Observations by David Robertson, 6/28/24

Since the Fourth of July holiday is in the middle of next week and I suspect a lot of people will be away, I'm going to take the week off as well. Observations will be back on July 12. Until then, enjoy!

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

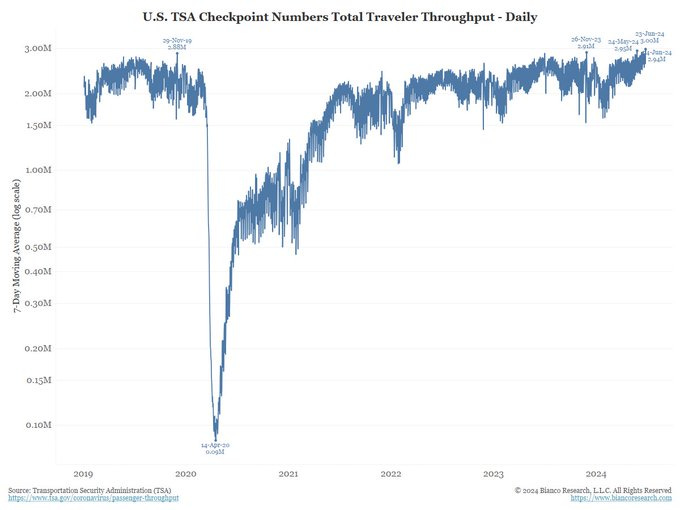

Among the bits of data coming in that suggest a mildly weakening economy, Jim Bianco recently posted a bit of disconfirming evidence: Air travel is setting new records. He notes:

Sunday was a new all-time daily high at 3 million travelers.

The 7-day average is also a new all-time high. ---

Nothing is more discretionary than personal travel. When things turn down, it is the first thing to be cut.

So, what does this say about the economy?

This corroborates a couple of points I have repeatedly been making. One is that there is a lot of mixed economic data and it’s likely to remain that way for some time. The other is that there are still big chunks of the population that continue to spend freely. No easy answers yet.

Relatedly, as economic data is coming in weaker on the margin, long-term yields are coming down and bond bulls are getting fired up again. Given that I have repeatedly expressed the longer-term strategic position that bonds are not a good bet, I couldn’t resist mentioning this choice quote from Russell Clark ($):

I see plenty of analysis of why now is a good time to buy bonds, and how interest rates are going to get cut etc. To be incredibly harsh - most of it reads like old men having a hard time accepting that the world has changed.

Another interesting observation during the week was the fall of the Japanese yen (JPY) to more than 160 to the US dollar (USD). This is a level at which a number of commentators presumed the Ministry of Finance (MoF) would intervene, but since it didn’t, it suggests Japan is not unduly troubled with the depreciating currency. As a result, it is easy to interpret the lack of action as a policy of monetary debasement.

Politics

This little blurb by Brad Setser packs a lot of punch in terms of highlighting underlying political problems in the US:

Sometimes I wonder why there isn't a bit more populism in US politics.

Big Pharma (6 major US pharmaceutical companies) literally collective paid no corporate income tax in the US in 2023 ...

He goes on to document the main problems this causes:

And there are two concrete harms to the US economy from all these tax games --

- Lost tax revenues. $70b in profit at 15% is $10b a year;

- Lost production jobs, as profit shifting usually requires offshoring production

Russell Clark ($) also acknowledges US tax policy is a big problem when he says, “US tax policy, makes sense for US politicians and US corporates, but not for any one else.” He goes on describe, “the current situation is so good for large corporates, and government finances are so parlous, and voters are so disenchanted …”

To me, this pinpoints a big underlying problem: Not only is current tax policy manifestly unproductive economically, it is manifestly unfair to the populace. If people want to get fired up about something, this should be at the top of the list.

Indeed, Setser sees the possibility of a “win/win” opportunity to create an “‘America first’ set of reforms that would change the corporate tax code so that American pharma companies actually pay tax in the US on the US sales (and don't pretend to lose money in the US ... )”. Clark, on the other hand, doesn’t believe government has any sway to “bring corporates to the table”. As a result, he thinks the result is higher deficits for as far as the eye can see.

Another way to view Clark’s position is that since it is virtually impossible to remove the tax advantages that corporates currently enjoy, the only viable political option is to shower other important political constituencies with redistributed wealth. In other words, share the grift.

This highlights one of the most frustrating aspects of the political environment right now. While perfectly viable economic and social policy solutions exist, many are not yet politically viable. Until they are, government finances will continue to get worse.

Geopolitics I

One of the overriding themes I have been emphasizing is that geopolitics is taking a central role again in shaping the economic and investment environment. Two recent reads that have focused on the subject are New Cold Wars by David Sanger and Global Discord by Paul Tucker.

New Cold Wars describes itself as “a book about a global shock that took Washington by surprise: the revival of superpower conflict”. It is “the story of how we misjudged what would happen after the last Cold War ended. But it is also the story of trying to discern ‘what comes next’ at a moment of maximum peril”.

Global Discord pursues two related ideas. First, it explores “how my [Tucker’s] world of economic policymaking had become detached from geopolitics”. Second, it is also “about how the boundaries between policy fields that usually keep a distinct distance from each other—the international monetary system, national security, trade, human rights, humanitarian intervention, the environment, pandemic control, even war and peace—unavoidably blur as governments confront problems of geopolitical grand strategy and domestic political authority.”

Common themes arise in both books. One is the belated realization in policy and diplomatic circles that relations with China and Russia have fundamentally changed. Another is that both countries seem to be playing long-term strategic “games” while the US struggles to formulate any kind of cohesive strategy. Further, such an effort has been constrained by a situation in which “the boundaries between policy fields … usually keep a distinct distance from each other”.

Together, these pieces provide a nice primer on the geopolitical challenges facing the US and the growing implications across other fields … like investing.

Geopolitics II

A recent post by Niall Ferguson touches on many of the same geopolitical points. His primary argument is the US has devolved to a state akin to that of the former Soviet Union. As he puts it, the two have in common “A government with a permanent deficit and a bloated military. A bogus ideology pushed by elites. Poor health among ordinary people. Senescent leaders.” Jonah Goldberg describes it as “vintage Ferguson”.

Goldberg pushes back ($), however, arguing that this vintage of Ferguson came out “darker and more acidic than it should”. While he agrees with the notion that “as a matter of geostrategic competition, we are repeating some of the mistakes the Soviets made,” he also thinks the analogy is carried too far. In one example of many of the substantive differences between the US and the former Soviet Union, Goldberg writes, “the Soviet Union built a wall to keep its subjects trapped inside their evil empire. Many Americans understandably believe we need a wall to keep millions of people desperate to live here out.

Ferguson hits back in a thread on X: “The bottom line is that we need to be much more worried than we are by the shocking degeneration of all our institutions, from the presidency to the public health system. The idea of late-Soviet America is intended to shock people like @JonahDispatch out of their cope.”

So, both writers make important points. Both agree with the notion of a “great power rivalry” between the US and China. This is consistent with the themes of the books mentioned above. Goldberg agrees plenty of things can be better, but argues they aren’t totally hopeless either. Ferguson claims the “shocking degeneration of all our institutions” is of such a magnitude that shock is required to instigate action.

This highlights a kind of political purgatory that serves as a handicap for the US in the great power struggle. Until things get worse, and possibly much worse, there just won’t be sufficient political support in the US to engage Russia and China in kind in the great power struggle - and that poses enormous risks.

Geopolitics III

Another veteran of international relations, Harald Malmgren, has voiced similar concerns about the nature and direction of relations with China and Russia. In one post he noted:

I think the "axis of evil" is increasingly considering ways to weaken and eventually render incapable the ability of the US to respond militarily to respond to threats to its allies, and eventually threats to itself

And in another he added:

When I say the "axis of ill will" has altered its objective to replace the US-led financial and rule-based system, they are now focused on attacking the fast growing US debt vulnerability to crippling international security challenges in more and more locations worldwide.

One point is that “crippling international security challenges in more and more locations” is already happening. For example, just last week, Car Dealership Guy reported, “I’m absolutely speechless. ANOTHER automotive ‘cyber incident’ occurred … CDK again the victim. Dealerships contribute 3-3.5% of GDP and CDK power over 50% of them. All systems are shut down. Again. This feels like a bad dream.” He added, “50%+ of U.S. dealerships rely on this software. It’s the heartbeat of all operations. Will have massive ripple effects on the auto industry and economy if isn’t resolved soon.”

In addition, the FT ($) recently reported, “Silicon Valley companies are escalating their security vetting of staff and potential recruits as US officials ramp up warnings about the threat of Chinese espionage.” The article continues, “Venture capital firms such as Sequoia Capital, which backs dozens of startups, including Elon Musk’s xAI, have also encouraged portfolio companies to tighten vetting after warnings that overseas spy agencies were targeting US tech developers, the people said.” In short, it’s open season on US tech from Chinese spies and US companies are figuring out they need to do something about it.

One takeaway from these examples is that companies are quickly waking up to the business implications of superpower rivalry. Increasing cybersecurity attacks and national security concerns are just a couple of areas that warrant greater attention.

Another takeaway is the electorate has been even slower to wake up to implications of the new geopolitical reality. Many are still grounded in the belief that “hot” shooting wars are the only geopolitical events worthy of consideration. This presents a problem because without sufficient public support, it will be harder for any administration to harness the resources necessary to mitigate the efforts of the “axis of ill will” to distract and weaken the US. The evolution of the American public’s perception of the new state of geopolitical rivalry will be a key variable to watch.

Monetary policy

Markets ignore the politics of central banks at their peril ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/4e5734d4-a0f5-4f3b-8c08-44c80e8319ce

Neither the US Federal Reserve’s Jay Powell nor the European Central Bank’s Christine Lagarde is a certified member of the central bankers’ club. Lacking the economics training and record, they must operate as deft chairs of technocratic boards. Their predecessors — notably Paul Volcker, Alan Greenspan, Ben Bernanke and Mario Draghi — earned the respect of the monetary priesthood; they could debate experts and steer policies based on their own backgrounds. Powell and Lagarde can’t.

As a result, the Fed chair and ECB president are especially reliant on staff forecasts. But these models have not been working well. The resulting uncertainty has created more room for a range of opinions from the bank boards, but not increased authority for the principals. The institutional counter to this drift has been to rely on a supposedly refined, technical approach: “data dependence” — a term that means central bankers don’t know what to do.

This critique of central banks is notable on at least two counts. First, it provides some perspective on recent miscues. The suggestion that Fed chair Jerome Powell lacks “economics training and record” and therefore cannot “debate experts and steer policies” paints Powell’s Fed more as an unruly class with a substitute teacher than a cohesive organization locked into fulfilling its mission. This may explain some of the inconsistencies and lack of decisiveness.

Second, the “special reliance on staff forecasts” also provides some interesting color. The Fed’s economic models are famous for making unrealistic assumptions and failing to comport with real business conditions. This helps explain the Fed’s reluctance to acknowledge inflation in 2021 and its obtuseness in maintaining that financial conditions are restrictive as markets reach new all-time highs.

In sum, the market’s current view of the Fed (and ECB) contrasts sharply with that of Zoellick. The market still treats the Fed (and ECB) as an omnipotent organization that can steer markets and the economy at will. If ever there is a hiccup, it will do “whatever it takes” to get back on track.

Zoellick’s portrait of the Fed shows a weak organization that lacks clear insights or decisive policy direction and therefore repeatedly hides behind the mantra of “data dependency”. This also helps explain why there has been so much focus on short-term rates as a policy lever and so little discussion about the Fed’s balance sheet. No, it doesn’t work, but it’s deeply ingrained habit.

While Zoellick’s critique is probably at least a little extreme, it does provide significant explanatory value in regard to Fed actions and inactions. Most importantly (and scarily), it suggests the market following the Fed for direction is a case of the blind following the blind.

Gold

Since it’s (relatively) big move from the middle of February to the middle of April, gold has bounced around but stayed in a fairly tight range. Like a Hitchcock film, there has been plenty of suspense, even if there hasn’t been so much action.

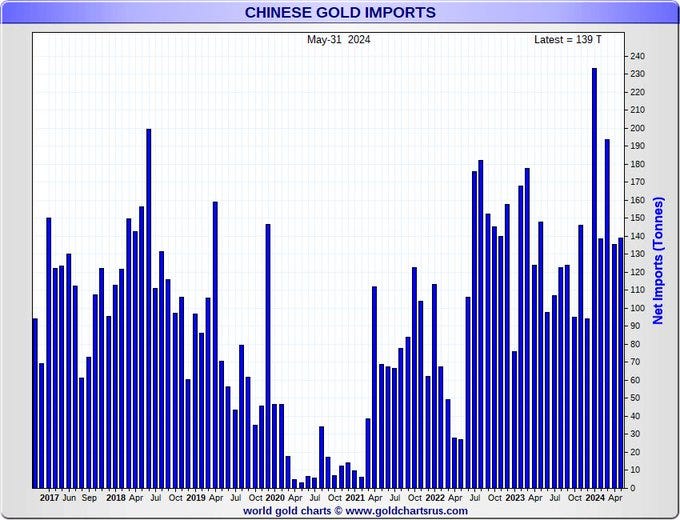

One of the data points that halted the upward momentum was the report that China’s central bank did not add any gold to its reserves in the month of May (which I mentioned two weeks ago). That data point flies in the face of other data that Jan Nieuwenhuijs posted that shows Chinese gold ETFs are rapidly acquiring gold.

It also flies in the face of new data (also posted by Jan Nieuwenhuijs) that shows China continued to import a “robust” amount of gold in May:

This new data suggests a new tweak to an old hypothesis. What if the price of gold is being manipulated, but by China rather than the US? There is certainly motive and means. Insofar as China is on a program to systemically increase gold holdings which it appears they are, it would absolutely behoove them to acquire those holdings at discounts when possible. If all it takes is a little white lie in the form of underreporting central bank purchases of gold, then why not?

The main point to take is not so much whether this specific hypothesis is right or wrong, but to recognize the increasing body of evidence that various governments might be interfering in the gold market. If they are going to these lengths to suppress the gold price, that suggests the natural price is higher, and perhaps much higher.

Investment landscape

Let Them Have Chaos: The ECB, What Sustains The Flight Of The Bumblebee & The Silence of Madame (24/06/2024) ($)

The Solid Ground newsletter by Russell Napier

The ECB having already destroyed three democratically elected devolutionist governments; why would Schnabel choose to politicise the ECB further by marching against Germany’s second largest political party? Are the gloves now off? Was Schnabel’s recent proclamation in Tokyo that QE would not return a clear statement, ahead of the European Parliamentary elections, that the ECB would stand aside if soaring government bond yields were necessary to discipline the devolutionists and the electorates that voted for them?

Russell Napier’s hypothesis that the ECB (European Central Bank) may be siding with pro-Eurozone political interests has enormous implications for the Eurozone, but also has implications that reach across the pond to the US. In other words, when push comes to shove, could the Fed run the same playbook by “letting them have chaos”? More specifically, if it looks increasingly likely Trump will win as the election approaches, might the Fed consider letting longer-term rates run up in order to increase the sense of chaos that might prevail under a second Trump term and thereby tilting the election?

While this possibility may seem outlandish, it is probably less outlandish than it seems at first. For one, Trump’s main pitch that there are a lot of rotten institutions that need to be torn down sells better in an environment of relative wealth and stability. The costs don’t seem very high. In an environment of great uncertainty, however, the prospect of even more uncertainty looks scary and even downright irresponsible. That would undermine Trump’s entire political reason for being.

There was something of an analogue in the 2008 election between Obama and McCain. As the financial crisis metastasized, the candidates had trouble adapting because it wasn’t written into their campaign strategies. While Obama did not seem very well qualified to deal with it, he at least paid some attention to it. McCain seemed almost completely disinterested.

While I seriously doubt “Let them have chaos” is “plan A” for the Biden campaign, it does present an interesting alternative if the race is too close for comfort as the election approaches. We are most likely going to experience some kind of chaos in the not-too-distant future anyway. If it can also serve the purposes of the incumbent administration, it would be naive to rule it out.

Implications

When you add together the notions that the US is lagging in the long-term strategic game of geopolitics with China and Russia, monetary authorities may have little or no ability to cause meaningful improvement in the economy, and politics is rewarding grift for as far as the eye can see, it’s not hard to conclude the US appears to be playing a game of chicken with fate.

While I am not darkly pessimistic in the sense of believing there is no way out of a severe downturn, I am also realistic enough to see that geopolitical parameters affect the universe of potential outcomes in ways that are new and unusually constraining. No longer can the Fed just drop rates to zero if any little hiccup happens to the financial system. Doing so now has geopolitical consequences which could make the US incrementally more vulnerable to attack.

Since the US public is not currently in a state to coalesce against the threats of the new cold wars, I suspect the next few years will be characterized by a growing awareness. As a result, this period will also be characterized by a growing awareness that what happens with markets is no longer dictated by the Fed, but by geopolitical necessities.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.