Observations by David Robertson, 7/22/22

We’re in the lazy, hazy, crazy days of summer here and it looks like markets are taking on the same mindset - at least for the time being. As always, let me know if you have questions or comments at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

A rousing day for stocks on Tuesday highlighted what has turned out to be fairly strong performance over the last month. From the recent low on June 16, the S&P 500 climbed 8.1% (through 7/20/22). That puts the index above its 50-day moving average which sparks the interest of technical analysts.

Cryptocurrencies have also been making waves. Even as the fallout from a number of bankrupt companies continues to ripple through the industry, bettors have remained enthusiastic, pushing bitcoin up 11.5% over the same period (though falling precipitously Thursday).

The market has not responded much to earnings thus far, but it seems like that may have more to do with markets than earnings. A lot of chatter about positioning suggests most discretionary sellers have already done their selling, leaving little incremental pressure - at least until some new impetus comes along. This leaves markets vulnerable to violent upswings (like on Tuesday) despite fundamental underpinnings that appear fairly negative.

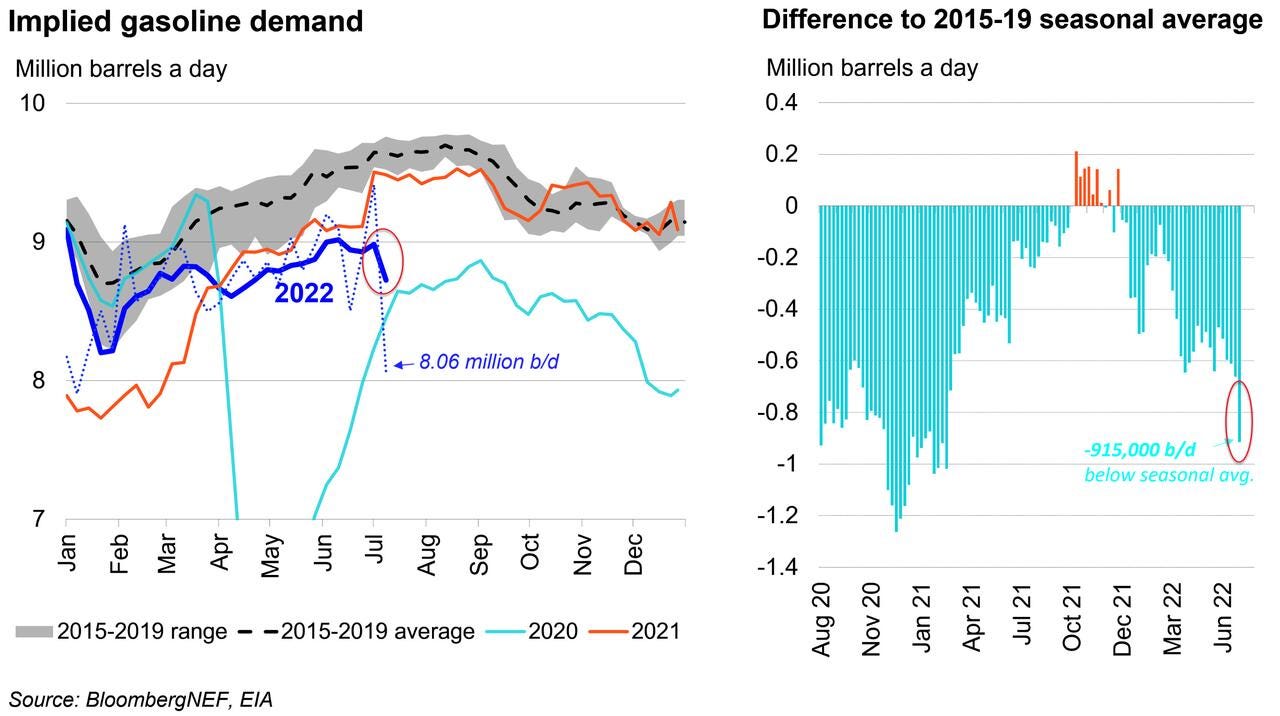

Finally, with a big hit to commodities already registered, we can now see some of the data that might have precipitated the move. These graphs from Zerohedge show pretty dramatically how quickly demand for gas is falling in this environment. With the latest weekly decline, demand has almost caught down to lockdown-impaired levels of 2020.

If these data are accurate it suggests the belief that oil demand is inelastic needs to be modified. Perhaps oil demand is more inelastic when consumers and investors have more faith that longer-term supply conditions can fairly quickly solve the problem of shorter-term high prices? If that is the case, high prices can do a lot more work on reducing demand than a lot of analysts are currently modeling.

Companies/earnings

A little blurb in the FT ($) about Baker Hughes (BKR), one of the three largest oilfield services providers globally, speaks volumes about the nature of investing in commodities-related businesses. In short, it’s hard and there are a lot more variables that need to go right than just the commodity price going up.

For example, despite the “benefits of surging demand in America’s shale fields”, BKR managed to lose money in the quarter - and to do so in a variety of ways. A large writedown due to the suspension of its Russian operations was a big part of the problem. However, the CEO also highlighted challenges including “component shortages” and “supply chain inflation”.

The main takeaway is that companies are complex “symphonies” of multiple groups doing different things. They are not just “exposures” to a certain macro factor, although that is the way many investors and advisors treat them. While commodity prices are usually a very important factor for the financial success of companies that produce commodities, they aren’t the only factor.

In other company news, AT&T got dinged on Thursday as its CEO warned “he expects higher bad debt and slower payments to continue” and consequently cut the year’s free cash flow forecast. Combined with the story of subscription declines at NFLX, a vague outline of the business environment is coming into focus.

For one, consumers are becoming financially “exhausted” and having to cut back on discretionary items like entertainment. The AT&T news demonstrates even essentials like phone service are now getting affected. While these items certainly speak to the status of economic growth, they also speak to a vulnerability of the subscription model that so many companies have striven to incorporate.

Credit

Capitulation watch! ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/ae189c04-8804-4641-85eb-6e8240493c50

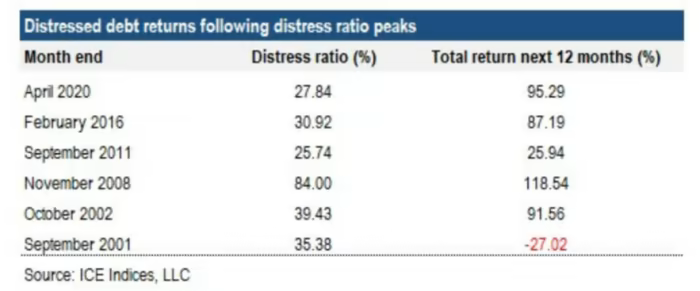

Another indication that investors have not quite quit on risk is provided by Marty Fridson of Lehmann Livian Fridson Advisors. He notes that high-yield corporate bond valuations are not particularly beaten down by the standard of past cycles. He points to the distress ratio, or the proportion of bonds that are trading at a yield spread over Treasuries of 1,000 basis points or more. The proportion of bonds trading that wide stood at 10.27 per cent as of last week. Here is what previous cyclical lows have looked like:

Great point here made by Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu at the FT. A lot of investors are looking for a “bottom” or some sign of capitulation to start buying again. Unfortunately, the credit distress experienced thus far doesn’t come anywhere close to past occasions of distress. In short, “We’re just not there yet”.

Politics

The God Gap Helps Explain a 'Seismic Shift' in American Politics ($)

https://frenchpress.thedispatch.com/p/the-most-important-religious-divide

As outlined in a New York Times/Siena College poll, “Democrats now have a bigger advantage with white college graduates than they do with nonwhite voters.” The Democratic Party’s losses with Hispanics are remarkable. Whereas Obama won 71 percent of the Hispanic vote in 2012, and Biden won 65 percent in 2020, now the Hispanic vote is “statistically tied.”

Of all ethnic groups, black Christians are the most likely to attend services, pray frequently and read the Bible regularly. They are also — here’s the kicker — most likely to believe that their faith is the place to look for answers to questions about right and wrong. And they are, by large margins, the most likely to believe that the Bible is the literally inerrant word of God. In short, if you find Christian traditionalism creepy, it’s black people you’re talking about.

David French has a great insight here that probably could not come from within, or anywhere near, the Democratic party. As he explains it, “The Democratic Party has a huge ‘God gap,’ and that God gap is driving a wedge between its white and nonwhite voters.”

A big part of that “God gap” is an almost total failure to understand religion and the role it plays in the lives of many people. Surveys of Hispanics and African Americans reveal people overwhelmingly identify more strongly with their religion than their political party.

This presents a huge problem for the Democrats. On one hand, Hispanics and African Americans have historically been important Democratic constituents. On the other, the party is increasingly being commandeered by college-educated whites whose views on religion, and politics and culture by association, are often very different. This means the driving ideology often fails to resonate with much of the party’s base.

With major battles brewing both within and across the two major parties, the stage is certainly set for some major turmoil. It will make for exciting (and consequential) drama.

Inflation

Inflation back at 2% "very optimistic" ($)

https://themarketear.com/premium

MS Rates Strategist, Guneet Dhungra, on why he thinks markets are being overly optimistic in pricing inflation getting to 2% by the middle of 2023:

1. "First, history suggests such a decline is extremely unlikely. Looking at the history of inflation over the last sixty years, a decline of the order of 7% in a year has never happened except for the Great Financial Crisis in 2007-2008. A similar but shallower decline of about 5.5% happened in 1975 and 1982 from starting levels of 12% and 11%, respectively.

2. Second, inflation is very broad based, which makes it less likely to come down as rapidly. Our biggest takeaway from May and June CPI is that the strength in CPI is very widespread. This is evident in how trimmed mean CPI has continued to increase in recent months, with May and June being the strongest 2 months so far."

I agree with both points here. The first is I agree the market does seem to be expecting a quick reversion to something like 2% inflation. The second is I agree a quick reversion is unlikely.

The points made by Dhungra are valid and add to an already substantive base of reasons for more persistent inflation. For one, shelter costs, which are the single largest component of CPI, are unlikely to decline much, if at all. For another, it is fair to expect wage growth to start outpacing overall inflation - because it will be a monster political problem if it doesn’t. Once that happens, it will be extremely hard for overall CPI to remain so modest.

Monetary policy

Liquidity Trader – Money Trends, Monday, July 18, 2022

https://liquiditytrader.com/index.php/2022/07/18/as-good-as-it-gets-before-the-end-of-time/

The picture [for Treasury supply] gets much tougher for the market from mid August through September. The TBAC told us that August 15 issuance will be $47 billion and that end of month issuance will be $61 billion. Then in September we’ll get hit with $67 billion at the mid month settlement, and $85.5 billion at the end of the month. That will coincide with the Fed doubling QT from $47.5 billion in system withdrawals to $95 billion.

With the Fed’s program of Quantitative Tightening (QT) underway now, it is especially important to understand what it means for markets. The first order effect is the market will need to absorb more Treasury supply since the Fed won’t be there pitching in. Further, the amount to be absorbed is going to increase substantially the next couple of months. With lower demand and greater supply there will be pressure for rates to go up.

That’s not the end of the story though. As Lee Adler tells us, since “The TBAC did not account for this QT in its estimate … The Treasury will almost certainly need to increase issuance in order to pay back its debt to the Fed for September”. This will have the effect of adding “to bond supply, while subtracting cash from the market”.

My take is long-term rates will need to go up in order to lure sufficient demand for Treasuries. This is what happens when a price-insensitive player like the Fed leaves the game. Insofar as this is correct, it will confound a lot of people who are focusing on short-term rate increases and recession indicators as the primary drivers. We will find out soon enough.

How higher interest rates will squeeze government budgets ($)

But measures of maturity can mislead. The WAM [weighted average maturity] can be skewed upwards by a small number of very long-dated bonds. Issuing 40-year debt instead of 20-year debt raises the WAM but does not change the speed with which rising interest rates affect budgets over the next few years. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), Britain’s fiscal watchdog, has suggested an alternative measure. Suppose you line up every pound (or dollar) a government has borrowed by the date on which the debt matures. Halfway along you would find the median maturity—the date by which half the government’s borrowing would need to be refinanced at higher rates. Call it the interest-rate half-life.

So, countries have been traipsing along, increasing debt, increasing deficits with nary a concern about the consequences. With rates going up, it is only a matter of time before higher interest payments will “squeeze government budgets”, and that time looks to be sooner than governments would like.

First, as the Economist rightly points out, WAM can be a deceptive measure of interest burden. Something like interest rate half-life is more accurate. But even that overstates the time governments have. The multi-trillion dollar increase in Fed reserves from QE is subject to floating rates. As those rates rise, so too will Fed profits flowing to Treasury decline.

With plenty of other causes pleading for government funds, the rise in interest costs is quite unlikely to go unnoticed. The Economist concludes, “Our calculations show that government budgets will feel a squeeze far more quickly than is commonly understood.” No wonder the Fed is enthusiastically diving into QT. Suddenly, debt is starting to matter again.

Investment landscape

Why markets really are less certain than they used to be ($)

But just how unusual is the turmoil? In order to quantify its uniqueness, Buttonwood has examined three measures of market-related uncertainty: expected asset-price volatility, divergence in economic forecasts and the unpredictability of economic policy as chronicled in the media. The tests suggest we really are living in unusual times.

An index built by Scott Baker of the Kellogg School of Management and colleagues tracks the frequency of articles that include worrying bundles of words—such as “regulatory”, “economic” and “uncertainty”—in global publications. It suggests that economic-policy unpredictability has been rising steadily since the financial crisis and is now far higher than in the late 1990s, when the index began.

I have mentioned the challenge of rising uncertainty many times but this article from the Economist provides even more evidence to validate the claim; this is not just some overly caffeinated worrying. So, one point is there are a variety of indicators suggesting uncertainty is increasing.

I strongly suspect people perceive a notion like “uncertainty” in widely different ways. For many people, it is an abstract concept that is hard to get one’s arms around. As a result, it doesn’t mean very much and it doesn’t incite action.

For a numbers person or a statistics person, the implications are clearer. Partly it means outcomes are more variable and therefore less likely to turn out well. Partly it means there is a much broader range of possible outcomes and therefore completely unimagined things might happen.

The net effect of greater uncertainty results in a significantly more challenging environment. To the untrained eye it comes across as a period of a lot of “bad” luck. Further, that bad luck can really take a toll. Sometimes clusters of “bad” luck or unforeseen events can lead one down a path from which it not possible to recover. Like bankruptcy, for example. The bottom line is uncertainty matters and can cause all kinds of problems for unprotected portfolios.

Implications for investment strategy

Given the strength of stocks, really over the last month, it is important to keep everything in perspective. While it may be tempting to take the favorable price action as some kind of signal that things are alright, or that monetary and/or fiscal policy are about to pivot and become more supportive, those prospects are more a function of hope than a conclusion based on evidence.

In order to better manage expectations, let’s take a step back for some perspective. For one, stocks are the riskiest layer of the capital structure. As a result, when business and financial conditions get tougher, stocks bear the brunt of the impact. For example, stocks are usually completely wiped out in the event of bankruptcy. Not for nothing, there is no shortage of global happenings that can cause serious problems.

Geopolitical challenges feature broadly. Russia continues its invasion of Ukraine which continues to effect commodities. Europe is reeling from the energy shortage it has caused. China is trying to manage through a restructuring of its massive real estate sector - and its methods of enforcing the peace are looking increasingly ominous…

In addition, demographics are getting worse almost everywhere. Excessive debt and dysfunctional politics are also widespread. In aggregate, it’s enough to make slowing economic growth in the US look almost trivial.

So, it’s important to manage expectations with stocks. It is unlikely there will be an “all-clear” signal any time soon. Rather, it is fairer to expect a long grind downward, punctuated by significant volatility. Amidst that backdrop, cash flow and currency will be key.

Thanks for reading this edition of Observations by David Robertson!

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.