Observations by David Robertson, 6/9/23

Now that the debt issuance races are off and running, investors are trying to figure out what it means for stocks and bonds. So far, stocks and bonds are both bouncing around looking for direction.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

In markets, something comes of nothing ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/7d90744e-0c32-4233-909c-e0d0f38b4b04

The most significant thing that has happened on Wall Street in the past few months is a reassessment of inflation, and therefore the likely path of Federal Reserve policy.

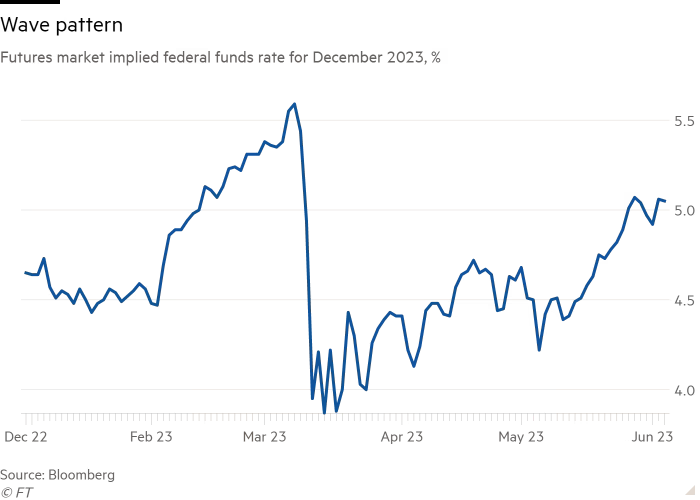

The market-implied federal funds rate for the end of this year has risen steadily since March. Three months ago, the broad consensus was that we had seen the peak, and rates would soon start to fall. Now the consensus is that rates will still be where they are — about 5 per cent — in six months’ time. Here is the evolution of the futures market-implied fed funds rate for December 2023:

I think Robert Armstrong’s analysis is spot on here: “But it is wrong to characterise this as something happening. What it really is is something not happening, something that everyone thought was going to happen.”

For one, this highlights a recalibration in rates expectations that has not been manifested in other assets, at least not yet. For another, it just goes to prove the old adage, “It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

On a separate subject but in the similar vein of expectations, scuttlebutt is increasing that there will be new, higher capital requirements placed on banks. As Stimpyz points out on Twitter, “For those that thought the BTFP was a QE style bailout, here comes the 'pro-quo’”.

In other words, this is additional evidence of a new and different reaction function from the Fed. One aspect is it is more targeted than the blanket Quantitative Easing (QE). Another aspect is the expectation of a “payback” for any benefit provided, i.e. a quid pro quo. In sum, any benefit, emergency lending, “bailout”, whatever, that comes from the Fed should also be considered to come with a liability “to be named later”.

As a result, expectations about the Fed reaction function seem to be widely off the mark. There is a fair amount of evidence now that the Fed no longer plans on opening up the monetary spigots whenever trouble arises. Get used to it.

Economy

A new wave of mass migration has begun ($)

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/05/28/a-new-wave-of-mass-migration-has-begun

Last year 1.2m people moved to Britain—almost certainly the most ever. Net migration (ie, immigrants minus emigrants) to Australia is twice the rate before covid-19. Spain’s equivalent figure recently hit an all-time high. Nearly 1.4m people on net are expected to move to America this year, one-third more than before the pandemic. In 2022 net migration to Canada was more than double the previous record and in Germany it was even higher than during the “migration crisis” of 2015.

The main point the Economist makes is, “The rich world is in the middle of an immigration boom, with its foreign-born population rising faster than at any point in history”. This is meaningful because population growth is a key driver of economic growth (the other major factor being productivity).

Not only is this a striking change from “the rich world’s anti-immigrant turn of the late 2010s”, but it looks likely to continue, albeit at a more moderate pace. One reason is “More welcoming government policy” and another is that “migration today begets migration tomorrow, as new arrivals bring over children and partners”.

This is an unexpectedly pleasant surprise following several consecutive years of declining population growth in developed countries. Not only does this help ease a tight labor market, it also infuses greater dynamism into the economy as a disproportionate share of immigrants pursue entrepreneurial ventures. Good news all around; let’s hope it lasts.

Credit

A Much-Needed Crisis

One of the great quandaries of this investment landscape is determining whether inflation or deflation is most likely. John Mauldin asked exactly this question of William White, former chief economist at the Bank for International Settlements and veteran central banker at his recent Strategic Investment Conference. White explained:

“The private sector is deeply indebted. In the US, the households have come back a bit, which is good, but looking at it sort of globally, private sector debt has risen enormously. When you look at government debt, it's almost exactly the same thing. It's risen enormously. And in a way, this is how I think of it anyway, if we have real problems on the private sector debt side, that's going to drive us more into the deflationary outcome. If we have problems more on the government debt sustainability side and it's the government that's got control of the printing presses, then you're going to have more likelihood of an inflationary outcome.”

As a result, White assesses, “we may see both very high inflation and deflation as well”.

In one sense that appears to be equivocal and not very helpful, but it is actually deceptively useful. First, it establishes targets for where to watch for bigger problems: private debt in relation to public debt. Second, those will vary by industry and country. Third, a lot of possible combinations arise from that calculus.

Finally, while that still seems fairly innocuous, Paulo Macro articulates the implication: “It is the volatility of inflation and its path uncertainty that will eventually, inexorably raise term premia.” In other words, the lack of a clear direction and the potential for many different outcomes will have the effect of “raising term premia” - which raises longer-term interest rates. And that is bad for risk assets.

Geopolitics

Much of the talk of de-dollarization is centered on narratives that variously describe the US as declining in strength and status, and being untrustworthy. As the narrative goes, it a natural and sensible outcome that other countries might want to create alternatives to the increasingly unattractive US dollar (USD).

Janan Ganesh ($) poses an interesting alternative hypothesis - those other countries could just be wrong:

Second, these [emerging] countries have agency of their own. That includes the power to be wrong. At root here is the undying belief that, if something in the world is awry, the US and its allies must be culpable.

While there are certainly some elements of truth to the relative decline of the US, Ganesh’s insight helps explain the frequent overstatements. This is a function of being king of the mountain: Everyone is either gunning for you, envious of you, or both.

This poses an interesting possibility. What if the US government wants “de-dollarization”. It recognizes while USD once conferred great advantages, it has since become more of a burden - in the form of absorbing global trade surpluses and incurring unsustainable debts. As Michael Pettis explains ($), “The end of dollar dominance would be a good thing for the global economy, and especially for the US economy (albeit not, perhaps, for US geopolitical power)”. How would it go about changing things?

There are things it can, and arguably must, do unilaterally such as imposing controls on foreign capital flows. Virtually any move, however, is likely to be met with “an undying belief the US is culpable”. As a result, it would make sense to orchestrate conditions whereby foreign countries with large trade surpluses, like China, would want de-dollarization. Then, they would actually help with the effort. As Mr. Roarke always used to say, “Be careful what you wish for!”

I still believe the USD is highly unlikely to be challenged by another currency for global reserve status any time real soon. However, I also believe the US is increasingly aware of the disadvantages of such status and is working to change that in order to create a more sustainable monetary system. How it does so and exactly how long it takes I don’t have a good sense for, but I’m pretty sure it will done on terms favorable to the US.

Monetary policy

The Treasury’s Gambit ($)

https://concoda.substack.com/p/the-treasurys-gambit

There are several excellent points in this piece that details the developing construct for monetary policy. The latest development comes in the form of buybacks by the Treasury. So, in an important sense, monetary policy is expanding beyond the central bank.

Ostensibly, the effort is sensible in that it is designed to “boost liquidity in the secondary Treasury market”. This was a problem in March 2020 in the US and was a similar problem in the UK during the gilt crisis last fall. The idea is the “Treasury will become a ‘dealer of last resort’, acting as a buyer of illiquid bonds when no other participant is willing”. It’s not a perfect end solution, but it is a decent incremental improvement that can be enacted fairly quickly.

The “money” graphic (below) depicts the controls both the Fed and Treasury now have to fine tune financial conditions either tighter or looser as necessary. When the Fed and other market participants talk of the possibility of a “soft” landing, this is the dashboard in the cockpit to facilitate that end.

One observation is there is no mechanical link between the Fed and the Treasury on desired outcomes. On one hand, “if the Fed and Treasury have joint political goals, they can effectively bypass the Fed’s so-called independence, coordinating the easing and tightening of financial conditions”. On the other hand, if they don’t have joint goals, they can each work in opposition and neutralize the other’s efforts.

Another observation is, “The Treasury market provides those who oversee it the power to control global finance like never before”. That power could prove useful in overcoming a crisis. It could also be useful in steering inflation higher or lower. While the initial implementation of these tools may well be benevolent, however, “the golden age of intervention is yet to come”.

Fiscal policy

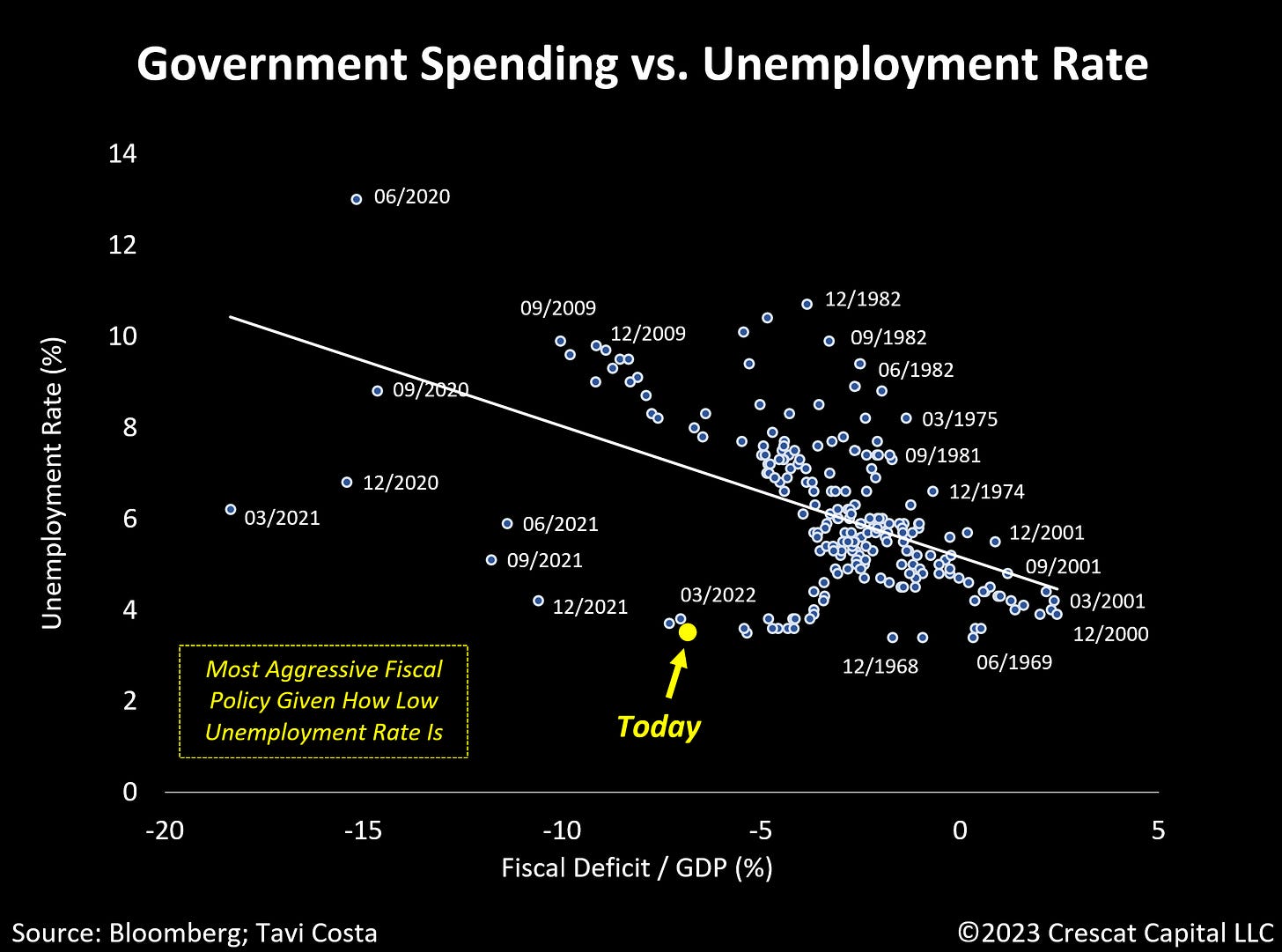

I really like this Twitter post by Tavi Costa because it highlights the role of fiscal spending on inflation which is often overlooked.

“The government is practically undoing the Fed's attempt to curb inflation. Throughout history, today we are experiencing the most aggressive fiscal policy given how low the unemployment rate is.”

At very least, this illustrates the importance of watching government spending in addition to monetary policy for clues on inflation. At most, it suggests government spending is actually driving the inflation train.

I suspect the truth is somewhere in between. Fiscal spending is a key driver for inflation while relatively tight monetary policy provides a lot of cover. Excessive fiscal spending can’t continue indefinitely so the main question is what eventually acts to constrain that spending?

Landscape I

Signs of Artificial Intelligence at Work

https://www.yesigiveafig.com/p/signs-of-artificial-intelligence

Now position yourself in 2023 where to a certain extent the opposite is happening. Equities rally while bonds are still pressured by Fed hikes (albeit moderately now that they are only 25bps and duration has fallen closer to 6.1). Equities up, the portfolio is overweight equities, sell equities, buy bonds. Rinse, repeat. With equities rising sharply into June while bonds have retreated on fears of a June hike, theory suggests an equity correction on the next rebalancing.

Another friendly reminder from Mike Green that market structure matters. When stocks go up, as they obviously have the last few months, and bonds are flat to down, which they have been, then balanced funds have no choice but to sell stocks. This has nothing to do with fundamentals; it is merely a function of the funds staying in “balance”. While there are clearly plenty of other factors involved, consider this a warning that not all signs point to yes (i.e., buy).

Landscape II

I have been noticing more and more happenings lately that don’t fit comfortably into any primary narrative scenario I consider. They just don’t feel right.

For starters, it seems like something is up in the State Department in regard to China. First, National Security Adviser, Jake Sullivan, who seems to be directing most policy for the Biden administration, met China’s top diplomat ($) in Vienna in May for “two days of ‘candid, substantive and constructive’ discussions”. And then CIA chief, Bill Burns, made a “secret trip to China to thaw relations” ($) that wasn’t reported until a month afterward. Then, out of nowhere, the Deputy Secretary of State, Wendy Sherman, retires, and a couple other members of the “China policy shop” will step down. As the Morning Dispatch hypothesizes ($), there may be “A U.S.-China Thaw in the Making”.

On one hand, it certainly appears as if there was a major change in direction. Harald Malmgren, a former State Department insider himself, tweeted: “Resignations at such a high level as Wendy Sherman's ‘Deputy Secretary of State’ normally involve couple of months notice giving time for nomination and Senate confirmation of successor. Sherman's resignation was effectively immediate, suggesting a very high level clash”.

On the other hand, China pro, George Magnus, doesn’t see any change in China’s disposition. He posted, “Patently not the case that China is seeking dialogue. Otherwise it would’ve responded to repeated US initiatives to do just that.” Weird dissonance and something to watch for sure. If there is a behind-the-scenes warming, it could upend a lot of market narratives.

On a very different front, weird things are also happening with employment numbers. These are even more important at present than usual since the Fed has repeatedly insisted that the labor market is a key driver of monetary policy. As long as the labor market remains “tight”, it will be hard for the Fed to ease up on financial conditions.

Lo and behold, however, different sources of data tell very different stories. Jobs numbers according to the widely publicized BLS surveys have been consistently outperforming economist expectations. After 14 consecutive “beats” now, the performance as been so consistent as to suggest systemic bias (h/t @SoberLook).

It turns out, there is another source of data that is far more accurate and, interestingly enough, far less frequently reported: Actual tax withholding numbers. Lee Adler reports ($) in his Liquidity Trader letter:

Withholding tax collections for the month through May 31 were indeed stronger than last year, and stronger than last month. But that’s in nominal terms only … On May 12, collections were running much weaker than on April 12. Payrolls were actually lower than the [sic] were the prior month.

Adler goes on to say, “this trend of surprisingly strong [BLS] jobs numbers in the face of weak withholding tax collections has gone on for months.”

How can this major discrepancy be reconciled? It’s possible the BLS numbers, which are lagging, subject to unpredictable business birth and death adjustments, and subject to substantial revisions after the initial report, are coincidentally painting a rosier picture than the withholding tax data.

Here’s a thought though. It’s also possible the BLS employment data were intentionally selected as a metric by which to gauge monetary policy - expressly for the same reasons. If the intent is to justify keeping rates higher for longer, the BLS employment data is almost a perfect selection to substantiate the policy. I think there is an excellent chance this is the case because it helps cushion the political pressure that might force the Fed to back off before it wants to.

In both of these cases, and others as well, the dissonant evidence suggests the possibility of events that are not currently seriously considered. The first suggests the possibility of detente with China and perhaps even some kind of peace deal between Russia and Ukraine. The second case suggests an effort to obfuscate a deteriorating employment environment. I don’t know what the probability of either of these happening is, but they are not zero.

Implications

With all of these questions about what the landscape is even telling us, it doesn’t help much to jump right into implications. Rather, let’s take a step back and try to make some sense of the convoluted landscape. For starters, it’s pretty clear intervention is increasingly the name of the game. As a result, it’s also pretty clear it is not anywhere close to a pure free market system any more.

A good next step, then, is to ask, “What do the powers-that-be want to happen?” The answer here also emerges partly in what it is not. For one, the pro-capital measures that got us into this mess are unlikely to get us out. Therefore, it is fair to deduce different, i.e., pro-labor policies will be more likely going forward. Another fair deduction is policies that sacrifice the long-term in order to just make it through to the next day will no longer be favored (or tolerated). Real solutions will have to be found and implemented.

Real solutions are almost assured of being painful, however, which means large amounts of political capital will be needed - which means people will need to fearful of the alternative. All of this leads to a severe downturn.

It’s not hard to imagine. The economy is already slowing down. Wages are falling behind inflation. Credit metrics are turning down. Bankruptcies are turning up. Commercial real estate is a disaster that is just starting to unfold. Shadow banks are still hanging on but will need roll over debt at much higher, and mostly uneconomic rates. Student loans need to be repaid again which depletes consumer spending power. Oh, and there is the potential for hotter conflict with China and/or Russia, disruption in Turkey, and several other geopolitical disturbances.

As I mentioned above, there are certainly other possible scenarios as well, but it looks like a pretty severe downturn is where things are most likely headed right now. That means lower inflation, or even deflation, in the short-term. Insofar as this is part of a plan to catalyze a big public policy (i.e., fiscal spending) response, it would also usher in a new era of inflationary pressures afterward.

In such an environment, the best investment lessons are general ones. In a time of extensive intervention by public authorities, it is very hard to have any kind of meaningful edge. That implies diversification. Given the potential for some very significant changes, it also suggests it will help a great deal to be ready to make big shifts as changes become clearer. Specifically, it won’t make sense to hold a lot of cash forever.

Finally, Charlie Munger’s advice is especially appropriate here: “Everyone is trying to be smart, I’m just trying NOT to be stupid”. In an environment where a lot of bad things can happen, it doesn’t make sense to stick your neck out too far. Yes, big changes will create big trading opportunities. But it will be treacherous for those who venture into areas they don’t understand well.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.