Observations by David Robertson, 11/4/22

It was another busy week with more earnings reports, a big FOMC meeting, and a few market moving rumors for good measure. If you have questions or just want to get some perspective on the whirlwind of happenings, let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

On Tuesday, market futures popped up before open on rumors China was going to reverse its Covid measures and open the country up. Excitement abounded, KWEB (China internet ETF) surged over 8%, and everyone was ready to go off to the races.

The only problem was the rumor was unfounded and as that reality sunk in, the S&P 500 sank quickly at the open and finished down for the day. KWEB, however, held most of its gains.

As Tier1alpha pointed out on Wednesday, “The unexpected improvement in the Job Openings survey [on Tuesday] was enough to send risk markets sharply lower and interest rates meaningfully higher within moments.” As also reported, the numbers surprised the market which had expected some weakness based upon “the unbelievably well telegraphed deterioration in the construction area as evidenced by the Q3 GDP report”.

The chart below (from @SoberLook) details the performance of thematic ETFs and tells a bit of an interesting story. For the month of October, the best performers were cannibis and sports betting while the worst ones were solar and clean energy. While one should not read too much into this, it does say something about where market priorities have been recently.

Credit

Typically, some of the first signs of an economy cooling are widening credit spreads. The reason is weaker companies with heavy financing burdens are the first ones to feel the impact of higher rates and slower growth. To this point, @BobEUnlimited lays out a nice smorgasbord of credit spread indicators to review.

After scanning across the spectrum of credit, Elliott concludes, “I see basically nothing.” As a result, while every downturn has its own unique characteristics, and credit is but one indicator, the overwhelming lack of distress in credit is suggesting the economy is currently chugging along just fine, thank you. The additional read-through is, “Its imaginary thinking that financial conditions concerns are even close to making the Fed change course.”

Japan

This is a really good thread on Japan. One point is Japan’s debt burden is so onerous that it will provide a preview of the “endgame” for other overly indebted countries. Another point is the money chart shown above: Japan has hit the point at which the debt problem can no longer be kicked down the road.

The thread goes through the implementation of financial repression and the various decision branches along the way. At the end of the day, the number of options becomes progressively smaller. You end up with a choice to either raise interest rates “which puts government into a debt-service trap” or , “bring back capital controls” to defend the currency once FX reserves run dry.

This is what happens with persistent can-kicking: You end up with choices which are only bad ones.

Politics

The public aren’t blameless victims in the crisis of democracy ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/eef1c538-c22e-4231-8ade-6c16eeb4b039

Some blame is due [the masses]. In a recent poll by Ipsos for The Economist, British voters agreed by a large margin that economic growth does more good than harm. They just opposed almost every single thing that might bring it about, that’s all. Immigration, housebuilding, spending on science as opposed to pensions: all got a “no”. And these questions weren’t sly or obscurely framed. Respondents were confronted with the trade-offs in explicit fashion: strictly limit immigration even if it harms growth, was one proposition.

Excellent insight into the political landscape from Janan Ganesh which is also generalizable well outside the UK. The main point is there is plenty of blame to go around for bad policies and bad policy ideas, and at least some of the blame should be directed to “the masses”. Sure economic growth is important. It’s just that almost no voter wants to trade off anything of personal benefit in exchange for a greater good. John Kennedy’s request, “ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country,” largely rings hollow today.

This is point I have been harping on for some time. While I definitely do not endorse the wide array of crazy policy ideas out there, I also sympathize with the challenge of establishing policy for electorates who judge policy suggestions on the sole basis of direct personal benefit. The logical extrapolation of this political landscape is less high-level problem solving and more pandering to important political constituents.

Divided government, diminished profits ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/4a4b7440-bbb5-48e5-827c-d9ac2db82f7e

Government spending, and in particular debt-financed government spending, has gone bananas since the start of the pandemic. And as we have pointed out before, deficit spending and corporate profits are closely related.

If we get a divided government, deficit spending will decline even more precipitously than it already is, because no big spending bills will be passed, not even in the “reconciliation” process that the Dems have depended on for the past two years. As BTIG’s Isaac Boltansky puts it, “the only time deficit hawks fly in Washington DC is under a divided government”.

Two excellent points here that are relevant to the trajectory of inflation. First, since debt-financed government spending is a big driver of inflation (and corporate profits), we can expect to see less of it if Republicans take the House and possibly the Senate in the midterm elections. The path towards free spending will be more difficult for sure.

That does not mean the path will be completely blocked, however. Neither party has proven to be especially fond of austerity in recent years and if any kind of emergency arises, all bets are off regarding spending controls.

The big picture takeaway is that debt-financed government spending will continue to drive inflation over the longer-term, but the political landscape may add some twists in the road along the way.

Inflation

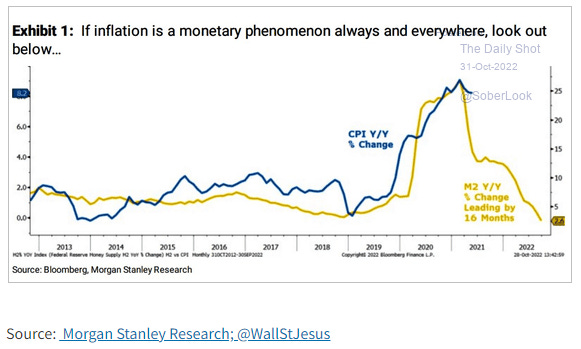

The graph below from @SoberLook is representative of the narrative being told by a lot of pundits and advisors. The story starts with the assumption that inflation is a monetary phenomenon, shows money supply declining substantially, and concludes inflation must be coming down just as fast.

Unfortunately, this narrative is even more representative of what Wall Street does best: Applying partial truths to justify stories investors want to hear for the purpose of maintaining positive sentiment and therefore the proclivity to trade.

Even excepting the reality that M2 is an incredibly incomplete measure of money, the argument has the serious flaw that money supply is not the sole driver of inflation. While inflation is a complicated subject, it is far more accurate to say inflation results mainly from the monetization of excessive fiscal spending than from increasing money supply alone. The key distinction is not even indicated in the graph: Fiscal spending was kept under wraps after the GFC but was unleashed for the Covid pandemic.

As a result, the better indicator of future inflation is the trajectory of unfunded future fiscal spending. With the Inflation Reduction Act and student loan forgiveness in the bag and Treasury bumping up borrowing estimates for the fourth quarter by $150B, the pattern of spending beyond the country’s means is continuing. That said, it is certainly possible political winds will change and work to rein in excessive spending for some time. Neither party has shown much predilection for sustained austerity though.

Investment landscape

I referenced some comments by David Einhorn last week in regard to the value style. As luck would have it, Einhorn talked to Grant Williams and both clarified his remarks and provided some additional insights about the market.

As I suspected, his comments about the value style were directed at the business of investing according to the value style, not the investment approach itself. In particular, He said:

I actually think it’s [value] going to be a very successful strategy and I think that we are in progress of performing much better than we did over the last period of time. But what I’m saying is value investing as an industry has been decimated and I don’t really fully see it coming back.

I couldn’t agree more. Analyzing companies and financials used to be a big business but no more. That means a lot less competition for the people who can and do.

Interestingly too, lack of market interest in value stocks has broader implications. Low market interest means low multiples which means higher cost of capital. Higher cost of capital means higher returns are required to justify investing money to expand capacity. For industries that produce widely used things like gasoline and paper products and whatnot, that means either less will be produced or prices are going up. As Einhorn puts it, “the deprivation [of capital] here, this is causing inflation.”

There are a lot of different ways this situation could develop, but for the time being, the deprivation of capital points to higher prices. The exception would be if demand also falls and lower levels of capacity are required.

Public policy

The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power, by Daniel Yergin ($)

When Doherty, and subsequently many others, talked about “conservation,” they meant such measured production practices, which would aim to ensure the largest ultimate recoverable resource, and not reduced or more efficient consumption. But how was Doherty’s “conservation” to be accomplished? It was here that Doherty shocked most others in the industry. The Federal government, he argued, would have to take the lead, or at least sanction industry cooperation. And there would have to be public enforcement of technologically superior production practices.

Back in the 1920s, the oil business was often literally the “Wild West”. Drillers and capital would chase opportunities wherever there was a whiff of oil. When oil was struck, drillers would produce full out until the reservoir was drained. This led to dramatic swings from overproduction and low prices to periods of fading production and concerns about sufficient supply.

Given the industry’s tendency towards dramatic swings and in the context of the recent memory of World War I, oilman Henry Doherty proposed a more thoughtful approach to drilling by the industry. His plan was to better manage reservoir depletion so as to reduce the volatility of supply swings and also extend reservoir life. This plan had the additional benefit of improving supply reliability in the event the country’s war machine needed to get fired up again. In short, the plan also supported national security.

Today, one hundred years later, some key elements of this paradigm ring as true as ever. While there are certainly good reasons to curtail industry effects on the environment, there are also good reasons to ensure sufficient supply of resources that are essential for ensuring national security. To that point, there absolutely are instances in history during which private sector companies cooperated with government for the purpose of mutual benefit. The idea is not a popular one today, but that doesn’t mean it can’t or won’t happen.

Monetary policy I

Quantitative Buybacks

This is another nice monetary policy explainer by FedGuy, Joseph Wang. It is useful to understand the mechanics involved with Treasury buybacks but it is also useful to understand the broader monetary toolkit the Fed has and to review some scenarios regarding how it might be used.

Namely, to date, markets have largely treated monetary policy as one-dimensional. Quantitative Easing (QE) = good. Quantitative Tightening (QT) = bad. In a similar vein, recent talk about Treasury buybacks has boosted markets.

This narrow view of monetary policy, however, belies the complex challenges confronting the Fed and the nuanced response required to prevent mayhem. To this point, the Fed really has at least three mandates. Price stability and maximum employment are explicitly stated. Maintaining financial stability is not formally stated but is arguably even more important.

With this background, it is easier to see how the Fed might want to continue QT (bad) in order to regain control over monetary policy and to fight inflation but at the same time have the Treasury deploy buybacks (good) in order to ensure adequate liquidity and smooth market functioning. In this way, the Fed and Treasury would work in conjunction to undo QE while minimizing accidents.

While there is plenty of room for miscalculation, the effort makes sense. Investors who don’t see this as a concerted, balanced effort to move in the right direction are going to get whipsawed multiple times.

Monetary policy II

Speaking of whipsaws, the violent rallies based on optimistic interpretations of Fed actions serve a couple of purposes. The first is these violent swings become costly after a while. Allow enough people to lose enough money on this process, and, like @Stimpyz1 illustrates, it’s like breaking a hanger. Eventually they lose enough money and stop.

Which leads to another purpose. While quite cynical, I don’t doubt that there is at least some (and perhaps quite a bit) of intention to allow stocks to rally frequently in order to provide exit liquidity for pensions and other big piles of money. After all, someone has to take all those stocks off their hands if they are going to de-risk.

Implications for investment strategy

A really good point is made here in that the rapid resetting of rates has been the main investment story this year. As we get closer to what the Fed considers neutral on rates, there will be a lot less uncertainty and volatility on where rates move from here. That is not to say rates can’t go higher or can’t bounce around for a while. It is only to say the bulk of that move is behind us and it is time to focus on the next big thing coming.

That next big thing is growth, or more specifically, lack of it. Several industrial indicators are pointing down and inverted yield curves are confirming the prognosis of a slowdown next year. Results from the big tech companies last week also highlight many of the company-specific challenges to growth in the current environment.

Indeed, this could be one of the ways in which investors get “fooled”. It may be that multiples on stocks just don’t come down much from current levels - but revenue and earnings continue to deteriorate. If this turns out to be the case, it will make scrutinizing financials and company prospects a extremely valuable activity once again.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's partar financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.