Observations by David Robertson, 2/10/23

This blurb from John Authers at Bloomberg sets the stage appropriately:

It’s not unusual for people to differ over the economy. Such a difference of opinion over what we’re even worried about, however, is unusual. As Sandi Bragar, chief client officer at Aspiriant in San Francisco, says, it’s “almost like we're in a pinball machine; investors are just getting hit on different angles, running into different pieces of news and it’s hard to pull it all together.” If you’re confused, don’t be ashamed and be aware that you’re not alone. Uncertainty like this argues for diversification and caution.

True that. If you want to follow up on anything along the way, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

A chart by themarketear.com ($) above shows European stocks started rebounding last fall, but mainly on the strength of the euro. More recently, the euro has started dropping but stocks haven’t gotten the message yet.

Another chart below by themarketear.com represents another interesting disconnect. Longer-term, Nasdaq is clearly a rates play, but the last several weeks it has noticeably deviated from that relationship.

Finally, as Almost Daily Grants highlights below, IPO activity has also blossomed recently:

A key corner of the financial markets stirs to life after an extended hibernation, as seven firms will launch initial public offerings on U.S. exchanges this week by Bloomberg’s count. That would mark the busiest such stretch since the beginning of August and the second most active week since early February 2022, a noteworthy development considering that conventional IPO volume registered at a feeble $7 billion last year according to University of Florida finance professor Jay R. Ritter, a tally far below any calendar year going back to 1990.

The common thread amongst all these observations is they can be viewed alternately as “green shoots” of an emerging recovery or as bear market rallies that have become over-extended. While I was already leaning heavily toward the latter, the recent creation by Grant’s Interest Rate Observer ($) (Feb 10, 2023) of a “High Beta Index” (which has significant overlap with my “Exuberance” list) has me sold. It is up 91.5% since December 30, 2022.

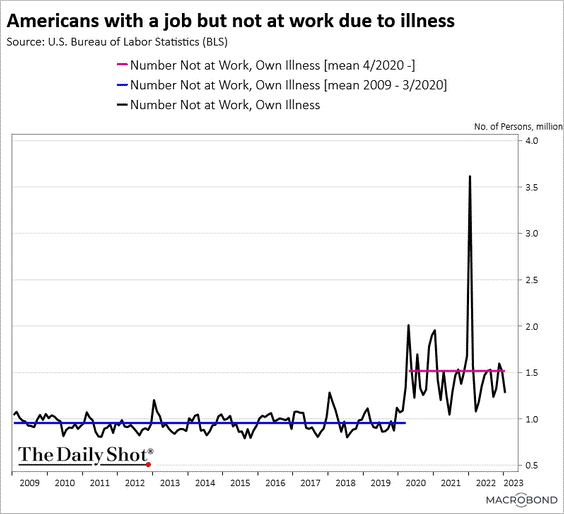

Labor

There are a number of possible reasons for this, not least of which is companies trying to protect healthy employees by insisting unwell ones stay at home. As such, it is definitely possible the trend returns to the pre-Covid normal. For the time being, however, this looks like one more pattern that has fundamentally changed since the pandemic.

Credit

US consumer spending has remained healthy, but that is no reason to be complacent. Partly it takes time for consumers to adjust spending patterns when things change - like interest rates going up or losing a job. Normally, the first hints that current spending levels aren’t sustainable show up in weakening credit.

This is happening. Chris Whalen reports, “the big take away from Q4 2022 earnings is that credit expenses are headed higher and at a brisk pace”. He also notes, “DQ [i.e., delinquency] rates on sub-600 FICO government loans are rising roughly 1% per month and are now in the mid-teens. This is a stunning statistic that nobody in the first narrative seems to have noticed”.

Stresses are beginning to show in auto finance as well. @AutomotiveLife1 reports, “67% of Americans Can’t afford the Cars they drive”. @unusual_whales reports, “Americans fall behind on car payments at higher rate than in 2009”.

Credit is also starting to get some attention in the business space as well. Even though credit spreads have come down since last fall and do not signal a broad-based threat yet, there are still signs of trouble.

Dan Ivascyn at PIMCO provides an interesting perspective on the situation. If rates stay at a fundamentally higher level due to inflation, he is probably right “this cycle is going to be different”. It could well be that higher rates today aren’t the problem so much as the need to eventually roll over debt at a much higher cost. In such a case, “a scenario of multi-year disappointments” is a very reasonable one.

Oil

Fall in petrol use in gas-guzzling US heralds shift for global markets ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/aa1a291e-4293-4b8d-8e33-2b6da4664d35

The 8.78mn barrels a day of petrol consumed in the US last year was 6 per cent lower than record volumes sold before the coronavirus pandemic. Consumption will continue to decline in 2023 and 2024, the US Energy Information Administration forecast on Tuesday.

The pattern toward lower gasoline consumption in the US is pretty clear to see - and is an important component of global demand for oil. Lower consumption has been driven by higher gasoline prices, the continued penetration of electric vehicles, and “less driving in cities, where working from home remains popular”.

Each of these reasons says something about the elasticity of oil demand. If prices go too high for too long, people adjust by driving less. If commuting becomes too much of a hassle, people work from home more. If the long-term proposition of gas-powered cars declines, people seek alternatives.

The bottom line is people do respond to oil prices by adjusting consumption. Perhaps one of the greatest consequences of the pandemic was triggering a permanent change in the speed and fluidity of consumer adaptation.

Currencies

This is a continuation of an ongoing discussion regarding currencies and balance of payments. I have a lot of sympathy for the argument that China is working aggressively to expand use of the yuan in order to reduce its vulnerability to the US dollar. I also have sympathy for the many factors that argue against a strong dollar position. The logic that large and growing debt and deficits is no way stay on top is intuitive and compelling.

Zoltan Pozsar, for example, has led one line of thinking that commodities will increasingly be used to disintermediate the dollar. Recently, Nouriel Roubini argued in the FT that “the relative decline of the US dollar as the main reserve currency is likely to occur over the next decade”.

While both make good points and highlight important changes to watch, they both also miss the elephant in the room. If not the US, then who else is going to suddenly start running huge deficits to pick up China’s surpluses? Or, as Michael Pettis has explained tirelessly, how is China going to redistribute its income, despite significant institutional obstacles, such that consumer spending increases and surpluses decline?

The problem is, as easy at it is to find faults with the dollar, it is even harder yet to answer these questions in a convincing way. It’s all relative. At the end of the day, then, I have come around to seeing the situation more as @georgemagnus1 does. It’s really pretty simple: You just can’t “run persistent bop [balance of payments] surpluses and restrict outward capital movements” and have a widely used global currency.

Inflation

The main point here is that when inflation becomes embedded, a lot of behaviors change. A specific example regards that of inventory management. Namely, in an inflationary environment, it is good to have lots of inventory because you can always sell it later at an even higher price.

This sounds mind boggling to business managers today because most have only experienced the opposite phenomenon. For them, it makes the most sense to minimize inventory in a disinflationary environment partly to lower the risk of inventory writedowns and partly to minimize capital invested.

In general, inflation creates an incentive to pull goods purchases forward and to accumulate stuff. In doing so, demand increases at the margin and, assuming supply doesn’t respond as quickly, prices go up. Then you have a self-fulfilling feedback loop.

Expand the framework a bit more and it’s easy to see that pulling demand for goods forward comes at the expense of other uses of cash, including the purchase of financial assets. As a result, as inflation sets in, not only does marginal demand for goods go up, but at the same time marginal demand for financial assets goes down. Don’t be surprised as this dynamic unfolds.

Monetary policy

Fed chair Jerome Powell spoke on Tuesday, presumably to clarify the Fed’s position after its press conference last week and after a strong jobs report on Friday. He said basically the same thing he said last week. That didn’t prevent some crazy gyrations as @biancoresearch describes:

The single biggest point I take from this is the rapidly diminishing effectiveness of the Fed’s “communication” strategy. The whole point of the strategy is to be clear and straightforward with intentions regarding monetary policy so as to minimize risks to financial stability.

Not only does the “communication” no longer seem to be working, it increasingly appears to be part of the problem. When financial market participants begin to selectively believe some elements of the communication, and selectively reject others, the communication itself no longer serves much purpose.

In many ways, this is a trap of the Fed’s own making. By opting to “jawbone” versus taking difficult actions, it opened itself up to being challenged. This is exactly what is happening. Markets don’t believe the Fed has the courage to keep monetary policy tight once the economy slows. We’ll see, but there is a very good chance somebody will be wrong: Either the Fed will hold its ground as growth slows or inflation will prove stickier than many people expect. Or both.

Investment wisdom

The Forgotten Lessons of 2008: Seth Klarman

https://investmenttalk.substack.com/p/the-forgotten-lessons-of-2008-seth

Any student of investing should go through as much of Seth Klarman’s work as possible. His thinking is clear, his writing accessible, and his lessons are timeless. I have always appreciated Klarman’s thinking but the longer I have been in the business, the more I realize how deeply insightful these lessons are.

One of my favorites is, “Nowhere does it say that investors should strive to make every last dollar of potential profit”. I like it because it’s true and almost nobody says it. Rather, investors get bombarded with statements like, “there could be 10% more upside”, and “If X crosses a certain level, it could break out”. This is the language of speculation and overreach, not of sensible, risk-aware, long-term investing. That last dollar of profit usually comes with traps and contingencies and yet … it can be just too alluring for some.

Another good lesson is, “Risk is not inherent in an investment; it is always relative to the price paid”. So many times people try to characterize certain types of investments as “risky” and certain ones as “safe”. This is a tempting simplification but as Klarman explains, there is no such risk or safety inherent to an investment; the risk is a function of price. Just look at 10-year Treasuries in the summer of 2020 - or even 2021. At those ridiculously low yields they were anything but safe.

Finally, I’ll throw in, “Do not trust financial market risk models”, as a top-three favorite. Having done a lot of quantitative modeling earlier in my career, I know as well as most what models are capable of … and what they are not. Models are simplified representations of reality. As such, they deal reasonably well with “normal” times. When things start getting funky, however, models can misrepresent in a lot of different ways. Often this happens because some critical assumption is violated in an extreme condition, and this is usually when you need help the most.

Investment landscape I

As mentioned above, a great deal of recent market phenomena can be viewed in two completely different ways: As evidence of early recovery or as part of a bear market rally. Chinese liquidity is yet another factor that can be added to the list.

This post also comes with a warning, however: “Economic road bump coming”. For now, China’s liquidity spurt appears episodic, not systemic. Insofar as this turns out to be the case, it fits well with the view that the recent move is more a short-term swoon than a longer-term return to normalcy.

Investment landscape II

America’s government is spending lavishly to revive manufacturing ($)

All this marks a huge reversal. For the past 40 years, successive American governments have followed a different prescription for growth: free-trade deals, low taxes and relatively little regulation, especially about where things are made. Indeed, America used to bemoan such policies when other countries adopted them.

“In recent decades the focus became very narrow,” Ms Yellen explains to The Economist. For the past year she has been touting an alternative vision, which she calls “modern supply-side economics”. It emphasises the beneficial effects of public investment—in training, social services, clean energy and the manufacture of certain goods. This agenda cleverly weds the aim of succouring manufacturing to several other goals, including reducing America’s emissions of greenhouse gases, limiting its dependence on imports of strategic goods and shoring up its technological lead over China.

Nice read in the Economist (h/t@Brad_Setser) regarding America’s newfound proclivity for industrial policy. Indeed, this is a big point since it marks “a huge reversal”. People who invest on the assumption of minimal government interference will be sorely disappointed - and wrong. This evolution in policy presents a different playbook, and different consequences. As the Economist notes, “In all sorts of ways, government help will bring government meddling”.

One of the ways in which this fairly bold policy initiative was promoted was by linking manufacturing jobs with climate change. Like it or not, it was smart politics. It’s industrial policy packaged as green initiatives.

Another way in which it was promoted was as part of an even bigger, geopolitical, vision. As Yellen commented, “so that’s not just about long-term growth in productivity, it’s also about national security.”

Finally, the Economist concludes, “Mr Biden’s complex political compromise is distressingly inefficient and definitely not the dawn of a new era of manufacturing-driven prosperity, but it will change America and the world nonetheless”. This sounds like an unusually objective assessment. For investors, it’s not about which political team wins or loses, but rather about appreciating the change that is happening.

Implications

The big question facing investors is whether to treat recent strong performance of financial assets as a signal of things returning to normal or as a short-term aberration in the context of longer-term headwinds. Inveterate bulls see the former, bears the latter.

With the US dollar rebounding and a number of assets clearly disconnecting from historical relationships, the evidence favors the interpretation of short-term aberration. Further, given the “long and variable” lags of monetary policy, there is a good chance we will start seeing the effects this year.

So, one implication is it appears speculative, if not outright foolhardy, to take big risks in front of these headwinds. It’s not hard to imagine the collateral damage coming: Higher bankruptcies, even more problems with illiquid investments, and the ongoing wind down of asset-backed securitization, among others. Until these problems really flare up, however, the waiting will be the hardest part.

Another implication is it looks like government efforts to meddle in the economy are here to stay. While that may seem appalling to some, it’s not helpful to fight it. In fact, Russell Clark is going so far as to calling “investing in line with government policy” a “mega trade”, and claims he is going to do it now with all his investment ideas. If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.