Observations by David Robertson, 5/17/24

All eyes were on the consumer price index (CPI) this week. It turns out everyone likes a story, even the market.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

Market participants started the week off waiting with bated breath for inflation numbers later in the week. It was against that serene landscape that the re-emergence of Roaring Kitty and the retail frenzy for stocks like GME and AMC made such a splash. Both stocks were up over 70% on Monday and up big again on Tuesday.

Regardless of the message the Fed thinks it is sending, the message received by retail investors is it is open season for speculation. Apparently, the words, “sufficiently restrictive,” do not mean the same thing to retail investors as they do to the Fed.

On a separate note, earnings for the first quarter have been fairly good overall. As Bob Elliott highlights, however, expectations for the rest of the year appear “quite elevated” as “Q4 y/y earnings growth is expect to be 17% at this point”. It’s hard to reconcile the expectation of rapid earnings growth AND Fed rate cuts.

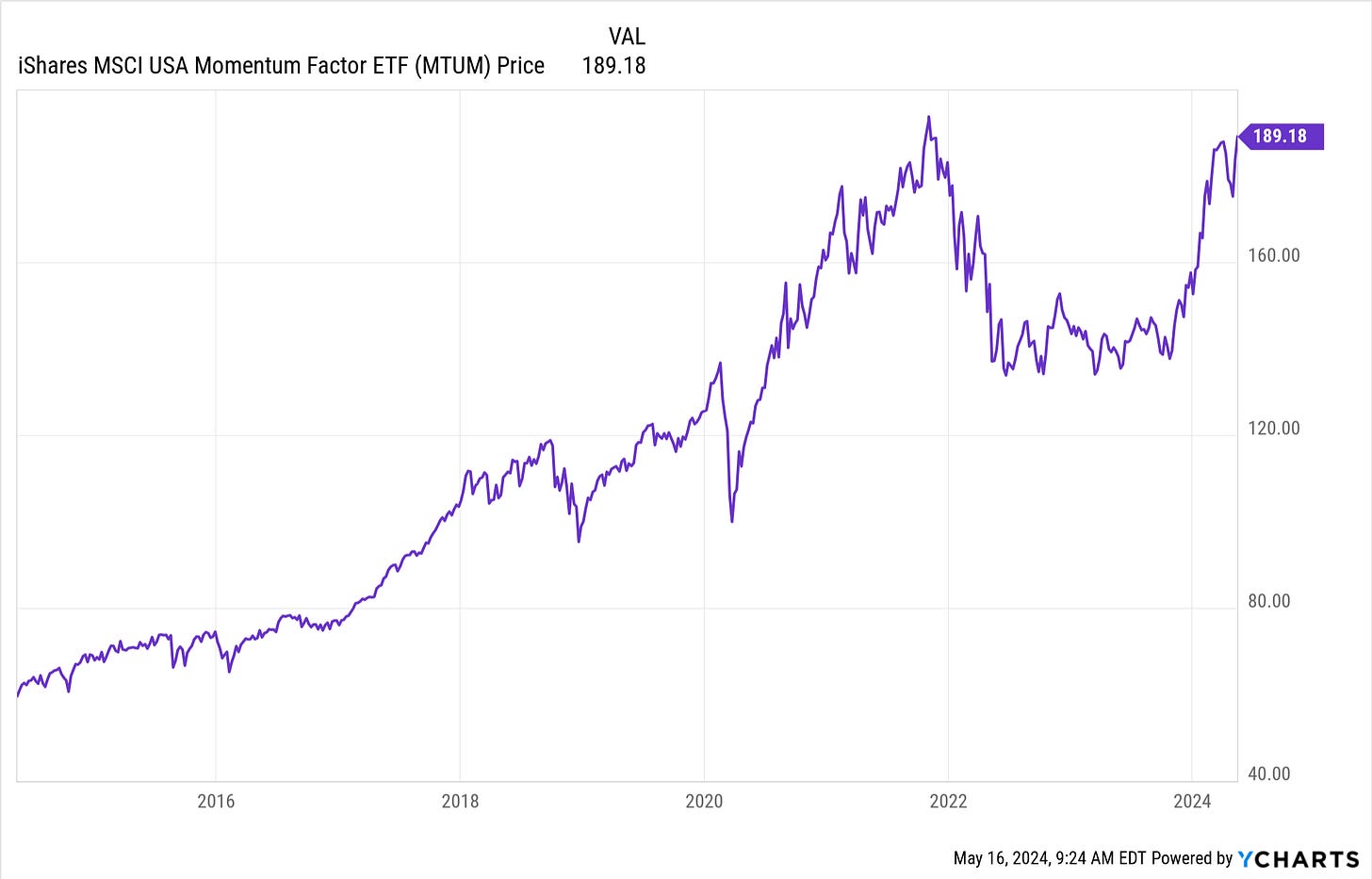

One thing that has been making a resurgence lately is momentum. The momentum ETF, MTUM, came within spitting distance of a new high for the year on Wednesday and is right at the levels of the top set back in the whacky days of fall 2021.

Are we off to the races again or is this a double top? I have my thoughts … and so does Bill Gross: “Should investing be as easy as sitting on your butt and watching screens? Momentum has limits.”

Economy

A debt crisis at the economy’s edge ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/8b935a91-725a-4c3b-b03a-962ab6bc37f8

Americans, in aggregate, do not have a debt problem (except of course for the debt carried by their government). But aggregation deceives. As we have discussed in this space before, households who are on the lower end of the income spectrum and carry floating rate debt appear to be in real trouble. This is showing up in both delinquency statistics and the earnings of companies that serve the working class and poor.

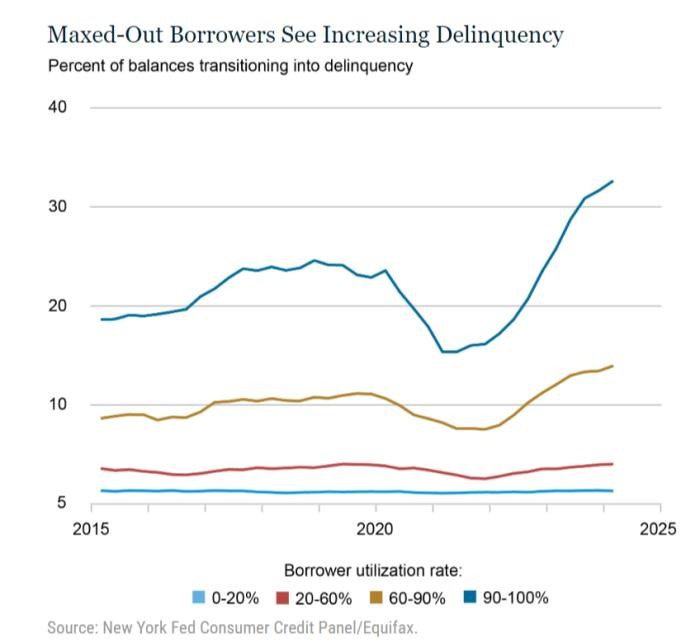

New York Fed economists, in a blog post accompanying the report [the New York Fed’s household debt and credit report], looked at delinquency rates stratified by borrowers’ credit utilisation. They found another striking trend: borrowers who have “maxed out” their credit limits are going delinquent at a rate unseen in the last decade. Again, these are typically younger and lower-income borrowers. Their chart:

This is a nice analysis by Robert Armstrong of the FT that helps reconcile the very mixed signals we keep getting on the economy and consumer health. In short, consumers who rely heavily on debt are getting pushed to the brink. Others are mostly doing fine. As Armstrong concludes, “Strong household balance sheets on average — but acute stress at the margin.”

Of course, it may be the Fed’s analysis understates the problem. Michael Pettis posts, “Household debt in the US may be much higher than the data suggest because of ‘Buy Now Pay Later’ platforms that refuse to disclose their credit numbers.” Fair point.

This makes the Fed decision on rate cuts that much more interesting. On inflation and economic data alone, there really is not a strong case to cut rates, at least not in the near future. However, with “acute stress at the margin” affecting mainly younger consumers who skew Democratic, rate relief could become intensely political. This could be a major force behind the market’s expectation of rate cuts.

Inflation

On Tuesday morning, the producer price index (PPI) came out and the number for April was 0.5% which was much higher than expected. Underneath, factors contributing to the Fed’s preferred measure of personal consumption expenditures (PCE) were relatively soft and prior numbers were revised down. As a result, the market took the report in stride.

Wednesday, the much-anticipated consumer price index (CPI) came out and came in pretty much in line with expectations. While there were no big, ugly upside surprises, there also weren’t any significant accounts of falling inflation that might lead to the Fed cutting rates.

Bob Elliott summed the CPI report up well:

Every single one of these numbers is inconsistent with the Fed's inflation mandate and they all have printed worse since JP [Fed Chair Jerome Powell] signaled a coming pivot to easing.

Nonetheless, futures popped half a percent after the report and stocks finished the day up over 1%. It was an unusually bullish response to an unusually mundane report, but that says something about the market here.

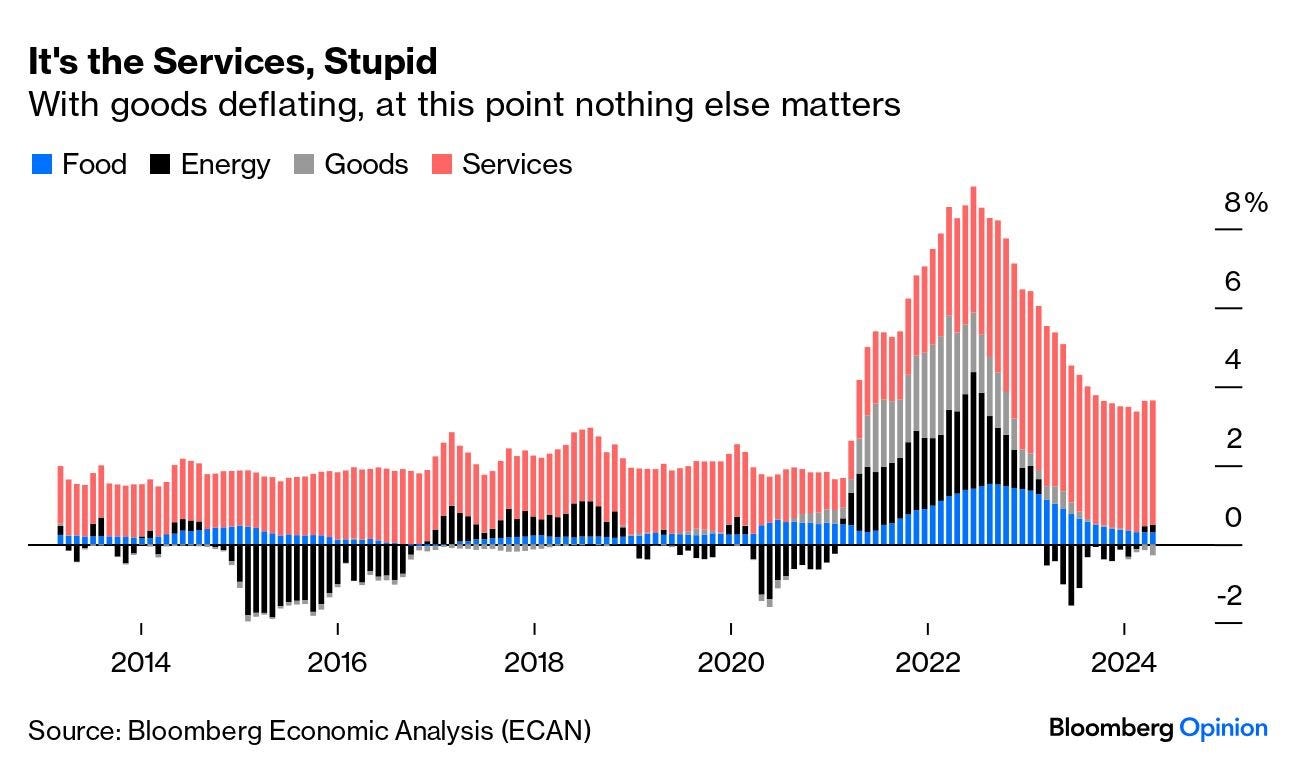

John Authers also added perspective with this useful graphic:

Most of the attention is being placed on services which is not only the largest component of CPI, but also the one most stubbornly remaining above target. While there is a great deal of debate about where the services component is going, the other components should not be taken for granted. With PPI posting on the high side this week and select commodities (e.g., copper) shooting higher, there is undoubtedly upside risk to food, energy, and goods.

Monetary policy

Interesting post from Craig Shapiro:

If Japan can buy oil in yen, they will be able to tolerate a much weaker JPY because it won't lead to the imported inflation that they are so concerned about. Since they have open capital account and can't raise rates because of too much debt, weaker yen is the only option.

Saudi will take yen and they will buy Japan goods and services with it, invest excesses in Japanese FDI, property, and stocks. MBS is going on a shopping spree. Any leftover trade balances can be settled in gold.

US blessed this because it is now in our strategic interest to allow others to buy oil in local currency so they don't have to sell USTs to raise US$ to buy more expensive oil. Janet has too many USTs to sell and wants to slow down others selling too.

I am beginning to think X and Substack are conspiracy propagation platforms as much as anything. They give everyone (including me!) a voice to express whatever cockamamie theory they may have about something.

That said, as Dave Collum repeatedly highlights in his year-end reviews, “powerful people conspire”. Further, what’s the difference between a conspiracy theory and a hypothesis that happens to explain unusual phenomena very neatly?

In leaning towards the latter definition, Craig Shapiro makes the case that some back room agreements help explain Japan’s tolerance of yen weakness and the US interest in forestalling additional pressure on longer-term Treasury yields. If true, this would amount to back door yield curve control which in turn would signal a playbook for monetary debasement. I suspect there is a good chance it is.

Shapiro’s follow up comment is also relevant here: “It just buys time for either a productivity miracle to come (unlikely) or for the US to regulate banks to own more USTs”. Yes. Sometimes policy is more about living to fight another day. Again, if true, Treasury knows it has a problem and is desperately trying to shore things up.

Public policy

One of the mistakes I have made in the past, and a tendency I continue fight in myself, is to ascribe too much importance to “sound economic theory” in evaluating public policy options. Yes, economic theory can provide some insights into costs and benefits of various policies, but it can miss a lot too.

Most importantly, economic theory rarely, if ever, recognizes public policy challenges from the perspective of politicians - the ones who actually are responsible for drafting and implementing such policies. This is a shame because they have a different set of goals, foremost of which is maintaining stability among the body politic.

Michael Pettis highlights how the phenomenon is playing out in China:

I think China will indeed follow, and possible exceed, the Japanese path, but not because it is economically the best solution but rather because it is politically the least disruptive.

While it is easy to lament the suboptimal outcomes of policy beholden to political drivers, it is also easy to under-appreciate the real constraints on political leaders by people who have no such responsibility. Bottom line: Expect the problems in China, Japan, the US and elsewhere to drag on longer than you think they should.

Commodities

Last week I said, “The mixed data on inflation, the lack of prominent market narratives, and the pattern of trading ranges for stocks, all point to an environment where very few assets are moving very much.” Nowhere are the mixed messages more evident than with commodities.

A pervasive fear for all commodities is weakening economic growth. As Rory Johnston points out in his excellent Commodity Context Substack:

For those concerned about the current state of global oil demand, the diesel market is flashing critical warning signs. Diesel margins have plummeted over the past three months from more than $40/bbl to less than $20/bbl. Even more concerning, diesel prompt calendar spreads are in their deepest contango since mid-2020—you know, when the entire world’s transportation sector was frozen by pandemic lockdowns.

At the same time, Dr. Copper (with the PhD in economics) has been ripping higher along with other industrial metals.

Paulo Macro describes in his excellent Substack this is happening because physical supply is short:

Last Friday May 3rd, GS published a detailed copper note featuring some great charts and making a case for why prices need to rally notably by year end to avoid a global physical stockout. In their view, visible stocks should plunge from here:

Importantly, in the three instances of 2009-2011, 2016-18, and 2020-22, speculators positioned bullishly, and then the physical market caught up and confirmed that position. This seems to be happening again now, and it’s showing up in the futures curve.

This is a pretty important development. It means the long-term supply issues that commodities nuts have been arguing about for years are finally starting to hit, even though demand from economic growth is not particularly strong. It also suggests we are in the very early innings of a commodities bull market and that other commodities will undergo similar surges as their physical markets tighten up.

Investment landscape

While slowing economic growth still presents a risk to commodities and other economically-driven assets, it is becoming increasingly evident supply and inventory deficiencies are weighing heavily as well. This emerging reality is indicative of a couple of important trends.

First, is a new pattern of price discovery. When commodities and financial derivatives are abundant, price discovery is largely a function of interest rates, liquidity, and relationships with other economic variables (i.e., the latticework upon which speculative narratives can be built). This is because derivatives markets swamp the markets for physical commodities. An excellent example of this is the (historical) relationship between gold and real interest rates.

When supply starts getting tight, however, financial bettors cannot deliver the physical commodity, those commodities move to buyers who want the physical, and the market toggles to a very different price-setting dynamic. Again, gold is an excellent example as demand for physical gold in China has been a key factor behind its recent price surge.

The second trend is really just an extension of the first. At a high level, and in a very general sense, the stronger the link between physical supply and demand, the better the price discovery. Conversely, the weaker the link between physical supply and demand, the worse the price discovery. This applies to all assets.

It appears China is well aware of this dynamic and has been strategizing to force a transition to physical price discovery. Commodities Substacker, Alyosha, reports:

“China, the present owner and proprietor of all base metals trading save the Comex, seems to have separated America from its certifed [sic] stock.”

In other words, what used to be a gentlemanly game of promises and IOUs is transitioning to a grittier world that involves either having a physical commodity or not. This isn’t deglobalization so much as definancialization and dedollarization.

One point is supply chains and inventories are going to have to get tightened up or there will be severe shortages of certain commodities along the way. Obviously, this is also likely to cause commodity prices to go up, all else equal.

Another point is that while we are already seeing the impact in important metals like copper, the stock market is looking right past any threat of inflation. Hmmm, I wonder how long that will last?

Portfolio strategy

When a very successful investor identifies a major trend, it usually pays to listen. When that trend dovetails exactly with what you have observed and questioned, it’s probably best to give it serious credence.

As Russell Clark laments, something is off; macro isn’t really working and hasn’t been for a while:

What I am starting to think, and with ample evidence, is that macro does not really matter that much. Industry and politics is the key ultimately.

I like shorting, but when I look at short ideas that have worked over the last few years, they have been driven by industry not macro analysis. Chinese tech was a good short because I read that the government was going to regulate them properly.

The first point is I’ve noticed a similar phenomenon; a number of macro trade ideas have been far less effective than they should have been. For example, in 2022 I identified geopolitics as key driver and one that would lead to higher rates and lower asset values. That worked brilliantly, but only for nine months. After the gilt crisis in the UK, markets opened right back up.

More recently, I’ve argued long-term rates are likely to go higher due to significantly higher funding needs, ongoing monetary debasement, and the need for a steeper yield curve to stabilize banks. While all of the fundamentals continue to point in that direction, longer-term yields seem to only go up begrudgingly and often fall right back down on the most tenuous evidence.

I agree with Clark that politics is a big part of this phenomenon. As I have mentioned several times in the past, the Biden administration has a tight rope to walk between catering to labor by being supportive of higher wages and maintaining control of the Treasury market by preventing long-term interest rates from jumping too high. In times of stress, the latter has been favored.

For a hedge fund investor like Clark, time is of the essence and underperformance cannot be tolerated for long. As a result, it makes sense for him to de-emphasize macro and refocus his efforts on areas where the political and industry trends not only work in his favor, but work quickly. Longer-term investors have the luxury of being able to be more patient, but would do well to heed to the mysterious impotence of macro.

Implications

A couple of years ago my vision for the market was one of “controlled demolition”. There was a need to normalized interest rates, but carefully, without initiating a disruptive unraveling.

Now I am coming upon a different vision. Although the rate normalization has continued, liquidity normalization has mostly stopped. Now I see the market as a leaky bucket. The Fed and the Treasury will make sure to keep the bucket mostly full, but there are holes where things leak out.

This ties in with Russell Clark’s assessment of the landscape. The bucket (macro) isn’t going to drain suddenly (i.e., the market isn’t going to crash), but there are holes (politics and industry) where stocks can underperform. Woe behold any stock that isn’t protected by politics or macro necessities.

One implication is that macro bets for or against the market as a whole are unlikely to do very much. In an environment where government policy is dominant and intrusive, extreme (read destabilizing) market moves won’t be allowed. No need swinging for the home run if you never get a good pitch to swing at.

However, another implication is that in specific situations, poor fundamentals can actualize in poor stock performance. This implies a better approach would be “small ball” (i.e., hitting singles and stealing bases). This requires a persistent effort and a lot of concentration but looks like the best way to take advantage of the opportunities that currently exist.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.