Observations by David Robertson, 2/11/22

Stocks were cruising along most of the week until Thursday when CPI was reported and came in hot at 7.5%. Per the report, “The all items index rose 7.5 percent for the 12 months ending January, the largest 12-month increase since the period ending February 1982.” On that troubling comparison, futures immediately dropped. If you have questions or comments, let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

One of the prominent trends for the year-to-date as well as the past week has been the rise in Treasury yields. The dramatic change in landscape is extremely visible in the 2-year rates:

The 10-year yield (pictured below) also got bumped up. It had a big spurt the first week of the year and another big spurt this past week. That said, with short-term rates rising so much faster, the yield curve is also moving rapidly toward inversion.

This breakout in yields has also taken on a very international flavor. Eurozone rates popped last week on high inflation and emerging market central banks have been pushing back on price pressures for a while now.

Rate news got even more interesting later in the week as the odds of a 50 bp hike in March jumped on Thursday and the idea of an emergency rate hike in February became a real possibility. Indeed, the Fed has scheduled an “expedited” meeting for Monday the 14th to huddle up and figure out what to do. It certainly looks like we are edging closer to some real turmoil.

Credit

"Looking For Truth? ... In Bonds There Are Fewer Lies"

https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/looking-truth-bonds-there-are-fewer-lies

Since 2008, (the opening salvo of the Global Financial Crisis 2007-2031), there has been a feeding frenzy in corporate bonds as low rates and insatiable demand allowed any junk companies unfettered market access. What did they do with the trillions of dollars of debt they raised? Did they spend it on new plant and equipment, or creating new jobs and markets? nope. Most of it has been spent buying back equity (share-buy-backs) which pushed up the stock price and, and coincidently, management bonuses!

One point that comes out of this piece by Bill Blain is that since the GFC, there has been a “feeding frenzy” in credit of all types. This experience sticks out as a historical aberration and therefore should be expected to resolve at some point.

Another point is that a broad span of excessively cheap credit has done two things that are detrimental to future economic growth. For one, it has pulled forward spending so future demand will be lower than it otherwise would be. For another, cheap capital has been invested in financial engineering rather than capital spending, which renders future productivity lower than it otherwise would be.

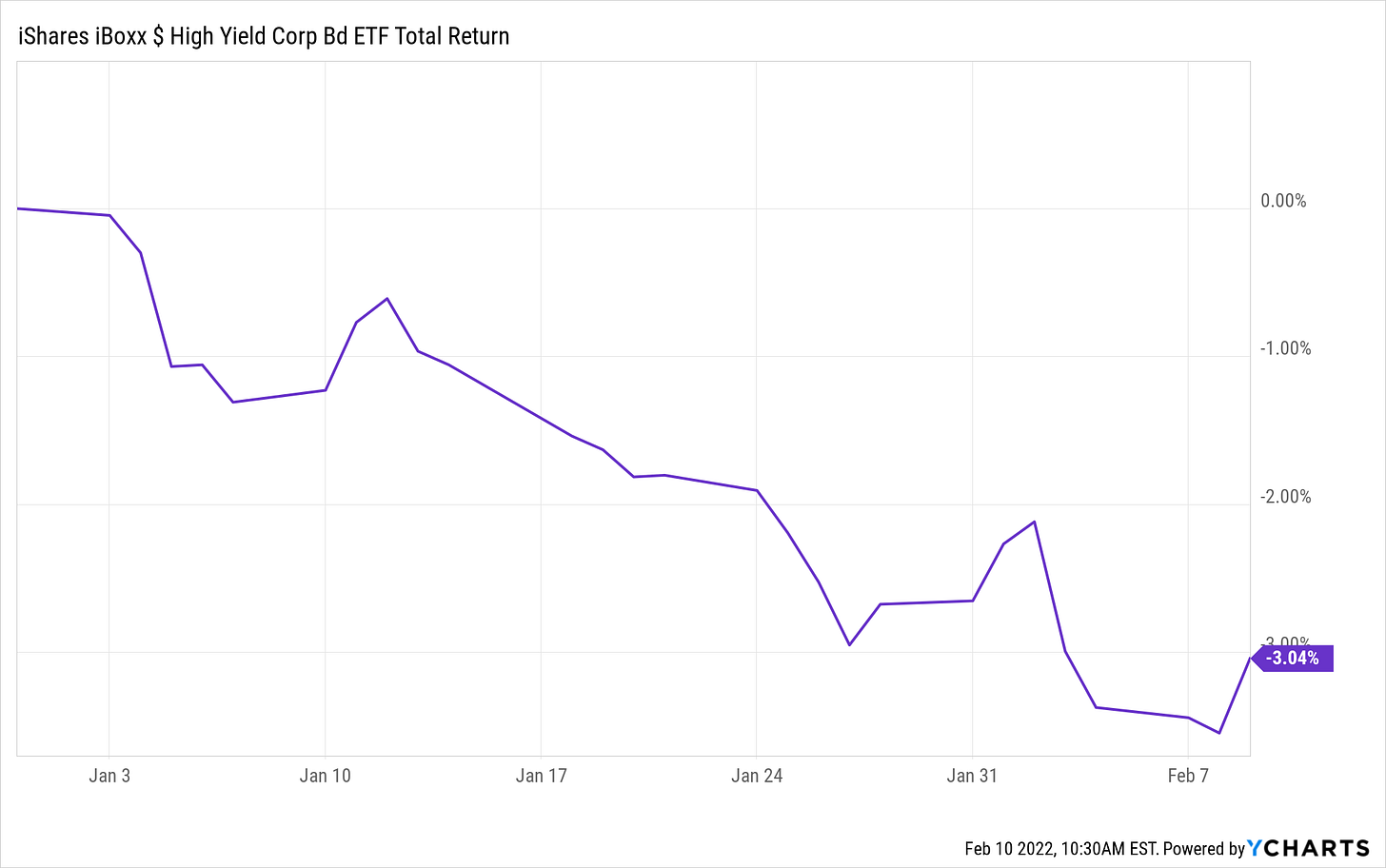

Finally, credit is a lead indicator for economic conditions. As companies need to replace lower cost debt with higher cost debt, profits go down, all else equal. It takes time, but it is a game of attrition as weaker companies eventually succumb to more challenging financial conditions. The ETF, HYG, serves as a good general indicator of credit conditions.

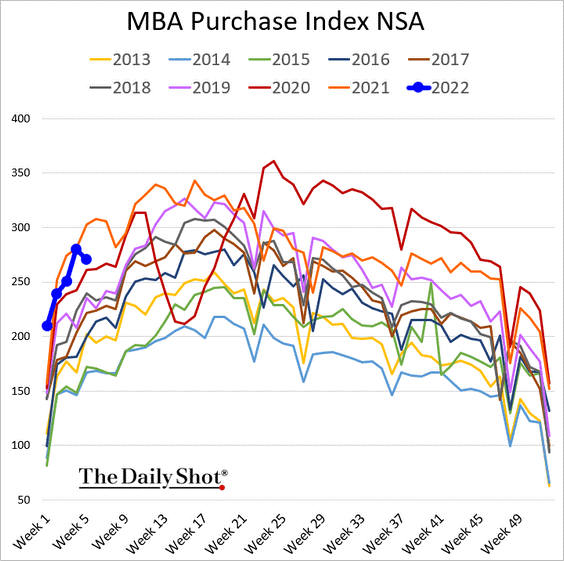

Of course, more challenging credit conditions are not confined to businesses alone but will affect households as well. As conventional mortgage rates push up toward 4%, the environment for buying a home has become considerably less attractive. It looks like this is just starting to manifest itself in sequentially lower mortgage applications.

Public policy

The immediate consequences of the ruling [that revoked two federally approved permits to complete the Mountain Valley Pipeline project] are as follows. First, incremental natural gas produced in Appalachia will be stranded there, driving down prices in that region while increasing prices for the rest of the US market, which was counting on ready access to Appalachian production to meet their future needs. Second, the decision will limit the ability of US LNG export terminals to meet global natural gas demand, further eroding our geopolitical power and emboldening our adversaries – forcing us to make unseemly alliances with despots like the Emir of Qatar. Finally, the decision will make it even harder to attract much-needed capital for future domestic energy development projects.

When will the music stop?

https://www.ft.com/content/f9eb639d-0d4c-4a9f-b4f0-2e2abad0f558

My preference would be for radical micro-economic reforms. The US tax system incentivises debt financing, rewards shares buybacks, punishes patient capital, and underinvests in its people and workforce.

The great strength of US capitalism is its ability to reinvent itself and innovate. US capitalism’s great sin is to punish the numerous left-behinds for their plight. It is not only possible but urgently desirable to confront the system’s gross human inequities and inefficiencies without sacrificing the innovation. I would like to see politicians talk more in these terms.

The point here is not so much to takes sides on the particular issue of a pipeline project or even energy policy in general. Rather, it is to highlight the even bigger problem that so often manifests itself in public policy: Too often, difficult tradeoffs are avoided altogether in favor of obfuscation, avoidance, and simpler stories. The end result is misallocation of resources and misdirection of priorities.

This isn’t a huge problem in an environment of prodigious resources and flexible morality, but quickly becomes one when resources become scarce and negative consequences become more apparent.

Even then, it isn’t necessarily a huge problem - if you have a plan. This is the problem, however. In too many cases, there simply is not a cohesive policy framework that outlines how to make tradeoffs consistently and effectively. Without such a framework, policy decisions tend to lurch awkwardly and unpredictably and often counterproductively. This is where we are now.

I’m not claiming there are easy answers. But, we should at least try to do the best we can with what we have. As Ed Luce suggests, many times significant improvement can be achieved simply by eliminating counterproductive incentive systems. That is a sensible place to start.

Finally, whether the issue is energy transition, which I have mentioned many times, industrial policy, labor force issues, social safety net, foreign policy, or other areas, the cost of inconsistent and arbitrary public policy initiatives is rapidly increasing. Public policy is supposed to make things better, not worse.

Monetary policy

The news of additional reporting failures at the Fed, this time by Fed Chair Jay Powell, came out this week but haven’t gotten a lot of attention, at least not yet. One point is these are massive violations. It now appears the ethics breaches at the Fed have not just been an issue of one or two bad apples, but a systemic lack of oversight. It is hard to view this as anything other than a shameful contravention of the public’s trust.

It also comes at an inconvenient time. Powell’s confirmation vote is imminent and the country is looking for a stable Fed to steer monetary policy through a very challenging landscape. The last thing markets need is a major inflationary scare at the same time Fed leaders are distracted by extracurricular activities.

Investment landscape

BofA Says Endgame Begins: Global Rate Shock Has Triggered Tech Wreck, Recession Countdown And "Systemic Event" ($)

And since most people tend to forget this simple heuristic, Hartnett offers another reminder what the endgame is: "historic solutions to excess debt: war, currency debasement, repudiation, inflation."

Rates shock poetry, Feb 04 2022 at 12:25 ($)

https://themarketear.com/premium

On the latest rates shock he [Michael Hartnett] writes: "Euro-area unemployment rate record low 7.0%, inflation record high 5.1%, yet ECB policy rate is -0.5%...you do the math; G7 QE programs ending quickly, rate hike expectations jumping, Fed/ECB rate hikes encourage speculators to test BoJ YCC policy resolve; big capital flows to US stocks driven by negative rates in Europe & Japan ending."

One great point is keeping the endgame in mind. The only practicable solution to excessive debt is currency debasement and that happens through inflation. Quite arguably, despite its better efforts, the Fed failed miserably in this effort after the financial crisis because it couldn’t raise inflation enough to moderate the debt burden. Now that it has, it’s plan is finally coming together, albeit less smoothly than intended.

Another good point Hartnett makes is that an important turning point was reached last week when the interest rate shock went global. With inflation still also running high in the Eurozone, there will also be enormous pressure on the ECB to begin tightening its monetary policy as well. While it was possible to entertain the notion the Fed would mainly just talk tough about tightening policy, now it is clear the pressures are widespread and much harder to sidestep.

Gold

Gold and real rates, Feb 9 2022 at 04:25 ($)

https://themarketear.com/premium

Gold has managed holding up very well despite real rates having moved "against" the gold narrative. Do you get the feeling of when something should move lower, but it refuses? We all know what usually happens instead...

One of the theories about gold is that it moves inversely with real rates. When real rates move up, gold normally moves down, and vice-versa. The logic is straightforward: The higher real rates go, the more investors earn from financial assets and the higher the opportunity costs they incur from holding gold instead.

That framework is a good rule of thumb but, as if often the case, reality is more complex. For one, TIPS yields (which are normally used to represent real rates) are only protected to the degree that CPI captures inflation. And, there is a large body of evidence indicating CPI pretty systematically understates inflation.

For another, the Fed has been actively purchasing TIPS and owns over 25% of the outstanding issues. It is hard to imagine such aggressive purchasing has not distorted prices, and therefore yields, to at least some degree.

Another problem with the real rate theory is that it focuses on the direction of rates more than the level of rates. This makes sense because most historical periods have positive real rates. That’s not true today, however.

A sustained environment of negative real rates changes the logic. In this case, the opportunity costs flip. Financial assets impose losses, in real terms, on their owners. At the same time, gold retains its value and does not depreciate.

The result is gold should be systemically attractive in an environment of sustained negative real rates. Indeed, as I mentioned in the previous section, the endgame in managing excessive debt appears to entail exactly that - a period of sustained negative real rates.

Of course, there are always the usual caveats about the unpredictability of short-term trading action, but the longer-term proposition for gold is not significantly diminished by this intervening period of rising real rates. One last point is that it is in the best interest investors in physical gold to act before demand becomes too obvious. Once it does, premiums often go up faster than the price of gold itself which makes acquisition more costly.

Investment strategy

I often don’t agree with the prickly demeanor of Cliff Asness but I rarely disagree with his research - it’s just too good. With this tweet he directly addresses a major problem with investing in general and in doing so, touches on yet another one.

The major problem is drawing erroneous conclusions. This happens a lot because there are all kinds of incentives to pull in money to “new” strategies that outperform. Often this is simply a matter of sales-driven cultures doing what they do - telling stories. Often, however, erroneous conclusions are also drawn not due to any ill intent but due to bad research.

One of the leading causes of bad research is insufficient perspective. Many studies, for example, don’t consider a long enough period or focus too narrowly on a period that is not representative of the broader expanse of history.

This is partly the problem with the Wealthfront research. After a period of thirteen consecutive years of exceptionally easy monetary policy, and a period during which the value style significantly underperformed, they decided to get rid of the “value” style. As Asness shows in his work, another factor at work during this particular period of time is that the change in valuation of “growth” stocks significantly exceeded that of “value” stocks. In other words, if you normalize for the changes in valuations over that period, a significant portion of the performance differential goes away. All else is not equal.

This leads to another point the tweet highlights indirectly: Passive approaches automatically subject their investors to all kinds of erroneous conclusions. It can, for example, take the form of Wealthfront abandoning the value style at arguably the worst possible time. It can also take the form of overly exposing investors to large, overvalued stocks in major indexes. Either way, investing is a dynamic exercise and by virtue of selecting passive approaches, investors choose to not adapt to the changing conditions. I predict a long run of disappointment with passive investing.

Implications for investment strategy

The topic of tail risk arose in the financial crisis in 2008 and is beginning to make the rounds again. Indeed, with record high stock valuations, interest rates that are beginning to rise off of record low levels, a change in monetary policy stance, high inflation, and several geopolitical hotspots, there are plenty of things to worry about if one is so inclined.

The relevant investment questions are, “How much should one worry about tail risk?”, and “What should one do about it?” During the years since the financial crisis tail risk was effectively underwritten by the Fed and other major central banks under the pretext of maintaining smoothly functioning markets. In addition, Powell clearly highlighted the Fed’s continued desire that markets remain “orderly” during the Fed’s last press conference. As a result, we can assume a fair amount of intent is there.

One challenge will be leverage. The extended period of weak growth but downside protection from the Fed supported a popular playbook: Find modestly profitable opportunities and leverage them to the hilt. This will be extremely hard to undo in an orderly way and presents many opportunities for forced selling.

Another challenge is the data pattern. Thirteen years of ultra-easy monetary policy underpins countless algorithms that drive investment decisions. It will take time and countervailing evidence to undo this. Tough talk from the Fed will only go so far; markets will need to experience the brutal reality of higher rates before adapting to them.

Yet another challenge will be deciding who is allowed to fail. As rates go up, marginal businesses will not be able to afford to roll debt over. Small businesses don’t have systemic effects, but larger ones could involve thousands of job losses among other effects. The failure of leveraged hedge funds could also have widespread effects just like LTCM did in the late 1990s. Finally, if primary dealers get into trouble, they would pose an enormous threat to the financial system.

How orderly can any exit from easy monetary policy be when there is so much leverage in the system and so many players are heavily exposed to financial assets? Who would the Fed save and who would it allow to fail? This is the problem Lehman Brothers presented in September 2008. The situation has all the chaotic underpinnings of avalanche conditions. The best one can hope for is small, localized blow-ups that never manifest in contagion.

For the time being, there seems to be something of a “deer in headlights” phenomenon. Large investors who know the risks but are heavily exposed can’t do very much but freeze in place. With such low liquidity, any moves would send prices reeling. As a result, it’s probably time to cue the creepy music at the end of a horror movie and watch how the ugliness unfolds.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.