Observations by David Robertson, 2/7/25

Another week and another flood of news to assimilate. Let’s dig in.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

Mondays are getting to be newsworthy days! This week we got hit with new tariffs on China, Mexico, and Canada. After throwing markets into a tizzy to start, a phone call in the morning with Mexico got tariffs pushed back a month and one later in the day with Canada also resulted in a one month delay.

Stocks recovered most of the losses by midday but weakened into the close. Stocks picked up again on Tuesday after the news on Canada got priced in. It was almost as if all the leaders already knew the script and simply read their parts.

Inflation

While there was a lot of commotion around tariffs this week, arguably the more important topic will be the effect on the economy. On this topic, Brent Donnelly lays out a nice, clear thesis on why he changed his mind on the inflationary impact of tariffs.

He started with the view that “Tariffs are bullish bonds because the Fed will look through them and the economic confidence damage is greater than any one-time price level change.” This was bolstered by the empirical evidence that “Almost every tariff announcement in 2018 and 2019 saw bonds rally.”

However, he came to realize the environment had changed:

But several years of high inflation triggered by the pandemic and a policy response that showered the economy with ultralow interest rates and fiscal stimulus have raised questions over whether the Fed could be as relaxed about an increase in prices. If the cement is wet, expectations of higher inflation in the future could sustain higher price growth.

He concluded: “Psychology has changed and tariffs will be inflationary. I think the key point is that inflation is a psychological phenomenon”.

Donnelly’s account highlights a couple of important lessons. First, it is counterproductive to be too dogmatic. The impact of tariffs on inflation (or almost any policy initiative on almost any economic measure) is not a function of a mechanical, deterministic relationship but rather is contingent on underlying conditions. When the facts change, so should the analysis.

Second, it isn’t just the facts of the analysis that count, but the perception of those facts, i.e., psychology. Several years of zero interest rates prior to the Covid pandemic helped anchor expectations of inflation at very low levels. During Covid, huge liquidity infusions and widespread supply constraints radically changed the psychology around inflation.

Looking ahead, while the Covid experience can still be plausibly characterized as a one-off, extraordinary event, it did reset expectations. Next time around, it won’t take nearly as much of an impetus for inflation expectations to adjust higher. Indeed, that may already be happening. As the graph below from the Daily Shot shows, inflation expectations have been picking up significantly since October.

Monetary policy

The Quarterly Refunding Announcement came out on Wednesday and for the most part maintained the same course set under the Yellen Treasury. It also maintained the same guidance: “Treasury anticipates maintaining nominal coupon and FRN auction sizes for at least the next several quarters.”

That said, the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC) itself gave a very different impression of issuance conditions:

In discussing issuance recommendations, the Committee uniformly encouraged Treasury to consider removing or modifying the forward guidance on nominal coupon and FRN auction sizes that has been in the refunding statement for the past four quarters. Some members preferred dropping the language altogether to reflect the uncertain outlook, though the majority preferred moderating the language at this meeting. Universally, the Committee felt that any shift in language should not be read to indicate an expected near-term increase in nominal coupon auction sizes, consistent with the TBAC recommended financing tables and Treasury’s objective to be regular and predictable. Members noted elevated uncertainty regarding macroeconomic developments and the fiscal trajectory …

This is interesting for several reasons. First, after publicly criticizing former Secretary Yellen for issuing a disproportionately small amount of longer-term bonds, new Secretary Bessent decided to maintain the same policy direction. Why did he change his mind? Maybe he discovered the funding challenge is harder than he thought?

Second, why would TBAC have more concern about “elevated uncertainty regarding macroeconomic developments and the fiscal trajectory” now with Trump in office? That outlook should only be more uncertain (than under Biden) if the Committee thinks Trump’s policies are going to make things worse.

We may have gotten a clue. Bob Elliott posted that “just after the election” central banks tested out “selling some of their 3.5tln in treasury bonds”. He continued that this foreign central bank selling “looks like the culprit” that moved 10-year Treasury yields higher post-election.

That presents another possibility for the Bessent Treasury’s surprising continuity: It knows it has a gun pointed at its head in the form of potential Treasury selling and that significantly limits its degrees of freedom. The fact the US dollar was down and gold was up after the announcement add credence to the hypothesis.

Politics and public policy I

There has been plenty written about Trump’s tariff policies this week so I don’t think it is useful to add yet another commentary to the list. What I do find interesting is the remarkably different reactions to it.

John Authers from Bloomberg ($) let his opinion be known in a piece entitled, “How stupid is this trade war? Let me count the ways”:

In sum, even though Trump has a mandate for an anti-globalist and protectionist policy, starting with the two neighbors [Canada and Mexico] maximizes the risk to US jobs and prices. It offers minimal prospect of stemming fentanyl, stirs the risk of more migrants coming from Mexico, and is minimally effective in reducing the trade deficit. The reason markets appear to hate this, and didn’t believe Trump meant it, is that it’s a terrible idea.

On the other hand, Alyosha ($) compared Trump’s first ten days to FDR’s first one hundred days of historic policymaking:

Whether history looks kindly on Trump’s onslaught in these early days of 2025, only time will tell. However, history will note his stunning level of preparation, transparency, and determination to provide relief and reform to a nation that voted for radical change.

Two smart people, two entirely different accounts of the impact of policy thus far. My sense is there are a couple of important phenomena here. One is that each political team still sees what they want to see; they effectively speak different languages. This is unfortunate because it makes the amount of common ground appear to be less than it is.

Another phenomenon is there appears to be a significant difference in the accounting for longer-term and less measurable consequences. While tariffs on Mexico and Canada may be viewed as a useful threat issued to achieve greater compliance on border control, those threats instilled a sense of unpredictability. As Martin Wolf ($) writes in the FT, unpredictability has costs:

A crucial objection to what Trump is doing is the uncertainty he creates. The decisions by Canada and Mexico to enter a free trade agreement with the US … were bets on policy stability. This is important for countries, especially small ones, and vital for businesses betting on reliance on foreign markets and integration into complex supply chains. Even unfulfilled threats are damaging. An inconsistent US is an unreliable partner: it is that simple.

The costs of that inconsistency are already being felt by carmakers, among others. From a separate story ($) in the FT:

“The mechanics of it [tariffs] are almost as bad, if not worse than the actual amounts because the accounting and book-keeping and paperwork requirements involved to ensure compliance are massive,” said Ian Henry, an automotive production expert who runs the AutoAnalysis consultancy.

Henry warned that the supply chain disruption could be worse than during the pandemic if a tariff war endured and carmakers were not able to provide enough financial support to keep their suppliers afloat.

So, there are also costs to tariffs, even if mainly used as threats for other objectives. For one, compliance efforts are massive. For another, tariffs create the potential for supply chain disruption at a scale akin to that experienced during the pandemic. Finally, unpredictability about policy direction and duration undermines efforts by manufacturers to invest in their businesses.

In short, tariff threats aren’t just innocent tools for negotiating, they also impose widespread collateral damage. It will be interesting to see the degree to which favorable interpretations of Trump actions change over time as the fuller costs of unpredictability are realized and the collateral damage accumulates. Alyosha is right on that count, only time will tell.

Politics and public policy II

A great deal of noise has been made about the Trump administration’s initiative to vastly shrink USAID and to move it under the purview of the State Department. Interestingly, top Democrats have “strategic reservations” about fighting back according to Politico (h/t Judd Legum):

When I asked veteran strategist David Axelrod whether Democrats were “walking into a trap” on defending foreign aid, he literally finished my sentence.

“My heart is with the people out on the street outside USAID, but my head tells me: ‘Man, Trump will be well satisfied to have this fight,’” he said. “When you talk about cuts, the first thing people say is: Cut foreign aid.”

Rahm Emanuel — the former House leader, Chicago mayor and diplomat — told me much the same: “You don’t fight every fight. You don’t swing at every pitch. And my view is — while I care about the USAID as a former ambassador — that’s not the hill I’m going to die on,” he said.

This raises several issues. Most clearly, there are Democratic causes, like USAID, that are just not popular across most of the country. That is a political reality Democrats need to acknowledge.

The lack of support begs the question of why such a program is so widely unpopular. One reason may be poor marketing. People just don’t know enough about the program or the benefits it provides relative to the costs. Whether that is due to arrogance or negligence is immaterial. If you are going to spend taxpayer money you have a responsibility to demonstrate you are spending it well. In too many cases that has not been done.

This puts Democrats in a tough spot. If they concede on too many issues, they look like feckless leaders who serve no purpose in forming meaningful opposition. If they fight on too many issues, they look like they are just fighting for the sake of fighting. At the same time, there are real issues of legality, constitutionality, and conflicts of interest, among others, that should be opposed. If Democrats can’t push back effectively on those issues, they will have lost their reason for being.

Technology

It’s easy to look at the DeepSeek AI proposition today and see how it could have a big impact on the industry. Interestingly, however, just over two weeks ago, the Economist ran a story claiming “OpenAI’s latest model will change the economics of software”:

one point of consensus has emerged. The [OpenAI] model, as well as its predecessor, o1 (o2 was skipped because it is the name of a European mobile network), produces better results the more “thinking” it does in response to a prompt. More thinking means more computing power—and a higher cost per query. As a result a big change is afoot in the economics of a digital economy built on providing cheap services to large numbers of people at low marginal cost, thanks to free distribution on the internet. Every time models become more expensive to query, the zero-marginal-cost era is left further behind.

No wonder Silicon Valley was freaking out about DeepSeek. Not only was the narrative of the end of the “the zero-marginal-cost era” completely upended almost overnight, but it was done so just as OpenAI was starting another funding round. Talk about killing two birds with one stone.

Or was it? Rusty Guinn from Epsilon Theory ($) details how some of the questions that arose during the week shifted the narrative:

Could DeepSeek have been lying about how easily they trained R1 to spook US markets and steer its competitors in the wrong direction? Could all of this be a psy-op designed to give China an edge as the world’s AI leader? Could it be a CCP ploy to extract data from private citizens in the west while our lawmakers are focused on finding the most politically connected tech oligarch to get a sweetheart deal for TikTok?

Perhaps more interestingly as the week went on, basically all of the fundamental narratives faded in concert. That is, the event became less about the framing that chip manufacturers would be the hardest hit, less about the impact on LLM competitors, and less about the threats to the AI stock boom more broadly. Instead, the narratives framing the DeepSeek-R1 launch to be about the threat it represented to national security, about a psy-op lying about how cheap it was to develop, and about the need to ban it all rose in relative density, even if they still remain in the background.

What does this mean for AI and Big Tech in general? First and foremost, it means the Common Knowledge that Big (US) Tech dominates AI is being challenged. Clearly, there is competition. It also means the path to dominance is not necessarily paved with exclusive access to high-end semiconductors and a bucket of cash. Again, it’s a much more open race than that would suggest.

Finally, once Common Knowledge changes and a narrative breaks, things can change quickly. Just think back to Joe Biden’s performance in the presidential debate last summer. That is the risk facing Big Tech right now — when everybody knows that everybody knows — that things have changed.

Investment landscape I

How Silicon Valley turned China into its lifeline ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/94111c2c-8ec3-43a4-a71a-d73431b0325d

there’s an excellent case to be made that Eric Schmidt is the most influential American foreign policy thinker of the early 21st century … Over a few years, Schmidt reshaped America’s understanding of national security … Now that economic neoliberalism is moribund, I think that there is a New Washington Consensus, which Schmidt has done more than anyone else to shape … Instead of multilateral institutions, you should now look to the assumptions of the emerging mind-meld between Silicon Valley and national security policymakers, to see how America wants to shape the world.

Schmidt repurposed “competition” [between US tech firms] to mean US-China competition. I am not saying he was motivated simply by the desire to help his Silicon Valley peers. I think he was — and remains — sincere in making the national security case for big tech … Either way, 2017 was the year that Washington reimagined Silicon Valley’s bad boys as shields against China. Far from regulating big tech, Washington resolved to treat the west coast titans as weapons in democracy’s arsenal … The view was that China and the US are in a race to see which could attain artificial general intelligence (AGI) first.

This is fascinating not least of which is because it explains so many things. Why haven’t Big Tech firms suffered more backlash due to obviously harmful effects on society? Because their narrative was changed to be one of critical value for national security. Why has artificial intelligence become such a hot topic? At least partly due to its role in keeping score in the competition with China.

Russell Clark ($) has also picked up on the anomaly of Big Tech exceptionalism, but from a slightly different perspective.

One thing that DeepSeek has shown is that US tech is not really about tech - but more about building and maintaining monopolies. I for one still remain staggered at the pricing power that Meta has.

What I am seeing now is that tech is now causing cost pressures - and it is mainly falling on other businesses.

This too helps explain a lot of things — such as the hugely differentiated performance of Big Tech vs. small cap stocks. Small caps are the ones getting gouged on pricing. It also explains why price pressures are inflationary in the US but deflationary in China. Because China has clamped down on tech monopolies and forced a more competitive environment while the US continues to protect its tech monopolies.

PauloMacro ($) also had a similar observation:

The old chips narrative was “China is coming for mass market/analog chips, and semis are screwed because when China gets in on something margins go to nearly zero, but NVDA, its high end GPUs, and CUDA software-on-a-chip are…Exceptional.” China just showed the world that those chips are nice to have, but you don’t really need all that to build a top AI mousetrap. It is an existential Missionary Statement, and a hell of a realization moment

So, at a time when retail investors continue to pile new money into the space, and many investors consider Big Tech “safe”, the narrative on Big Tech is clearly breaking and China has both the means and the motive to undermine US tech. PauloMacro sums it up by saying, “the sentiment and narrative is all wrong.”

Investment advisory landscape

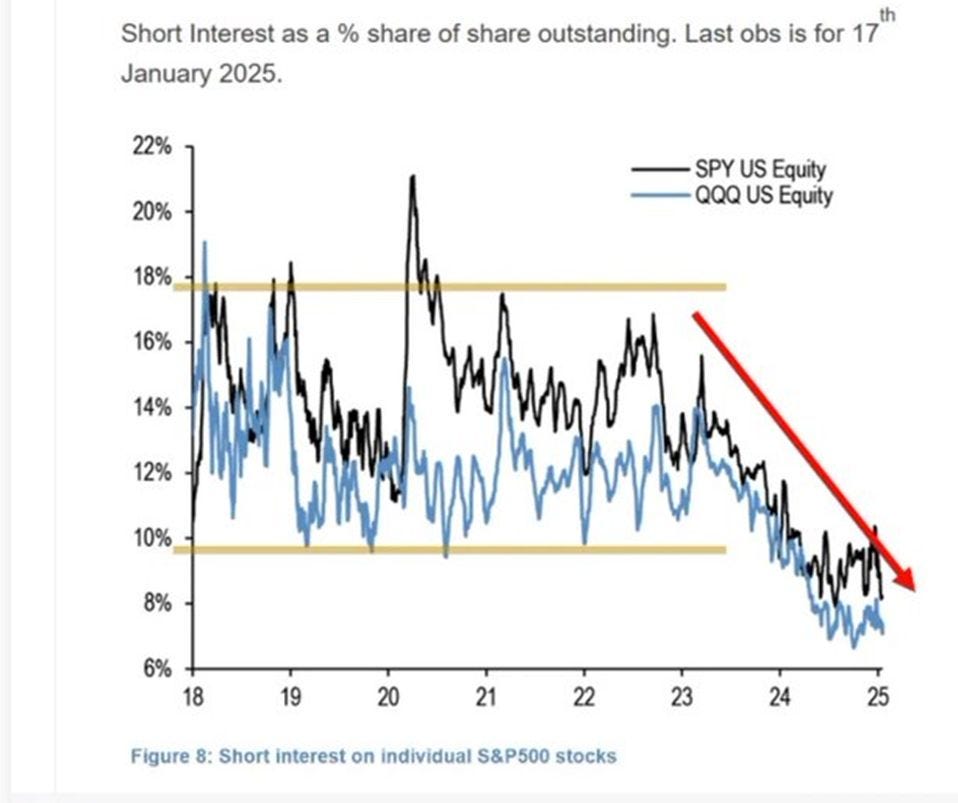

Bob Elliott recently posted, “Short interest is dead,” and appended the following graph. True enough, the last two years have been especially difficult.

What shouldn’t be lost in the message is that the landscape had already been extremely challenging for short sellers. Public policy support and lax enforcement helped keep businesses afloat whether it was deserved or not. When Jim Chanos shut down his fund in 2023 I wrote, “speculative sentiment continues unbridled. As a short, you can be right on the analysis and still lose money.”

Along the same lines, Jim Bianco recently noted, “BAUPOST CLIENTS PULLED $7 BILLION SINCE 2021 AFTER POOR RETURNS”. He goes on to explain to those unfamiliar:

This is the firm run by Seth Klarman. He is on the Mount Rushmore of investors in our lifetime. And after Warren Buffett, he might be this generation's second-greatest value investor … Considering that a big chunk of his assets are his and his partners', this might be most of his outside money. Take this as another indication of how out of favor value investing has become.

Bottom line, these aren’t the kinds of things you see at the beginning of a huge bull market. They are more like the last capitulations right before the market turns.

Implications

With an extra week to ruminate on DeepSeek and extra time to ponder the investment landscape holistically, it looks more and more like pieces are falling into place regarding the vulnerability of Big Tech and US stocks in general. In the latest market review I noted:

But there is something wrong with overly optimistic sentiments that overwhelm objectively bad risks. Bond investors have learned this lesson over the last three and a half three years. Stock investors are up next.

I’m sticking with that assessment.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.