Observations by David Robertson, 2/17/23

Stocks have been surprisingly resilient despite weakening fundamentals and serious storm clouds forming. If you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

There are a lot of products that serve as an insurance policies of sorts by providing high returns when an “accident” happens. The value of that insurance policy varies, however, depending on the price you pay for it. This note simply highlights that current prices for insuring against accidents is pretty high. Sometimes the cheapest protection is outright avoidance.

Just a reminder that there are still a lot of absolutely terrible investment products out there. Further, judging by my email inbox, salespeople are getting getting pressed hard to drum up business. The depressing interpretation is the best the industry can do with all kinds of great technology is to produce an even wider range of crap.

The kinder, gentler interpretation is that despite a lot of bad stuff, there are new products that are innovative and useful. It takes some work to find the needles in the haystack, but they are out there.

Labor

Corporate America is struggling to adapt to Gen Z ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/66e84b93-ada1-4cbb-92a7-cab13b9a2b7f

But peer a little closer, and there is a twist: Visa’s move is partly sparked by a scramble to make sense of the behaviour of “Gen Z”, or the cohort born between 1997 and 2012. “[Gen Z] wants control,” explains Charlotte Hogg, chief executive of Visa Europe …

But the most striking issue that defines Gen Z is something else: personalisation. A cohort steeped in digitisation and smartphones considers it entirely normal and desirable to customise everything — from their music, media, food and holidays to their politics, gender identities and working practices.

Just as we are trying to make sense of labor force numbers that have been distorted by shorter-term Covid-related phenomena, we also have longer-term demographic changes further complicating the situation. As @Econimica points out, we are running out of workers. The age groups that dominate the working population are no longer growing. Further, those age groups are right at peak employment.

In addition, as Gillian Tett highlights in the FT, Gen Z is broadly characterized by its predilection for personalization. Gen Zers prefer to customize everything … including their “working practices”.

Put these two observations together and its easy to see where there is likely to be conflict. Workers want things their own way - their own work environment, their own hours, and their own culture. With labor conditions still very tight, businesses will have to come up with some combination of higher pay and more flexibility in order to keep their ranks filled. As such, this looks a lot like a persistent inflationary pressure.

China

China’s ultra-fast economic recovery ($)

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/02/05/chinas-ultra-fast-economic-recovery

Can this frenetic pace [of consumer spending] be sustained? Optimists point out Chinese households are unusually liquid. Their bank deposits now exceed 120trn yuan ($18trn), over 100% of last year’s gdp, and 13trn yuan more than might have been expected given pre-pandemic trends, according to Citigroup, a bank. These deposits could provide ammunition for a bout of “revenge spending”.

Yet the ammunition may be set aside for other purposes. Much is composed of money that nervous households kept in the bank rather than using to buy property or ploughing into a mutual fund. They are unlikely now to lavish it on goods and services. More likely, reckons Citigroup, is a bout of “revenge risk-taking”, as households gain confidence to buy assets that are less safe but potentially more rewarding than a bank deposit.

Amidst all the chatter about Chinese consumer spending taking off, this article provides some nice background and alternative perspectives. What is not in question is the fact that Chinese households are “unusually liquid”. The global macro parlor game is guessing what will be done with all those savings. The top candidate seems to be a period of “revenge spending”.

This echoes the behavior in the US where consumers busted out to go on vacation, get away, and do anything other than stay in the house and do nothing. While there will no doubt be some of that, most projections of US consumer behavior onto Chinese consumers tend to be imperfect at best.

One alternative that makes sense is “revenge risk-taking”; i.e., investment. In an environment of capital controls, low savings rates, and unequal distribution of income, one of the more obvious ways to get ahead is to invest. As a result, this notion is likely to have some legs to it.

That said, things have changed. A lot of purchasers of property have suffered price declines or have paid significant sums for properties that may never get built. Further, tech investors certainly learned a lesson about how much damage can be caused when public policy reverses quickly and unexpectedly. Finally, risk assets have benefited from ever-increasing liquidity. It does not appear as if this is a good assumption going forward.

A third possible option is consumers simply retain a greater baseline level of savings. It is clear from the US and other parts of the world that Covid changed some things permanently. Many people re-evaluated life priorities and made changes. Other reconfigured work/life tradeoffs. Still others were left with a much different perception of risk in the world. It is hard to imagine none of these sentiments will be experienced in China.

Monetary policy

Hiking at $60b a Month

https://fedguy.com/hiking-at-60b-a-month/

The Fed cannot force banks to offer depositors higher rates, but QT side steps them and does job by brute force. Every month $60b in deposits yielding around 0% are replaced with $60b in Treasuries yielding around 4%, and deposit rates are also slowly rising. The sizable yield upgrade being forced onto the market may indicate a more impactful QT. When rates were low, Treasuries and deposits were plausible substitutes. But rates are not low any more.

One of the important points this article addresses is the notion that a really important goal of central banks is to re-establish the efficacy of monetary policy. The flood of Quantitative Easing achieved the goal of encouraging greater risk-taking, but came at the cost of undermining the ability of central banks to rein things in later. This aspect of monetary policy is conveniently overlooked by most monetary policy commentators.

Joseph Wang is exactly right that when rates were low, “Treasuries and deposits were plausible substitutes”. In other words, at very low rate levels, Fed actions do virtually nothing to change behavior. Now, with higher rates, banks will need to start competing to retain deposits. This will have the effect of giving the Fed greater control over monetary policy.

Another thing higher rates will do is to increase funding costs for banks. This will decrease their net interest margin (NIM) and make them less profitable. This is happening at the same time that higher rates undermine the value of their bond holdings and therefore the value of their capital.

I don’t worry too much about banks causing systemic financial problems because I think the Fed will be broadly supportive (in the interest of maintaining financial stability). That doesn’t mean they won’t be facing some serious headwinds for a while though.

Risk management

Great thread here by @biancoresearch. While many observers have noted the recent prominence of 0dte (0 days to expiry) options, few have highlighted exactly how they might cause problems.

Here is exhibit 1. A huge chunk of traders and portfolio managers manage risk by way of models built on VIX. Insofar as VIX is increasingly unrepresentative of market risk, as appears to be the case given the large gap in implied volatility between VIX and 0dte options, risk models are not adequately capturing real market risk.

Not surprisingly, this has echoes with the GFC. Then, the widespread assumption was that house prices couldn’t go down, at least not by very much. Of course, once that assumption proved false, it revealed a great deal more risk than was presumed.

There are other echoes as well. The odte trend appears to be driven largely by regulatory arbitrage. In addition, risks are managed mainly through options rather than by changing underlying exposure (i.e., selling assets). Finally, there is a self-fulfilling feedback loop. Perceived risk is low - which incentivizes purchase of risk assets - which decreases volatility even more.

Is this THE smoking gun? Hard to tell - and it really doesn’t matter. What does matter is risk is increasing as some pockets of market behavior are driven by bad modeling. What also matters is positive feedback loops like this are not stable. They normally keep going until something breaks.

Investment landscape

Alas, the resulting ripples kept radiating out in ever-widening concentric circles as the effects of Inflation reached broader and broader markets: first Oil and Gas markets, then derivative markets like fertilizer, food, and petrochemicals, then consumer goods and services more generally, and finally wages and shelter.

Eventually these Inflationary Ripples meet some kind of resistance and bounce back as counter-ripples. The initial counter-ripples were relatively easy to predict because of the calm initial conditions. As these counter-ripples crash into the original ripples, some waves get canceled out due to “destructive interference” (see the embedded thread above about Destructive and Constructive Interference), resulting in Deflationary Counter-Ripples that counteract some of the Inflationary Ripples.

This is a great characterization of the macro environment by Michael Kao, aka @UrbanKaoboy. The vast majority of environmental descriptions I come across argue for one direction or the other; bull or bear. Kao refuses to be confined by this false choice and describes a third way.

This doesn’t mean the third way is especially attractive. As he puts it, “The Macroeconomic Pond is now in this state of infinite choppiness, as endless permutations of ripples and counter-ripples interact in a soup of chaos”. He calls it the “Big Chop”.

As he elaborates, “Now that we’re in a choppy pond of ripples and counter-ripples, it has become much more difficult to identify clear trends, and perhaps the better modus operandi as an investor is to at least question/challenge the idea that every ripple is actually the beginning of a large wave”. He concludes, “The biggest danger I see right now is over-trading the Big Chop and latching onto every ripple and counter-ripple as if it were the beginning of a momentous new regime …” Well said.

Investment landscape II

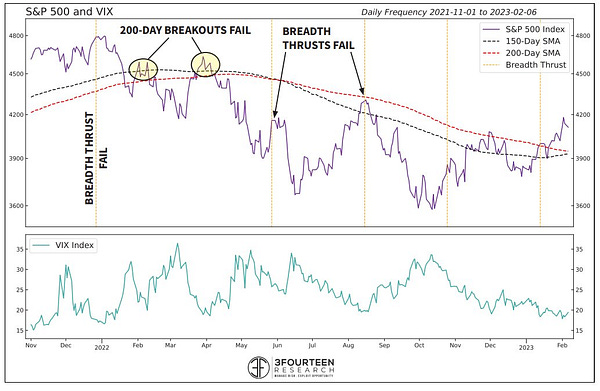

One of the phenomena I observed since the GFC was the growing use of technical analysis. Given that most traders I have studied downplay the significance of technical analysis in their own process, it begs the question of why so many others gravitate to it?

I have a couple of hypotheses. One is it is intuitive and easy to get started. It doesn’t involve a lot of numbers or fancy formulas, at least not overtly to users, and that makes it a lot more accessible than fundamental or quantitative analysis. Sure, it takes study and skill to practice it well, but when stocks keep going up as they did in the post-GFC/Quantitative Easing era, how much did it matter?

That leads to a second hypothesis. Technical analysis became extremely popular as lots of retail traders entered the market because it provided an ostensible explanation as to why stocks were going up. In my opinion, it wasn’t a good explanation, but that didn’t matter.

Well, it matters now. With inflation getting fired up and Quantitative Easing being reversed into Quantitative Tightening, all of a sudden technical signals are not working nearly as well. The main point is not to disparage technical analysis, but rather to highlight that it is but one way of looking at markets. If you invest for the long-term, you need to have a full tool kit.

Liquidity

I have been harping for some time about the importance of liquidity in driving market action. Money comes into the system and it has to go into something. That creates buying pressure somewhere. Money comes out and something has to be sold. @DowdEdward lays it out as well as anyone in the tweet above.

As a result, while there is always noise created by short-term trading, the more substantive and lasting changes in asset price levels usually come from structural shifts - such as from the rate of money creation, the availability of credit, and structural shifts in asset allocation.

Higher inflation has forced the Fed to significantly shift its position from prodigious money creation to gradual but persistent money destruction through its Quantitative Tightening (QT) program. On the margin, this causes investors to sell stocks in order to purchase new issues of Treasuries. This is the crowding out effect.

Of course, there are almost always complicating factors. For example, liquidity provisions by China and Japan more than offset tightening by the Fed last fall. Those efforts appear more tactical and short-term oriented, however.

Going forward, the Fed has been clear in its intention to continue QT for a few years. Given this, and the substantial increase in expected Treasury issuance, someone is going to have to sell something, the only question is what price will it take to lure the marginal buyer? That price is not likely to be good for financial assets.

Implications

In the context of still-high valuations and broadly negative liquidity conditions, the implication for long-term investors is fairly straightforward: Lean hard towards safety, i.e., short-term Treasuries or money market funds.

Such a straightforward conclusion may lead more risk-tolerant investors to try to exploit the other side of the trade, but that would be a mistake. As Michael Kao describes in his “Big Chop” thesis, it’s just really hard to tell much of anything in the short-term. This makes it very hard to gain the necessary conviction to make trades of any significant size.

For those who are actively engaged in the investment process, this may come across as frustrating. Understandable. For others, however, frustration has been having to choose between owning expensive stocks and risking a selloff, and sheltering in cash but absorbing the brunt of inflation. Now, at least, investors get paid to wait - and that’s a nice change.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.