Observations by David Robertson, 12/22/23

As a programming note, I will be off next week and return with the Outlook edition on January 5. Until then, Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays!

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

Jerome Powell ignited a year-end bacchanal in markets the last week with his dovish comments in the FOMC meeting. While this has manifested most apparently in speculative stocks, the fun has been widespread.

Flows have been exceptionally strong. Themarketear.com ($) reports, “Huge monthly inflows in SPY on the back of the dovish FOMC meeting. We last saw such inflows in 2007.”

Almost Daily Grants (December 18, 2023) follows up with a similar report: “Investors and analysts alike, meanwhile, have responded to the rally by ramping up their exposure. Domestic equity funds gathered a net $25.9 billion in assets over the seven days through last Wednesday per data from EPFR Global, marking the ninth straight week of inflows for the longest such streak in nearly two years.”

At the same time, the US dollar has weakened while gold has gotten stronger - suggesting the potential for dollar debasement has been an important force. In addition, lest we lose track, the damage from higher rates continues to accumulate. Bankruptcies are rising and commercial real estate is crumbling, and there are several signs of emerging consumer weakness.

For now, these inconveniences remain as a dull hum in the narrative background. It sure wouldn’t take much to tip the scales in the other direction, however. As a result, as positive as things seem for the market right now, they remain in a fragile balance that can be upset easily.

That fragile balance was on display Wednesday afternoon. As themarketear.com reports:

1 week gone in 120 minutes..."Between 2:00 and 4:00 PM ET today, the S&P 500 erased ~$600 billion of market cap. To put this in perspective, the S&P 500 added ~$600 billion of market cap over the last week. The index was up for 10 straight days but erased 5 of those daily gains in 2 hours."

Sure, it’s just one day. The interesting thing though, is nobody is very clear on what caused it. That’s the problem with fragility; there doesn’t even need to be a “cause” per se.

Geopolitics

https://twitter.com/michaelxpettis/status/1736256970829824245

The result [of China's shifting of domestic investment out of the property sector and into manufacturing] will be that those economies who are slowest to take action will see the most rapid decline in their manufacturing. That is why I think a worsening of global trade tensions is almost inevitable. Expect tempers to get much worse in the next 3-5 years.

As it becomes increasingly clear that the deflation of China’s real estate bubble will take a long time to resolve, the seriousness of public policy responses is also ratcheting up. In very broad terms, the shift seems to be in the direction of investing in the manufacturing sector, as opposed to the real estate sector.

While understandable in many ways, this new direction comes with a couple of significant drawbacks that are likely to undermine its effectiveness. One is that it continues to pursue policy initiatives that address supply rather than demand. Until demand from Chinese consumers increases at a sustainable rate, it is unfair to expect economic growth to improve on a sustainable basis. Until public policy responses address deficient demand (as opposed to supply), there is no good reason to expect consumers to increase spending.

Relatedly, if China is just going to continue to overproduce stuff, that stuff will have to go somewhere else, i.e., get exported. With other countries contending with their own consumer demand challenges, it is unlikely those exports will be welcome. As a result, Chinese policy is likely to rub a lot of trade partners the wrong way.

It is possible China is weighing the pros and cons and making a bet that some countries will not have the political wherewithal to stanch its flood of exports, or at least not in a timely way. Sooner or later, however, the persistent effort to tap consumer demand from other countries is likely to evoke political retribution. As Pettis concludes in regard to global trade, “Expect tempers to get much worse in the next 3-5 years”.

Politics

As the political environment in the US has become increasingly problematic over the years, it has been easy to focus on the low quality of political leadership. As true as that is, it also deflects blame from the populace. The evidence suggests there is plenty of blame to go around: People increasingly have unrealistic expectations.

In the realm of investments, a recent graph posted by @SoberLook reveals US investors not only have the highest expectations for long-term portfolio returns in the world, but their returns also exceed those of financial professionals by the widest gap in the world.

This creates an unfortunate political dilemma for politicians: Either you pull all the stops and sacrifice the long-term in order to meet unrealistic expectations in the short-term, or you fail to meet short-term expectations and get voted out of office. It’s not actually a hard decision.

Regardless of how unfair this may be, voters don’t care. The same type of misplaced expectations appears elsewhere as well. Jim Bianco highlighted poll results regarding price controls. While price controls are considerably more popular among Democrats, a majority of people all across the political spectrum favor them.

It doesn’t take much economics or much history to realize price controls are a much more appealing as a political idea than an effective policy suggestion. As Bianco summarizes, “the proven way to ruin an economy is what the majority now wants. This too speaks to the political mood; people want immediate results and don’t particularly want to think about the consequences.

To that point, a bunch of feathers got ruffled a few weeks ago when President Biden posted on the subject of inflation:

Let me be clear to any corporation that hasn’t brought their prices back down even as inflation has come down: It’s time to stop the price gouging. Give American consumers a break.

Large swaths of the “cognoscenti” were offended by the “economic ignorance” of the statement and set immediately to correct the record and impugn Biden’s intellectual capacity.

Now, I’m no huge fan of Biden, but I think he understands something the “cognoscenti” doesn’t: the political center of gravity of the country doesn’t want to hear textbook economics and doesn’t trust it anyway. People want what they want and don’t want to hear excuses for why they can’t have it. While this is miles away from the ideal of representative democracy, it is the reality. There are no easy answers and politics is simply reflective of that.

Investment landscape I

Manny Roman: ‘there will be a tidal wave of money coming’ ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/626d794e-be2e-4509-b401-bdffec2e0d6a

Unhedged: On the day the Fed starts to loosen policy, what changes? What is Pimco’s strategy in anticipation of that day?

Roman: Well, the first thing is, of course, we will own more duration. Right now we are duration neutral. And I think there will be a tidal wave of money coming. Right now you have $5tn in short-term cash in the US, rolling Treasury bills, that can extend in duration and take more risk. It is very hard to predict when, because it’s animal spirits, and predicting animal spirits is not an easy game.

One of the key themes in terms of market forces the last several years has been liquidity. When liquidity goes up, stocks go up. That’s why the Fed’s indications on interest rate policy are followed so closely - they are taken as guides to future liquidity.

Guidance on rates is also something else though - it is also guidance on asset allocation decisions. Short-term rates in the 5+% range are very attractive when inflation is in the low-single digit range and falling. When those short-term rates become lower, other, riskier assets start looking better.

This is exactly what Manny Roman is highlighting. The $5+ trillion in money market funds is a lot of money that is hanging out there because it is relatively attractive to do so. Not all of it is mobile, but enough of it to matter is. When it becomes relatively less attractive to hang out and earn short-term interest rates, the owners of those funds will redistribute them in other more attractive assets.

The “What” and the “When” will be big questions for 2024. As to the “What”, recession risks will likely impede the path to cyclicals and commodities for some period of time. That would probably keep the Magnificent 7 and speculative stocks as primary recipients of reallocated dollars until either the economic outlook improves, inflation turns higher, or both.

As to the “When”, Roman was right when he said, “predicting animal spirits is not an easy game”.

Investment landscape II

One of the phenomena I have highlighted frequently is the unusual confluence of factors that have contributed to low inflation from the mid-1990s through the pandemic. These include globalization, aging populations, and high levels of debt. As debt has become untenably high and trade is becoming more constrained, many of the tailwinds that suppressed inflation are now reversing.

One of the big factors in that process, and one that is also due to change directions in the not-too-distant future, is Japan. Having built up massive debts in the real estate and stock bubble of the late 1980s and early 1990s, Japan has been forestalling the consequences ever since. It has done so through persistently loose monetary policy and yield curve control.

The dearth of yield available for Japanese investors has forced them to search abroad and in doing so, has suppressed yields worldwide. As such, negative interest rates in Japan and a smattering of Japanese money in foreign capital markets can be considered among the last vestiges of the neoliberal geopolitical order.

This history is important to understand for at least two reasons. For one, the piles of Japanese money that went abroad in search of yield created incremental demand for foreign stocks and bonds and therefore boosted prices. When that money eventually gets repatriated, the opposite will happen. Because this has been going on for so long, it will feel very different and oddly deleterious to risk assets.

For another, this is a decision and a phenomenon that will originate outside of the US. As a result, undue focus on domestic affairs could create a big blind spot.

Investment advisory

Markets are becoming less efficient, not more, says AQR’s Clifford Asness ($), h/t @biancoresearch

https://www.ft.com/content/813b3d76-6ef1-427d-a2e0-76540f58a510

“I probably think markets are more efficient than the average person does, long-term efficient, but I think they are probably less efficient than I thought 25 years ago,” Asness said in an interview with the Financial Times. “And they’ve probably gotten less efficient over my career.”

However, Asness said that the availability of more data was actually making things harder for most investors, whether they were individuals trading at home or investment professionals at a large financial institution, and compared the belief that more information would make markets more efficient with early optimism about the impact of social media.

It says something that a person like Cliff Asness, who hails from the ideological center of the universe for efficient market theory, is making concessions about efficient market theory. Importantly too, he believes markets have gotten less efficient over his career.

This observation (from someone who really knows his stuff) stands out for two big reasons. First, it highlights the role passive funds have played in making markets less efficient. As passive investing has grown, it has displaced active investing. With fewer actively managed assets, the forces to incorporate new information into prices becomes weaker. Worse, prices become progressively more influenced by asset flows and progressively less influenced by fundamental information.

Second, Asness’ observation highlights the role of information in investing. Many people, especially when new to investing, assume “the ubiquity and immediacy of all information” inherently makes markets more efficient. Somewhat unintuitively, however, the availability of more data is “actually making things harder for most investors”.

Reading between the lines a bit, the name of the game is not so much the accessibility of information, but the processing of it. There are a lot of good information sources and analysts of specialized topics. Arguably too many. In this sense, focusing on information is like scrolling through social media; you get lots of interesting tidbits, but you never “arrive” at your destination.

Processing information, on the other hand, is a different type of endeavor. It takes experience, knowledge, and effort to filter, curate, analyze, and integrate information into a cohesive viewpoint. Above all, it takes discipline. It also takes a cohesive viewpoint in order to have enough confidence to act when it is advantageous to do so, and to refrain from acting when it is not.

Consequently, the market works very differently than a lot of people seem to think. The notion that more information leads to more efficient markets is about as accurate as the notion “social media makes us like each other more”. In other words, it doesn’t, not even remotely. This will create opportunities for those who can see through the information narrative and manage accordingly.

Implications

The hangover from the FOMC’s party last week has yet to arrive as the markets are still drunk. A continued upward bias seems to be the path of least resistance for risk assets into the new year.

At some point there will need to be a sober reassessment. The weakness in the US dollar and the strength in gold already suggest there will be bumps along the way next year. Earnings announcements in January are also likely to bear witness to the prolonged effects of higher interest rates. Add in a debt ceiling sequel, a presidential election, and some geopolitical flare-ups and there is distinct potential for some turbulence.

While I have discussed the diminishing role of the Fed over the last year, I think that issue could take center stage next year. Although deficit spending and Treasury management have usurped the Fed in terms of practical influence on the economy, investors are still clearly taking their cues from the Fed. I suspect the belief in the Fed’s ability to dictate economic direction will be sorely tested.

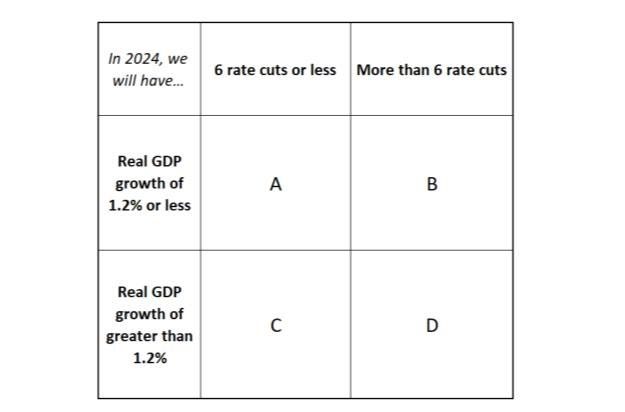

The model below outlined by Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu in their Unhedged letter helps to understand why. They suggest boxes A and D are unlikely which seems reasonable. It would be problematic for all kinds of reasons to have realized monetary policy completely out of sync with economic activity.

So, boxes B and C look most likely. In the event of very low GDP growth, markets will respond favorably only if those incremental cuts actually provide stimulus. Companies that will be in the most trouble will be those who need to refinance at significantly higher rates than they locked in during the pandemic or before. A couple of rate cuts ain’t gonna help.

Alternatively, if economic growth continues plugging along at a pretty good pace, rate cuts are not going to be the issue, surging inflation is. This will especially be the case if gas or food prices pop up during the year. I doubt the Fed will have much leeway to lower rates if inflation is rising in an election year.

The bottom line is 2024 is likely to be the first time in a very long time the Fed will be forced to make a difficult decision. When that happens, it will also become clear the Fed cannot just magically make good things happen. When that happens, the narrative of the omnipotent Fed will dissolve very quickly. When that happens, there will be considerably less support for extreme valuations.

In the meantime, long-term investors are caught in something of a catch-22. While most of the appreciation has occurred in the more speculative corners of the market, just about everything has gone up. That makes entry points for interesting longer-term exposures such as manufacturing, gold, and commodities less attractive than they were. In an age of fairly intense government intervention and excess liquidity, this is likely to remain the case for the foreseeable future.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.