Observations by David Robertson, 2/2/24

Lots of earnings, an FOMC meeting, and a Treasury Refunding Announcement all going on this week. Let’s jump right in.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

Google reported numbers on Tuesday that were mainly in line with expectations and the stock sold off after hours. Microsoft reported numbers that beat expectations handily and the stock stayed basically unchanged. Both reflected the pattern of “buy the rumor, sell the news”.

On Thursday, the earnings environment was different as both Amazon and Meta posted good results and very strong performance after hours. Apple’s report was gloomier, but not enough so to deflate sentiment. It seems traders have already pre-ordered their S&P 5000 hats.

The possibility that stocks are getting ahead of themselves is showing up in other ways too. Lee Adler ($) recently highlighted the eroding correlation between stocks and foreign central bank cash at the Fed. Does this prove stocks are overshooting? No. Does it jive with lots of other evidence that stocks are breaking away from useful historical relationships? Yes.

Finally, Treasuries took quite a ride during the week. With yields declining most of the week on expectations the Fed would be lowering rates soon, they took another dive on Thursday in response to credit problems at banks, apparently with the expectation looser monetary policy would be required to deal with the problems. On Friday morning, the payrolls report was stronger than expected and yields rapidly reversed higher again. Absolutely amazing volatility in the Treasury market.

Banks

The exercise of extracting information content from the important announcements from the Treasury and the Fed on Wednesday was made more difficult by the implosion of New York Community Bancorp (NYCB). The company reported on Wednesday morning and said it was cutting its dividend as a result of unexpected credit weakness. In case NYCB isn’t a household name for you, it purchased the deposits of Silicon Valley Bank last year.

At any rate, the stock was down on the order of 40% on Wednesday but also provided an important backdrop to the monetary announcements. First, the banking industry the Fed has gone to great pains to assure everyone is safe, clearly is not as safe as it let on. This probably explains the Fed’s sudden interest in tapering QT and the removal of the statement, "The U.S. banking system is sound and resilient," from its latest press release.

The effects were felt much further away than that though. The 10-year Treasury yield, which started the day down, plummeted further after the NYCB results, in expectation that bank problems will once again trigger monetary life support.

At very least, we now know banks are not as healthy as the Fed has been letting on. In addition, while it is fair to expect the Fed to step in if banking problems become serious enough, it is helpful to remember the Fed’s response to the mini-banking crisis early last year was far more targeted than prior responses. Indeed, the Fed has already confirmed the Bank Term Funding Program it developed in response will expire in a couple of months.

After the NYCB announcement, the shares of Aozora Bank in Japan dropped 20%. The principal cause was higher credit costs which were attributed to commercial real estate in the US. So, another indication from these announcements is the slow motion train wreck of commercial real estate is still in process - and becoming increasingly visible.

Credit

What does a yield buy?

https://mailchi.mp/verdadcap/what-does-a-yield-buy

While yield varies greatly across time, credit quality does not vary nearly as much.

What this brings to light is that targeting a yield makes very little sense because yield can mean very different things over time.

Figure 1: What Credit Quality Does a 7% Yield Buy?

I really like this piece by Verdad Capital because addresses what I believe is one of the biggest problems in the investment business. I also like it because it does so by taking a fresh look at the problem.

Most investment plans start with an “expected return”. For individuals, that’s usually the return needed from investments to fund spending in retirement. For pension funds, it is the return on assets needed to match the liabilities of promised pensions.

The next step is to figure how to generate that return. Most often that is done by looking at the historical returns and correlations of major asset classes. What Verdad exposes, however, is there is no set answer for what those returns will be. While actual credit quality is relatively stable over time, the pricing changes considerably. A goal of 7% yield could have been satisfied with AAA bonds in 1999, but would have required CCC bonds in 2020. That’s a totally different investment proposition.

The main point is it doesn’t make sense to start with your return goal. The market doesn’t care what you want. Rather, “It makes more sense to ask what your credit quality pays.” In other words, it makes more sense to work the other way around by asking what the market is offering and determining whether it is a good deal or not.

This is exactly the same concept as applying valuation to stocks. Rather than starting with a return that one would like to attain, it makes more sense to determine the relative attractiveness of the offer by the market. If it’s a crappy deal, you should look somewhere else.

US Consumer

The Effects of Credit Score Migration on Subprime Auto Loan and Credit Card Delinquencies

In this note, we show that the very large increases in subprime delinquency rates are in large part driven by pandemic-era shifts in the credit score distribution, or upward "credit score migration." Over the course of the pandemic, many consumers saw an in increase their credit scores sufficient to move out of the subprime category, and the share of borrowers with subprime scores decreased to the lowest level seen since the late 1990s. We provide counterfactual calculations that hold borrowers' credit scores at their 2019:Q4 levels to show how much the upward migration in scores has contributed to the sharp rise in the subprime delinquency rate. We find that counterfactual subprime delinquency rates were both considerably lower and have shown more muted increases. Thus, the historically high delinquency rates for auto loans to subprime borrowers overstates to an important extent the overall stress among borrowers more broadly.

There is a story being told about the economy that says higher rates and the expiration of pandemic era income support and forbearance programs are really starting to bite US consumers. It’s only a matter of time before the economy screeches to a halt.

While there is definitely truth to the story, it is not the whole story. Yes, subprime delinquency rates are going up, but mainly because the share of subprime borrowers is going down. The share of subprime borrowers is going down because the credit of many of those borrowers is improving and they are migrating out of the subprime category. This is a good thing!

This is not to say there aren’t still significant challenges for a number of subprime borrowers; that’s not true. However, the trend in the statistics is not nearly as onerous as some stories make them out to be either.

Inflation

The U.S. Economy is Roaring. Why Should Rates Come Down? ($)

https://theovershoot.co/p/the-us-economy-is-roaring-why-should

It is worth repeating that the normalization in aggregate inflation has thus far been driven by the prices of manufactured goods and commodities most sensitive to global supply conditions rather than the consumer services most sensitive to domestic demand conditions. In fact, the price index for consumer services excluding utilities, housing, and imputations of implicit prices for financial services, gambling, nonprofits, etc., which Fed officials have flagged as best reflecting underlying inflationary pressures, is still rising persistently faster than it was before the pandemic.

Most of this article by Matt Klein discusses monetary policy in the context of surprising strength in the economy, but it also raises an important point about inflation: The recent moderation in inflation has been “driven by the prices of manufactured goods and commodities most sensitive to global supply conditions rather than the consumer services most sensitive to domestic demand conditions.” In other words, the prices of goods from outside the country are moderating while the prices of services within the country are still rising at a decent pace.

The most obvious takeaway is the inflation picture is not simple or one-dimensional. There are several cross currents and any attempt to characterize inflation simplistically misses important nuance (and risks). The bifurcated nature of inflation also raises interesting questions I have touched on before.

For one, it puts China in the spotlight as a potential source of global deflation. While China’s struggle to restructure bad real estate debt has been an ongoing problem, the struggle hit a new plateau this week when Evergrande was ordered to liquidate. China is clearly trying to address the issues but hasn’t yet gotten ahead of the game.

Low confidence is exacerbating already low demand. Further, struggling manufacturers will sell at almost any price to generate cash and some will abroad to export excess product. In short, China looks to be more of a drag, rather than a source of growth, for many markets, not least of which is commodities.

Within the US, however, incomes are still mostly healthy and spending continues apace. At the same time, labor supply is constrained. As a result, unless and until those conditions change, wages are likely to keep going up. With services accounting for over 75% of the economy, this matters.

One point to takeaway is there are different puts and takes to account for in any outlook on inflation. These underlying tensions not only make the outlook inherently uncertain, but also make it vulnerable to dramatic change.

Second, and relatedly, there are a lot of risks and many are to the upside. Whether it be geopolitical risks to supply chains, heightened trade tensions, threats to commodity supplies, increasing wages, or increasing insurance costs, there are plenty of ways to be wrong in expecting inflation to settle at a very low level.

Monetary policy

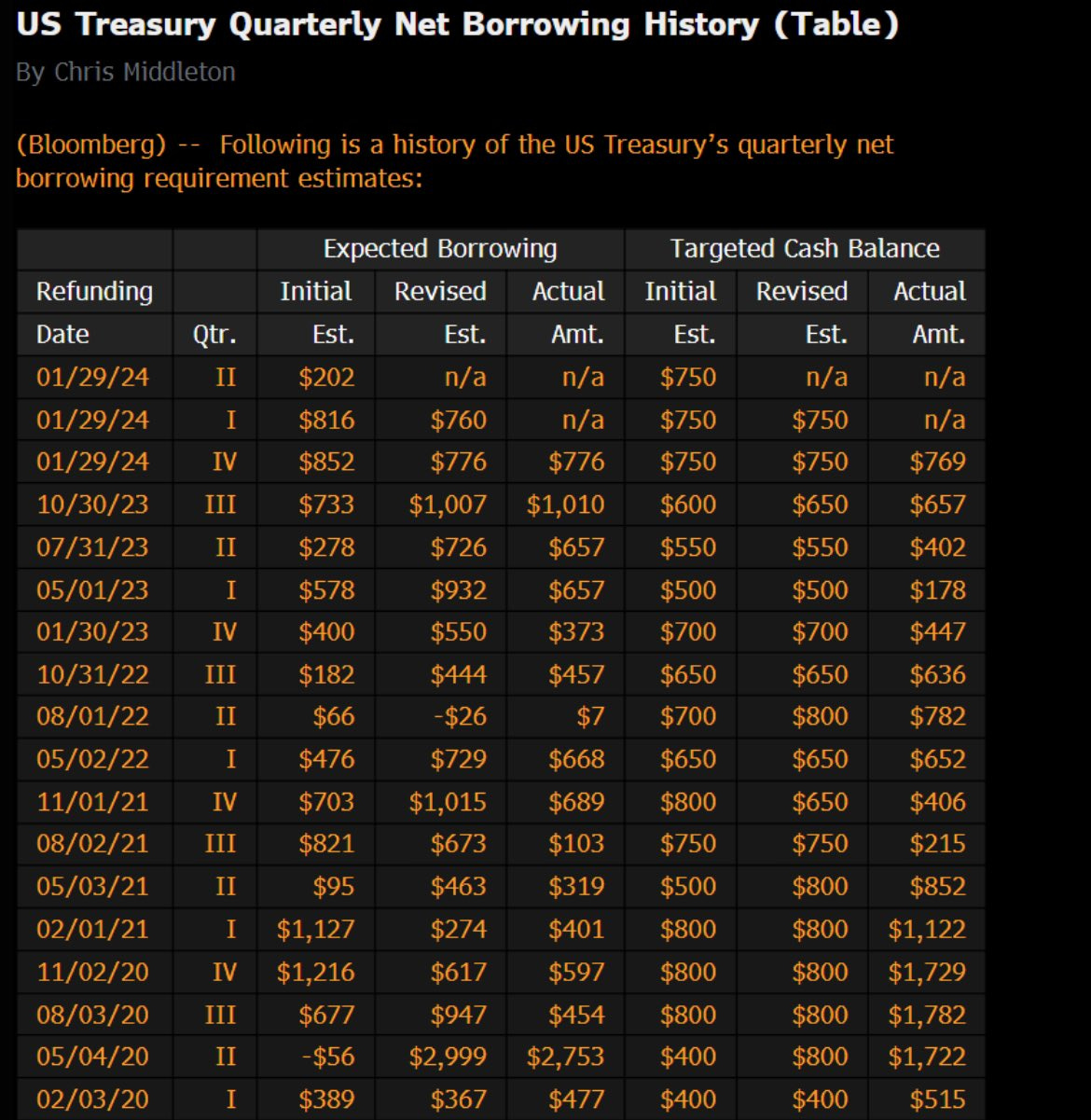

One of the interesting developments in monetary policy is the emergence of the Treasury’s Quarterly Refunding Announcement as an important news item. What used to be an obscure detail is now something that moves markets, as evidenced by John Authers ($) in this graph on Monday:

It’s also interesting that the market moved up on Monday after the release of the initial borrowing estimate at 3:00 p.m. As Craig Shapiro points out on X, the initial estimates are often “wildly” wrong and provide little guidance to the actual number:

When the actual issuance numbers came out on Wednesday morning, coupon issuance was increased a bit which was in line with prior guidance. It was higher than some of the most dovish expectations, however.

The key tipoff, though, was the statement that Treasury “does not anticipate needing to make any further increases in nominal coupon or FRN auction sizes … for at least the next several quarters.” That was a fairly strong signal to markets that the upward pressure on yields from ongoing increases in issuance is fading.

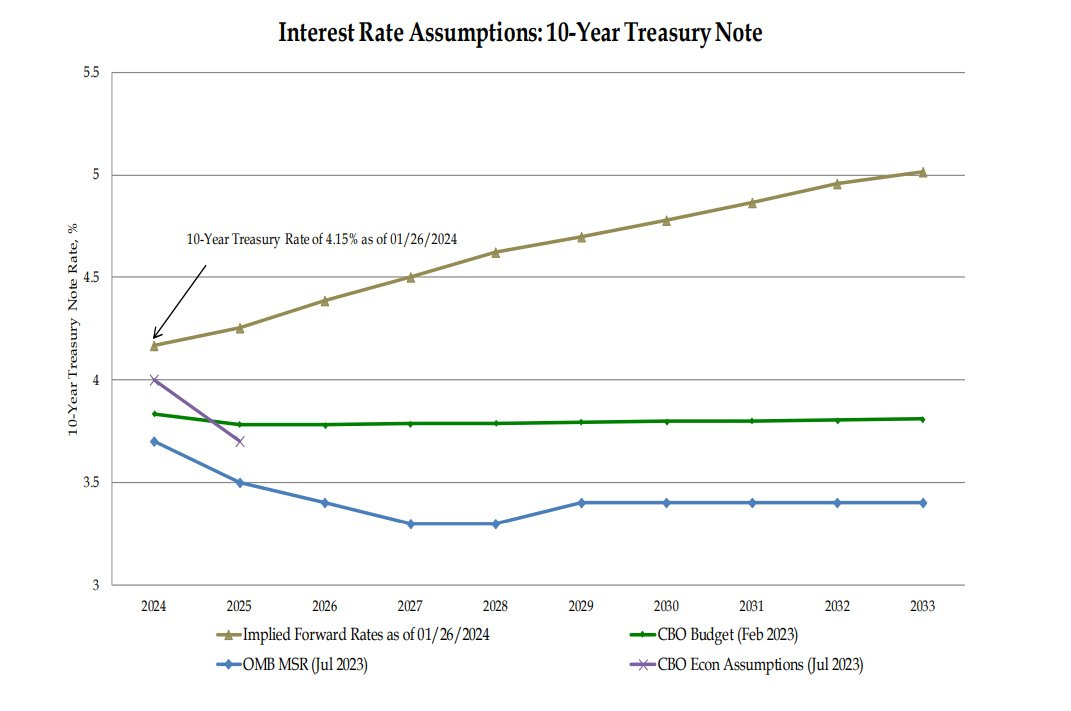

That is - if you accept Treasury’s forecast uncritically, which I don’t. For one, there is absolutely no indication that deficit spending is going to ease or that tax revenues are going to suddenly balloon. For another, Treasury has all kinds of self-interest in promoting such a story because it would ease financial conditions and create a nice backdrop to help Biden get re-elected. Corroborating this view, Stephen Miran illustrated on X how “projections are totally ludicrous if market rates stay at these levels”.

Finally, like the small print in a pharmaceutical commercial, the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC) quietly amended the expectation for future issuance by saying, “it may be appropriate over time to consider incremental increases in coupon issuance depending on how the current uncertainty regarding borrowing needs evolves.”

Perhaps I am being too suspicious, but it sounds to me like TBAC isn’t nearly as confident as Treasury is (at least in its public statement) about future coupon issuance needs and wants to indemnify itself. If that’s the case, and I suspect it is, then markets may condone lower bond yields for a while, but it will just be a matter of time before expectations are reset higher as higher financing needs are realized.

Investment landscape

While it can be debated how much power the Fed actually has to guide the economy, it is clear the market still listens carefully to what it has to say. As the timeline from John Authers at Bloomberg ($) illustrates, the 10-year Treasury yield didn’t really fall apart until after Powell made clear that a cut in rates in March was unlikely.

Increasingly too, the Treasury is getting in on the game of interventionism. As noted earlier, the last two Quarterly Refunding Announcements were market moving. Further, the announcement this week may prove to be also, but its effect was obfuscated by the news of New York Community Bancorp (NYCB). Regardless, it appears Treasury is also getting comfortable with the role of guiding outcomes in financial markets.

This creates a dangerous paradox for investors. If you don’t follow the guidance of monetary authorities, you risk getting run over. If you follow them too blindly, you risk taking on exposures that you know in your heart of hearts are not appropriate.

Implications

In a very basic sense, the decision by both the Fed and Treasury to engage so purposively in narrative (aka, “communications” strategy) should indicate financial markets are not as healthy as they could be. If they were, everyone could see for themselves; they wouldn’t have to be told. This alone should cause investors to be skeptical.

There are several other implications, however. For one, while it helps to understand broader public policy goals in order to frame the possibilities, it doesn’t make sense to exert too much effort trying to get in the head of Jerome Powell or Janet Yellen. It’s impossible to know exactly what they are thinking at any point in time and there are more valuable ways to spend one’s time.

More importantly is the likelihood the objectives of monetary authorities begin diverging from those of investors. To date, higher stock prices have helped facilitate a transition to a higher rate environment. Going forward, however, it will be progressively more important for funds to flow into bonds. Lower and/or declining stock values would facilitate that effort.

In addition, monetary authorities are increasingly subjected to real world constraints that significantly limit what they can accomplish with their limited set of tools. It’s one thing to keep rates low when there is no threat of inflation. It’s an entirely different thing to lower rates when inflation is already too high and there are clear risks to it going higher.

In general, then, it will be increasingly important to scrutinize monetary guidance and to judge its implications rather than following such guidance blindly. Otherwise, investors risk getting played. They risk being corralled into assets that help government but at their expense. In general, this suggests fading extremes in market narratives.

More specifically, this suggests reducing exposure to stocks and being wary of increasing exposure to bonds. With the primary policy goal now being to ensure higher levels of private demand for US Treasuries, that means making Treasuries look more attractive and that means making stocks less so. This is the way things work in intervention world.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.