Observations by David Robertson, 12/13/24

It was another fairly busy news week with very little trading activity. It seems like everyone is just waiting to cash out a profitable 2024. Let’s dig in.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

On Monday morning, after the news Syria’s government had fallen, gold popped and the US dollar (USD) was down. In the context of geopolitical upheaval it is normal for gold to jump, but it is also normal for USD to go up as well. The strength of the gold rally may well have been at least partly a correction of a strong selloff in late November. Further, USD has since resumed its strength. Regardless, it’s interesting neither of these bellwethers is sending very clear signals at the moment.

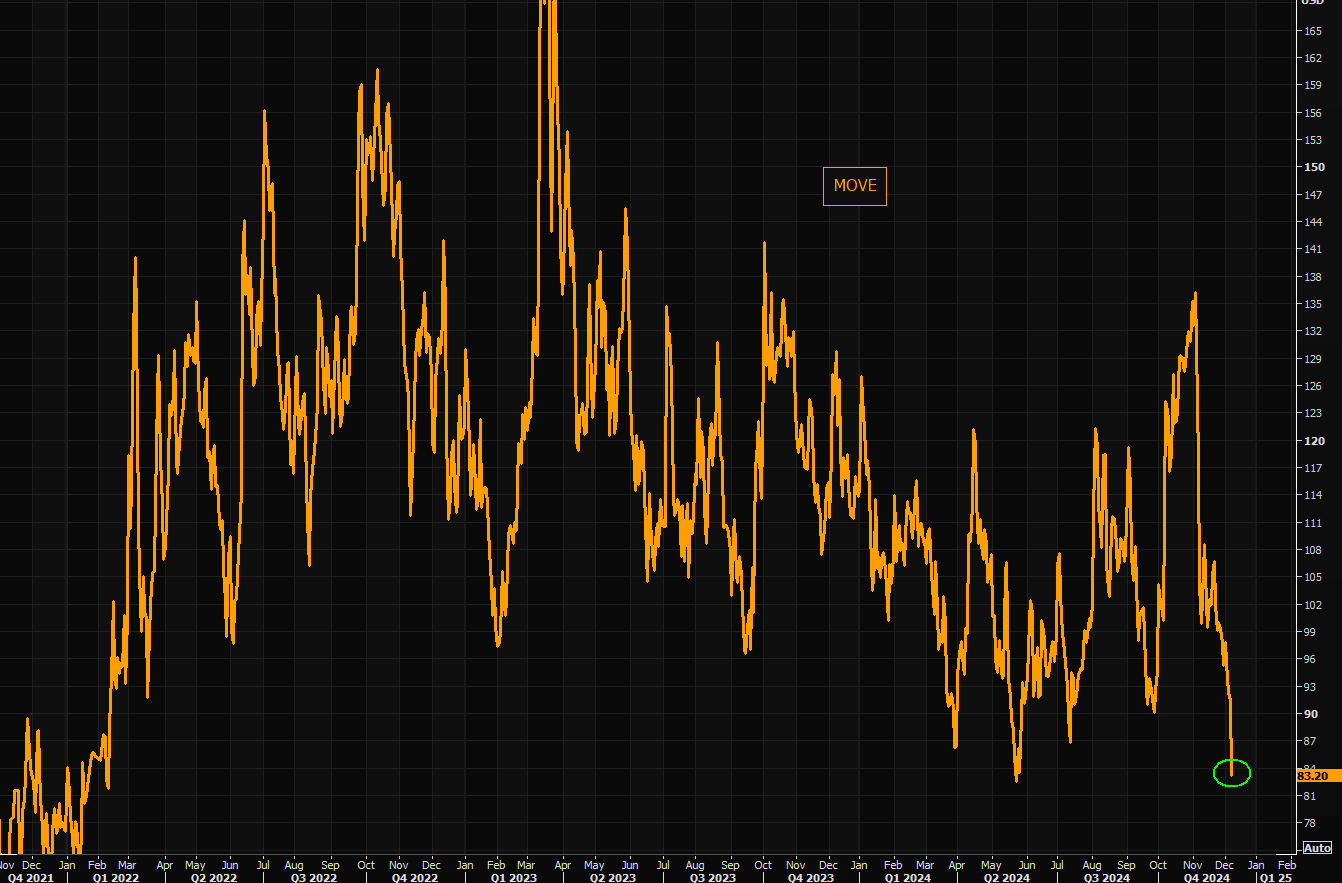

One of the most prominent trends since the election has been the momentous decline in volatility. There is normally some decline as the election itself is imbued with a degree of uncertainty. As the MOVE index of bond volatility shows, however, the decline has been dramatic:

The CPI report came out on Wednesday and was mostly in line with expectations, but still well above the targeted 2% level. Stocks rallied. The FT ($) headline captured the situation well: “US inflation uptick clears way for rate cut”. You truly cannot make this stuff up.

Finally, as I have often documented the increasing disconnect between market prices and fundamentals, I have also lamented the declining value of real investment analysis. This reality has also been showing up in the rapidly declining enrollment in the industry’s premier professional certification, the chartered financial analyst (CFA).

As the FT ($) graphs shows, test-takers this year will be less than half the peak in 2019. Some of this can be attributed to declining enrollment from China. Some, however, is also probably because it is easier to make money betting on meme coins than to learn difficult analytical skills.

Politics

With another week under our belt we have some more clues as to what the incoming Trump administration will look like. Spoiler alert: It’s not populist.

According to Axios, “Besides Trump, at least 11 billionaires will be serving in key roles in the administration.” Ed Luce ($) at the FT describes, “a new oligarchy is taking shape beneath our noses.”

On one hand, this is shaping up like many oligarchies where conflicts of interest are rife and leaders are not selected on merit. As Luce elaborates, “Around the court’s favourites are ever-widening rings of donors, hustlers, lobbyists, sycophants, and felons. Lots of felons.” While the point may be overstated, it is still well-taken.

This pattern of recruiting has prompted curiosity worldwide. As the Economist notes, “the word everyone was Googling was kakistocracy: the rule of the worst.” As a result, the magazine named “kakistocracy” the word of the year for 2024.

Another pattern that can be divined from Trump’s nominations thus far can be called “techno-libertarianism”. Rana Foroohar ($) describes in the FT , “The dream of a technology-driven world free from all governmental constraints has been around for at least as long as the internet has.” Peter Siegel ($) follows, “Musk is not the first person to think that the solution to what ails society is some kind of free-range polity unshackled from the burdens of fiat currencies, capital gains taxes and fluoridated water.”

Siegel goes on to highlight a major flaw with techno-libertarianism is that it doesn’t work:

What all previous efforts at a techno-libertarian utopia have in common is that they all failed except, perhaps, for Galt’s Gulch, which had the benefit of being fictitious. This is why most people stop fantasising about techno-libertarian utopias shortly after sophomore year intellectual history seminars on libertarian thought. It turns out that societies actually do need things like securities regulators, speed limits and garbage collection.

Jonah Goldberg ($) from the Dispatch responds similarly, but with more of a tilt to political philosophy:

To use language this crowd likes, liberal democracy is antifragile and scalable. It provides avenues and mechanisms for self-correction and adaptation. Yes, it can become sclerotic and dysfunctional, but the solutions—literally the solvents—that clear the arteries is liberal democracy itself. The hubris of the techno-monarchists or techno-oligarchs is that with the right technology, which was made possible by liberal democracy in the first place, you won’t need the system that made it possible. They point to China as proof I’m wrong. But I look to China as proof I’m right. Whatever problems we have, I’d rather have our problems than China’s.

Either way, the central tendency seems to be the same. As David Rothkopf summarizes for the FT ($): “with Trump’s billionaire inner circle we are seeing what could be the next phase in a consolidation of power among some of America’s richest citizens — one that has already seriously weakened US democracy. That is likely to get worse.” Yet, as Ed Luce ($) notes in regard to “The radically diverging foreign policy instincts of Trump’s picks,” he likes “his underlings to be at each other’s throats.”

So, the incoming Trump administration is sure not shaping up as a populist reform team and it seems to only be a matter of time before many of his voters come to realize this (I suspect this will feature prominently in the 2028 election). Yet, the potential for chaos and internecine warfare in the administration could easily undermine any initiatives, for better or worse. Hard to say what to root for. It doesn’t appear Jonah Goldberg’s suggestion of more but better liberal democracy is on the menu.

Geopolitics

The big news last weekend of the fall of Syria caught a lot of people by surprise. Ian Bremmer noted, for example, in the GzeroDaily newsletter, that Assad was unlikely to fall because “Iran and Russia are too invested in keeping him in power, so they'll absolutely jump in to save his bacon.”

While he was wrong with that call, he was absolutely right with the bigger call: The fact that the whole thing happened at all is further evidence of his “G-zero” thesis — the “breakdown in global leadership brought about by a decline of Western influence and the inability of other nations to fill the void” (as defined by wikipedia).

In the short-term, Turkey is probably the biggest winner and the US is a modest winner. Russia and Iran are the biggest losers. The decision to withdraw and/or withhold continued support for Syria indicates neither Russia nor Iran are in any kind of place right now to project power very far beyond their borders.

In the medium to longer-term, it’s hard to say if things will be better or not. As Bremmer notes, “Even countries that are happy to see Assad and Iran weakened, like Israel and Turkey, don’t want to deal with the chaos that his overthrow would leave behind.”

In short, a bad but fairly stable situation just became a very uncertain situation. The type of government that fills the void, whether it is better or worse than Assad, who will benefit, and whether there are ramifications for other geopolitical neighborhoods are all things that are “to be determined”.

Investment landscape I

One of the prominent investment themes over the last decade and a half has been the failure of active management, especially in relation to passive management. While there are a number of possible explanations for this, all of which are worth exploring in my opinion, Russell Clark ($) proposes a new one: Traditional macro analysis has failed because of the dominance of US technology firms.

Another feature of Western dominance and now mainly US dominance is a political system that allows the masters of new technology to assume political control. The ability to absorb the masters of new technology into the political system is underrated feature of the West- mainly because the existing old order bitterly resent it.

In the early days (back in the 1990s), a welcome was extended to tech firms in ways that encouraged their formation and development at the expense of incumbent competitors. Amazon, for example, was exempt from charging sales tax for years which produced a clear advantage over competitors with a physical presence. Later, social media companies were given an exceptionally light touch on regulations requiring authentication of minors, limits on using trademarked and copyrighted content, and publication of inappropriate material.

While the light touch approach facilitated massive growth and achievement of scale on a global basis, it also facilitated a number of social ills including the erosion of traditional media, increasing mental health problems among teens, increasingly polarized politics, and the spread of misinformation, among others. While affected members of society are increasingly pushing back against these ill effects, the political establishment seems to have little interest.

This creates an interesting compare and contrast exercise regarding technology and public policy with China, whose policies are very different:

For me [Clark], we are now at an interesting political, tech and macro crossroads. Chinese and US politics has diverged radically on tech. In the US, we have Elon Musk as best buddy to Trump, and big tech is close to big power. In China, they have chosen to regulate tech move heavily, and encourage far more competition.

As Russell Clark puts it, “Macro is a now a tech and political question”, which is surely right. I had thought people were ready to push back against the negative influences of Big Tech. While there are instances, by and large, Big Tech is still winning. It will be interesting to monitor how the US and China do in head to head competition on the issue of tech governance.

Investment landscape II

I have covered most of the material in this Substack post by Ann Pettifor before, but it provides a really good, succinct overview of some of the most important dynamics in the investment landscape today and is worth a read.

On one hand, she explains how “Too much money chasing too few income-generating assets causes asset wealth to inflate”. On the other, she explains, “Because the shadow banking system is so large (47% of global financial assets) and because it so interconnected with High St banks, its failure would bring down the global economy.”

This unsustainable system has not failed yet because the failure would be too consequential. As a result, governments bail out the major participants when push comes to shove.

So, I see three possible end games. One is the bail outs simply fail to work at some point and there is a big global crash. It’s happened before. Another is a period of lost decades, like Japan after its market peaked in 1989.

A final possible end game entails a change in politics. At some point, banks and shadow banks may lose sway with politicians and may no longer be favored for bailouts. At the same time, a change in national priorities may dictate the allocation of public funds be more sustainably redirected to industrial policy and national security rather than finance.

Investment landscape III

One of the more notable characteristics of this market is the attention placed on extremely risky assets assets like cryptocurrencies, meme stocks, and leveraged exchange-traded funds (ETFs). While most of these are effectively gambles, there are better and worse gambles.

For example, Dave Nadig higlights in a recent Substack one of the potential shortcomings of leveraged ETFs. Ideally, as Nadig writes, a leveraged ETF will employ a total return swap to produce the desired return profile. As he puts it, “The fund outsources both the leverage and desired beta in one transaction. It’s extremely efficient, and generally speaking the math works”.

However, total return swaps can’t always be used. For example, for funds that focus on Microstrategy, for example, the stock is so volatile there aren’t dealers willing to take on the risk of writing a total return swap in size. As a result, ETFs like MSTX and MSTU that leverage returns on Microstrategy rely instead on options. With options there are a lot more moving parts and a lot more ways to fail to produce the desired beta.

In the very specific instance of November 27th, for example, MSTR was up 9.94% and a 2x return would have been up 19.88%. MSTX actually returned 20.59% that day, but MSTU returned only 13.93%. As Nadig concludes, “That’s a problem. ETFs that try and mimic swaps don’t work reliably. They simply don’t.”

Investment landscape IV

In the midst of so much unusual market action, it at least helps to have some kind of mental model to visualize what is going on. Mike Green provides exactly this with a clever application of ChatGPT.

In general, what he does is establish some ground rules by defining traditional core asset classes. Then, he asks ChatGPT how the market is likely to evolve given the dynamics of both active and passive investing. In other words, “what would be the investment implications over the VERY long term?”

Given the parameters Green provided, ChatGPT responded that “US Equities would experience persistent upward pressure on prices” and “US equities would likely become overvalued relative to fundamentals”. Sounds familiar.

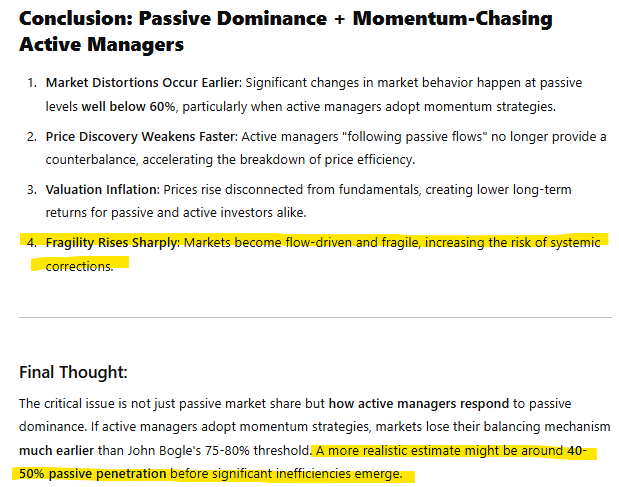

The main conclusion from Green’s exercise is that we are right at the threshold of where “market fragility rises sharply” and the “risk of systemic corrections” increases:

A secondary conclusion is there aren’t great places to hide. The same system that produces this fragility also causes small caps and emerging markets to underperform. Indeed, it’s the all-or-nothing nature of this market that makes it so fragile.

Implications

One way of trying to make sense of market action is to keep coming up with possible reasons for why stocks could go higher. This has always struck me more as an exercise of storytelling than thoughtful analysis, nonetheless, it is the more common way.

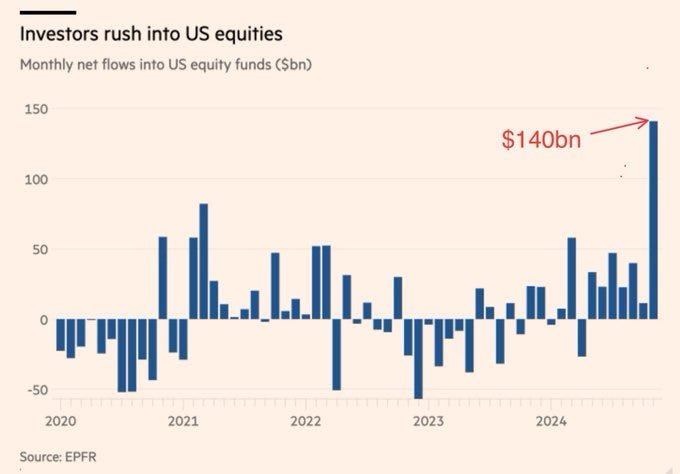

Another way is to step back and put things in perspective. At the beginning of the year there was little to suggest outstanding performance. Then the Mag 7 took off along with the artificial intelligence narrative. Then it became clear the Fed was going to cut rates and liquidity became the driver. Then everyone and their brother leveraged everything they had and put it into stocks. The culminating frenzy was stoked by the election after which retail investors poured a record-shattering $140B into stocks.

Jim Chanos provides some perspective on how a big a deal that $140B was:

To put the $140B monthly figure in context, it equals over 150% of the current US savings rate(4%) per month. And swamps the early-2021 SPAC/IPO/NFT peak.

These massive additions to stocks came while exposures were already at extreme highs. As Jim Biano notes, confidence about future stock returns is now almost literally off the chart:

So, on one hand these things did happen and go a long way in explaining the strong performance this year. On the other hand, none of these things were destined to happen nor did investors need to react the way they did. In short, the record of stocks in 2024 has been like a most amazing parlay bet on AI AND liquidity AND extreme exposure all happening.

Since December 4th, though, the S&P 500 has gone basically nowhere. Days would often start strong, but finish weak. It felt like the air was slowly leaking out.

The indications are piling up that we are very close to the end of the line for appreciation in the S&P 500 for the near-term. While it is understandable why more aggressive investors wouldn’t want to get off this train while it is still moving, it’s good to remember stocks can go down — and fast. Mike Green’s warning of fragility is no joke.

In the absence of new catalysts to drive stocks even higher — a new narrative, even more liquidity, or even extreme-er exposure, the odds are getting longer and longer against further material upside and shorter and shorter for a big decline.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.