Observations by David Robertson, 4/26/24

It was a busy week and an eventful week. Let’s dig in.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

The momentum factor (ETF MTUM) had been a key driving force for stock returns this year. After reaching a plateau in March, however, the factor turned down through April. Starting on Monday that was all “bygones” though as momentum surged back up on the strength of crashing volatility and “buy-the-dip” buying frenzy.

Another market dynamic of note has been the strong US dollar (USD). As Brent Donnelly notes in his last Friday Speedrun! report:

In fact, I would be more inclined to think we stay in a rangebound regime for FX, and I prefer to be short USD here, not long. There are a few reasons for this, including positioning.

We have been running a weekly FX positioning report at Spectra since October 2022 and the readings this week are the most extreme so far. Both long USD momentum and long USD positioning have touched never-before-seen levels. This touching of the extreme does not have a perfect record in forecasting USD turns, but it’s pretty close as it’s identified an important turning point four out of five times.

Has USD been strong for good reason? Yes. Is there good reason to believe it may take a breather for a while? Also yes.

In other news, the S&P Global Flash US Composite PMI® came out on Tuesday giving markets a boost by showing a declines in services growth which sparked renewed speculation the Fed will need to cut rates soon. As Bob Elliott was kind enough to point out: “This is your irregular reminder that the PMIs are total garbage. They should be ignored by those trying to understand the economy and faded by those trading markets.”

On Thursday, GDP came in weak and personal consumption expenditures (PCE) came in hot. Weak growth and higher inflation shine a bright, hot spotlight on the challenges facing the Fed.

Finally, it was also a big week for corporate earnings. Tesla popped on terrible results which was partly a function of already being down about 50% year-to-date and partly an indication of the faith investors still have in promises about the future. On the other hand, Meta got punished after discussing much higher spending plans for things like artificial intelligence. After the close on Thursday, Google and Microsoft both reported strong results. Across the broad range of companies I sample, which tend to be more in the mid-cap range, revenue growth looked pretty flat. A mixed bag overall.

Economy

America is uniquely ill-suited to handle a falling population ($)

Between 2010 and 2020 the number of people in the country grew by around 7.4%. That was the slowest decade of growth since the Great Depression (when the population grew by 7.3%). In the 1990s the growth rate was 13%. The main culprit is falling birth rates. The total fertility rate—a measure of how many children a typical woman will have in her lifetime—was steady or rising for 30 years from the mid-1970s. In 2008, however, it fell below 2.1, the level needed to keep the population stable, and has since declined to 1.67 (see chart 1). If it remains below 2.1, only immigration can keep the population growing in the long run. Yet net immigration, too, has been falling since the 1990s.

But America is different from Britain or France in that its population is much more prone to move around the country. Some parts of America are extraordinarily successful at attracting new people.

Shrinking is bad for many reasons … But the biggest problem is that, once a place starts shrinking, it can set in motion reinforcing cycles that accelerate the decline. For example, when there is far more housing available than people to fill it, the result tends to be a collapse in the value of homes. If it is severe enough, landlords and even homeowners stop maintaining their properties, because the cost of repairs is higher than the return they will generate. As the resulting blight spreads and neighbourhoods begin to feel hollowed out, the incentive to stay is reduced even further. This is what is called a death spiral.

This article by the Economist touches on a number of issues that are incredibly relevant to the economy and investment landscape, but rarely hit the radar of daily news items.

For one, population growth in the country is terrible; the ten years from 2010 to 2020 “was the slowest decade of growth since the Great Depression”. I don’t think this is very widely understood or appreciated.

Further, when growth is so low, it effectively becomes a zero-sum game. This means growth in one area must almost certainly come from growth in another area.

This leads to a serious problem: Declining population in an area often triggers a vicious downward spiral. Because cities rarely reduce “the public sector in line with the population,” taxes go up and public services go down. As a result, the people who can leave, do.

The result is a country that is better described economically as being bipolar. It has regions that are growing and that are extremely successful, but is also has areas that are dying and have little hope of turning around.

The economic incongruence also leads to political incongruence. According to the Economist, “Of the counties that lost population in the decade to 2020, 90% voted for Donald Trump in 2020.” The policies and rhetoric that enliven one environment are increasingly anathema to the other.

This background provides a useful guide for better understanding partisan politics and for reformulating public policy. It certainly highlights how a number of policies that have been so beneficial to some have been equally harmful to others.

Demographics

Bruce Mehlmen puts out a short list of graphs and charts each week that highlights interesting aspects of the political landscape. This past week he put out this little tidbit:

Is America Waging a “War on Its Young?”: Why is the U.S. the 10th-happiest country in the world for people over 60 but only 62nd-happiest for people under 30? Have we “broken the social contract that binds America: Work hard, play by the rules, and you’ll be better off than your parents were?” Thought-provoking piece by Scott Galloway (click on chart to read).

The table highlights the massive differences in what the “social contract” actually is to different generations, especially in regard to college education and homes which comprise important elements of the “American Dream”.

The same phenomenon was captured in a slightly different way by Vincent Deluard on X: “

Since 1980, the ratio of household net worth to the US median wage has increased by 370%. This is the single most important chart for finance, economics, and politics.

He goes on to say, “After 50 years or so, inequalities feed populism and anti-social behaviors because the young and the poor feel that the system is rigged against them (and it is)”.

The main point is to highlight the historical policy of favoring “capital” over “labor” has consequences. One consequence is to expand generational inequality. By extension, that increase in inequality also foments political discontent.

While pro-capital sentiment has been unusually strong in the US, that has not always been the case. Further, both major parties are now reacting to the discontent by leaning in a more populist direction. That said, the roots of pro-capital policy are deep. It will be very interesting to see whether some kind of awkward balance is maintained between labor and capital or if labor eventually wins out.

I’m betting on the latter, though the awkward balance may be maintained through the election. Political trends like this tend to run in long (i.e. multi-decade) cycles and capital has dominated for over forty years. It’s time for a change. If I’m right, it will be tough sledding for financial assets, but it should be good for worker wages and consumer spending.

Geopolitics

The fireworks between Israel and Iran have garnered the majority of geopolitical headlines the last few weeks. While this obviously presents significant risks, it is also important to note that it is not inherently a threat to the global order unless it serves as a trigger for broader conflict.

The bigger risk may be in distracting attention away from the feature geopolitical presentation: The heightening tensions between China and the US. This, after all, entails a struggle between two superpowers that echoes around the world. Further, both are vying to shape and control the future “operating system(s)” for economics, finance, and geopolitics.

Importantly, major components of the plans are incompatible with one another. The ongoing struggle, is likely to shape economic, market, and geopolitical outcomes for decades. Or, as Paul Tucker stated in the FT, “I do think it would help if economists, business people and financial market participants made more of an effort to recognise the profound shift in the geopolitical backdrop.”

Among other things, the heightening tensions introduce a great deal of uncertainty to the landscape. Policy moves by either China or the US must be considered in the context of possible reactions by the other. Assumptions about what either side wants are unknowable to a great degree and may change at any time based on context and changing priorities.

For example, many observers assume China will need to devalue the yuan, but there are compelling arguments as to why it may actually prefer to strengthen the yuan. In addition, many observers (myself included) assume the Biden administration will boost fiscal spending in order to boost growth going into the election. While that’s probably a good assumption, it may not take a lot to quickly pivot to more of a wartime stance.

In short, while there are lots of bright shiny objects to get distracted by, it’s best to keep focus on the big honking geopolitical problem and that is China vs. US.

Monetary policy

Even though interest rates still serve as an important signal for market participants, broader measures of liquidity have taken on a much larger role. As the Fed and Treasury have started working much more closely together, however, the task of projecting liquidity has gotten more challenging. Mainly, there are a lot more moving parts.

One of those moving parts is motive. What does the Fed want? What does Treasury want? They can be different things at different times. Broadly, I think the Biden administration has preferred a strong US dollar strategy in order to squeeze liquidity to its primary geopolitical rivals China and Russia. Of course, a strong dollar also mitigates the impact of inflation in the US as well.

A problem with a strong dollar, though, is that it hurts allies as well as enemies. Recently, some US allies have expressed their displeasure with the strong dollar. Brent Donnelly summarized:

Adding to my view is a chorus of pushback on the strong USD by officials in Japan, Korea, Sweden, and elsewhere. When all the global policymakers fall in line on currency policy, it’s important to take notice. This is exactly what happened when the dollar topped in September 2022 and October 2023.

Adding to the difficulty in analyzing liquidity is the growing awareness of liquidity as a key driver of asset prices. Widespread discussion of the Treasury’s QRA (Quarterly Refunding Announcement) next week is a good indication of this growing awareness. Only in the last year or so has this announcement been widely recognized outside of bond trading circles.

With increasing awareness of liquidity metrics by market participants comes increasing awareness of monetary authorities of that awareness. In short, those authorities can use the heightened awareness to their advantage. I think this is happening.

As a result, while I still believe liquidity is key driving force for markets, I am increasingly inclined to believe the exercise of trying to forecast liquidity is not very useful. There is too much we don’t know and too much that is arbitrary. To paraphrase six-term senator from Montana Charles F. Meachum (Shooter), “Liquidity is what monetary authorities say it is”.

One thing analysts can do is to appreciate there is nothing easy and no foregone conclusions to the monetary mess we are in. While the idea of a “soft landing” is still being tossed about, it’s important to understand that regardless of the quality of the landing, there is still a bomb on the plane in the form of excess money.

The massive amounts of money that were created during the pandemic are still out there. First, they were effectively sequestered in the Fed’s reverse repo program (RRP). Then they were transferred into Treasury bills that could be used to purchase (and boost) financial assets.

Now, there are a lot of highly valued assets that can be converted into “things” by way of higher purchasing power. As Conor Sen posted (h/t PauloMacro) there is distinctly potential for more inflation:

If we ever get a proper interest rate cutting cycle (100bps+), there are going to be so many households with sub-40% LTV mortgages looking to cash out or trade up that there won’t be nearly enough high-end homes or $50,000+ trucks/SUV’s to meet demand.

In other words, there is a lot of latent inflationary pressure in the form of inflated asset prices — like homes (and stocks!) that can and will be converted to other things when the opportunity presents itself. In short, inflation ain’t over.

Investment landscape

The world has changed, a lot ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/56ba5db3-d956-4004-8fe8-6c118be72d00

The world US investors face is very different today. But the key question is whether we will revert to the old status quo. Rob and I have wrestled with this constantly. I used to believe the old world would return eventually. The fundamental forces behind low-and-falling interest rates were, I thought, powerful and long-lasting: ageing populations, poor productivity growth, inequality and heavy demand for safe assets (better known as Ben Bernanke’s “global savings glut”). The pandemic was a big shock but was, in a word, transitory.

Today I’d take the other side of the argument:

Since 2021, US interest rates have risen higher and for longer than almost anyone expected. When the consensus is repeatedly wrong in one direction, that tells us something.

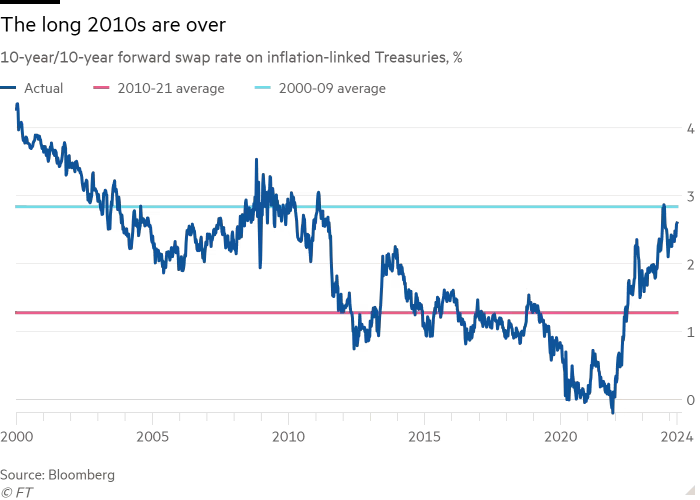

Long-term market expectations have come to recognise a regime change. Far-reaching measures, such as the 10-year/10-year forward swap rate on inflation-linked Treasuries, gives a sense of the market’s view on long-term real rates. On that measure, we are leaving the 2010s behind:

This is a nice summary of the landscape by Ethan Wu in his farewell to the FT. It captures both the important evolution of the market over the last few years and the kind of change in perspective that arises from thoughtful consideration.

Yes, there were initially reasons to expect a quick return to status quo after Covid. However, countervailing evidence has been accumulating ever since and now points more clearly to a fundamental change. As Wu states, “Rates will only return to 0 per cent in a true crisis.” Otherwise they will remain materially higher.

The sooner investors embrace this new reality, the sooner they can construct the right portfolio for it — and the less likely they will get caught holding the bag of too much risk.

Gold

This graph from Marin Katusa is a good illustration of where things are with gold right now. While the price of gold is making a solid move up, gold ETF assets are plumbing twenty-year lows. Clearly, whatever memo gold bullion buyers got has not been received by retail investors yet.

Total Gold ETF Assets under Management is at its 4th lowest point since 2005. Based on the past flow data, these extreme lows marked turning points with gold prices rallying. Retail and generalist funds are not participating... yet.

One obvious point is gold prices are being driven by investors in the East, primarily China. It would behoove Western investors to understand the dynamics behind this.

That highlights a second point: US investors are acting as if they are almost completely oblivious to events in other parts of the world — events that can and most likely will blow back on the US itself.

Part of this is due to an overwhelming faith in tech stocks and part of it is due to a US-centric view of the world. Regardless, it is striking to observe such a glaring opportunity.

While gold took a bit of a break this week, newbies are missing the degree to which gold was under-followed (due to the fascination with tech and crypto, among other things) and the magnitude of the upside as the global order evolves. It will take a long time to catch up. The pop in Newmont after earnings on Thursday is just a beginning.

Implications

One of the most striking characteristics of the investment landscape is the disparity between different perspectives/mental models of the world. Whether it is short-term vs. long-term or US-centric vs. global, the differences between world views could hardly be greater. This presents an unusual opportunity, but also an unusual risk.

The opportunity is to step back, take some perspective, observe all the little pieces of evidence of the evolving geopolitical, economic, and financial landscape, and to take measures to adapt to them. As I have reported many times, this mainly involves de-emphasizing US stocks and bonds, including a healthy allocation to gold, and finding a variety of other uncorrelated return streams.

The risk is to fail to consider the changes in landscape as being both durable and meaningful and to keep chasing US large cap tech stocks. This doesn’t need to involve any serious act of commission. Simply remaining impervious and/or oblivious to the fundamental changes will be sufficient to cause great harm. As a former boss of mine was fond of saying, “Sometimes it’s what you don’t do that kills you”.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.