Observations by David Robertson, 11/3/23

It was such a busy week for news that the FOMC meeting almost got lost in the shuffle! Let’s jump right in.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

The S&P 500 persistently weakened the last two full weeks of October, but exploded higher this week. Participation was broad-based, but the biggest gainers were the most-shorted and most-speculative stocks.

The VIX volatility indicator was a prime suspect. Hitting over 22 last Friday due to concerns over escalation of violence in the Gaza Strip, VIX got crushed on both Monday and Tuesday and continued its decline through the week.

Did risk get bid up too high going into the weekend of October 27th? Perhaps. Did month-end volatility selling magnify the reversal? Perhaps. Did the Treasury’s announcement of lower than expected coupon issuance extend the decline in volatility? Almost certainly. The big question is, how indicative is VIX of underlying volatility as opposed to the tail wagging the dog?

In regard to the economic landscape, various cross currents remain making it hard to outline prevailing conditions. Add one more wrinkle into the mix: The opinions of Americans, which have generally tracked actual economic conditions extremely well for decades, stopped doing so after the pandemic. The graph below from the Economist illustrates the growing divergence (h/t Steve Stewart-Williams).

One factor seems to be expectations. The era of ever-lower rates since the GFC not only provided a persistent tailwind for asset values, it also created a persistent tailwind for ability to spend on consumption. With higher rates, tighter credit, and a lull in asset appreciation, the trajectory for future spending has changed.

This may explain why Americans “are behaving as flush as ever” even though they “report being worried about their finances”. They strongly suspect their spendthrift days are numbered, but haven’t yet mustered the energy to cut back yet. Old habits die hard.

India

Chartbook X Unhedged: Investing in India - a "wager on the strong"?

https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/chartbook-x-unhedged-investing-in

In 2020 on the World Bank’s Human Capital Index — which measures countries’ education and health outcomes on a scale of 0 to 1 — India achieved a score of 0.49, below Nepal and Kenya, both poorer countries. China scored 0.65, putting it on par with Chile and Slovakia, which have higher GDP per capita. Most dramatically disadvantaged are India’s women. Since 1990, Indian women’s labour market participation has fallen from 32 per cent to about 25 per cent. And behind them come hundreds of millions of underskilled youngsters. In 2019 less than half of India’s 10-year-olds could read a simple story, compared with more than 80 per cent of Chinese children and 96 per cent of Americans. In the coming decade, 200mn of these poorly educated young people will reach working age.

While this perspective on India is admittedly “more alarmist”, it also makes a valid case that India “is in the late stages of a failed project of nation building.” In doing so, it highlights economic inequality, but more specifically the deterioration in human capital of both women and youths.

This is important because human capital is ostensibly something countries can do the most about to help themselves. Through public policy in various forms, not least of which includes education and training, countries can decide whether to invest in their future - or not.

To this point, when economic inequality and underemployment become big issues, they also become big political issues that limit the degrees of freedom a government has to implement corrective policies. This is also just as true of more developed countries as less developed countries.

Politics

Triumph of the GOP end-of-days caucus ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/a922cb8e-ddaa-484c-a720-e4c4e970304f

I [Rana Foroohar] have been wondering if we may be at one of those weird, rare moments in history where we see the total implosion of one party (a la the Whig party) and the creation of new ones. This wouldn’t happen overnight, obviously, but I can certainly imagine a universe in which the Republican party as we know it ceases to exist and the Democratic party expands and splits into the progressive and more middle of the road factions. Or maybe the libertarians rise and take on the Democrats? There aren’t too many of the former but they are very well funded.

In response to the selection of Mike Johnson as Speaker of the House, Ed Luce sets the stage by describing him as, “the most extreme figure to become US Speaker since the civil war”. Indeed, the selection of such a polarizing figure begs a number of questions. Does Trump really command so much power in Republican politics? Is Johnson just a placeholder to mitigate Republican embarrassment over having no Speaker when Hamas attacked Israel? Are there other schemes being plotted behind closed doors none of us know about?

Or, as Rana Foroohar wonders, is this a moment “in history where we see the total implosion of one party … and the creation of new ones”? Perhaps Foroohar is too narrow in scope in suggesting the “total implosion of one party”. While she is clearly referring to the Republican party, there is no shortage of cat fights over fundamental principles in the Democratic party either. Claire Lehmann writes:

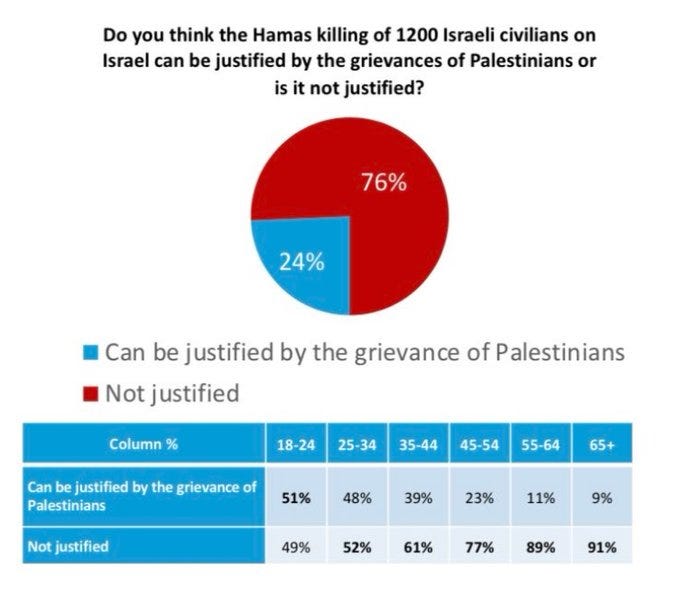

I've been covering the toxic ideology in universities for years. But if you had told me a month ago that this ideology would lead more than half of Americans under the age of 25 to justify & excuse the torture & mass-murder of a minority group, I would not have believed you.

Ben Hunt calls this “the Great Unmooring” and suggests, “Among other social catastrophes that follow from this, the coming schism in the Democratic Church depresses turnout and leads to Trump winning the 2024 election by flipping states like Michigan and Georgia.” So, that sounds like a pretty big problem for Democrats too.

The schisms in both the Republican and Democrat parties look to me to be part of a bigger process. As the needs of society change, so too do its institutions and politics. This is a process Neil Howe describes as a regeneracy and one I highlighted most recently in the September 15th edition of Observations.

The major parties are getting forced apart from both sides: The schisms provide the “stick” for followers to change affiliation and policies that garner bipartisan support (such as pro-labor) provide the “carrot” for them to form new ones.

What this means in political terms is that old associations are far less stable than imagined and new ones far more probable.

Geopolitics

Luke Gromen points out a new phenomenon: “yields on emerging-market bonds in local currencies have fallen below US Treasuries". Count this among the things in finance that shouldn’t happen. Riskier bonds should not yield less than safer bonds.

Brent Johnson followed up with his take: “This is what will pull capital to the US and deprive the rest of the world of the much needed liquidity...” This raises an interesting prospect. What if higher long-term rates were about more than just persistent inflation, rising term premia, and quarterly refunding?

What if higher long-term rates were also part of a geopolitical strategy to starve strategic rivals such as China and Russia of “much needed liquidity”? When US authorities froze Russian reserve assets after invading Ukraine, the US certainly signaled a willingness to use its currency as a strategic asset. By maintaining a strong dollar, the US can impose a great deal of pressure on a country like China which is trying to avoid a disorderly unwinding of its real estate industry.

Further, while higher long-term rates hurt the US in the form of higher interest costs, China is in even worse fiscal condition. As Bob Elliott highlighted, “China is running even bigger government deficits at this point”.

This raises the distinct possibility that higher, or at least more normal, long-term rates are playing a role in contemporary warfare. When you own the global reserve currency, you have a lot of ability to impose undesirable conditions on strategic competitors. To the extent this is the case, it would argue for long-term rates permanently resetting to a higher level.

Monetary policy

For the first time in a long time, the Fed was not the headline act in regard to monetary policy. It wasn’t even the second act.

The most important announcement of the week actually came from the US Treasury. The quantities of funding were announced on Monday and the composition was announced on Wednesday. The most important number, the amount of coupon issuance, came in greater than the expectation published in August, but lower than dealers had expected. It was also lower than I expected.

As Florian Kronawitter summarized nicely, “They [Treasury] caved in face of difficult 10yr/30yr auction and are prioritising bills”. He characterized this as “a huge policy decision”.

He went on to say, “The Treasury essentially told us that whenever the market will get difficult (which it did around 5.5%) it will listen”. The effect: “In the short run, this is positive for risk assets. In the long run, it is another step towards a world of structurally higher inflation.”

One point is the Treasury is clearly making the policy decision right now as to the appropriate range for long-term rates, not the Fed. Another point is there are not particularly good outcomes from either path. Either less high rates now and more inflation later, or even higher rates now and a greater risk of a major accident.

The second act of the monetary policy jamboree this week was the Bank of Japan (BOJ). Weston Nakamura provided his take:

Whoa this is big

BOJ policy statement just got rid of ANY explicit upper band ceiling to YCC (“1%” ← no longer)

Markets now TRULY have no idea where the goal posts are- as it seems BOJ themselves have no idea when / where / how, or IF to step in to JGB markets at all

World is finally without an explicit central bank put for the first time

While it is always dangerous to declare anything too earth-shattering in regard to Japanese monetary policy, Nakamura’s comments deserve consideration. Removing the upper band of its yield curve control is a big thing, though it remains to be seen exactly what this will mean in practice.

In addition, while the central bank put is clearly on the wane, it isn’t quite dead yet. The BOJ’s policy is still extremely loose. In addition, the Fed still has a wide range of facilities it can invoke in an emergency and China is boosting liquidity to cushion the fall of its real estate industry.

Finally, the FOMC also met this week and, as expected, kept rates unchanged. In regard to its future disposition on rates, Chair Powell said the prevailing question for the Committee is, “Should we hike more?” Conversely, the Committee is “not thinking about rate cuts at all.” In addition, the QT program remains on track as is.

Bob Elliott posted a nice characterization of the Fed’s position:

The Fed’s pause is not a data driven decision, it’s a risk averse preference.

If the Fed decided on the actual data below, further hikes wouldn’t be a close call, even at today’s 5.5% rates:

- 8% gdp growth

- 5% real growth

- 3.8% UE rate

- 5% wage growth

- 4% core inflation

So, Yellen balked at increasing coupon issuance due to concerns about even higher long-term rates. Powell is executing the “risk averse” playbook. It may not happen in the next couple of months, but those are some strong signs for higher inflation.

Investment landscape

Great news about American wealth ($)

https://www.noahpinion.blog/p/great-news-about-american-wealth

Not only did every group get richer, but inequality decreased across multiple lines — age gaps, racial gaps, educational gaps, urban-rural gaps, and overall inequality all narrowed over the last three years.

And yet despite the fact that rates went from around 0% to over 4% over the course of 2022, wealth still went up. That means this wealth boom is very different from the increases in earlier decades, when rates were relentlessly lowered. Remember how for all those years we heard that the Fed was “inflating” or “propping up” stocks and houses and bonds by lowering rates and doing quantitative easing? Well, 2022 was the exact opposite of that. And yet the wealth gains didn’t stall out.

That’s a great sign for the future, because it means that if and when rates go down, Americans’ wealth will rise by even more.

Noah Smith makes some good points about American wealth since the pandemic. Mainly, wealth is is broadly up and inequality is broadly down. While there are still clearly people who are struggling, that should not distract from the reality that consumers as a whole are doing fairly well. This is often lost amidst the many voices predicting imminent recession.

Smith also makes some bad points, however. While it is notable household wealth still went up in spite of significantly higher interest rates, it is not fair to conclude that higher rates don’t have any effect on house or stock values. Just because those effects have not been realized yet does not mean they never will be realized. It takes time. Yet, he also highlights the possibility that “if and when rates go down, Americans’ wealth will rise by even more”.

This reveals three beliefs that still dominate the investment landscape. First, you get to have your cake and eat it too. If rates go up, no problem, there is no effect on wealth. If rates go down, yay, wealth will go up again. There are no consequences.

Second, wealth is accurately determined by the numbers on your financial statement. As many homeowners are finding out, just because home prices are still strong overall doesn’t mean you can actually sell your house for a similar high price. That depends on finding a buyer who either has cash or can afford an 8% mortgage. Actual results may vary, by a lot.

Third, and importantly, Smith’s analysis reveals a great deal of ongoing “buy-the-dip” mentality. While it is definitely possible rates will go down and ease conditions, it is far from a certainty. Further, across the broader expanse of history, the current move in rates looks a lot more like a return to normal. A lot of investors are still making decisions based upon an imminent return to low rates rather than adapting to a new, higher rate environment.

For as long as the BTD fervor persists, markets are likely to resist large declines, but at the expense of becoming increasingly susceptible to event risk.

Investment strategy

Halloween hangover No. 16 — the US keeps getting all the treats ($)

The latest study by Schwab Asset Management shows that ETF investors born from roughly 1981 to 1996 have 45% of their portfolios in fixed income. Those are millennials, aged from 27 years old to 42. That compares to 37% for Generation X — those born from around 1965 to 1980 — and 31% for baby boomers. And it goes exactly in the opposite direction from conventional wisdom, enshrined in the “target date funds” that form the backbone of retirement products …

It’s pretty interesting to hear that a large group of investors are doing exactly the opposite of what they “should” do. Conventional investment doctrine recommends investors reduce investment risk as they get older in order to mitigate the risk of large drawdowns at a point in their careers when they have less time and ability to recover.

What the Schwab data shows, however, is younger investors are directing relatively larger proportions of their portfolios to fixed income and older investors relatively smaller ones.

The article chalks up the divergence to conservatism due to millennials having witnessed “repeated market turmoil — from the Global Financial Crisis to the pandemic onset”. Perhaps. Or maybe the system that served their parents so well just doesn’t work nearly as well for them? Or maybe they just want to be more actively in control of their investment plans than a static allocation can provide?

Regardless, the prominent investment in bonds by younger investors says two things. First, in the event inflation persists, or bumps up even higher, there will be a need at some point to provide some inflation protection for that bond-heavy portfolio. Second, regardless of what the doomsayers preach, there is still demand for US Treasuries.

Implications

The Treasury’s announcement of slightly lower than expected issuance of 10-year and 30-year bonds this week touched off a huge rally in stocks and bonds. While the announced quantity was only slightly smaller than expected, it clearly sent a signal: Longer-term rates were getting too high for Treasury’s comfort.

The market took it as a signal that “Happy Days are Here Again” and rallied hard. As Jack Farley highlights, however, that may be a misinterpretation. He notes the new Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC) report indicates there is “some early evidence of waning demand” for US Treasuries.

Some of the potential causes of that waning demand include “Appreciation of U.S. dollar”, “Commercial banks' shrinking portfolios”, “Bond investors thought 10-year would peak at 4.25%”, and “Mechanical increase of duration for mortgages // MBS”. As a result, the slight reduction in longer tenors appears to be an effort to pre-empt any disastrous mismatch of supply and demand of Treasuries that could result in spiking yields. To be clear, waning demand for Treasuries is not a good thing.

The decision to pare back longer-term coupons solves the short-term waning demand problem, but comes with longer-term consequences. One of those consequences is the need to issue a higher proportion of Treasury bills. While the Treasury does have some flexibility around this, persistent, excessive bill issuance will drag down the value of the US dollar.

Another consequence is that lower rates will boost the prices of risk assets. While this is good in the sense of arresting a painful decline, it is bad in the sense of boosting collateral values. Improving financial conditions undermine the effort to bring inflation down.

Yet another consequence of easing up on financial conditions right now is that it flies in the face of the political economy playbook. Typically, an administration prefers to engineer a slowdown in its third year so as to create economic momentum in the election year. Easing conditions now risks forestalling the slowdown until right before the election next year.

While yields did take a dive this week, and risk assets have popped, it is important to keep things in context. At least thus far, the moves aren’t reflecting anything more than a normal (albeit faster than usual) adjustment. As John Authers observes, “This reverse only leaves them [10-year Treasury yields] well within a clearly upward trend”.

Regardless, the clear signal sent with the refunding announcement, combined with the persistence of a buy-the-dip mentality, makes for some crazy ups and downs. While these can create opportunities for traders, mainly they are just distractions for long-term investors.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.