Observations by David Robertson, 3/10/23

As Tier1Alpha described in their sitrep yesterday: “make sure to note that you were there when the rhetoric between the US and China accelerated sharply and an intelligence report was released highlighting Putin's increasing reliance on the threat of nuclear weapons. And that markets completely ignored it.” There has been an eerie calm in stocks despite some pretty ominous rumblings.

Well, that didn’t last more than a few hours until SIVB got walloped for a 60% loss Thursday and concern immediately spread to the broader market with the banking sector getting hit especially hard. Increasingly it looks like the market’s calm demeanor belies some deep anxiety.

If you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

There are often situations where you just know a group is up to no good. Retail investors have been that group for the last couple of years. They cycled through SPACs, and meme stocks, and options, and crypto, and bankrupt companies. Now they are on to TSLA. Just can’t get enough it seems. Let’s see how this works out.

Jerome Powell testified to Congress this week and said pretty much what he has been saying for the last several months. Stocks dropped by 1.5% but stayed well-anchored around the 4000 level. The biggest effect was on rate expectations which immediately shot up. The gap between stocks and bonds is now growing quite large: Continued increases in rates just aren’t affecting stocks - at least not yet.

Credit

A couple of important points come out of this Twitter exchange. First, it has been something of a puzzle as to why credit spreads have remained so low, even as rates have risen. @Stimpyz1 offers a perfectly reasonable hypothesis: The low credit spreads are not any kind of reflection of economic activity but rather a reflection of market structure. With ETFs dominating the market and a handful of issues dominating those funds, low credit spreads just don’t tell us anything very meaningful. Certainly not anything broadly applicable to the market.

Interestingly, the marker @Stimpyz1 points to is new issuance, and that is “down 85% YoY”. This approach allows the Fed to shut “down the sausage factory without blowing up existing portfolios”. Can’t complain about that.

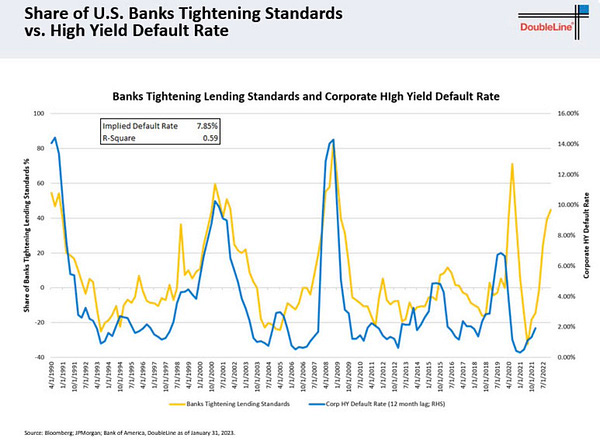

This tweet also sheds some light on the credit issue. Current default rates are still exceptionally low, but banks are beginning to tighten lending standards considerably. Since these two metrics are historically correlated, the tighter lending standards suggests there might just be a time lag.

The broader point is the same: many conventional navigational tools are not working nearly as well as they used to. In some cases, they are even giving off exactly the wrong signals for investors. Credit spreads and default rates count among them, but there are plenty. Investors who don’t actively refine their dashboards are likely to get in an accident.

Housing

Really nice thread here on housing. The main message is residential housing construction is a key economic indicator and it is right at the threshold of peaking. This peak is taking longer to develop after the turn in building permits this cycle but that is likely due to pandemic conditions that caused homes to remain under construction for longer than normal. Just because the turn hasn’t happened yet doesn’t mean it isn’t coming. Watch out for economic growth to start slowing.

Public policy

Joe Biden teaches the EU a lesson or two on big state ‘dirigisme’ ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/ef04638d-e4b6-4bcc-86c9-fac2cc04d198

In case you hadn’t noticed, an incredibly bold experiment in social dirigisme is unfolding not in France, where linguistically and spiritually it belongs, but in the land of the free.

What US commerce secretary Gina Raimondo has outlined is a far-reaching attempt to bend employer behaviour, not only in the field of industrial and financial strategy — chipmakers must agree not to expand in China for a decade and refrain from stock buybacks — but also in how they treat their staff.

According to wikipedia, dirigisme “is an economic doctrine in which the state plays a strong directive (policies) role contrary to a merely regulatory interventionist role over a market economy”. This is in contrast to laissez faire in which economic actors are largely allowed to act freely.

It is interesting to see how this movement is coalescing around increasingly muscular industrial policy in the US. Written into the Chips Act, for example, is a provision that applicants will provide “affordable, accessible, reliable and high-quality child care”. Those applicants are also “‘strongly encouraged’ to sign collective bargaining deals with unions ahead of building new plants”.

One thing to note is while many items on the progressive wish list did not make it into the Inflation Reduction Act, they are showing up in other places like the Chips Act. These policy ideas are not dead; they are just taking a slightly more circuitous route to implementation.

While many of these policies are quite arguably reasonable, there is room for plenty of debate as to whether they should be “directed” by government or not. The fact that government is becoming more directive sends a strong signal for free market enthusiasts to update their mental models for the new political reality.

The emergence of increasingly directive behavior on the part of government also speaks volumes to the ongoing competition between labor and capital. I have argued the pendulum seems to be swinging back in favor of labor over capital - and this newfound dirigisme is strong evidence of exactly that.

Geopolitics

West Point Paper by Michael Kao

https://urbankaoboy.substack.com/p/west-point-paper-part-14

The ”top-down” interpretation of Bretton Woods suggests that it acted like a “Trojan Horse” for the world to get addicted to USD trade because it was backed by gold, only to then abandon that backing with the Nixon Shock of 1971. History suggests, however, that trust in the USD went well beyond its gold backing long before the Nixon Shock.

It has become popular for detractors of the US to cite the burgeoning Debt/GDP ratio and the twin deficits as reasons for the imminent demise of USD hegemony and the consequent loss of “exorbitant privilege” … While it is fair to critique the ballooning liability side of the US balance sheet, few discuss the unparalleled geographic assets that the US boasts on the left side of the national balance sheet. These assets confer significant economic benefits and the ability to project power far and wide. In many ways, these endogenous advantages have allowed the US to make sometimes grievous policy errors and still allow ample margin for course correction …

When a paper entitled, "US Dollar Primacy in an Age of Economic Warfare," is presented at a West Point symposium, it becomes very clear very quickly that economics and the role of the US dollar (USD) are of utmost importance to national security. It also becomes clear that military leadership is actively engaged in strategy and thought leadership for the purpose of ensuring national security.

One of the interesting perspectives that comes out of the paper is the notion that USD was firmly established as the Global Reserve Currency (GRC) well before Nixon broke its backing with gold in 1971. Not only had USD become the “best alternative [to Sterling]”, but its adoption “grew organically with the rise of Eurodollar banking throughout the 1950’s and 1960’s”. As it turned out, “the global monetary system’s need for additional liquidity exceeded what the theoretical gold backing could provide”. In short, USD earned its role as GRC and continues to earn it today.

Another interesting consideration is economic warfare in the form of deploying a strong USD strategy. Kao writes:

Rather than resorting to kinetic means, economic warfare can be an effective way to sow chaos and force the enemy into an economically ruinous defense strategy – especially when the “weapon” is masked as domestic monetary policy rather than overtly hostile financial sanctions. The presence of persistently high inflation at a level not seen since the 1970’s presents an interesting geopolitical opportunity for the US to pursue a strong USD policy to not only fight inflation domestically but to advance geopolitical interests at the same time – in effect targeting “two birds with one stone.”

Accordingly, the US could impose crippling pressure on China, Russia and other geopolitical rivals by maintaining a strong USD, while at the same time maintaining plausible deniability that such policy is nothing other than a domestic effort to control inflation.

I think there is a lot to this. Insofar as this is the case, it is very dangerous to bet against USD because you are also betting against US national security. It also means that while the Fed is likely trying to manage inflation, it is national security that is really driving the train.

One implication is it doesn’t make any sense to look into Jerome Powell’s eyes to try to “see his soul”. He is mainly just acting as an agent for a greater cause. This may very well cause the Fed to keep rates higher for longer. Another implication is economic outcomes will revolve around USD strength. This will help mitigate inflationary pressures in the US and will put significant pressure on China and Russia to choose between higher inflation and slower growth.

Investment landscape

Interest rates are among the most important investment metrics because they represent the price of money. Longer-term rates, specifically the 10-year US Treasury rate, are also extremely important because they are the basis of establishing value for virtually every longer duration investment. These two tweets stand out for highlighting a possibility very few are discussing: The possibility that long rates can go much higher yet.

The media seems to be focusing almost uniformly on the fact that long rates are currently lower than short rates. That misses some really important possibilities, however. What both @PauloMacro and @hussmanjp pick up on is the term premium is unusually low. While long rates can and do vary relative to short rates, the current differential is unusually low.

One reasonable possible explanation is collateral shortage. There just aren’t enough long bonds around so investors bid them up, sending yields lower than they otherwise would be. Certainly possible.

Regardless, it is interesting both views anticipate significantly higher long rates. With just a normal term premium of 1%, the 10-year would go above 5%. Simply re-establishing a normal term premium and a normal relationship with inflation, GDP, and T-bill yields would push long rates over 5%. This compares to current rates hanging around, but still below 4%.

I think long rates are more likely to continue higher than not. Insofar as this does happen, it will put another dagger in real estate, it will punish bond portfolios, and it would effectively kill off financial engineering in its myriad forms. It would also send a strong signal that this isn’t just a bump in the road and investors can no longer rely on the Fed “put”.

Asset allocation

Great Expectations by Michael Green

https://michaelwgreen.substack.com/p/great-expectations

But the much bigger issue with these [common asset allocation] strategies is their over-reliance on historical return expectations.

But that’s not the real kicker. The really important number is the percentage of contributions (new flows). Target Date Funds now capture over 60% of all new assets. In other words, the majority of assets no longer CARE what valuations (or bond yields) look like when allocating to assets.

However, something quite different occurs when we introduce passive manager behavior to the model. Remember that passive managers run on a very simple algorithm, “Did you give me cash? If so, then buy. Did you ask for cash? If so, then sell.” There is no consideration of value — in fact, the market cap weighting methodology does the opposite by adding MORE of each marginal flow to the most richly valued stocks while reducing marginal investment in stocks that fall in price. The net effect of passive gaining share is to push the markets away from the historical equilibrium. As valuations are pushed higher, returns are anomalously high for any given valuation.

While Michael Green has expounded on all of this before and I have commented on it several times myself, these points are worth repeating because they are probably the most important things for long-term investors today to be aware of.

Number one, most of the return expectations used by most investment product vendors rely too much on historical returns which provide overly optimistic estimates for the future. As such, they vastly increase the chances retirement income/security will fall short of expectations.

Number two, the proliferation of passive investing and target date funds for retirement have combined to make a dominant share of new flows into financial assets completely insensitive to price. This has completely undermined any ability by markets to mean revert organically.

As Green concludes, “So we’re left with a market that is now veering wildly off course. Instead of allocations to equities falling with rising valuations, they are rising.” Further, while valuations are veering wildly off course, the market has been excised of the mechanisms that used to correct such deviations.

Implications

One important implication of this increasingly passive-driven investment world is that many indicators just don’t contain the same degree of information content any more. Credit spreads used to be an indication of credit risk as assessed by cash investors; now it is a representation of a handful of companies that dominate credit ETFs. Stock valuations used to indicate market extremes; now they simply corroborate the fact that most stock flows are not sensitive to price.

Another implication, and it is a big one, is that many well-worn investment practices are not well-suited to the current investment landscape. Return expectations based solely on history are quite likely to be overly optimistic. The increasing dominance of passive strategies is causing valuations to veer “wildly off course”.

The only antidote for these problems is to do something different. That requires making more thoughtful efforts to estimate future returns and allocate assets according to opportunity, not availability. It’s not super hard to do, but it does require an intentional effort.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.