Observations by David Robertson, 11/22/24

There wasn’t a whole lot of market news this week but there was a lot of political and geopolitical news. Let’s dig in.

Also, as a reminder, I’ll be off next week for the holiday and return on December 6. In the meantime, I hope you have a really nice Thanksgiving!

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

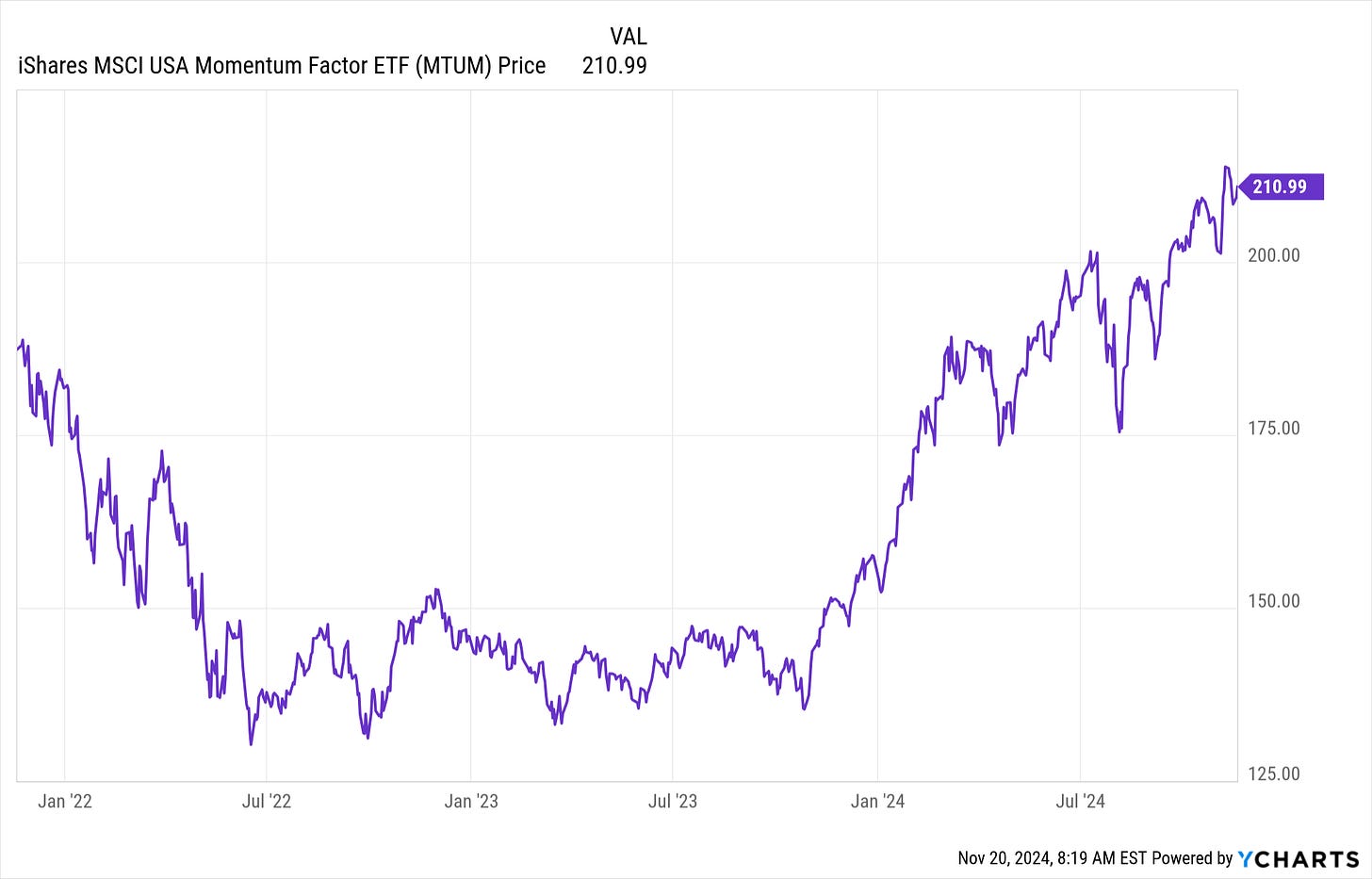

One of the outstanding factors over the last year has been momentum, captured below by the MTUM ETF.

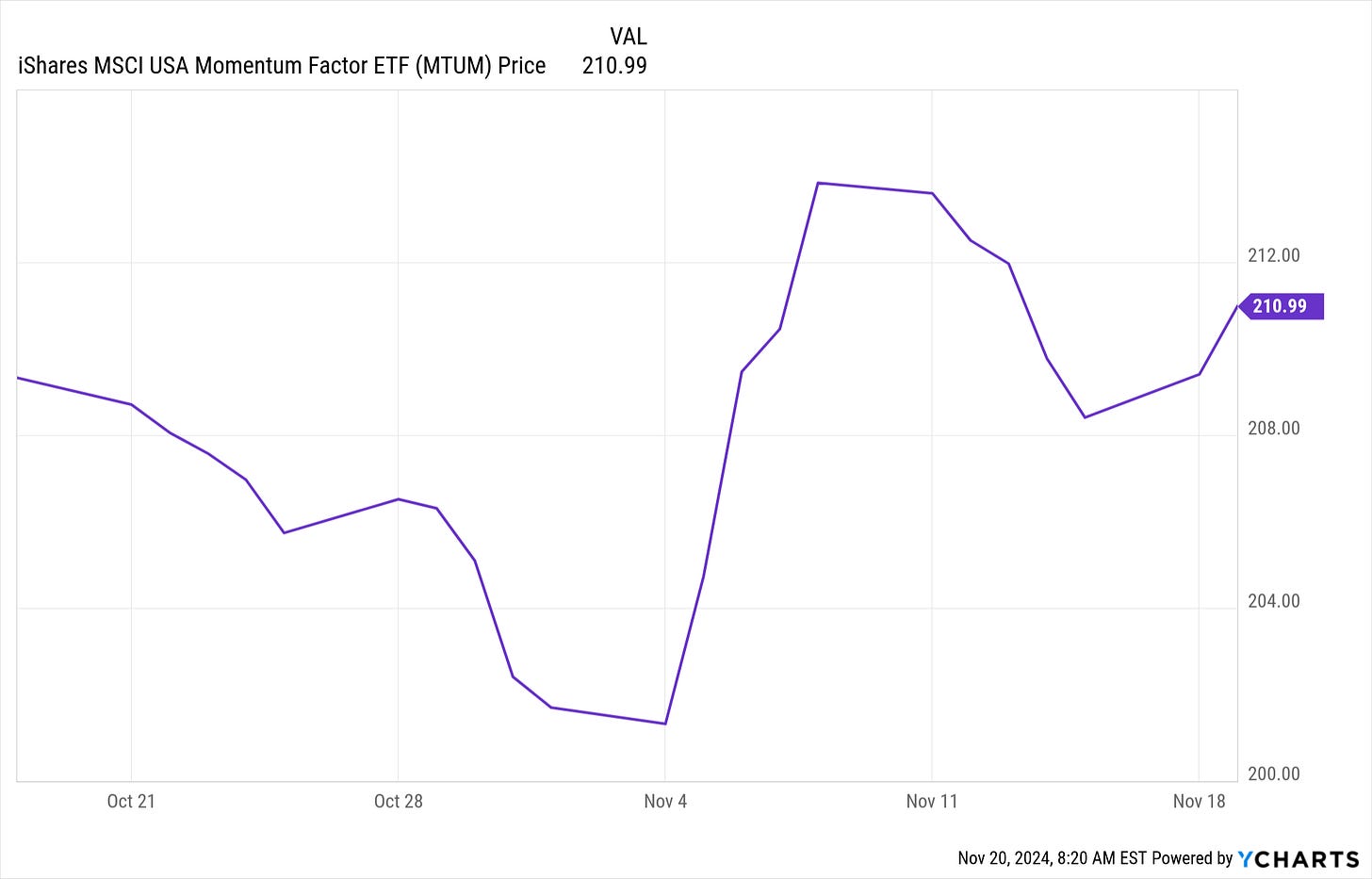

A closer look at recent returns, however, gives a very different impression. While MTUM sold off going into the election, it rallied hard for a few days afterward. Since then it has languished not all that far from where it was a month ago. One shouldn’t read too much into this, but it could be an early indication one of the key market drivers is showing signs of exhaustion.

Another market indicator that is showing some signs of worse things to come is insider sales. With the ratio of sellers to buyers (from the Daily Shot) at the highest level in the last twenty years, it sure doesn’t look like insiders are nearly as enthusiastic about their stocks as retail investors are.

Nor do things appear to be much better in the market for small private businesses. As the Daily Shot also reveals, “record activity” and “growing discounts” are appearing for private company shares as private equity firms press to increase liquidity amidst challenging business conditions and limited opportunities for exit.

Politics I

What initially appeared to be a solid start to presidential appointments following the election has quickly devolved into a much messier affair. A big part of the recalibration of the political environment was due to the evolution of the contest for the Treasury appointment. What started off as a two-horse race opened up to include other prospects. At the same time, betting odds have been bouncing all over the place.

As Michael Pettis notes, there is some reason for optimism. A Secretary of Treasury from a different mold could be just what the country, and the economy, needs:

More generally, I'd argue that the next Secretary of the Treasury should be more committed to the interests of US manufacturers, producers and workers than to the interests of Wall Street and the owners of movable capital. That would be something new in American politics.

On the other hand, the delay in the announcement seems to be indicative of the kind of horse trading and internecine warfare that prevailed in the first Trump administration. Insofar as this is the case, it would be a bad omen for what the administration can accomplish.

Politics II

HOW THE IVY LEAGUE BROKE AMERICA ($)

Over time, America developed two entirely different approaches to parenting. Working-class parents still practice what the sociologist Annette Lareau, in her book Unequal Childhoods, called “natural growth” parenting. They let kids be kids, allowing them to wander and explore. College-educated parents, in contrast, practice “concerted cultivation,” ferrying their kids from one supervised skill-building, résumé enhancing activity to another. It turns out that if you put parents in a highly competitive status race, they will go completely bonkers trying to hone their kids into little avatars of success.

The good test-takers get funneled into the meritocratic pressure cooker; the bad test-takers learn, by about age 9 or 10, that society does not value them the same way.

It’s a rare treat that an article so captivates me I can’t stop thinking about it and how it explains so many puzzling phenomena. This article by David Brooks is one of those masterpieces. It contains insights about politics, culture, education, leadership, and more.

The basic premise is that an ostensibly well-intended effort that began in the 1950s to recruit college students more on the basis of meritocracy has gone horribly awry. For example, “the system overrates intelligence” at the expense of other important attributes. It creates a rigged game that selects more on the basis of parents’ financial ability to prepare their kids than on innate ability. Further, it creates students who “learn to become shrewd players of the game, interested only in doing what’s necessary to get good grades”

The end result is a “meritocracy [that] has provoked a populist backlash that is tearing society apart.” As Brooks describes, “working-class people resent the know-it-all professional class, with their fancy degrees, more than they do billionaire real-estate magnates or rich entrepreneurs.”

As a person who grew up under “natural growth” parenting but who also went to highly ranked colleges, Brooks’ distinctions and implications resonate deeply. They help explain why so many financial services firms have such poor value propositions and they help explain why I get irritated with a lot of “know-it-all” professionals too.

They also help explain one of the bigger mysteries for me — why does so much academic and intellectual activity get directed to efforts that don’t create value for society? Why do so many smart, educated, well-trained people seem to care not much or at all about their impact on others?

The answer Brooks provides is “not to end the meritocracy”, but rather “to humanize and improve it”. He redefines merit about the “four crucial qualities” of curiosity, a sense of drive and mission, social intelligence, and agility.

Sounds like a great start.

Geopolitics

As the US prepares for what might come with the new Trump administration, so too does the rest of the world. One fairly safe assumption is that Trump will prioritize immediate American interests above all else. This implies greater self-sufficiency in defense for American allies but also greater self-sufficiency in economic growth.

As John Authers ($) highlights, using the UK as an example, one way a country can promote greater self-sufficiency is to invest a greater proportion of its savings within the country and toward growth-enhancing projects (i.e., equity):

The move into bonds [from UK pension funds] reduces risk and ensures funds can match their liabilities to pensioners, both important goals. But it has come at the expense of capital for productive investment in the UK. With the fiscal situation strained, the government cannot prime the pump, even if it wanted to. So the imperative is to make whatever technical changes are needed to persuade more money to invest at home, starting with the pension system. Without this, the country will have difficulty generating growth needed to lance the pain of higher price levels.

Even more important, this very same logic applies to virtually all US allies, including Japan which invests massive sums in US markets. While changes are unlikely to happen quickly, they are likely to cause a significant and sustained withdrawal of capital from US markets. Unless these moves are offset with incremental inflows, they are likely to have a very negative effect on the prices of US financial assets over time — just like they have had a very positive effect over the last few decades.

Investment landscape I

Why financial markets are so oddly calm ($)

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2024/11/14/why-financial-markets-are-so-oddly-calm

One thing nobody thinks of Donald Trump’s return to the White House is that it will herald four years of quiet, predictable government. Here, then, is a puzzle for readers interested in the more abstract bits of finance. Why was Mr Trump’s re-election greeted by resounding drops in volatility all across the world’s most important markets?

An instinctive understanding of risk allows for this wild randomness in ways that a statistical measure such as volatility cannot. That is especially true for options traders, who, if asked for a contract insuring against too extreme a move, will simply name a price high enough to dissuade the buyer. Investors, in other words, do not think Mr Trump’s presidency will be predictable. They think its unpredictability is unpriceable.

While this piece from the Economist raises an important point, it also does so while misrepresenting another one. First, the technical construction of major volatility indexes like the VIX involve one-month measures of volatility. As a result, it is typical for volatility to increase as soon as a major election comes into that one-month window. By the same token, volatility drops the day after the election because that major event is no longer in the one-month window.

Even with that completely foreseeable drop in volatility after the election, however, financial markets do seem “oddly calm”. For the explanation of this, the Economist is spot on: major volatility indexes don’t include wild, unquantifiable events … exactly because they are wild and unquantifiable. Dealers will simply offer such an absurdly high price so as deter a transaction.

As a result, volatility indexes end up only including the types of volatility that are easily foreseen and quantified. In normal conditions, this works fine. As the breadth and depth of unquantifiable risks increases, however, the information content of such indexes erodes considerably.

By all appearances this is happening now. It also serves as a good heads up to resist slavish adherence to purely quantitative measures of risk.

Investment landscape II

As a long-term oriented investor, I focus a lot on valuations as a guide for asset allocation. As is fairly widely appreciated, however, valuations are not a good guide for shorter-term market action. This is why I get especially interested when short-term trading insights also happen to dovetail with longer-term valuation insights.

According to PauloMacro ($) in a recent Substack, this appears to be happening now:

In a nutshell, the key points of the topping formation and subsequent rollover — a phenomenon I am calling the Rollover Syndrome — boil down to:

A loss of momentum into a topping pattern (head & shoulders, impulsive collapse, etc)

A curling down of the 200 day moving average, which is often tested from below.

A shifting investment Narrative of deteriorating fundamentals or flows that reflexively confirm the price action.

Further, the Rollover Syndrome appears to be widespread. Evidence is apparent in the French stock market, the weight loss drug makers, and Microsoft, among others. Perhaps most importantly, though, the pattern is also emerging in semiconductors:

But the most troubling one setting up now is in the semiconductors. I am hearing more and more about how that China’s analog semi capacity is ramping to frighteningly large levels, and the world will soon drown in chips the way we are drowning in Chinese autos, solar panels, etc. What if this narrative becomes consensus? A breach and test of the 200dma would certainly be a death knell:

The S&P 500 got a big bump after the election, but has been giving it back over the last week and a half. The leading light of the market, Nvidia, also got a big bump after the election bust has been flat since. A strong earnings report on Wednesday was greeted with a yawn.

While speculative interest seems to be as strong as ever, increasingly it is running into resistance rather than broadening the rally. It’s just not a good sign when shorter-term risk indicators start aligning with long-term risk indicators.

Investment landscape III

When I look across the S&P 500 as an analyst, I see so many things that make me seriously doubt the suitability of the index for retirement portfolios. Yet, at the same time, investors and advisors keep directing money into the very same index. Let’s take a look at some of the things that give me pause on arguably the most popular investment in the world.

One item is the phenomenon of elasticity I mentioned last week. What this boils down to is the stock market currently behaves like a Ponzi scheme. As long as money keeps flowing in, prices keep going up. While the market is unlike a Ponzi scheme in that stocks do have intrinsic value, elasticity pushes prices well beyond those values. That means most likely some day prices will fall a lot.

Price elasticity also means the big keep getting bigger. When that happens the market becomes increasingly concentrated and reliant on a small number of stocks. This makes indexes like the S&P 500 less and less like the well-diversified representation of the market it was originally intended to be.

Indeed, this is exactly why the most effective long-term valuation measures are at record highs right now. Stocks are simply getting priced way above the future cash flows companies are likely to produce. Today’s stock market is not mainly about efficiently contributing capital to fund productive growth.

In addition, I am increasingly seeing instances of dubious accounting. This is common at the market tops. When there is no realistic way to keep revenues accelerating, companies start cheating. The latest example is Super Micro Computer which couldn’t file its 10Q on time and had its auditor resign loudly. There are signs all over the place though.

Finally, the purely speculative nature of a great deal of market action should also be of great concern to investors who mainly just want to reap the benefits of regular productive investment. One glaring example is MicroStrategy which has transformed its dying software business into a Bitcoin Ponzi scheme. On top of that, the stock trades at over a 200% premium (probably even higher by the time you read this) to the Bitcoin it does own. PauloMacro provided his take:

Behold megacap ponzi in all its glory. I’d say this will all make quite the book in a few years but by the time someone gets ready to publish it there will be stuff that is even more stupid and insane

In the latest edition of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer ($), Jim Grant took the opportunity to fill the entire front page with anecdotes illustrating extreme market action. He captured these under the heading, “View from the crazy train”.

In short, when you put money into the S&P 500 now, you may think you are being a prudent investor, but you are really participating in a “megacap ponzi in all its glory” and riding the “crazy train”.

Investment landscape IV

Upon re-reading last week’s comment about the market structure and elasticity, I realized the main point was not as clear as it should have been. That point is flows become increasingly impactful on market prices when certain flows are more motivated than others. This is the essence of elasticity.

I daresay a great deal of the confusion that arises over this phenomenon can be traced back to college economics classes that assume free and fair markets among a widely diversified group of traders and with no frictions. In such circumstances, there is no a priori reason to believe $1,000 going into stocks is any more or less motivated than the $1,000 coming out.

The problem is markets have changed and those assumptions are no longer valid. This is exactly the point Mike Green makes. When the vast majority of in flows come from price insensitive sources, they are bound to push prices up. Indeed, as the composition of flows from passive investment vehicles and share repurchases has continued to increase, so has the price impact.

Implications

For a lot of different reasons, investing in stocks has become almost automatic for a lot of investors. Better long-term returns relative to other assets, excellent performance over the years, and few perceived risks are frequent justifications. While these reasons are not wholly wrong, now is a particularly good time to reassess the risks of investing in stocks largely because I think a lot of investors and advisors are underestimating the risks they are taking.

While I have highlighted valuation risk for some time, increasingly other risks are also becoming apparent. The increasingly speculative nature of trading, high security concentration in major indexes, the Ponzi-like nature of many markets, the “Rollover Syndrome” in many subsegments, and increasing political uncertainty all scream major warnings. At the same time, perceived risk is exceptionally low.

One implication is stocks are becoming less and less appropriate for retirement savings. Given the heightened risk of big losses, and the inability of most retirees to replace lost savings, stocks pose an unacceptably high risk in many situations.

Of course, the harm from big portfolio losses doesn’t accrue only to retirees. Even young investors who have plenty of time to grow their retirement nest eggs can suffer a debilitating psychological blow when the fruits of their labor get squashed. Worse, severe portfolio losses can then cause young investors to become overly risk-averse, avoiding risky investments like stocks even when they are appropriate and attractive.

The bottom line is this: In general, stocks can be really useful investments. However, there are times when stocks overshoot and present a poor risk/reward proposition. This appears to be one of those times. Plan accordingly.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.