Observations by David Robertson, 6/27/25

There is plenty going on behind the scenes even as volatility melts and stocks gently rise. Let’s dig in.

Also, Observations will not be published next week due to the holiday. I hope you have a wonderful Fourth of July!

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

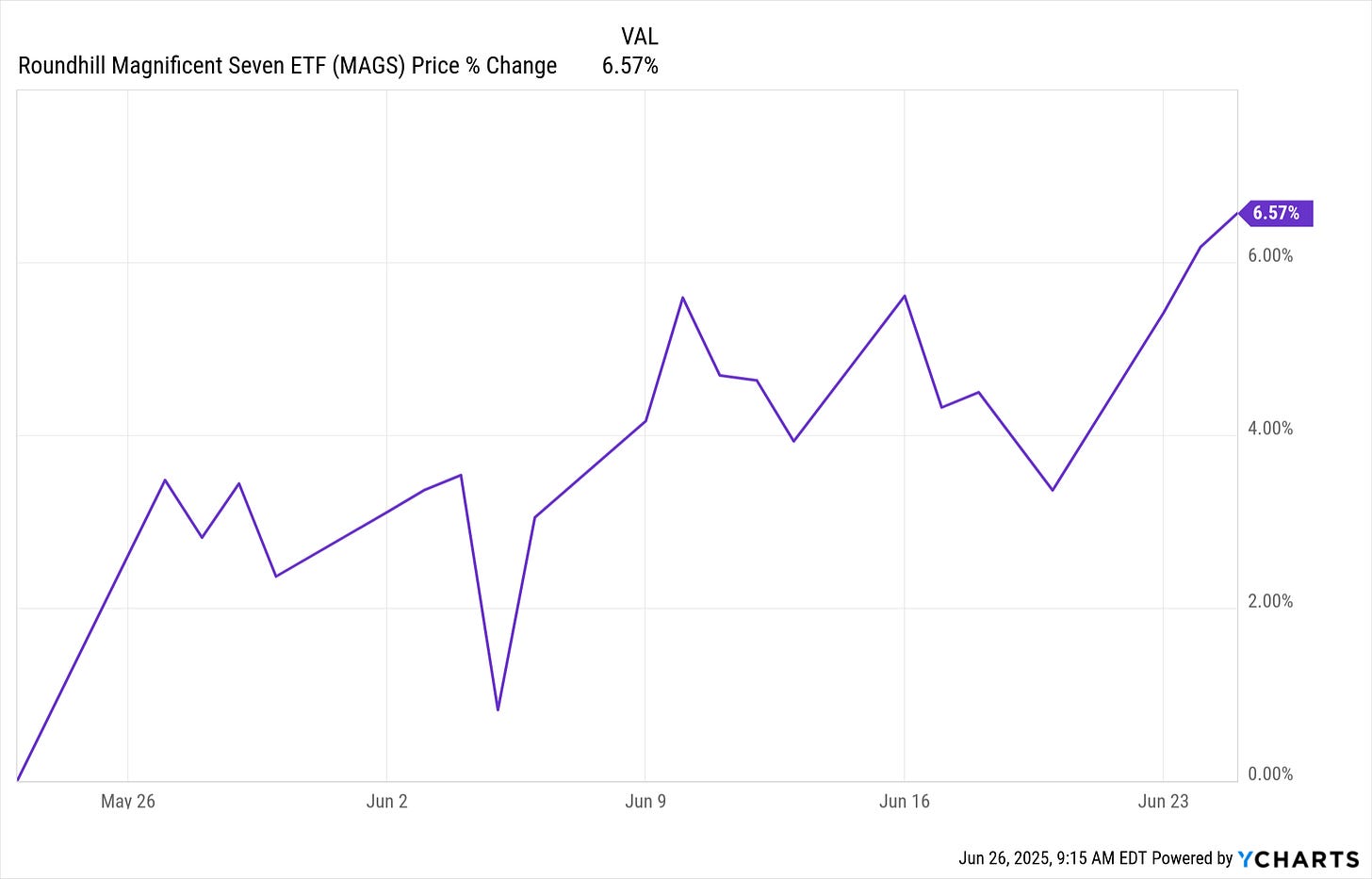

As stocks have nudged higher over the last month, the main driver has been the Mag 7 stocks. When market volatility declines and there is no other obvious theme, they are still the go-to destination for money flows.

At the same time, the US dollar (USD) is hitting the lowest levels in years as of Thursday morning on the news of a short list of replacements for Jerome Powell as chair of the Federal Reserve.

As we await the expiration of the “pause” period on liberation day tariffs in early July, Michael Pettis reports on one adaptation China has made due to increased constraints on trade: A government-backed grey market “registers new cars right off the assembly line and then ships them overseas as ‘used’ vehicles.” This serves the purpose of allowing “Chinese automakers to show growth and to dispose of cars that it would be difficult to sell domestically.”

Unfortunately, it also drives down prices and floods foreign markets with unwanted cars. But the numbers look good for now!

Politics and public policy I

The US bombing of nuclear enrichment sites in Iran was all the news over the weekend. While the geopolitical consequences are still largely unknown and are likely to play out over time, Jonathan V. Last ($) notes the event does reveal some important insights about the Trump administration.

For starters, there is no clear strategic objective of the exercise. SecDef Hegseth stated, “This mission was not and has not been about regime change” on the morning of June 22. Last reports that nine hours later, Trump posted on social media about regime change.

Last also notes that “peace” would be a perfectly acceptable goal, but according to Trump, Iran’s nuclear program was “completely and totally obliterated”. As a result, Iran has nothing to concede. In short, the inability to form a clear, cohesive statement about war aims suggests other motives were in play.

In addition, high level statements about the bombing conflict with one another. According to Last:

the president and secretary of Defense say that Iran’s facilities were “completely and totally obliterated,” and that Iran’s nuclear program has been “dealt the final blow.”

Meanwhile,

The chairman of the Joint Chiefs says that it is much too early to give any sort of accurate assessment of the damage done.

Last rightly concludes, “Either the general, or the president and his SecDef, are lying to the American public.”

Finally, Last compares and contrasts these two tidbits:

In March, the Director of National Intelligence [DNI], Tulsi Gabbard, testified that, “The [intelligence community] continues to assess that Iran is not building a nuclear weapon.”

The Trump administration has subsequently claimed that Iran was, in fact, sprinting toward a nuclear weapon. When asked about his DNI’s assessment, Trump replied, “She’s wrong.” And: “I don’t care what she says.”

One observation is the direct refutation of national intelligence smacks of the WMD disaster in George W. Bush’s presidency. Another is that at very least, there is dissention in the administration.

Trump’s response also begs the question of how he makes his decisions. Does he rely on American intelligence or on intelligence from other sources as Jonathan Last inquires? Or, perhaps more scarily, does intelligence even play a major role in his decision-making?

Putting all of these pieces together suggests the whole endeavor was at least partly an exercise of narrative shopping — which means some ulterior motive is the key driver. Last week I said:

The working hypothesis continues to be that the absolute priority of the Trump administration is to pass the budget bill and its attendant tax cuts. Until that is done, all efforts must go to serve that purpose.

As a result, I suggested:

If the working hypothesis holds, we will continue to see more dramatic, headline-grabbing proclamations from the White [House] with the intent of diverting attention away from the budget bill. At the same time, the odds of meaningful volatility events in stocks or bonds that might threaten passage of the bill will remain fairly low.

Thus far, check and check; the hypothesis is holding.

Politics and public policy I

Zohran Mamdani won the Democratic primary for mayor in New York City on Tuesday. Not only was it a dramatic turn of events (Polymarket had Cuomo with a 92% chance of winning as recently as late May), but Matt Stoller ($) tells why the election also has broader implications:

Most elections are conflicts over who will run an existing system, with the candidates offering tweaks to what is essentially a stable political order. But a few elections are what I will call “system defining,” where a rising coalition, reflecting a new set of political demands, contests with an old order, seeking to re-gear the basics of how our institutions operate.

Mamdani’s win yesterday is likely such a system defining election. For as long as I’ve been in politics, the Democratic Party base voters have liked their leaders. They might dislike a scandal-tarred Democrat here and there, but they broadly believed that the Democratic leaders are good, that they meant well, and that it’s mean to pick someone younger or different. It’s why most Democratic leaders are old. Recently, I’ve been seeing polling showing that Democratic voters are unhappy with their leaders, but it’s hard to believe that until you see proof. The heart of American politics are elections, and the election last night just delivered that proof, some undeniable evidence of populist anger on the left.

Stoller summarizes, “There really is a new voter universe, young people frustrated over affordability, and not just angry over partisan affiliations. It’s a system defining election because it’s likely the coalition of voters behind Mamdani exists in every state and city”.

Mamdani’s victory certainly does feel like the political winds are changing. For one, it represented meaningful pushback against the old Democratic order. The Bulwark ($) determined, “It should be a death knell for an ossified Democratic establishment that needs to be put out of its misery.”

To be sure, however, the contest was not just handed to Mamdani. His willingness to engage with voters and to address meaningful day-to-day concerns resonated in a way that came across as fresh and authentic. While it would be a stretch to consider his policy ideas as completely coherent, they consistently touched on themes of populism and anti-monopoly.

It would be a mistake to crown Mamdani as NYC’s next mayor, but it would also be a mistake to dismiss the political importance of his win. It has all the makings of a “regeneracy” as described by Neil Howe in his book, The Fourth Turning, by which political affiliations get re-sorted and reorganized. The people spoke and they want change.

Politics and public policy II

Our Dollar, Your Problem: An Insider's View of Seven Turbulent Decades of Global Finance, and the Road Ahead by Kenneth Rogoff ($)

Ken Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart made a splash with their well-timed book, This Time is Different, in 2009. Their main point was that debt matters. More specifically, when the public debt of a country crosses a threshold of 80-90% of GDP, its growth tends to slow down and that makes it more vulnerable to a financial crisis.

Unfortunately, the warning went largely unheeded as the problem of excess debt was glossed over by monetary policy that suppressed interest rates in the years after the GFC. Low rates were maintained for over a decade thanks in large part to low inflation, the intellectual rationale of “secular stagnation” by Larry Summers, and the narrative creation by former vice-president Dick Cheney that “deficits don’t matter”.

Low rates made it easier for everyone to borrow, including the government. As Rogoff describes:

The idea that U.S. debt is a cow to be milked became common wisdom throughout much of the economics profession, which led to a sea change in views among academic economists on the role of fiscal policy.

As a result, the fiscal deficit started creeping up (as a percent of GDP) and exploded with Covid. While the deficit has shrunk somewhat since Covid, it has remained higher than any period outside of war time.

Now, with his new book, Rogoff is issuing a new new warning — that excessive debt and deficits are unlikely to be sustainable and that the investment and public policy communities are overly complacent about the risks. More specifically, he notes, “with interest rates normalizing (outside recessions), the jig is up.”

Relatedly, Rogoff explains views on inflation are also overly complacent:

There is also unwarranted complacency concerning inflation. Economists have convinced themselves that high inflation is a solved problem. As a technocratic matter that is true, but the political economy roots of inflation remain, which is why another bout of high inflation over the next five to ten years is not only possible but likely, especially if there is another major shock such as a cyber war or a pandemic.

While academics and investors alike have become anchored on the belief in low inflation and low rates, Rogoff highlights these beliefs are failing to account for important changes in the landscape. Namely, with the constraints of excessive debt and fiscal deficits, there is now extremely little room for public policy to forestall or avoid the consequences of higher inflation, higher rates, and a weaker US dollar.

Rogoff was even more forceful in an FT ($) summary of his book that went under the headline, “America’s fiscal policy is going off the rails — and nobody seems to want to fix it”. In that, he concluded, “The US’s high debt and inflexible political equilibrium will be a major amplifier of the next crisis and, in most scenarios, the American economy and the dollar’s global status will be the losers.”

Politics and public policy III

Interestingly, Russell Clark ($) recognizes the very same phenomena as Rogoff, but describes them from the perspective of a practitioner.

Well the bull market we have seen since 2009, for me, has in many ways had a “private equity” feel to it. What do I mean by that? Well until 2016, it was typical for US fiscal deficits to fall as employment and stock markets rose. “Save in the good times, spend in the bad times” mentality has been replaced with “If we can borrow cheaply, then why don’t we?” mentality.

Well there are obvious signs of a slowdown everywhere. The Russell 2000 has gone nowhere for 5 years now … And the Trump administration will likely look to stimulate the economy, which would worsen the inflation outlook, so should see foreign investors dump the long end of the treasury curve. That is I would expect to see the curve steepen radically.

One major observation is that the public policy strategy of borrowing cheaply is “a one time win. And once its done, it take a lifetime to fix.” Sure, it provides an extra boost for several years, but then it takes “a lifetime to fix”.

Another observation is that Clark has a motivated interest in this; it’s not just an academic theory. He just started a new fund designed to benefit from a normalization of the excesses that have developed. The fact that both Clark and Rogoff are sending out virtually the same message lends credence to the notion that time is running out on public policy “fixes”. That means the time is nearing for the consequences.

Investment landscape I

US dollar’s slide in April 2025: the role of FX hedging

https://www.bis.org/publ/bisbull105.htm

A large share of this investment [i.e., portfolio investment by non-US investors since the GFC] has been in US dollar assets, especially equities listed in the United States and long-term debt securities (Graph 1.A). To some extent these dollar holdings reflect the size and multiyear outperformance of US capital markets.

The reduction in FX hedge ratios in recent years can be attributed to at least two factors. One is high hedging costs, which tend to favour unhedged positions. FX hedging has become more expensive since 2022 (Graph 2.A), when the US Federal Reserve began its most recent hiking cycle, leading to an increase in the short-term dollar interest rates … A second factor discouraging hedging was a bullish view on the US dollar.

One of the prominent narratives floating around is the notion that international investors in US assets will repatriate their US investments as investment conditions in the US become progressively less friendly. A number of sell-side research pieces have jumped on the opportunity to show this isn’t happening, at least not yet. As this report from the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) shows, however, there are strong indications the process is starting.

First, the BIS provides some helpful background. Since the GFC, the BIS notes, “private investors have replaced official institutions as the largest foreign buyers of US securities”. In this case, private investors can be thought of as pension funds and insurance companies.

This is important because these institutions manage local liabilities against global assets. As a result, asset allocation is important, but so is currency exposure since liabilities must be met in local currency. Because returns on US assets since the GFC were generally very good, a lot of private investors did not hedge US dollar exposure.

As concerns about US investments have risen under the Trump administration, however, these private institutions are re-evaluating US holdings. Since changes to asset allocation normally happen only gradually, over time, the first step in risk management is to hedge the US dollar exposure.

This is exactly what the BIS observes to be happening: “Changes in the cross-currency basis between March and April/May 2025 are consistent with higher demand to hedge dollar investments.” Further, the BIS reports, “Investment fund data for April and May indicate continued inflows into US assets, albeit at a slower pace”.

In short, the weakness in the US dollar this year is a strong leading indicator that large foreign investors in US assets are moving toward the exit. As investment committees eventually reduce allocations to US assets, the move to the exit will pick up pace. Just because outflows haven’t happened yet doesn’t mean the process hasn’t started.

Investment landscape II

A good chunk of the investment community has been cheering lower inflation numbers lately and therefore arguing for interest rate cuts by the Fed. As I have highlighted several times, however, the risk of higher inflation is increasingly also a supply issue. Nowhere was this more apparent than the brief jump in oil prices when the conflict in Iran threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz.

Although it’s not currently making headlines, Shannon Brandao ($) points out the supply issue is still very much alive with rare earth elements:

The United States and China reached for détente in London barely two weeks ago, sealing a fragile handshake deal to pause their spiraling trade war.

But behind the official exchange of pleasantries, one vital issue remains unresolved.

China has not resumed export licenses for defense use of rare earth magnets, the linchpin of U.S. missile systems and stealth aircraft.

Brandao goes on to report that “China has tightened its grip on their [rare earth elements] global flow” and this has resulted in “delays, shortages, and a creeping unease in Western capitals”. She concludes that “strategic resources are no longer just for sale”.

So, how does one account for the price of something that simply cannot be purchased? Partly by the time and investment needed to replicate the product. Partly by the loss of military and industrial power caused by its absence. Partly by the cost of imperfect substitutes. Partly by the cost of diverting resources away from other activities to compensate.

While none of these factors appear in recent inflation numbers, each of them will have a material affect on the economy going forward. So for one, supply matters to the inflation outlook. For another, strategic and qualitative factors can be among the most important factors in developing an inflation forecast.

Investment landscape III

Based on investment commentary in traditional and social media, many investors still harbor the belief that stock prices are determined primarily by fundamentals. As a result, there is always an opportunity to make money by recognizing trends ahead of other investors.

For better and worse, this is no longer a very accurate depiction of what drives the stock market. The following illustration by Alyosha ($) shows not only how much markets have changed, but how the very proposition of investing has changed:

So … what about stocks? Technically, the old stock market is dying. Open interest is making multi-year lows this month. Volumes are always just enough to economically regulate prices.

Humans have been deaccessioned. All price discovery is being done in server farms and dark pools by financial firms that haven’t had a losing day in many years. Equities are not investments, in my opinion. They are devices to separate the unsophisticated hosts from their money in tiny slices day by day and huge hunks in the occasional crash.

Observation number one is this sounds a lot like Ben Hunt’s theory of the stock market as a public utility. According to that theory the stock market serves a useful purpose to policymakers by keeping collateral afloat and therefore underwriting consumer spending — which is the bulk of the US economy. As a result, keeping the market levitating is a policy goal because it keeps the economy chugging ahead.

The fact there is such a strong incentive for policymakers to maintain the stock market shows both why stocks aren’t really investing (because there isn’t really price discovery) and why it is so hard to make money (the real money is made by intermediaries on transactions/flow).

What lessons should be taken from this? Number one, frequent trading mainly just contributes to Ken Griffin’s already-substantial retirement fund. Number two, while policymakers have a strong incentive to keep stocks afloat for as long as possible, that goal is increasingly coming into conflict with the threat of higher inflation and with the diminishing capacity of policymakers to support stocks. Some day, and quite possibly in the next couple of months, investors are likely to get a taste of what the stock market is like when it tries to survive in the wild on its own.

Implications

Extraordinarily low interest rates in the post-GFC period helped ignite a tendency for risk-taking among investors that has persisted to a large degree even as rates have normalized since Covid. Older investors are desperately trying to grow their pile of savings for retirement and younger investors are aggressively seeking to grow wealth in an environment where there is a dearth of good alternatives.

Unfortunately, the widespread orientation to risk-taking and growth is poorly suited for an environment in which prices are stretched, complacency is widespread, and public officials are running out of options to continue support for capital markets.

By far the most important thing investors can do in such an environment is to avoid the meat grinder of negative returns. Part of that involves managing risk more deliberately and part involves checking the tendency to keep reaching for more.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.