Observations by David Robertson, 4/7/23

I’ll be taking a break next week from Observations, but be on the lookout for a new Market Overview for the first quarter. Observations will return on the 21st.

In the meantime, enjoy the spring weather and have a Happy Easter!

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

If it feels like stocks have gone up and gone down, but haven’t really done anything, you’re right! As Tier1Alpha reports, the “‘consolidation’ moniker has been well-earned”. The S&P 500 is closing in on the third longest streak since 1928 of hovering between the 100-week and 200-week moving averages. The lack of an identifiable trend while higher rates are doing their damage lends credence to the hypothesis of a “controlled” demolition.

That said, the S&P 500 produced a healthy 7+% return for the first quarter. The attribution analysis is easy. As @SoberLook illustrates, the vast majority of it came from seven stocks:

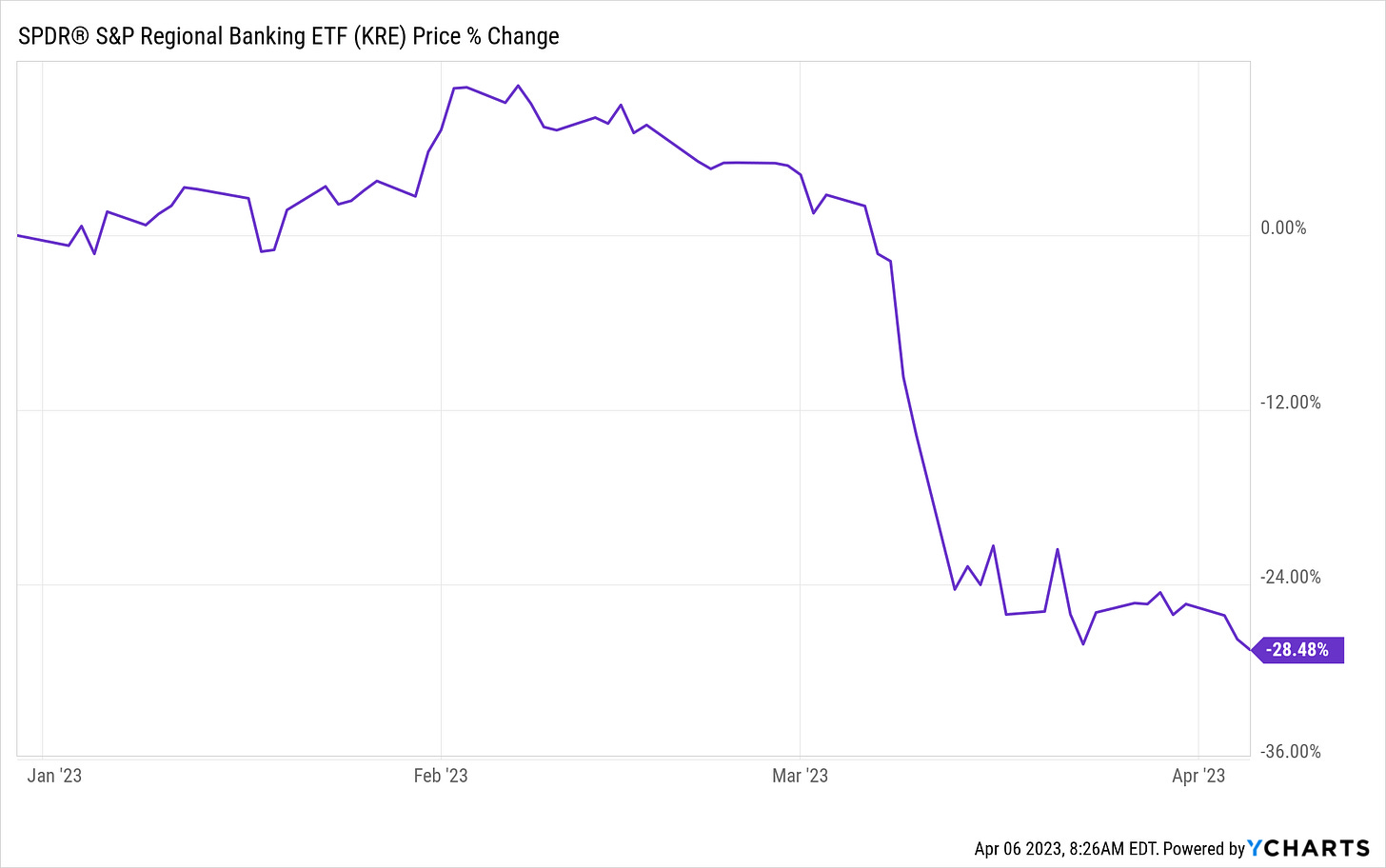

In stark contrast to the large tech stocks, banks had a terrible quarter. Not only were they hit hard by the SIVB and SBNY failures, but they never regained any ground after the Fed and Treasury came in to settle things down. One observation is with the stocks continuing to hit new lows there appears to be an expectation things will get worse. Another observation is when banks are sucking wind the market usually follows.

On a different note, the graph below certainly elicits some sentiments, not least of which is, “kids these days!” While the sample size isn’t huge, the story the graphs tell comports with my own experience and I suspect that of many others as well. The values of patriotism, religion, having children, and community involvement all show steep declines between 1998 and 2023. Only money shows a noticeable increase.

While it is probably easy for a lot of older adults to believe the graph is proof that the moral character of younger adults has deteriorated, it is important too to consider circumstances in addition to character.

On that note, human nature doesn’t really change over time - but circumstances do. With exceptionally low interest rates most of the last fifteen years, and with policies that favored capital over labor, it has been exceedingly difficult for young adults to get ahead or to realize a similar lifestyle to their forebears. It’s no wonder money has taken a more prominent position.

As a result, I read the graphs as an indictment of societal choices, not the moral decay of a generation. Give people a fair chance to make a living and there will also be interest in community and the chance to raise a family. Reduce the opportunities and add a bunch of debt right out of the gate and other interests suffer. People must prioritize. Therefore, I tend to interpret the changes in values as the outcome of necessity borne from a dearth of economic opportunity.

Economy

ALLY is a big car finance company - it came out of GMAC after the financial crisis in 2010. So, it’s capital is falling rapidly while delinquencies on auto loans are surging. This is a good illustration of what is happening in the financial economy - everywhere. Just as borrowing costs are going up, so too are credit costs going up. Ugly, and about to get a lot uglier.

This is also a good example of how to view the economy as a whole. On one hand, the financial economy is going to be a constant fire fighting brigade for the foreseeable future. There is no easy way out.

On the other hand, the consumer economy is holding up relatively well. There will be ripple effects for sure - tighter lending standards will impede consumer spending and unemployment will rise, but mostly these two different parts of the economy will be on different trajectories.

Oil

OPEC+ made an announcement of production cuts last weekend that surprised everybody. Rory Johnston ($) described some possible reasons: “a preemptive adjustment ahead of slower than expected demand growth, a retaliation against the White House for failing to refill the SPR as committed, and as punishment for what many members saw as unjustified short-pressure following the mini-banking panic”.

Michael Kao agreed a possible reason for the cut is “OPEC+ is seeing something nasty brewing from a demand standpoint and wanted to get ahead of it”. He framed the “retaliation/punishment” hypothesis as more of a personal vendetta between Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) and President Biden, however. When I followed up with him in the comment section of his Substack post, he agreed any kind of retaliation the cuts might reflect would be directed just as much at China as at the US.

To me this is a nontrivial distinction. While personal acrimony certainly can drive the behavior of global leaders, decisions like the OPEC+ cut are immensely complicated and rarely revolve around a single variable. Although the MbS-Biden relationship provides a juicy narrative, inordinate attention on that aspect of the story overlooks the important implications for the Saudi-China relationship.

Finally, although a short-term boost in oil prices was warranted, it is too early to judge the longer-term effects. For one, OPEC+ members are notoriously inconsistent with compliance to agreed changes. For another, if it is a pre-emptive cut, we will have to see how much demand actual does fall off. If global demand is falling off and significant spare capacity re-emerges, however, the medium-term view on oil will be less positive.

Moral hazard

Shortly after bank problems emerged in the first quarter came public policy responses. Shortly after that came outrage over the moral hazard involved in those policies.

With Silicon Valley Bank, just ten entities had a total of $13B in uninsured deposits that were saved. With Credit Suisse, holders of AT1 capital were wiped out even though junior equity holders were not. The pattern compelled Ed Luce at the FT to characterize the financial system as a place “where the risks of moral hazard now seem to be totally ignored”.

While I hate moral hazard and believe it is a hugely underappreciated risk, I also think Luce overstates the case. First, when there is a bank run, that run needs to be stopped. Period. There are better and worse ways to do that, granted, but the greater good needs to be the priority. Situations like this are not the time to quibble about perfection.

Second, the reason why perfection is an unreasonable goal for public policy is because there are always vested interests acting against it. That’s just the way it is. I don’t like it either, but it is a reality. The challenge is even greater in countries where inequality is more extreme.

Finally, I strongly suspect a great deal of moral hazard potential will be eradicated by higher inflation. Moral hazard was an especially pernicious problem when low inflation and interest rates created an environment largely bereft of consequences. Indeed, the worst offenders not only lived to tell about it, but absolutely thrived in the process.

Higher inflation - means higher rates - means next time around, mistakes will be costly. Even if people act recklessly and get by with it now, it is very unlikely they will be able to do so next time. Further, they absolutely will not be able to make a business model out of such recklessness in a world of higher rates and lower liquidity.

In conclusion, I think the recent outburst of attention on moral hazard is overdone. While it will create meaningful constraints on public policy in the future (i.e., there will be little tolerance of bailouts), the emergence of real consequences themselves is likely to do more to quell moral hazard than anything else.

De-dollarization

One of the narratives that has gained steam over the last few weeks has been that of de-dollarization. This is the argument that the US dollar (USD) is losing its status as the global reserve currency.

There are valid reasons to hear the idea out. High and rising trade deficits signal undue dependence on foreign goods. High and rising debt and deficits inspire little confidence in the country’s fiscal resolve. Further, competing countries like China are growing weary of USD’s “exorbitant privilege” and would like nothing better than to undermine its annoying prominence in global trade.

Each of these reasons, however, fails to stand up to closer scrutiny. Persistent trade deficits, properly diagnosed (according to Michael Pettis and Matt Klein in Trade Wars), are a function of USD’s reserve status and the decision by countries like China and Germany to run export-driven economies. It’s not that the US overspends and other countries have to produce the goods. It’s that when the world ex-US is a net exporter, the US (due to its global reserve currency status) is left to sweep up the excess. Proponents of de-dollarization get the causation reversed.

High and rising debts and deficits are largely a function of this trade imbalance. If there is surplus production, it has to end up somewhere and that somewhere is the US. This happens even if the US can’t afford to pay for it. As a result, deficits go up.

As much as a country like China may want to displace USD, wanting and accomplishing are different things. For one, having a large and liquid Treasury market and a freely floating currency entails a willingness to abstain from control. This openness makes the currency attractive to others. China is wholly unwilling to cede control of its currency or of financial markets.

Finally, reserve currency status is essentially a projection of national power as Michael Kao argues in a recent paper. Such power is manifested in two ways. One is strength through assets like natural resources and favorable geography. Another is through military strength which can be projected around the world. De-dollarization fans focus on cash flows but overlook assets.

For all these reasons, it is curious why de-dollarization is such a hot topic right now. As Brent Donnelly points out, this topic heats up every few years. As Ben Hunt describes, it sure seems like external forces are at play this time around - trying to sow discord in the country. Regardless, the fact even barbers are now talking about the collapse of the dollar suggests we may be reaching peak hype.

While it is useful to address the arguments as to why USD may be losing its status, it is also useful to consider the issue from the opposite perspective. Yes, having the reserve currency entails certain privileges, but it also entails certain obligations. When those obligations become more onerous and the privileges become less advantageous, there is an argument to be made for changing the arrangement.

I think this is exactly what is happening. The clearest way for the US trade deficit to come down is for net exporting countries like China and Germany to re-orient their economies to produce greater internal demand - and therefore export less. That wasn’t being done voluntarily so it must be done forcefully.

What the de-dollarization hysteria seems to overlook is the possibility that the US recognizes the unsustainability of its debts and deficits, recognizes nobody else is going to resolve the underlying imbalances, and therefore must act on its own. These are good things. How would it be better if the US simply resigned itself to persistently unsustainable deficits?

Investment landscape I

Easy, right? If your stress test reveals your company could blow up, then just change the assumptions. Brilliant! Smithers, who is that young go-getter?

It turns out, the insanely reckless and destructive kind of management behavior we used to make fun of became … standard protocol. Of course it took a while to fully evolve, but it did.

I wrote a piece about the changing norms in the technology space about four and half years ago. I reported, “many management teams are essentially tasked with the effort of inflating expectations,” and “Risk is now considered a feature, not a bug."

Further, views towards accounting changed long ago and it is no longer considered “a value-added function." One CFO, according to an HBR article, noted "that the CPA certification is considered a disqualification for a top finance position [in their company]."

In short, the business landscape is littered with managers who long ago abandoned the concepts of using data for better decision making and using common processes and common sense to manage risk. This is not a matter of a bad apple here or there, but rather one of systemic scope. As a result, there will be a lot more companies that fail. In hindsight the reasons will seem silly.

Investment landscape II

Day to day and trade by trade, the price of a stock is set by its supply and demand. This has become an even more prominent subject as passive investing has come to dominate stock flows. In other words, as money comes in from target date funds and other popular retirement options, there is a constant demand for stocks regardless of price. Since supply doesn’t change much in the short-term, this tends to put upward pressure on stocks.

This dynamic looks to be primed for change. With baby boomers owning a large share of stocks, and facing minimum required distributions from IRAs and a desire for less volatility as they continue to age, they are likely to start selling down some of their holdings. Naturally, this will increase supply of stocks to be traded.

If the incremental sales merely match the new inflows from automatically invested retirement funds, prices may not change very much. However, if the incremental sales overtake the inflows, the pricing dynamic would change significantly. At that point, the marginal buyer of stocks may not be very interested in stocks at all, in which case prices would have to be much lower for a trade to occur.

Demographics has long been a driver of risk assets but over very long periods of time. The coming transition is apt to be a lot more noticeable.

Implications

In the midst of a lot of turmoil in the quarter one of the common themes was hysteria. Whether it was the overreaction to the bank problems, the explosion in headlines about de-dollarization, or most recently, the Trump indictment, the quarter was characterized by stories that spun wildly out of control.

This begs the questions, “Why?” and “Why now?” The most obvious answer, to me at least, is to provide a distraction from the darkening economic clouds. As the financial economy is being slowly but persistently asphyxiated by higher rates, the consumer economy is clicking along at a strong enough rate to keep inflation in play. As a result, the Fed has very limited ability to ease monetary policy.

Some time in the not-too-distant future, the financial economy is really going to start seizing up. The drip-drops of individual company failures will turn in to a pitter patter and then become a downpour. As that happens, it will be best for policymakers if people don’t notice so much - because they are engrossed in other events.

Finally, the following outlook by Sam Lawhon is apropos:

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.