Observations by David Robertson, 7/21/23

Stocks have continued to roll even though earnings reports are revealing reasons to be cautious. Let’s see how long the “What, me worry?” ethos continues.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

This summary from @beatlesonbankin (from last week) pithily characterizes the market environment for the last couple of months:

SEC charges $COIN as illegal operation - stock doubles

Apple to report lowest q in 3 yrs - ath's

semis run rate rev down 20% - ath's

office towers empty - airports packed

1m tbills highest since Jan 2001 - the bubble lives !

it's a Costanza world! Do the opposite!

Per @Barchart via Twitter:

Call Open Interest in the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF $TLT is more than triple the OI for Puts signaling that options traders are betting that interest rates are primed to drop.

As @PauloMacro highlights in response, the view that inflation is over and it’s time to buy bonds is an extremely crowded view. If/when inflation creeps up again, look out!

On a related item, the US dollar (USD) has been weak since October and especially weak since early July - which has has provided a tailwind to risk assets. The following explanation was given by the FT:

Big investment banks are turning more bearish on the dollar as expectations grow that a “soft” economic landing will reduce the need for the US Federal Reserve to raise interest rates much further.

So, a “soft” economic landing combined with moderate rates and moderate inflation - aren’t those the conditions for a strong USD? Indeed they are. As a result, either the USD expectations are bunk or the economic assessment is bunk.

A third possibility is the decline reflects the bearish positioning itself more than anything else. When traders make bets, dealers need to hedge out those bets, which can create a self-fulfilling prophecy absent material flows from other sources. Market moves caused by this dynamic are usually transient and can reverse quickly. Either way, it’s just another day in these crazy markets.

Economy

Bridgewater warns US inflation fight is far from over ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/3489c43d-83ff-413b-9477-dd6c042211f2

Prince at Bridgewater, which manages $125bn, said markets were wrong to assume the Fed will soon ease monetary policy. “The Fed is not going to cut,” he told the Financial Times. “They are not going to do what is priced in.”

“Current levels of spending are being financed by income, not a credit expansion,” Prince said. “So inflation is really hard to bring down.”

The first point is a warning that markets are being too sanguine about the Fed imminently reducing rates. This is a position I agree with. I think such optimism is unwarranted because the economy is relatively strong and the economy is relatively strong because fiscal spending has been enormous. The conditions have changed, but investors’ relish of the “Fed put” has not.

This ties in to the second point. For at least twenty years now, when the economy slowed down, the Fed came in to ease financial conditions. In other words, growth was driven by growth in credit.

Things have changed since the pandemic, however. Now, fiscal spending is driving incomes higher. Higher incomes have translated to higher, and sustainably higher, consumer spending. As a result, even though credit conditions are getting tighter (and this will affect some people) overall income is sufficient to sustain healthy growth. In short, the economy is beginning to follow more of a business cycle than just a credit cycle. It’s going to feel very different.

China

China’s real estate nightmare continues apace though often outside the reach of mainstream media. Once again, Michael Pettis provides illuminating insights:

We shouldn't be surprised that measure after measure to stabilize and revive the property market has failed. In a highly speculative market, what drives buying is mainly expectations of continued price appreciation.

In that case [Beijing deciding to not re-inflate the real estate bubble] the best thing the regulators can do is decide what a much smaller property market with much lower prices will look like, what the associated losses are that must be absorbed, and the best way to get there quickly.

One of the important dynamics of a “highly speculative market” is that buyers buy solely with the expectation of prices continuing to go up. If the policy goal is to normalize the market, by definition prices cannot continue going up. As a result, there are no speculative buyers. This is the no-man’s land of failed price discovery.

From a top-down perspective normalization is actually pretty straightforward, if incredibly difficult, to implement. All you have to do is decide what sustainable prices will be and allocate the losses accordingly. Of course, this is far easier said than done.

For one, nobody wants to accept the losses. This is an easier problem to solve in an autocratic system like China’s, but it is still a non-trivial exercise complicated by lots of vested interests. For another, setting prices at a realistic, sustainable level will necessarily involve an entirely different type of buyer - and one who may need a little extra encouragement to take the leap.

Regardless of how things actually turn out, Pettis framework is a useful one by which to judge China’s progress in restructuring its property market. It also suggests the process will take quite a long time.

Emerging markets

With the S&P 500 getting stretched investors are looking for opportunities elsewhere and often land on emerging markets as an opportunity. Indeed, it is absolutely fair that some emerging markets have solid economic growth, good demographics, and very manageable debt burdens.

However, as I have mentioned in the past, emerging markets depend heavily on the status of the US dollar (USD). Any strength in USD creates headwinds. As a result, conditions have to be just right for emerging markets to benefit.

Increasingly too, as @SoberLook highlights in the graph below, emerging markets depend not just on the status of USD, but also on US demand. Some of this probably represents an effort by companies to migrate business out of China and into other countries that have better relations with the US and is therefore are more sustainable. Some of this also presents a risk of even greater reliance on the US though.

As emerging markets increasingly become a derivative of US business conditions, what point do they really serve in a diversified portfolio? That is a question asset allocators will need to be able to answer.

Politics

The American left and right loathe each other and agree on a lot ($)

The diagnoses from the new right and new left of what ails America are strikingly similar. Both sides agree that the old order that prized expertise, free markets and free trade—“neoliberalism”, usually invoked as a pejorative—was a rotten deal for America. Corporations were too immoral; elites too feckless; globalisation too costly; inequality too unchecked; the invisible hand too prone to error.

“It is a sign of a healthy politics that you have people with their eyes open on both sides of the political spectrum saying, ‘This is really broken,’” says Oren Cass, a former policy adviser to Mitt Romney and now the executive director of American Compass, a think-tank leading the charge on the right.

One of the interesting threads I have been following the last several weeks focuses on the areas where economic thinking of the right and the left is converging. I find the prospect of common ground especially curious given the intense cultural polarization between the two sides.

Nonetheless, there are areas of agreement which the Economist spells out nicely. Foremost among those is the notion that “neoliberalism” has been a bad deal for a lot of Americans. While the Economist notes, “Both the new left and the new right agree on empowering workers”, it also concedes the two sides still “disagree on the means”.

Disagreement on the means is no trivial disagreement and suggests policy could flip-flop as the political winds blow. However, the notion that there is agreement on a number of issues is a long way from the bitter partisanship of just a couple years ago.

Inflation

What Has Policy Tightening Accomplished So Far? ($)

https://theovershoot.co/p/what-has-policy-tightening-accomplished

The change in spending has been negligible compared to the slowdown in inflation, which suggests that improvements in the match between real production and demand have been more important than any shift in monetary policy.

While I think that the changes in policy were broadly appropriate, I am not convinced that they explain much of what we have observed so far. As I put it in a footnote in my previous note, “I do not see why the withdrawal of temporary measures imposed during an emergency should be considered economically significant compared to the end of the emergency itself.” The changes in monetary and fiscal policy so far have not been consistent with what would be required to force inflation out of the economy by squeezing incomes and spending. There has not been tightening so much as normalization.

Matt Klein makes a couple of really good points about inflation in this Substack post. The first is it appears most of the decline in inflation can be attributed to a better match in supply and demand relative to the imbalances caused by various supply constraints during the pandemic. As such, it appears monetary policy can take little credit for the decline in inflation experienced thus far.

A second point builds on the first. The monetary policy changes over the past year and a half only appear tight relative to the extraordinarily loose policy at the time. Relative to broader history, current monetary policy appears to be more of a normalization than a tightening.

What does this suggest for future inflation? Not much on its own. However, we do know a number of things that should be considered. For starters, monetary policy at its current setting isn’t doing much to throttle economic growth. Wages are continuing to rise. The narrative of inflation has been set which means everybody knows that everybody knows there is inflation. That includes consumers and corporate leaders (who set prices). Moreover, while many commodity prices have declined, supply is constrained and it wouldn’t take much to send them shooting up again.

On the other side of the equation, slowing economic growth will slow demand. Further, as overleveraged companies fail, money will get destroyed which will reduce liquidity.

So, there are several countervailing forces at work. Commodities and fiscal spending are the biggest wildcards. My vote is that one or both of these will tip the scales toward higher inflation.

Public policy

I have featured the thinking of Michael Pettis many times in Observations in regard to policy in China. This time he writes about policy in the US:

Rising US debt is indeed a problem, but the way to resolve it isn't by cutting back on government spending, and it certainly isn't by cutting back on government investment. The real way to resolve it is by reversing income inequality.

Income inequality reduces domestic demand by transferring income from high consumers (ordinary Americans) to low consumers (the rich). Supply-siders will argue that the reduction in consumption is balanced by a rise in investment funded by the higher savings of the rich.

But that isn't happening. American businesses aren't constrained by scarce savings so much as by scarce demand, so that more ex-ante savings does not lead to more investment.

This argument by Pettis is both simple and compelling. In the absence of a need for capital (by way of savings), the bigger problem for US companies is “scarce demand”. As a result, policies that reduce income inequality make things better for everybody by both increasing the size of the slices of the economic pie and by increasing the size of the pie itself.

While Pettis’ argument harkens back to a Depression-era kind of populism, it is much less a political statement than a template for effective public policy in a similar environment. After the “Roaring 20’s”, the pendulum had swung too far in favor of large corporations and banks. After Hoover’s failed policies in the early years of the Depression, FDR came in as President in 1932 and implemented a broad swath of policies that favored labor over capital.

It is especially interesting now that after a long period of capital being favored over labor (under the umbrella policy direction of neoliberalism), both major parties are working to curry favor with workers while distancing themselves from corporate interests. In short, neither the economics nor the politics of corporate power work well any more - so there is a good chance they will change.

Investment landscape

One of the points I have made many times over the last couple of years is the importance of liquidity in characterizing the investment landscape. On that front, central banks are usually the most important factors. In the US, the Fed’s Quantitative Tightening (QT) program has been reducing liquidity, but other factors, have been offsetting the impact.

One of those “other” factors is the Treasury General Account (TGA). While the run-down of the TGA earlier in the year (due to the debt ceiling), the recent refill of the TGA has not had a negative impact (yet) since it has been financed almost exclusively with T-bills and not longer-term bonds. Much of this extra T-bill issuance was absorbed by money market funds by drawing down funds held in the Fed’s reverse repo (RRP) facility.

A couple of important points can be taken away from all this. One is the large Treasury issuance did not create any threat to bank capital due to the funds held in the RRP. Concerns about this were overblown. Another point is the system has enough of a cash cushion that the huge Treasury issuance didn’t cause problems anywhere else either.

While these are important points to keep in mind, it is also important to be aware of two other points. One is that the cash cushion will not last forever. As deficits continue to grow, it is only a matter of time before excess liquidity gets soaked up. Another point is it is not in the Treasury’s best interest to do virtually all of its funding in short-term debt. Sooner or later, it will need to increase issuance of long-term Treasuries as well and when it does, prices are likely to fall and yields rise.

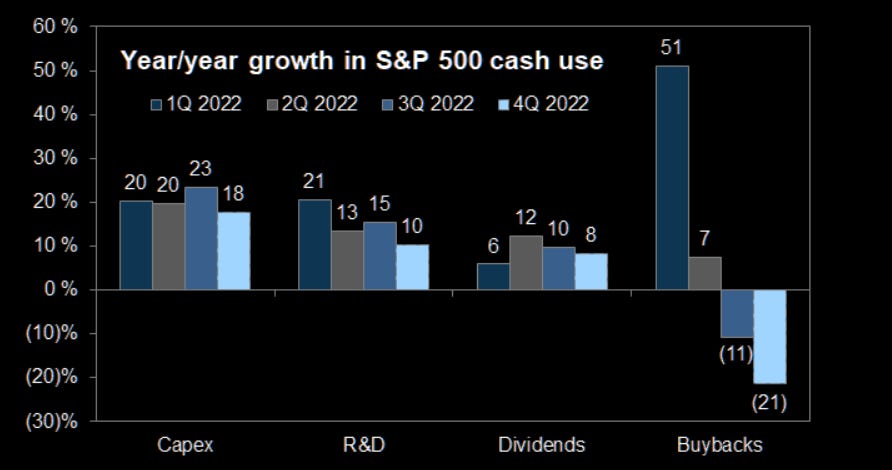

Finally, another big and persistent source of inflows into stocks has been through share repurchases. It has been extremely beneficial for companies to generate a constant bid for their shares through repurchase programs.

With borrowing rates higher now, however, it is no longer economical in many situations to borrow money for repurchases. Further, as many companies face pressure on revenues and margins, they just don’t have the same levels of free cash flow to apply to repurchases any longer. The graph below from themarketear.com reveals the steady decline buyback activity over the course of 2022. As pressure increases on corporate cash flows, so too will pressure increase on continued buybacks.

Implications

When the market is running as it has been, it can be difficult to maintain a defensive posture. This is so even when valuation measures are so excessive as to suggest negative returns over the next several years - as is the case currently. As Danielle DiMartino Booth put it recently, “Bubbles gotta bubble. It’s their nature.”

One of the things I always keep in mind is that if I don’t know why stocks are going up, I won’t know why they start going down either. More specifically, I won’t have any kind of reliable way of capturing the upside, but also avoiding the downside. For most long-term investors, it is best to avoid the temptation entirely.

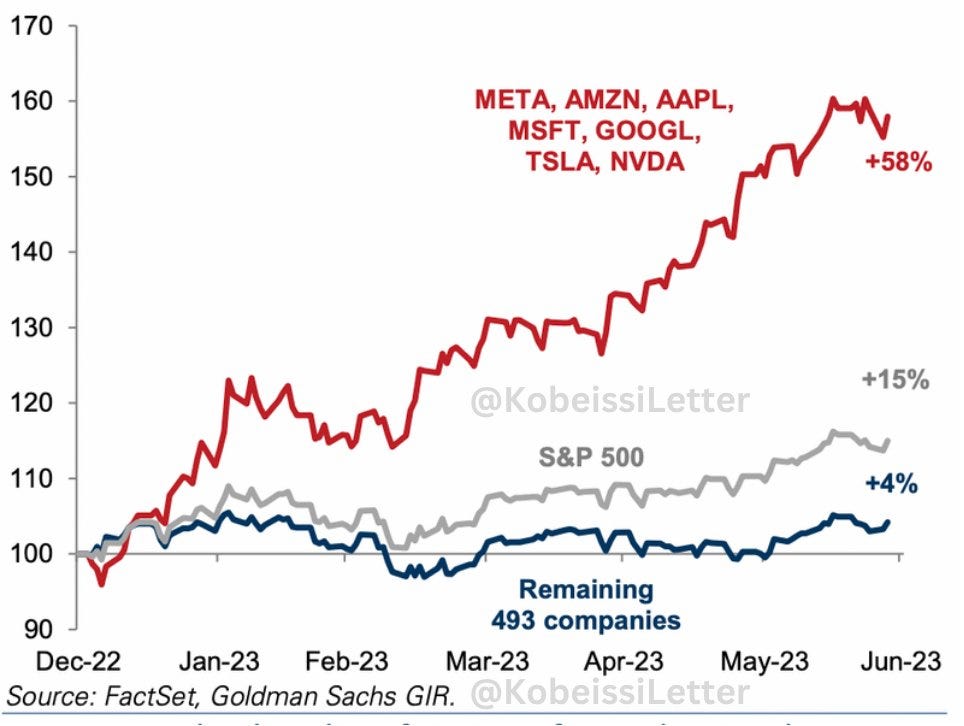

Another idea that can help one toe the line is to observe how little the S&P 500, absent the “Big 7”, has gone up this year. A graph posted by @KobeissiLetter illustrates the situation beautifully:

In other words, the vast majority of the S&P 500 this year is relatively flat, and therefore not something that is being missed out on. On the other hand, the Big 7 constitute a very leveraged bet on a small niche which is not normally the kind of bet a well-diversified, long-term investor would want to take.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.