Observations by David Robertson, 4/28/23

Since the Fed started raising rates last year it has felt like a waiting game for the economy to crash and the Fed to quickly reverse its course. We’re still waiting.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

OK, it was probably me. Just after I posted the graph below from themarketear.com ($) entitled “massively unchanged” on Tuesday, everything fell out of bed. The S&P 500 dropped 1.4% and VIX shot up from 17 to 19 1/2. So maybe earnings are starting to have an impact or concern is starting to mount regarding the debt ceiling. Or maybe not. The market was up 2% on Thursday. Tier1Alpha says, “It appears the era of consolidation has come to an end.” So there you go.

Either way it is feeling more like the (mostly) calm before the storm than clear sailing.

One phenomena that has been taking off is 0 day to expiry (0dte) options - which I have mentioned before. Now, to complement that trend, CBOE Global Markets has rolled out a one-day volatility index. As Almost Daily Grants (Monday, April 24, 2023) describes:

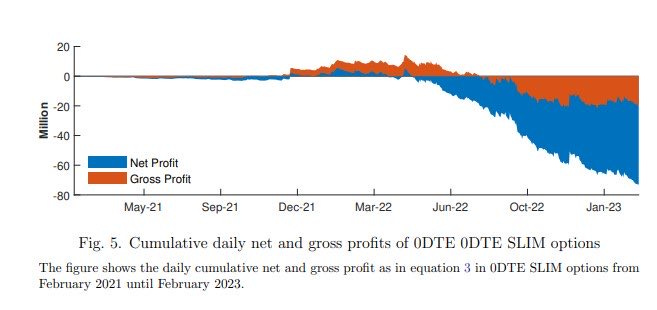

That migration towards ultra-short-dated derivatives has proven to be less than lucrative for the buyers. A study released this month by a trio of researchers at the University of Münster in Germany finds that individual investors have collectively lost an average of $358,000 per trading session wagering on zero-day options going back to May 2022. Those impatient day traders have lost money on a net basis every month since CBOE expanded S&P 500 options expiration to every business day in spring of last year. “Should daily expirations be rolled out for single equity options, the potential losses that retail investors face are amplified,” the paper concludes.

The phenomenon is more impressive when depicted graphicly (below) as done by Methor Q. AnilVohra1962 points out, this pattern creates “an options sellers fantasy come true”. In short, this is what Wall Street does best - finding new and innovative ways to separate investors from their money.

Finally, one chart that has been making the rounds is the CDS (credit default insurance) on US debt. Striking trend, yes. But as Jim Bianco and Boaz Weinstein highlight, it’s a “tiny market” used primarily for “regulatory reasons”. In other words, don’t get too worked up about the chart - it’s not very revealing.

Economy

Why goods spending isn’t falling ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/47002aa9-18b3-4db4-ba34-3bac45d82268

In a note to clients published on Sunday, Spencer Hill of Goldman Sachs argues that something has changed. “Sustainably stronger consumer finances” have created fresh spending power for people at the bottom of the income distribution. After adjusting for composition effects, Hill estimates that real wage levels for the bottom 50 per cent of earners were 6.2 per cent higher in the first quarter of this year than in 2019 — and 9.6 per cent higher than in 2017. That implies something like $150bn per year in additional spending power for the bottom half.

This matters for two reasons: lower-income consumers spend more of each extra dollar earned, and they spend more of each extra dollar earned on goods, specifically. So long as bottom-half consumers have money to spend, goods consumption should stay high.

While I continue to believe there are a lot of cross-currents that make it virtually impossible to capture economic activity clearly or succinctly, I am sympathetic to the argument that significant income gains amongst lower wage earners is having a noticeable impact on both activity and inflation. This is eminently sensible, after all, since lower earners tend to spend a greater portion of what they earn.

I suspect this is coming as a surprise to many because it is such a different dynamic than what has been experienced over the last twenty years. During most of that time, real wage growth was flat and people got ahead by having assets that inflated in value. If those tables are turning, and it appears they are, there will continue to be a “surprising” amount of goods inflation.

Energy

OPEC+ Output Cuts Fail to Ignite Oil Prices

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2023-04-25/opec-output-cuts-fail-to-ignite-oil-prices

The overriding concern right now is weakening refining margins - the difference between the cost of crude going into the plants and the value of the products coming out.

If they narrow too far, refiners will start to reduce throughput, cutting crude consumption. Analysts at Citigroup Inc. and Royal Bank of Canada warn that a collapse in Asian margins is weighing on market sentiment and that oil prices can’t bounce higher if product cracks remain depressed.

Weakening refining margins would be noteworthy enough by themselves, but are especially so coming in the wake of the surprise production cut by OPEC+. It appears as if demand is weak and that the weakness is concentrated in Asia. While it’s too early to infer too much from these data points, they could be important early warnings signs for where the global economy is headed.

Technology

Large, creative AI models will transform lives and labour markets ($)

First, the language of the query is converted from words, which neural networks cannot handle, into a representative set of numbers (see graphic). gpt-3, which powered an earlier version of Chatgpt, does this by splitting text into chunks of characters, called tokens, which commonly occur together. These tokens can be words, like “love” or “are”, affixes, like “dis” or “ised”, and punctuation, like “?”. gpt-3’s dictionary contains details of 50,257 tokens.

The abilities that emerge are not magic—they are all represented in some form within the llms’ training data (or the prompts they are given) but they do not become apparent until the llms cross a certain, very large, threshold in their size. At one size, an llm does not know how to write gender-inclusive sentences in German any better than if it was doing so at random. Make the model just a little bigger, however, and all of a sudden a new ability pops out. gpt-4 passed the American Uniform Bar Examination, designed to test the skills of lawyers before they become licensed, in the 90th percentile. The slightly smaller gpt-3.5 flunked it.

But there are good reasons, says Dr Bengio, to think that this growth cannot continue indefinitely. The inputs of llms—data, computing power, electricity, skilled labour—cost money. Training gpt-3, for example, used 1.3 gigawatt-hours of electricity (enough to power 121 homes in America for a year), and cost Openai an estimated $4.6m. gpt-4, which is a much larger model, will have cost disproportionately more (in the realm of $100m) to train. Since computing-power requirements scale up dramatically faster than the input data, training llms gets expensive faster than it gets better.

The “Science” section of the Economist has an overview of AI that I found helpful in many ways. One of those ways is learning how the models work. They start with a process that breaks natural language down by converting words to “tokens” - which neural networks can understand. Another process, called “attention”, weights each pair of tokens in order to “form connections”.

An interesting attribute of LLMs is that as they get bigger, certain abilities “emerge” from them - presumably as they establish ever-more useful connections. Offsetting this exciting potential, however, is the cost of building bigger models. As the Economist reports, “Since computing-power requirements scale up dramatically faster than the input data, training llms gets expensive faster than it gets better”.

The tradeoff between more capable models and exponentially increasing costs means there are real economic constraints for the development path of artificial intelligence. This may be a good thing. If there are rapidly diminishing returns on expanding AI’s capabilities, then there will be a premium for finding more focused applications that serve useful purposes. Now that wouldn’t be so bad, would it?

The Cliffs Notes paradox

https://seths.blog/2023/04/the-cliffs-notes-paradox/

If you were on a long train ride with the smartest person in the world, what would you ask her? And how long before you went back to scrolling on your phone?

The main point Seth makes here is that learning requires effort, and unfortunately, effort that many of us are unwilling to make. While ChatGPT and various AI tools offer enormous opportunities to facilitate learning, they also offer enormous opportunities to “cheat”. Just as with Cliff notes in the past, merely having access to quality summaries is not a sufficient condition for learning. Most people don’t take advantage of it.

In addition, learning takes time. When you read a book, the understanding “seeps in, the aha’s are found, not highlighted”. True enough. There just isn’t a substitute for that - at least not yet.

Inflation

Bob Elliott makes a good point about inflation. In regard to how much “sticky” inflation is getting discounted by the markets, he responds, “The short answer is, it’s not.” This has a lot of potential to roil markets as it becomes progressively harder to maintain the position that inflation will be soon be going away.

Gold

Beyond Bed and Bath ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/b45d7225-76e8-4dc5-a780-2f02869b49bd

Central bankers who manage trillions in foreign exchange reserves are loading up on gold as geopolitical tensions including the war in Ukraine force them to rethink their investment strategies.

An annual poll [by HSBC] of 83 central banks, which manage a combined $7tn in foreign exchange assets, found that more than two-thirds of respondents thought their peers would increase their gold holdings in 2023.

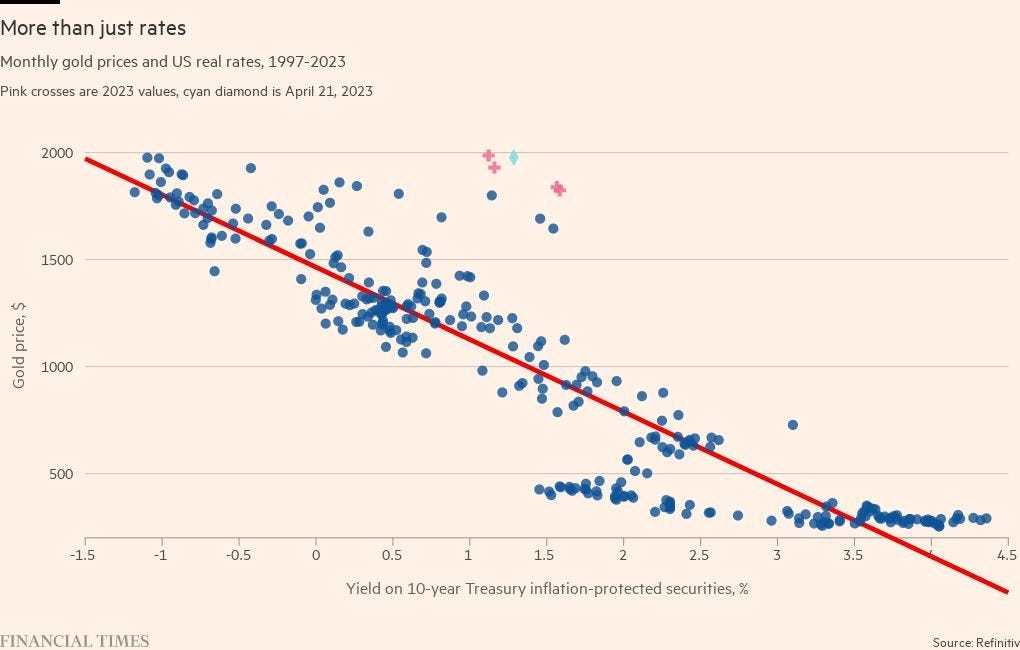

As can be seen in the graph above, there has been a longstanding relationship between gold and real rates (as indicated by the yield on 10-year TIPS). As can also be seen, recent experience has fallen noticeably outside the historical pattern.

One possible reason is the increased purchase of gold by central banks. Clearly this is an incremental change and on a scale large enough to matter.

My belief is there is something else going on as well. While the relationship with real rates makes sense (lower real rates make gold more attractive because there is lower opportunity cost of holding it), there is no particular reason why ten years is the right time horizon, nor is there a good reason to expect 10-year TIPS to perfectly reflect longer-term inflation expectations, and nor is there a good reason to believe longer-term inflation expectations adjust efficiently. Each of these items is even more true at turning points. As a result, it is better to think of the TIPS yield as a useful guide for gold rather than a concrete determining factor.

Further, in a world with too much money sloshing around, it has to go somewhere. As a result, my hypothesis is that a number of investors and traders are betting that longer-term inflation will pick up. In other words, current TIPS yields do not accurately reflect longer-term inflation. With lots of money available and stocks being expensive, buying gold is one of the better bets to be had. It may be early, but that money has to go somewhere.

Monetary policy

Fabricated Fairy Tales and Section 2A

https://www.hussmanfunds.com/comment/mc230424/

Take a close look at actual mandate – the “shall” – of Section 2A. The Federal Reserve “shall maintain the long run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy’s long run potential to increase production.” The Fed doesn’t have a “dual mandate.” It has a single mandate, which it is expected to pursue in a way that effectively promotes several policy goals: maximum employment, stable prices, moderate long-term interest rates, and financial stability.

Once the Fed expands its balance sheet beyond about 16% of GDP, which never occurred prior to 2010, interest rates are driven all the way to zero. Beyond that point, the Federal Reserve loses the ability to change the level of interest rates through changes in its balance sheet. Indeed, having expanded its balance sheet to the equivalent of 32% of nominal GDP, the Fed is presently operating monetary policy by explicitly paying 4.9% interest to banks on all of their reserves (even though the assets on its balance sheet were purchased at an average yield of only about 2.5%).

It’s just that people are constantly told fairy tales that make them imagine that systematic policy is not enough – aye, too boring when there be dragons to slay, beanstalks to climb, and kingdoms to save by valiant knights. These fairy tales encourage activist and even deranged policy experiments like quantitative easing, and obscure the fact that the Fed is violating its mandate. The children even come to believe that the Fed is an order of chivalry, with knights on white horses, when it’s actually the band of ogres that creates the problems in the first place.

Some gems here from John Hussman on the Fed and its monetary mission. One of the big points is the Fed’s mandate is really pretty simple - “to maintain the long run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy’s long run potential to increase production”. With the various Quantitative Easing (QE) programs, the Fed managed to push monetary and credit aggregates vastly out of alignment with economic potential.

This highlights a common challenge in the investment world. People often confuse “stocks”, in this sense the absolute quantity of something, with “flows”, the incremental change in that something. Day-to-day, flows are normally more important because they represent what changed in that short time frame. Stocks (or absolute quantities) are extremely important longer-term, but are occasionally forgotten amidst the flurry of short-term activity.

The stocks/flow issue often gets manifested in monetary matters in the form of cries about how rapidly M2 (a measure of money) is declining. Yes, M2 is declining rapidly (flows), and yes, in times past declining M2 was often a good sign of impending economic slowdown. However, the quantity of M2 (stocks) in relation to the size of the economy has never been so large either. As a result, the “declining M2” argument misses the fact that the total amount of money is completely out of whack. Samantha LaDuc depicts this nicely:

What really matters in regard to inflation right now is that the Fed reduce the monetary and credit aggregates to somewhere within the range of normalcy relative to the economy. All of the talk about M2 declining is a distraction and all the talk about rates is performative and effectively a “fairy tale”. While rates obviously do have an effect on parts of the economy, they are not the key driver of inflation. If you want to track inflation pressures, follow the Fed’s balance sheet.

De-dollarization

Robin Wigglesworth ($) at the FT reported on a recent research piece by Stephen Jen on the US dollar (USD). As with many of the same ilk, Jen opens with a sensational claim: “the US dollar has ‘suffered a stunning collapse’ as a reserve currency”. While this certainly grabs attention, the tone he concludes with is noticeably different - and milder: “If the US makes more policy errors and abandons the culture of self-examination, there will likely come a time when much of the rest of the world will actively avoid using the dollar.” True enough, but this isn’t much of a claim, is it?

I think a big part of what is going on with this story is that it touches on a number of topics that are emotionally evocative - and therefore that drive media engagement. Those topics include sentiments like patriotism, fairness, trust (or lack thereof) in US institutions, and political leanings. As a result, and as is so often the case, emotions get stoked and important issues get overlooked.

I discussed the issue of the capital account surplus of the US last week so I won’t repeat that here. Another issue that often comes up is the increasing efforts by many countries to replace USD transactions with their own currency. As George Magnus highlights in a rebuttal to Jen’s article, this is both understandable, and immaterial to the reserve currency argument.

Again, we can all acknowledge that there is a shift towards paying invoices in other currencies, and trying to set up alternative payments and clearing systems that bypass SWIFT and the TIC system.

Use of Chinese currency to settle more bills, though, does not advance the cause of the yuan as a reserve currency, let alone an alternative to the US dollar. Recipients of yuan are still left with the issue of either keeping a currency asset that is still barely used globally, or selling it for readily tradable currencies with open and transparent financial architectures.

So, one point is that much of the de-dollarization argument seems to conflate the migration to greater local currency settlement with an intractable balance of payments problem. They are different issues.

Another point is the debate is attracting a lot of “macro tourists”, and I have to admit I am one. A number of these tourists, however, are venturing off on their own and passing off sensational stories as “analysis”. A more sensible approach is to find a good tour guide. On that front, Michael Pettis, Brad Setser, and George Magnus are all exceptional in my opinion.

Implications

As the x-date for the debt ceiling nears, so too does the prospect of massive issuance of debt very shortly thereafter. This will force a great deal of selling of financial assets in order to absorb all of the new debt. If banks and other institutions are being forced to sell assets at the same time, which looks like a reasonable expectation, the supply of financial assets for sale could significantly exceed the demand.

Predicting such an event is a fool’s game for lots of reasons, but the conditions are certainly setting up for some pretty rough market action this summer. The main points for long-term investors to remember is when such disruptions happen, correlations go to “1” - meaning everything sells off. There are no safe havens (except cash).

The implication for long-term investors, then, is to incorporate the possibility of a severe selloff. Partly this means maintaining a relatively defensive position. Partly it means placing a higher hurdle on acquiring risk assets. Finally, it means preparing to pounce on attractive assets if they become unduly cheap.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.