Observations by David Robertson, 5/16/25

It looks like budget talks are starting to grab headlines from tariffs. At least it’s something different. Let’s dig in and figure out what’s going on.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

The week started off with great guns a blazin’ as stocks jumped out of the gate on Monday with a 3% gain. Gold was slammed as was volatility. Once the big move was in place from overnight futures picking up on trade talks with China, however, there was little action during trading hours.

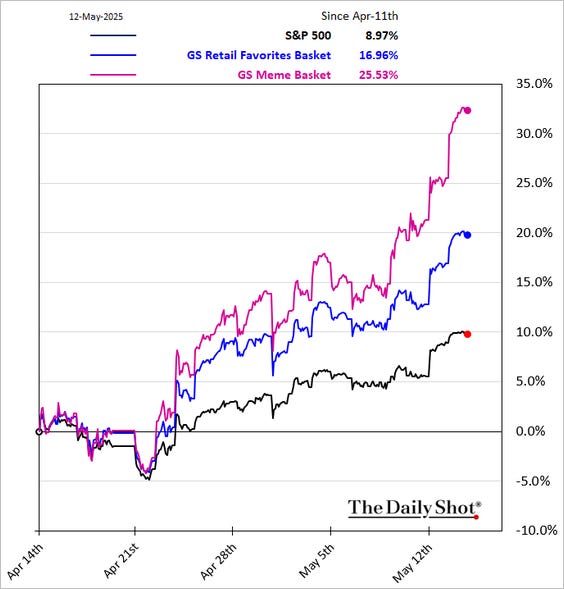

A couple of graphs from The Daily Shot illustrate the key drivers of the rally. One factor was short covering:

Another factor was meme stocks:

Clearly, flows and animal spirits are powerful forces — and forces that don’t care about underlying fundamentals.

While there are are still a lot of signs of distress among consumers, one of the most notable changes recently has been the expiration of student loan forbearance. As Ben Hunt shows, a new chunk of delinquent student loans makes a bad consumer credit picture look that much worse:

Finally, an interesting observation from John Authers ($) at Bloomberg. Apparently, the person who represents the Trump administration on news updates matters quite a bit to the market:

Politics and public policy I

I Don’t Care If MAGA Burns Down Your House ($)

https://www.thebulwark.com/i-dont-care-if-maga-burns-down-your

Let’s start with Emmitsburg [MD]. The town is home to the National Fire Academy, which is like the Army War College for firefighters. The NFA became a target of DOGE and, by order of the Trump administration, is no longer conducting in-person classes. This development is bad for the local economy, bad for the institution of the National Fire Academy, bad for firefighters, and ultimately bad for anyone, anywhere, who might someday need emergency services.

The general view of the Emmitsburg Trump voters NPR spoke with was:

They like Trump.

They want Trump to shut down a bunch of government programs.

They do not have any specific recommendations for programs they believe are wasteful.

However they are certain that their pet program is valuable.

And so if Trump restores funding to the National Fire Academy, they will continue to support him.

But if Trump does not restore funding to the NFA, then—and only then—they will conclude that his assault on government is harmful.

I find this piece to be especially troubling because it touches on a couple of the more malignant phenomena in this political environment.

First, it highlights an extremely high level of insensitivity to others. People seem to have virtually no concern or curiosity about the negative effects of shutdowns and job losses on others. Rather, there is just a general belief that a bunch of programs should be shut down.

Second, there is a strong belief that the program(s) that affect these people directly are important. This is extreme selfishness. What’s good for me is good; everything else is bad.

None of this is to say the high level of insensitivity is isolated to Trump supporters. I don’t think we’d be where we are today without a pattern of neoliberal policies that exchanged cheap goods for manufacturing jobs and decent working wages. Nope, that was grossly insensitive too. Nonetheless, in both cases, people have gotten acclimated to a steady state of insensitivity and selfishness.

This widespread mindset of insensitivity to others combined with extreme self-interest bodes poorly for both politics and economics. In politics, it makes it virtually impossible to establish any kind of quorum on policy. Any time one constituency benefits more or less than another, there is fighting. I agree with Jonathan Last’s summary that “This is a myopic, untenable civic approach to democracy.” I would add, though, it’s been going on for a long time.

As a result of this atomization of the electorate, it’s unlikely the political process can arrive at solutions to big problems. That means core problems will continue to get worse, voter discontent will continue to grow between and within political parties, and economic growth will suffer due to growing uncertainty and failure to adequately address persistently high fiscal deficits. So, things stand to get a lot worse before they get better.

Politics and public policy II

As Treasury funds continue to deplete under the debt ceiling, the deadline is rapidly approaching for a new budget bill. The outcome will be extremely important because it will dictate the degrees of freedom the Trump administration has to pursue its agenda. A nice summary of the situation was provided in the latest Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee report:

While most attention has centered on trade policy, Treasury investors are also monitoring fiscal developments. With a compromise budget resolution passed by the House and Senate, interest rate markets will be sensitive to deficit implications of the details of the fiscal package and look forward to debt limit resolution. Assumptions about future tariff revenue also affect projections for future deficits and Treasury supply. Market participants are questioning a credible path to a more balanced deficit outlook over the medium term, contributing to the rise in term premium.

This is really where the rubber hits the road for the Trump administration: Will it be able to secure the wide-ranging tax cuts it wants, and the increases in defense spending, without blowing out deficits?

So far, it looks like that will be exceptionally hard to do. Nonetheless, the tradeoffs that are accepted will be instructive. So too will be the process getting there.

For one, while the Trump administration has worked hard to present a united front, the actual process of legislation is revealing a great deal of disharmony in the Republican camp. This isn’t unusual, but it does highlight the divisions that exist.

For another, the budget process is also at least implicitly highlighting early failures of the administration. If DOGE had been able to eliminate a fraction of the fraud and waste it targeted government expenses would be much lower. They aren’t. If huge tariffs were successful they would be bringing in large volumes of incremental revenue. That didn’t happen either. As a result, the basic budget proposition is a lot more spending, on top of already huge deficits, with virtually no offsetting benefits. Yay!

This raises an interesting question: Are the Trump administration’s reversals on DOGE and tariffs indicative of changes in policy direction? Or were they just improvisations? In other words, are they part of a cohesive plan, intimately tied to and calibrated with tax cuts? Or are they one-offs that just reflect the administration’s next best idea for the moment?

This begs an even more important question: Is the Trump administration really about reform or not? Adversity tends to reveal character and as the budget process continues, the entire world is learning more about the Trump administration. We are likely to learn quite a bit more about its intentions and ability to improve economic conditions.

Investment landscape I

Even more noteworthy than the runup in stocks over the last few weeks has been the runup in bond yields globally. As Russell Clark ($) notes in a recent Substack, “JGB yields are pointing to broad based bond weakness. During all the volatility 30 year JGB yields rose to new highs. This is a sharp break with the last 20 years of so.”

Indeed, US Treasury bond yields have also been going up. Don’t look now, but as of Tuesday, the 10-year yield was just a hair under 4.5% and the 30-year yield was 4.94%. As a reminder, these are right at the thresholds that triggered the pause of tariffs from “liberation day” which were also known as the “Trump put”.

Inflation really hasn’t been the issue; it has remained fairly moderate. Instead, the rising yields look like the market’s commentary on government policy. For example, Clark observes:

the Trump presidency has bulldozed through all concepts of conflict of interest and allowed a businessman to both gut the IRS, and compromise the data collection. In emerging markets, this is called “state capture”

What this “state capture/liberation from big government” means in practice is that US treasuries are not really worth anything. Like an emerging market, the issue is when the market recognises the collapsing creditworthiness of US treasuries.

In essence, the bond vigilantes appear to be doing their job. They are recognizing the rapidly eroding creditworthiness of the United States and are demanding premiums in the form of higher yields.

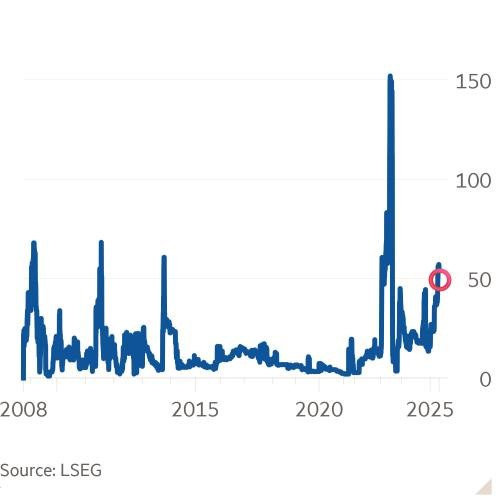

This can also be seen in the form of rising credit default swaps (CDS). As Robert Armstrong ($) points out, “Credit default swaps on Treasuries, a direct hedge against the possibility of a US sovereign default, are the most responsive to the US’s budget situation. The cost of a 1-year credit default swap on a Treasury rose substantially in 2011, 2013 and 2023:”

Another important signpost that concerns are increasing about Treasuries is the push for regulators to reduce capital requirements for banks by reducing the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR). While the headline purpose is to ease regulation, the reason why this is being done now is to increase demand for Treasuries by increasing the incentive for banks to own them.

This raises two interesting questions. One, Scott Bessent highlighted a reasonably low yield on 10-year bonds as a key performance indicator of his economic plan. By that measure, he is on thin ice again, regardless of what stocks are doing.

Another question is the competition between narratives for stocks and those for bonds. When the bond narrative was front and center, the narrative for stocks got trashed. When the narrative for stocks got rejuvenated, the narrative for bonds got trashed.

Is it part of the plan to toggle back and forth between the two? Does the competition between stock and bond narratives indicate how little space there is for policy to thread the needle? Is this whole exercise just buying time in order to soften the economic slowdown?

Any or all of these things could be possible. One thing is certain though: Higher yields will make it easier to lure in bond buyers in order to absorb the coming increase in Treasury issuance. They will also put additional pressure on growth though.

Investment landscape II

Neil Howe’s work (along with William Strauss), The Fourth Turning, has provided such an interesting framework to understand what is happening politically, economically, and socially, because so much of it has been right. As we have been proceeding step by step through this recurring historical pattern, Grant Williams asked ($) in a recent interview what is left for us to experience in this Fourth Turning?

Neil responded:

Obviously the catalyst is long behind us and regeneracy, we’ve seen the regeneracy. We may have seen yet another regeneracy with Trump 2.0 going off in a somewhat different direction. Typically, there’s more than one regeneracy. What we haven’t seen is the decisive moment when the struggle is joined.

This presents an interesting thought experiment: What would it take for the struggle to be joined today? Neil himself asks, “what is America today?” suggesting there is no clear unifying idea. The FT ($) describes “Young Americans’ confidence in the apparatus of government has dropped dramatically to one of the lowest levels in any prosperous country.”

Ben Hunt ($) provides an even more expansive view:

I think the office of the President of the United States — the personification of the idea that there is a shared meaning in being an American — is now dead.

But no. The rot of I-got-mine-Jack is too strong, too far gone throughout ALL of our political institutions and ALL of our political ‘leaders’. I am now certain that there is zero hope for the unifying idea of America that I grew up with. And I feel like a fool for ever believing that there was.

War is often the impetus to galvanize a population to join the struggle, but given this state of affairs and the Trump administration’s disinclination for protracted conflict, external conflict doesn’t seem very likely, at least not now. By the same token, internal conflict also seems like a longshot.

What else might do it? In my opinion, one of the fundamental flaws of Trump as a leader is his compulsion to constantly craft a flattering narrative. This tendency is inherently divisive. You either believe the stories that often contradict facts and reason or you are forced to conclude that many of his actions and policies are harmful to the American people.

As a result, the way these two different views might converge is a moment when Common Knowledge emerges that Trump is bad for the country. This could happen in one of two ways.

One would be a Richard Nixon moment. Trump does something so ludicrous, so outrageously harmful, that even his own party will not support him. Impeachment proceedings ensue and he resigns. This by itself may not change many things, but it would be a start.

Another possibility would be a situation in which it becomes Common Knowledge that Trump is unfit for office. Imagine a moment like Biden’s debate performance with Trump where everyone can see that everyone can see this person isn’t fit. Something that breaks the belief system that Trump is a powerful and effective leader. Something that makes abundantly clear that we are stronger when we work together.

The main point is none of these scenarios seem imminent at the moment. As a result, the Fourth Turning will continue to grind along until there is some better pretense for widespread cooperation.

Investment landscape III

Last week I discussed the perspectives of macroeconomics and geopolitics and the importance of understanding the ways in which they influence one another. This week podcasts by Grant Williams with Russell Napier ($) and Neil Howe ($) add more perspective to the discussion.

From Russell Napier:

We won’t look back and say, Trump caused any of this. We’ll say that other things caused Trump. So in some ways the other things are driving policy, it’s not policy driving these other things. And one of the mistakes I think we can make as investors is to assume that the politicians are making the decisions rather than being driven to those decisions by circumstances.

Nobody in our industry is in any way qualified for any of this … they didn’t teach any of this stuff in business school and they didn’t teach it on the syllabus. So it’s a good point not to turn me into a geopolitical analyst because I’m not, but I am a historian. And historians maybe have something to say about this even if that’s not... It may not be as good as a geopolitician, but it’s certainly better than MBA, let’s put it that way. So I’m afraid that I think the industry is unqualified for this, which is why there’s a scramble on now for expertise.

And from Neil Howe:

That leaders come into where they are because they have no real other option. They always move to the void. They always move to where they are beckoned to go. I think Trump is in this position today, not because he maliciously pushed America into it, but because America is ready for him. I really do. I think America was wanting a guy like Trump, for better or for worse.

It’s interesting both of these historian’s have a similar view that politicians don’t make history so much as fill a void created by economic, social, political, and geopolitical conditions. This suggests it is far more important to understand the underlying conditions than the people. This is what Napier means when he says, “one of the mistakes I think we can make as investors is to assume that the politicians are making the decisions rather than being driven to those decisions by circumstances.”

It’s also interesting that Napier highlights the same shortcoming Clark does in that there is precious little political expertise in the investment industry. Napier goes further: “Nobody in our industry is in any way qualified for any of this … they didn’t teach any of this stuff in business school”. This observation is a good reason to be suspicious of most industry research and a good reason to be more cautious than usual in regard to taking risk.

Implications

In the short-term, it’s just hard to tell what the Trump administration wants. Does it want a “controlled demolition” of stocks as seemed evident a month ago? Or does it want a booming stock market as seemed apparent from the tariff discussions with the UK and China? Or will the administration pursue a back-and-forth approach to buy time? Regardless, traders will be left following a very unpredictable pathway.

Longer-term, the direction is much clearer — because unsustainably high fiscal deficits (i.e., circumstances) place substantial constraints on public policy. Either policy will act within those constraints and cause growth to slow down or it won’t act within those constraints and long-term bond yields will blow out and slow down growth on their own. Either way, we get to the same place. Ultimately, we end up with lower growth, higher inflation, and suppressed bond yields.

Interestingly, as Napier also highlights, “preserving wealth now is not about intelligence, it’s about courage”. Namely, it’s about making portfolio allocations that are very different from standard 60/40 (stock/bond) weightings. Also interesting is the reality this type of nonconsensus positioning will be easier for individuals than for “professionals” who worry about career risk.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.