Observations by David Robertson, 12/15/23

There was a Fed Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting week this week and this one was a doozy. Let’s dig in and figure out what it means …

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

By far the biggest news of the week was the FOMC meeting in which the Fed endorsed a pivot in rate strategy and is now much more comfortable with the prospect of lowering rates. The change in tone ignited a level of exuberance that superlatives can’t really do justice to.

The S&P 500 shot up 1%, the Russell 2000 rocketed up over 2.5%, and the 10-year Treasury yield fell over 15 bps. Notably, gold also jumped over 2.5% and DXY, the US dollar index, dropped over 40 cents. Many of those moves were even more extreme at the end of the meeting but faded into the close.

John Authers highlighted the dissonance between a modest improvement in data and the significant change in monetary policy stance: “Data of the last three months generally showed inflation slowing but remaining too high for comfort, and the labor market loosening a little but remaining tight. It’s difficult to see anything that should have changed the Fed’s governing narrative quite so much.”

This begs the question, “What was it that really caused the Fed to change its stance so starkly?” One possibility is an imminent problem - like a large, global bank. Alternatively, it could be signs of imminent recession. Another possibility is to pave the way for other central banks to start easing. Still another possibility is to loosen the reins on growth just as growth is beginning to slow (and in an election year to boot!). Of course, these possibilities are not mutually exclusive either; it could be any or all.

Regardless, monetary policy looks to be on a different track for the foreseeable future. In the meantime, market participants will be trying to figure out why, and in the process, determine how to position for the new landscape.

One of the more remarkable moves (of many!) has been the rapid decline in 10-year Treasury yields. Much of this has been due to the improving outlook on inflation and the change in monetary policy stance. These aren’t the only possible explanations, however.

Bob Elliott proffered another distinct possibility: “The treasury rally in the last few weeks was *not* retail driven. It was driven by demand from large asset holders rebalancing their portfolios from stocks to bonds, flows which pushed treasury yields unsustainably down, and likely to fade soon.” Good to keep in mind.

Economy

With so much of the economy riding on the consumer, credit trends have gained a lot of attention lately. The graph below from @SoberLook provide some useful perspective. Bottom line: The rapid rise in credit outstanding has been a function of inflation, not increasing indebtedness.

In other words, depictions of rising credit as an imminent threat to consumer spending are overstated. Yes, the cost of maintaining that debt is higher now. But the level of credit, adjusted for inflation, is just at its pre-pandemic level. While this certainly causes pain for some people, ultimately it is a good thing that consumer spending is becoming less dependent on credit growth and more dependent on income growth.

This dynamic captures a broader phenomenon in the economy. Growth is transitioning from being credit-based to being income and cash flow-based. This will take some getting used to, but ultimately it is a good thing. It also means credit-based economic indicators are likely to become progressively less useful.

Oil

Oil has continued to be an important story this year and broadly indicative of the commodity complex. While supply constraints are still supportive of a longer-term bullish thesis, a variety of shorter-term factors through the year has undermined oil prices.

Concerns about global demand, especially in China, have headlined the shorter-term factors. Weak support for production cuts by OPEC members has inserted additional uncertainty as well.

Less heralded, but just as important, however, has been ever-greater production from the US. As Rory Johnston reports ($), “North American total liquids production reached yet another all-time high in September of more than 29 MMbpd”. That growth was driven by the US which Johnston described as “gangbusters”. Apparently a decline in US oil production is like St. Augustine and chastity: We will get it, just not yet.

That raises a broader point with commodities in general. They are really hard to invest in. Oil this year has been a great example of that. It doesn’t mean one shouldn’t avoid commodities altogether, but it definitely means one should be careful in doing so.

Monetary policy I

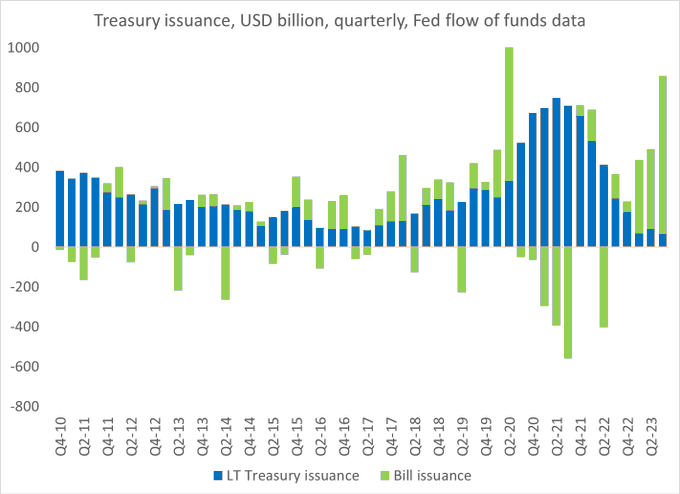

One of the more important phenomena this year has been the disproportionate issuance of Treasury bills (as opposed to longer-term bonds). Brad Setser illustrates beautifully the change in issuance pattern:

The unusually high bill issuance has also coincided with unusually strong stock performance over the last year or so. Combine that observation with the Treasury’s decision to notch down the issuance of coupons relative to expectations in the latest refunding announcement and it starts looking like an intentional effort to boost the market.

That may be, but it also may not. What other reasons could the Treasury have? Just for kicks, let’s assume the Treasury wants to throw out a lot of bills because it wants to drain the reverse repo facility (RRP) at the Fed. This would serve two purposes. One, it would eliminate the remaining evidence of gross over-indulgence by the Fed in buying Treasuries during the pandemic. Two, it would unlock the liquidity sequestered in the RRP and free it to do things like buying stuff - and investing in Treasury bonds.

Given the potential for the economy to slow down next year, and for Treasury issuance to remain high, this could be a very useful dynamic to have in place. Hmmm, what if this is a plan coming together? If so, it would suggest some combination of higher incremental demand for Treasury bonds (which would be good) and higher than expected inflation. Let’s see.

Monetary policy II

The peculiar market divide on the rate outlook ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/63a4e0ca-ae62-4b35-be18-d27afe4210f8

A disagreement has emerged over the interest rates that the Fed will set in 2024. The more investors disregard the signals emitted by the world’s most influential central bank, the more likely they will find themselves on the losing side of this debate.

The third explanation centres on the Fed’s loss of credibility. This is due to its mischaracterisation of inflation, delayed policy measures, supervisory lapses, poor communication, repeated forecasting errors, questions over the trading of some officials and weak accountability.

The first point El-Erian makes is market expectations for rate cuts are significantly out of line with the Fed’s communications. While those expectations seemed a lot more unrealistic when the article posted last Saturday, there remains a large gap. El-Erian warns, “To avoid another potential setback, investors should either prepare for the possibility of higher yields in 2024 or adjust stock valuations accordingly.”

It is also interesting that El-Erian goes on to provide a laundry list of the Fed’s failings over the last few years. He is never one to shy away from criticizing the Fed (nor does he mind insinuating how he would be a much better Fed chair), but his accusations still pack a punch. For one, they are all true, and for another, they really do paint an ugly picture for Fed credibility.

This isn’t a big problem today or tomorrow. At some point down the road, however, there is a good chance it will be. Just like reputations, credibility takes a long time to build up but can be demolished in a flash. Given the Fed’s already crumbly foundation of credibility, it may not take much of a challenge to knock it all down when the time comes.

Investment landscape I

One of the more surprising phenomena of 2023 has been the continued strength of the stock market. While I expected the Fed to continue pushing rates up, I would have thought the consequences of higher rates would have filtered down into stocks by now.

A number of reasons exist for the unusually strong performance. The rollout of ChatGPT initiated a rush of enthusiasm for artificial intelligence. The Treasury has been issuing a disproportionately large share of bills versus bonds. In addition, deficit spending has continued at a brisk pace.

Yet another reason, however, has been the increasing weight of investment strategies that sell options in order to generate income. The evidence of this was illustrated in an informative thread by the colorfully named Dr_Gingerballs:

Here is a look at what happened to the dispersion from the bottom in Oct to now. As you can see, it was still a bifurcated market. For the most part, the shape of the spectrum was maintained and just shifted upward. This shows that the market largely moved together as a unit.

While I wouldn’t call this definitive proof, it is strong circumstantial evidence that the market is being driven higher by a systemic force. In this case, it appears the burgeoning practice of selling volatility is driving stocks. In contrast, it is not higher earnings expectations or other fundamental reasons.

I like this analysis for three reasons. First, it corroborates a smattering of other indications of volatility selling and its effects. As such, it reveals stock performance as importantly dependent on the continued ability and intention to keep volatility suppressed. Finally, it is yet another example of someone from outside of the finance industry providing interesting perspective by way of cross-disciplinary insights. Nice!

Investment landscape II

The Japanese yen has been getting a lot of attention lately. Over the last month it has gotten stronger against the US dollar and has demonstrated a couple of strong bursts in doing so.

As I have mentioned, this is potentially important because there are a lot of Japanese savings invested abroad and if/when that money gets repatriated back to Japan it will affect capital markets worldwide. Felix Zulauf recently laid out the scene in a Grant Williams podcast …

THE GRANT WILLIAMS PODCAST: Episode 68, Felix Zulauf, DECEMBER 06, 2023 ($)

https://www.grant-williams.com/podcast/felix-zulauf-2023/

Capital flows is really the key to Japan because the Japanese yen is the most undervalued currency in the world, and as long as the Bank of Japan does not change policy, the yen will remain weak.

If they are serious and want to bring down inflation to 1% again for the long-term, they have to tighten monetary policy. If they tighten monetary policy, the yen will fly. The yen would fly. Whenever that happens, with the huge positioning out there, the yen has been the most attractive funding currency by everybody in the world. So the whole world is short yen and once that changes, then you have a big move.

One of Zulauf’s interesting comments is “the whole world is short yen”. So, the yen matters partly because of positioning. Indeed, this is so pervasive as to be a foundational aspect of the investment landscape. Change that positioning and a lot of other things get upended. All the tailwinds of capital flows that make capital cheaper than it otherwise would be get reversed.

Bob Elliott also provides some color on Japan. He doesn’t expect “a quick shift to tightening” because “The macro dynamics just don't support it”. Fair enough, and good perspective. Nonetheless, US Treasuries continue to rally and the yen continues to strengthen. Is this just a coincidence or is the issue being forced on Japan?

Investment advisory

Investment culture is rife with various forms of narrative that present individual investors as unsophisticated plebs badly in need of the resources and sophistication of institutional advisors. The reality is much grayer. While a lot of retail investors do make preventable mistakes, many are extremely capable of analyzing data and making good decisions in the context of uncertainty. Conversely, far too many advisors prove themselves to be neither sophisticated nor adept at leveraging resources to improve client outcomes.

I was reminded of this paradox when Almost Daily Grant’s (Friday, December 8, 2023) captured the latest thinking of Citi Global Wealth chief investment officer David Bailin:

I’m not sure what investors are waiting for … The U.S. economy is going to stay strong and, eventually, money market rates are going to come down, so why are people not buying core 60/40 portfolios?

The possible answers to Bailin’s question are plentiful. Maybe they don’t trust the reasoning. How can one be so sure the economy is going to stay strong? How can one be so sure money market rates are going to come down? How can one be so sure a core 60/40 portfolio is the best investment strategy right now? The answer, of course, is you can’t be that certain.

In addition, people may not trust the approach. It sounds a lot more like a plea from an underperforming salesperson than it does helpful investment advice. It also sounds like performance chasing - after one of the best months in history for the 60/40 strategy. Further, people may not trust Citigroup, which has repeatedly demonstrated its capacity to shun prudence at the worst possible time and put clients and investors at risk in doing so. The echoes of Chuck Prince are almost audible.

Perhaps too, it’s just crappy advice. Stocks are near record valuations. Bonds look better, but don’t compensate for risks relative to cash returns. The 60/40 strategy had a great run but it’s becoming increasingly clear that run was a historical anomaly. Now it’s time to move on.

And this is the bigger issue. There is so much room for the investment industry to do better. To date, though, there has been little effort to tackle the big underlying problems - such as repeatedly pawning off the same old tired advice and focusing almost exclusively on gathering assets. It’s time for the industry to move on too.

Implications

As I noted earlier, the FOMC meeting this week highlighted a fairly significant change in policy direction, not just for monetary policy but more broadly for the Biden administration. Namely, it appears the Yellen faction is winning out relative to the Sullivan faction, at least for the time being. This has significant implications for investors.

First and foremost, there will be greater emphasis on liquidity and growth at the expense of geopolitical advantage and national security. This is likely to pave the way for better growth, in the US and globally, but will come at the expense of a weaker US dollar and probably bigger geopolitical problems down the road. A weaker dollar would suggest more expensive commodities, all else equal.

One thing to keep in mind is the shape of the yield curve is likely to be an increasing important issue. With lots of banks still holding underwater long-term Treasuries, it will be important for their financial health to have an upward sloping yield curve. This means long rates higher than short rates. As a result, it is not fair to expect long rates to go down in lockstep with short rates.

Another thing to keep in mind is moral hazard. As we’ve seen too many times before, when lots of liquidity is sloshing around, quality doesn’t matter much, if at all. As a result, while improved liquidity is likely to help legitimate businesses, it is fair to expect quite a bit of speculative activity as well.

Finally, it is important to keep a couple of other things in mind as well. First, the move in 10-year Treasury yields has been breathtaking. Given their importance to asset valuations everywhere, this is not a good thing. The speed and amplitude of recent moves serves as a warning light for just how fragile the valuations of risk assets currently are.

Second, not only does this new push to ease financial conditions embrace moral hazard, it is also pre-emptive, i.e., it breaks the normal policy mode of responding to a problem. This pre-emptiveness also makes policy more unpredictable. As a result, this new policy direction is playing with fire. It might work to transition the economy into a more productive mode, but it also risks being both counterproductive and destabilizing.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.