the right way to do investing.

So, one point is a lot of investment organizations don’t do this very well and many don’t even try. There are still good ones though. Another point is this doesn’t mean active management is all good or passive management is all bad. It just means there is a place for both.

Implications

While the rally in stocks and bonds over the last three weeks has been impressive, it has not been especially informative. Prompted by favorable data reports (namely CPI), the rally was facilitated by positioning as much as anything. Until something changes more fundamentally, the most reasonable expectation is for more bouncing back and forth within a range.

Tellingly, the big moves in markets have focused more on backward-looking data points than on evolving structural factors. There are lots of reasons for this, but none of which are of particular interest to long-term investors. For them, the view is more of shorter-term easing of inflation data while longer-term structural pressures continue to build.

This being the case, the biggest upcoming issue for long-term investors is to manage reinvestment risk. At some point, it is likely short-term rates will come down and when they do, cash will be a less rewarding investment. As a result, it is a great time to start building a list of investment ideas and to use the market swings to redeploy cash opportunistically.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.