Observations by David Robertson, 5/9/25

It looks like we are back to the tariff a day world. Hope you enjoyed the break! Let’s dig in and figure out what’s going on.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

The Taiwan dollar was the talk of the town over the weekend and coming into the week. PauloMacro’s post shows what happened:

There are a lot of things going on here and lot that isn’t yet known, but suffice it to say, Taiwan owns a lot of US Treasuries and this isn’t a good sign for the US dollar (USD).

With all of the market volatility this year, one thing hasn’t changed; corporate buybacks are raging. Almost Daily Grant’s (May 6, 2025) reports:

Make room, dip-buying retail degens, Corporate America’s buyback machine is humming. Citing data from Birinyi Associates, Bloomberg relays that announced share repurchase programs reached $233.8 billion last month, trailing only April 2022’s $242.7 billion for the largest single month dating to 1984. Through May 2, the year-to-date tally reached $665.8 billion, some 10% north of 2022’s prior high-water mark.

This near-record level of buying clearly helped prevent selloffs from inflicting even more damage so far this year. In addition, actions speak louder than words: All that cash going into buybacks was not going into capital expenditures to re-industrialize the country.

As we make our way through earnings season, precious little about results has made news headlines. That doesn’t mean the results haven’t revealed important information for investors, however. The chart below from The Daily Shot shows “Downward earnings revisions for S&P 500 firms have spiked to levels not seen since the pandemic or the Global Financial Crisis, in sharp contrast to international peers, where revisions remain within historical norms.” It seems the adverse conditions are finally beginning to manifest in lower earnings.

Economy

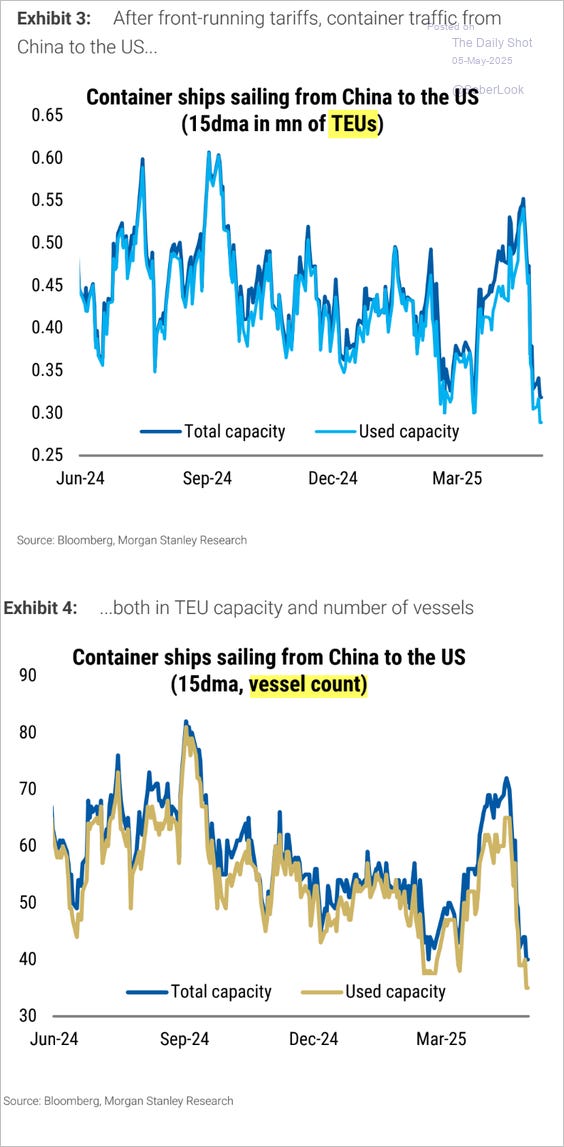

There has been a lot of discussion about how dramatically trade is slowing due to new tariff policies and surely this is an extremely important economic factor. The graph below by The Daily Shot, however, adds a wrinkle or two to the narrative.

First, the dramatic decline that has been reported should be kept in perspective. It is only a dramatic decline from the local highs just a few weeks ago. The latest reported container ship numbers are only about at the local lows of a month and a half ago.

By the same token, a huge burst of activity occurred in early April which reached nearly the highest levels in the last year.

It seems pretty clear a number of firms front-loaded a bunch of inventory building in order to avoid tariffs. That suggests the massive decline in recent weeks is overstated, and companies will have excess inventory for some period of time.

Since tariffs also seem to be a daily topic of discussion and ever-changing, the recent volatility indicates how much harder it is going to be for companies to manage inventory efficiently and how many things can go wrong in that process.

Commodities

Commodities have mainly been falling with the major exception of gold. The easiest interpretation is that of rapidly slowing global growth. As EndGame Macro emphasizes, though, it’s more than just a growth scare: “It is the first structural rollover in U.S. real output under the weight of sustained monetary tightening, rising debt servicing costs, and fiscal exhaustion.”

This should sound alarm bells for all involved. Namely, these are deeper problems than a run-of-the-mill cyclical slowdown.

There is even more to the story though. As EndGame Macro highlights in another post, broadly lower commodity prices are also masking a future in which their availability becomes a critical issue:

While market participants celebrate “disinflation” and falling food prices, strategic actors particularly sovereign nations like China and India are quietly accumulating physical resources.

The liquidation of paper commodities by speculators contrasts sharply with the real-world behavior of sovereign buyers, who are treating collapsing wheat prices as an opportunity to fortify food security amid a fragmenting global trade environment.

This suggests a couple of possibilities that may be causing commodities to be sending a false, or at least mixed, signal. One is that the unwinding of a highly financialized world order has at least at much to do with weak prices as supply and demand fundamentals. Another is that low prices may be used strategically to affordably secure long-term supply.

These possibilities also illustrate why investing in commodities can be so hard. The really big moves are often preceded by sharp moves in the opposite direction. It takes a certain temperament to be able to tolerate such swings, even when you know it will be worth it in the long-run.

One thing that can help is to watch the ascendance of gold. As the premier store of value, gold is really the foundation of the commodities story. It’s price is saying markets are transitioning to a world in which real assets are favored over financial ones. Other commodities aren’t there yet, but that doesn’t mean they won’t get there. It’s a great time to be doing some legwork.

Politics and public policy

Somehow the budget bill, which is one of the most important factors shaping the investment environment, has managed to stay mostly in the background. This piece from the Atlantic ($) provides some useful updates:

This bill would extend the 2017 Trump tax cuts at a cost to taxpayers of some $5 trillion. It would surge funding for Trump’s southern-border plan. It would increase military spending. It might reduce or eliminate taxes on tips, overtime pay, and Social Security benefits.

the options here are either a success that threatens to tank the economy or a failure that tanks Trump’s agenda and also possibly the economy … The third option is to do a more fiscally responsible bill, which would extend the tax cuts but offset them with either spending cuts or tax increases elsewhere. But that’s not likely to pass, because Republicans do not like tax increases of any kind

By my reading, the odds are that a budget bill passes, but it will be one that tanks the economy. This is probably why we haven’t heard more about it.

One point is, “It’s a really big deal”. Yes it is. Another point is it really can’t be put off due to midterms next year. As the Atlantic says, “It really is 2025 or bust”. So, sometime over the next few months, we’re going to get a budget bill that could jolt markets.

A good way to keep score is by watching the spread between 2-year and 10-year Treasury yields. As that spread increases (i.e., steepening), it indicates greater skepticism in regard to prudent financial management. Is also indicates increasing financing costs for the economy.

Investment landscape I

Mention the role of the US dollar (USD) in the world and, as with so many issues these days, you tend to get responses mainly at opposite extremes. Either USD is by far the dominant global currency with no competitor even remotely close to it or it is a crumbling fiat currency just waiting to be vaporized by hyperinflation. Helpfully, Ken Rogoff adds some much-needed perspective to this debate.

As he notes in the Economist ($), the US dollar has actually been gradually losing status on the global stage for several years. Judging a currency’s “footprint on the global economy” to be “what currency central banks focus on as their exchange-rate anchor or reference currency,” Rogoff figures USD has been in decline since around 2015.

Another point Rogoff makes is that USD did not achieve its dominant status through pure superiority alone; it also had luck. He lists as events that just happened to go USD’s way as, “the collapse of mid-1960s Soviet economic reforms that might have turned the country into something more like latter-day China; Japan’s mistake in allowing itself to be browbeaten in the 1985 Plaza accord when its monetary-policy framework and financial regulators were not yet ready for prime time; and the euro zone’s decision to prematurely include Greece”.

However, Rogoff highlights, “The biggest challenges to dollar dominance come from within, including America’s unsustainable debt trajectory.” This is probably at least in part what Warren Buffett was referring to when he said there could be things that would happen in the US that would “make us want to own a lot of other currencies.”

The threat extends beyond just the fiscal trajectory though. Kevin Coldiron ($) addresses some of the “softer” drivers of dollar dominance such as “the US economy’s openness to trade, an established rule of law that is favorable to creditors, a university system open to foreign students whose families accumulate dollars to support and an economy that is the largest destination for immigrants.” Rogoff agrees these drivers are also being seriously undermined but clarifies, “the dollar is not going to go from its giant share to nothing overnight because there’s not any substitute…but you listed the reasons why it’s going to go faster.”

In sum, Rogoff sees the dollar losing status, but not completely. He summarizes, “Mr Trump did not start the dollar’s decline, but he is likely to prove a powerful accelerant.”

Investment landscape II

As politics has increasingly imposed itself on the economic and financial landscape, it has become increasingly important for investors to be able to navigate. Unfortunately, at the same time, it also introduces a great deal of narrative bias into the analytical endeavor.

One way in which I have tried to overcome that bias is by deploying artificial intelligence tools to analyze politics. For example, I prompted ChatGPT 4o to evaluate Trump administration policies through the POSIWID (the Purpose Of a System Is What It Does) framework.

On economics, the output was: “The outcomes indicate that the administration's protectionist policies have led to economic instability, challenging the narrative of promoting economic growth.”

On civil liberties, the output was: “These actions suggest an underlying objective to suppress dissent and control narratives, undermining principles of free speech and press freedom.”

While these analyses should definitely not be considered infallible, they also should not be considered inherently biased in any important way. As a result, they can be used to gauge the objectivity of one’s own analysis and to build or retest conviction.

One idea that leaps out at me is the assessment that the Trump administration’s economic policies “have led to economic instability,” contradicts the administration’s narrative “of promoting economic growth.” How can the administration not know this? If it does know it, why isn’t it doing something different?

Another idea that leaps out is the recognized tendency “to suppress dissent and control narratives,” in addition to being harmful to civil liberties, is also antithetical to rigorous analysis. Without good analysis, there shouldn’t be any meaningful expectation of good policy.

Putting the pieces together makes it increasingly clear that Trump administration policies do not have a good chance of improving the economy. That is something extremely relevant for investors (and consumers and workers) to be aware of and to plan for. This also begs the question of why the Trump administration’s actions thus far are incompatible with its stated objectives. Does it have a different agenda than what it says?

Investment landscape III

Any bias, including political bias, can lead investors to make bad decisions. This snippet from Bruce Mehlman provides some useful perspective on how to constructively deal with political bias:

Analysts need to resist personal bias in their assessments. Trump detractors may mistakenly think that the President shares their conviction that he’s failing (he doesn’t) and give up on policies they don’t like (he won’t). Supporters may mistake objective market signals for partisan criticism, missing critical signals amidst the noise.

In short, there are two different ways in which political bias can cloud one’s analysis of the investment landscape. Trump detractors may believe the Trump administration observes the same negative data they do and believe he will give up on those policies. As Mehlman highlights, that is unlikely to be the case. Trump simply does not share the same conviction that he’s failing. This implies his policy direction will continue until it is forced to do otherwise.

Trump supporters, on the other hand, run the risk of interpreting negative market signals as merely partisan criticism. Persistent failure to recognize when risks are building can lead to painful losses. The market doesn’t care what one believes.

At the end of the day, most people don’t modify their behavior on this kind of advice though. Rather, it usually takes the cold, hard knock of experience to teach that lesson. As a result, it may be foreign investors, who have a less visceral reaction to Trump, who are least affected by bias and begin reacting to the changes in the investment landscape first.

Investment landscape IV

In a recent note by Russell Clark ($) discussing the start of his new hedge fund, he finds the biggest skills gap he has to fill is “Someone who can marry politics and markets - and see where the opportunities lie”.

I find this interesting for a number of reasons. For one, it recognizes the increasing influence of politics (and geopolitics) on the investment landscape. This corroborates the claim I made in the Outlook piece earlier this year.

For another, it highlights the challenge so many investors face buy maybe don’t recognize so consciously. Most of what research is available, including most macro research, used to work but doesn’t work very well any more. This leads to a lot of bad takes and misdirection. Investors who can incorporate a political and geopolitical perspective into their analysis will be able see things others can’t.

The opportunity is especially ripe because not only do most asset managers and research shops avoid political research, most even reject the notion that it is useful. In other words, there isn’t a lot of competition.

For what it’s worth, I have a slightly different take on macro and political analysis than Clark does. I think both are forces than can affect the direction and behavior of markets. Just because macro may not be working great doesn’t mean it isn’t an important factor. Indeed, I would argue macro constraints are a huge factor in driving both the degree and nature of political intervention. Macro often represents the challenges and politics represents the way to navigate them. So, it’s not one or the other; it’s one in relation to the other.

Finally, it’s a good time to be thinking about politics in analysis because it appears as if policy orientation is changing. After the GFC, central banks were clear they wanted investors to take on more risk. During Covid, the Biden administration made clear that it was using fiscal stimulus to moderate the negative consequences of shutdowns. I both cases, official statements were consistent with, and conducive to, investors’ desires.

That is now changing under the Trump administration. While it speaks of goals of promoting growth, its policies thus far have mainly caused greater instability. This may change over time, but for now investors should be aware that simply following Trump administration statements may not be in their best interests. Politics is definitely becoming an increasingly important dimension of the investment landscape.

Implications

Insofar as the Trump administration is creating economic instability, despite its promise of economic growth, the negative effects will show up in the numbers and they will make things worse for most people. Insofar as these efforts continue, USD will continue to get weaker which will reduce its purchasing power and make things worse for most people.

These insights also reveal the uphill battle facing Scott Bessent. If he starts acknowledging the instability and addressing it, he reinforces credibility with investors but risks losing the support of his boss. If he continues promoting the administration’s line of future success without also acknowledging elements of policy that cause instability, he risks roiling markets which are already on edge. The task is doubly hard to accomplish with foreign investors while also promoting an “America First” ideology.

The FT’s Unhedged ($) newsletter captured much the same line of thinking: “And just stating this goal (US re-industrialization) makes clear how wildly ambitious it is, how huge the required changes are. The big worry is not that the Trump administration’s goals are conceptually incoherent. It’s that they are really hard to achieve.”

In my opinion, the goals are also incoherent, but that doesn’t matter. What matters is there is a gap a mile wide between the administration’s economic goals and its plans to achieve them.

Right now, it’s probably fair to say Bessent is the fine thread keeping high market expectations tenuously tethered to vague administration claims of progress despite its actions which seem to be working at cross-purposes. Nor does this seem to be just a random glitch.

A lot is riding on the narrative and belief that Bessent will be able to work things out. The odds are stacked against him. If and when he falls short, there won’t be a lot to keep financial assets from falling hard.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.