Observations by David Robertson, 1/24/25

The starting gun sounded and now we are off to the races taking in all of the changes the new Trump administration is making and trying to make sense of it. Let’s dig in.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

One of the more notable moves following the inauguration was a big drop in the US dollar (USD). It’s also pretty clear the decision to push back tariff increases was a major cause of the move. Given the notable strengthening of USD since the election, however, there was probably some element of give-back when the news was less onerous than the expectation.

The decision, along with the market reaction, invite a number of questions. Was the Trump administration worried about disrupting markets too much? Is this an early signal that there will be a lot more “bark” than “bite” to policy proposals? Will markets serve to keep more outlandish policy proposals in check? Regardless, this was an interesting start.

Normally when I see headlines like, “Companies should step off the quarterly report treadmill,” which I recently did in the FT ($), I tend to skip right past the plea because it’s almost certain to be ineffectual. However, when I notice the statement comes from the CEO of Norges Bank Investment Management, I take notice. Not only is Norges one of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world, and therefore a significant owner of stocks across the globe, but it is also a thought (and practice) leader on governance issues.

The effort is not to reduce transparency but to promote “a more thoughtful approach to corporate reporting that encourages companies to focus on sustainable value creation. This means fewer but higher-quality reports that provide genuine insight into a company’s strategy and prospects.” Who knows if this effort by Norges will have much effect on corporate reporting practices or not, but it’s nice to see the endorsement from a very credible source.

Politics and public policy

Well, we got the inauguration, the inaugural speech, and a number of executive orders on Monday a number of releases since, and a presentation to Davos. The overwhelming sense I have gotten is “Where’s the beef?” The most substantive policy issues like tariffs have been pushed back and the issues getting the most attention are those of a personal and/or petty nature.

What have we learned so far? I would argue very little. To highlight Panama as an overarching geopolitical concern, with barely any mention of China, is deeply unserious. So is declaring lower oil prices and lower interest rates. But then, we already knew this.

On January 16th, Brad Setser presciently noted, “Reading between the lines, the disagreements on the nature of the tariffs (across the board or somewhat targeted) among the incoming Trump team could be a signal that nothing concrete will be announced on day 1.” Nice call Brad! So internal disagreements may be an important constraint on policy implementation.

Based upon the (admittedly little) evidence thus far, it’s not going to be very useful to follow the details of policy because they are too uncertain. This assessment is corroborated by Peter Siegel ($) in his commentary for the FT. He noted, “one thing I learned [from covering the first Trump administration] is that making forecasts about what he [Trump] will do as president is a fool’s errand. He’s just too unpredictable, and what he says one day can become a policy that goes in the polar opposite direction the next.”

This means it is more useful to consider the big picture landscape and Jonah Goldberg ($) provided some nice perspective back in December. He distinguished politics from governance by highlighting, “Government isn’t a thrill ride”:

There’s much more room for drama, entertainment, and excitement in campaigns and TV studios. Ultimately, though, government is supposed to operate differently than politics. But government cannot be safe, stable, and predictable indefinitely if our politics are bottomlessly crazy. If you have become addicted to politics as a form of entertainment, eventually you’ll treat government as a form of entertainment, too.

He then goes on to describe why this is not a harmless exercise:

People like roller coasters and merry-go-rounds, not to mention haunted houses, moon bounces, etc., because they take it on faith that they are safe. The engineers and architects who create amusement parks can curate a feeling of childlike joy—fun for children of all ages!—precisely because people trust that everything works the way it’s supposed to. They take it for granted that the garden-like—and wildly overpriced—microcosm of the amusement park is stable, safe, and sturdy …

But when it comes to our federal government right now, too many people are behaving like the system is stable and safe enough that they can afford to be clowns in the parade.

I think this captures a really important phenomenon in our politics and across society: We have lost our sense of risk. There are so many bad decisions and so much bad behavior that goes unpunished that we start believing there is no such thing as punishment.

This belief system has been amplified by demographic and socio-economic factors. The Baby Boom generation has stood out for its relentless embrace of risk-taking. In addition, while younger generations are taking less risk in their personal lives, their outlook for getting ahead is so bleak that taking ridiculous financial risks is often perceived as the only way out.

As a result, it seems as if we are living an experiment that is going to test the structural integrity of our markets, our economy, our government, and our society. And the only way you really know where limits are is to exceed them and realize the consequences.

At the same time, though, not everyone enjoys “bottomlessly crazy” and not everyone wants to be entertained by their government. Some people prefer quiet and reliable. When confronted with “politics as a form of entertainment”, they just tune it out. Some people enjoy “bottomlessly crazy” right up until the point they suffer the consequences. This suggests there are practical limits to political action. Awareness of this reality may help explain the delay in some of the more impactful policies such as tariffs.

However, while caution and discipline are useful in preventing the worst excesses, they are imbued with a risk of their own. Siegel continues:

The one overarching, contrarian prediction I will make, however, is that Trump will suffer from his lame duck status far sooner than many people anticipate. Second presidential terms are notoriously messy affairs … But for second-term presidents, each following day is one day closer to political irrelevance.

This presents an interesting way to frame the potential impact of the Trump administration. The longer major initiatives are pushed back and the more political capital erodes or even reverses, the faster political irrelevance will arrive. For all the Sturm und Drang of the early days, there is a very limited window of opportunity to change things.

Investment landscape I

Slimming Down a Top-Heavy Market

https://www.hussmanfunds.com/research/rs250115/

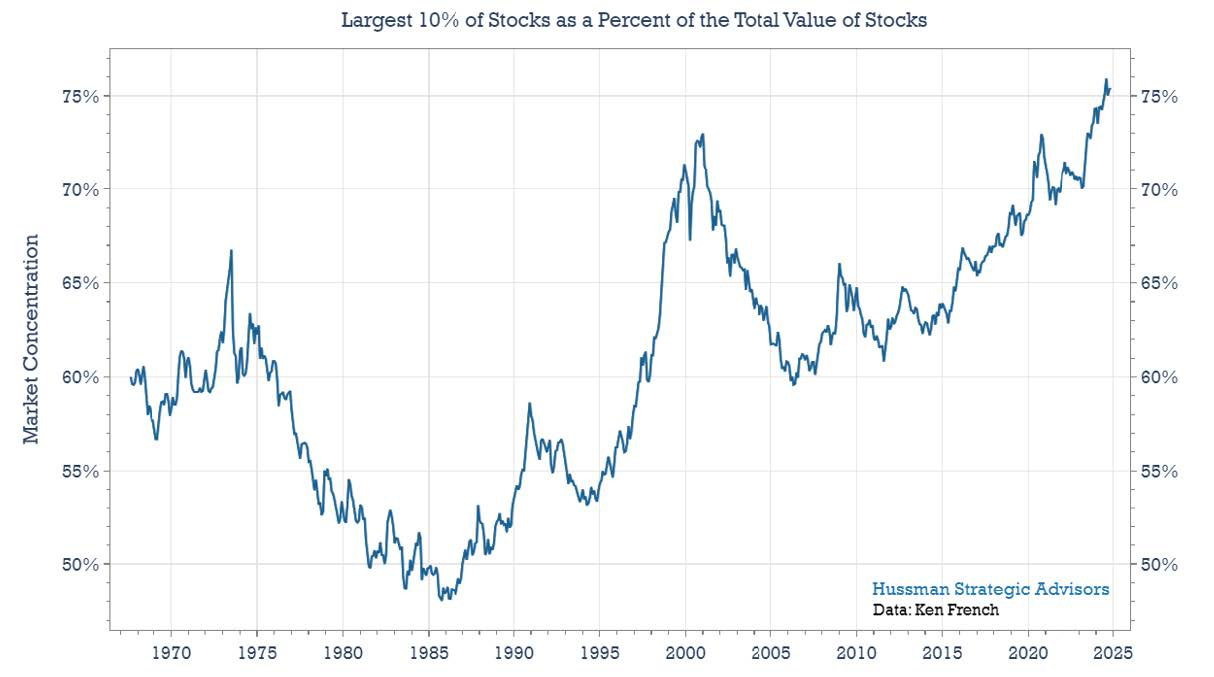

Over the past five and a half decades, there have been two previous peaks in market concentration: one in 1973 and another in 2000. Today, market concentration has reached an all-time high – and while not shown here, is even higher than levels seen in the early 1930’s.

Bill Hester of Hussman Funds makes a number of useful observations in this piece. First and foremost, high market concentration tends to correlate well with market peaks. As a result, concentration can serve as a useful indicator. Given current record highs in concentration, investors should be aware of heightened market risk.

Even though Mega Cap stocks tend to underperform in subsequent periods of peak concentration, the relative performance of Non-Mega Cap stocks is nuanced. For one, “Following periods of high market concentration both Mega Cap and Non-Mega Cap stocks have historically tended to have either very low returns, or losses, over the next decade.” For another, “the broader historical record suggests Non-Mega Cap stocks can also be riskier than Mega Cap stocks in the midst of a panic.”

Finally, post-peak concentration periods are marred not just by low returns, but by higher volatility. Not a good combination.

Interestingly, Mike Green picks up on the very same phenomenon in his recent Substack post:

Surprise, surprise, surprise… Now we get similar correlation breakdowns, albeit lower in magnitude, in the late 1920s, the 1966 peak, the 2000 peak, the 2021 peak, and today (the mother of all correlation breakdowns). Again, this is a reminder that these portfolios comprise identical stocks! Can we explain the breakdowns? Yes, it is indeed tied to concentration

Green goes on to argue that not only are the correlation breakdowns associated with market peaks related to concentration, but that concentration is related to passive flows: “So we have a theoretical mechanism via Jiang and Haddad by which passive flows cause the largest stocks to increasingly deviate from the rest of the market, [and] the empirical results show the same”. In short, we have the “What” and the “Why”.

Portfolio strategy

While investors have been regaling in big stock gains, there has been radio silence on the performance of bonds. As Jim Bianco shows, the reason is performance has been dismal.

The last 3 years have been the worst stretch for bonds in 180 years (no typo)! Yes, this has led many to violently oppose the bond market.

As Bianco suggests, part of the strength in stocks may very well be due to the unappealing option bonds have presented. As Bianco also suggests, it may not take a whole lot more in additional yield on bonds for investors to be incentivized to shift allocations in favor of bonds.

In addition, public policy considerations are also likely to play a role. As budget deficits continue apace, the Treasury will need to keep issuing debt. In order to ensure sufficient demand, either bond yields will need to be high enough to be compelling relative to stocks or stocks will need to sell off enough to make the safety of bonds look more attractive. These conditions can occur organically or they can be nudged by policy decisions. The next few months should give us some clues.

Culture

I continue to be amazed at the number of smart people I follow who seem to think the Trump administration is going to usher in some kind of new era of immense prosperity. It reminds me of being amazed at the number of smart people I follow who seemed to think the Biden administration was going to usher in some kind of new era of immense prosperity. Regardless of your political “team”, there just aren’t any silver bullets here.

It is in this context that I found Ben Hunt’s recent piece especially insightful:

I think we had a death in the American family over the past few days, and with it the death of the America-unifying idea. I think the office of the President of the United States — the personification of the idea that there is a shared meaning in being an American — is now dead.

It was Biden’s ‘pre-emptive’ pardons and ‘declarations’ of Constitutional amendments. It was Trump’s ‘executive orders’ on Tik-Tok and ‘issuance’ of memecoins. Two parties. Two Presidents. One single oligarchic, self-serving, rules-for-thee-but-not-for-me, Hunger Games death rattle of a 235-year-old institution.

I am now certain that there is zero hope for the unifying idea of America that I grew up with … it’s every American for themselves now. It’s the only move we’ve got … I no longer believe there is a natural, organic and effortless idea of the United States of America that supports that community, and that’s a really hard thing for me to say.

Strong words for sure, but also words that explain quite a few things. Why have so many people been holding out so much hope that a single person will be able to turn their lives around — if not for the desperate and irrational hope of resurrecting something that no longer exists? Why have so many people placed so much hope in Trump and Biden when neither of them are the most capable people of leading the country? They are the choices we got, but they weren’t good choices.

It seems like Hunt is on to something — maybe it’s the loss of “the unifying idea of America,” maybe it’s the loss of the “American Dream,” or maybe it’s just a more general sense of loss for the way things were. Regardless, the sense of loss explains a lot of behavior.

This presents an interesting possibility. Perhaps our politics is simply reflecting a grieving process for the loss of American might and prestige. Some are in denial of this loss and choose instead to believe whacky and improbable theories. Others are just angry. Both represent early stages of grieving.

Insofar as this is correct, there are a couple of important implications. One is that there is a lot of cope going on that is masquerading as policy. While time is probably needed to work through the grieving process, it is also time wasted in addressing many of the country’s most pressing challenges. The costs of putting things off is escalating rapidly.

Another implication is we are in the relatively early stages of this process. If denial and anger are the prominent modes now, we haven’t even started into bargaining or depression. This suggests things will get worse before getting better and that it is going to take time; it’s a process.

Finally, while the market has mainly been able to take politics in stride, it is still heavily dependent on the assumption of US exceptionalism in its many forms. Just as soon as investors start seriously questioning this exceptionalism, there is a risk of a very significant change in narrative, and probably some very messy politics.

Implications

With an eventful week of pronouncements and executive orders, it is easy to be overwhelmed trying to determine the implications of each. This is a shame because it often leads to analytical whiplash and ultimately bears little fruit.

For better and worse, the impact of policy is becoming increasingly constrained by real economic, financial, and political conditions. The good news is this provides a clearer path to fruitful analysis by way of focusing on how various constraints will limit the scope of policy options.

Another implication is that significant policy constraints also significantly increase the potential for major changes in narrative.

For example, in 2021, investors assumed interest rates would remain low. That assumption was based on past policy tendencies. However, those past policy tendencies were formed in a period of extremely low inflation. In the context of the higher inflation of 2021, there was no longer the luxury of keeping interest rates exceptionally low. Even in 2024, with rates much higher than in 2021, the Biden administration was constrained by the political reality of having to appear to be fighting inflation. What happened was a disaster for bond investors — all because the narrative about what could happen with long-term rates changed when inflation arrived.

While there are plenty of investors just waiting for a return to the “good old days” of Quantitative Easing (QE) and low interest rates, policy constraints suggest this is unlikely. First, inflation remains a much greater threat. Second, central banks around the world have begrudgingly admitted that QE exacerbates inequality which means it will be reserved for emergencies. These are relatively new, and meaningful, constraints on policy.

This changes the game for handicapping long-term interest rates. Most importantly, the supply of government bonds will increasingly need to be purchased by private investors. They will demand attractive rates to compensate for the risk and that will mean higher rates than when price-insensitive buyers were the dominant force.

That’s not the end of things that can go wrong for bonds though. In addition, while the term premium has been rising, it is still well below historical norms. Also, while longer-term inflation expectations remain in check now, there is a good chance they will rise as countries get forced into implementing financial repression. Just because long-term rates are higher than they were doesn’t mean they can’t go higher yet.

In sum, there is a clear path, arguably a probable path, to some major changes in narratives that are likely to be very detrimental to both stocks and bonds. Sure, there will be ups and downs along the way. But these are the types of major changes that can make or break returns for investors.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.