Observations by David Robertson, 7/28/23

And the beat goes on. With the S&P 500 continuing an impressive trajectory since the end of May and the Dow Jones setting records for consecutive up days, one might think we’re in some kind of investment nirvana. That’s one interpretation, but I don’t think it’s the best one, at least not for long-term investors.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

One of the more notable characteristics of the market this year has been the striking decline in volatility. Indeed, volatility can be a self-fulfilling prophecy as vol-control funds increase exposure to stocks when volatility declines so as to maintain comparable overall volatility. This appears to have provided a tailwind for stocks all year.

Economy

The widespread adoption of AI by companies will take a while ($)

Yet for AI to truly diffuse through the economy , it needs to make its mark beyond the most go-getting companies. And this will take time. Although the internet began to be used by some companies in the early 1990s, it was not until the late 2000s that two-thirds of American businesses had a website. Some 70 firms in the S&P 500 still show no interest in AI, according to our analysis. And below the corporate crème de la crème, the trends look even less encouraging. According to one recent survey of American and Canadian firms, a third of small businesses have no firm plans to try generative-AI tools over the next year.

Your employer is (probably) unprepared for artificial intelligence ($)

And yet AI’s economic impact will be muted unless millions of firms beyond tech centres like Silicon Valley adopt it. That would mean far more than using the occasional chatbot. Instead, it would involve the full-scale reorganisation of businesses, as well as their in-house data. “The diffusion of technological improvements”, argues Nancy Stokey of the University of Chicago, “is arguably as critical as innovation for long-run growth.”

Yes, “The potential [of AI] is huge.” In the midst of all the hype though, here is a friendly PSA: Cool your jets a bit. It takes time for any new technology to become so widely adopted that it begins to affect broader economic numbers.

There are lots of reasons for this. Broadly, there are three separate types of obstacles for diffusion: “the nature of new technology, sluggish competition, and growing regulation”. In other words, more incremental and less revolutionary technology has less impact. Areas with low competition have little need for new technology. Regulation can also impinge upon adoption of new technologies.

Further, most people in the world are not nearly so gung-ho on new technologies as technophiles and early adopters. This can be for cultural reasons but, also very practical reasons. For example, the Economist also highlights:

Indeed, even the most powerful technologies take time to diffuse, because companies tend to use a hotch-potch of software and services, some of which may be years or even decades old. Replacing outdated systems can be costly, complicated and painful.

Finally, as I am reading The Fourth Turning is Here, by Neil Howe, yet another possibility presents itself as to why it may take technology longer than expected to diffuse. As Howe discusses, technology affects society, but society also affects technology. More specifically, the priorities of society at any point in time have a big impact on the ways in which technology is received and deployed.

Technological discoveries may themselves defy prediction. They are, in this sense, randomly exogenous, if you will. But how such discoveries are harnessed by the devices and infrastructures that change our lives is neither random nor exogenous. This depends critically on society’s priorities.

For example, a society with a large focus on individuality and choice could be expected to deploy a new technology like social media in a free-form way that emphasizes individual benefits. And that is what has happened.

Imagine if such a technology were introduced say, in an environment like World War II when societal goals and social cohesion were of utmost importance. It would be fair to expect significant government involvement, strict censorship, rigorous user authentication, and significant penalties for misuse. In other words, a totally different reception to, and impact from, the same technology.

The main point is, the impact of technology is not a function solely of the technology itself. It is also a function of the environment in which it is used. Probably a good point for analysts to keep in mind.

Credit

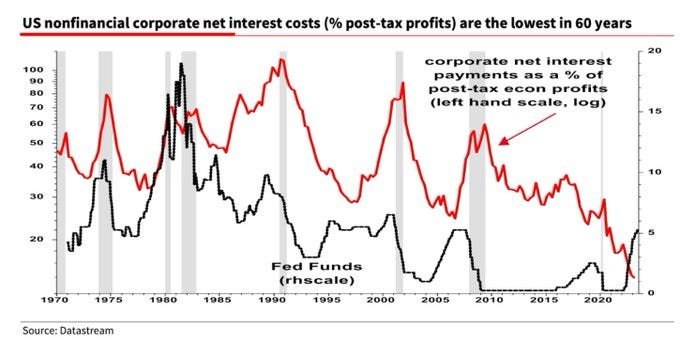

Albert Edwards posted this graph on Twitter which illustrates why much higher interest rates have thus far had so little effect on the economy. His answer is because a good chunk of companies loaded up on debt and extended maturities while rates were low. As a result, they were both insulated from the rate increases when they came and benefited from higher rates received on undeployed cash resources. Households have done this too.

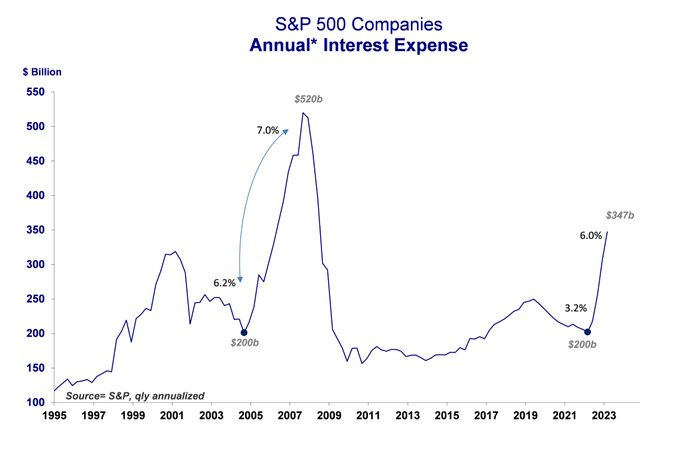

This is only one interpretation of the data, however. Stephanie Pomboy presents another, very different take. She points out the above data “come from the BEA's NIPA accounts [which comprises all companies]” By contrast, she posts the graph below of just S&P 500 companies. The difference is the top chart includes a large swath of small companies, companies that are “filing for bankruptcy at the fastest pace since 2009,” and therefore are not making interest payments. She concludes, “And it's emphatically NOT a good sign”.

It is absolutely true that bankruptcies are increasing, so Pomboy has a point. I seriously doubt that bankruptcies explain the entire difference between the two data sets though. The main lesson is to warn against forming a narrative too quickly about any set of economic data right now.

Banks

This graph from @SoberLook reveals a sharp decline in non-revolving debt.

Europe has been facing similar pressures. As John Authers reports, “publication of the European Central Bank’s lending survey (BLS) offered evidence of this [effects of tighter money]. Banks reported the sharpest quarter-on-quarter drop in demand for loans from companies on record, having expected a slight improvement.”

In the short-term, it is not surprising that bank lending would decline as rates increase by 500 bps in a little over a year. This is important because commercial banks are the primary source of money supply growth. If loans are declining, then money supply is going down. Obviously, this will crimp inflationary pressures.

It is important to also keep the big picture perspective in mind, however. In the US in particular, government policy is focused on regaining control of the financial system from unregulated, nonbank lenders. Part of the price to pay in doing so is higher short-term rates. While these higher rates also impede bank lending in the short-term, they are part of a bigger plan.

Once the unregulated nonbank lenders are mostly cleansed from the system, not only will banks have access to a larger universe of borrowers, but are also quite likely to have support for government-sponsored priorities such as industrial policy initiatives, among others. As a result, this will be an important space to watch for cues as to the trajectory of money supply, and therefore inflation.

China

USD/China - The Donkey Kong Dollar Peg. ($)

https://www.urbankaoboy.com/p/re-usdchina-the-donkey-kong-dollar

I believe that China needs a weaker CNY but fears losing control of the situation and is desperately trying to manage the optics against a Disorderly Devaluation; similarly, the raison d’etre for the HKD Hard Peg no longer exists, but the PBOC/HKMA fear the repercussions of breaking the peg.

The Chinese yuan (CNY) has been in the spotlight for several years. Between its aging demographics, debt-laden real estate sector, and export-reliant economic model, investors have repeatedly tried to guess when it will all fall down and result in a massively weaker currency. Michael Kao argues the time is nigh.

Of course, there are a million moving parts and of course, China has a great deal of control over when it happens, and perhaps even if it happens. The main points are that a CNY devaluation is an active risk and if/when it happens, it will send a gale-forced deflationary wind through global capital markets.

Eurozone

On the topic of currencies, the Euro has been performing extremely well as John Authers highlighted earlier this week.

Surely, this explains at least part of the recent weakness in the US dollar (USD). The conundrum, however, is why is this the case? As the US economy clips along at a decent pace, all evidence points to Europe’s falling fast. Germany, its biggest economy is dropping like a rock according to this graph from @SoberLook:

Factory output has witnessed its most rapid contraction in over three years while new orders continue to shrink, and for the first time since January 2021, payroll numbers have also seen a decline. In addition, manufacturing purchase prices are dropping at one of the most accelerated rates in the series' history.

And the German Dax? It has surged by 22.55% over the last 12 months, illustrating that market flows only sometimes mirror economic realities.

Partly this looks like a hugely overbought Euro and a hugely oversold USD. Partly it looks like just another case of market insanity.

Monetary policy

The Federal Open Market Committee met on Wednesday and raised rates 25 bps as was expected. Both the press release and Fed Chair Powell’s comments in the press conference were as featureless and anodyne as ever. The main message of both form and function: There’s nothing to see here.

Despite the bland serving of Fed speak, a couple of messages can probably be deduced. For one, since Quantitative Tightening (QT) was kept unchanged and very much in the background, it is fair to assume the Fed doesn’t want to increase the program. This would have been a good time if it did. For another, if the Fed was uncomfortable with the strong market - and its countervailing effects on monetary policy - this would have been a good time to say so. It did not.

As a result, it is probably also fair to say there is unlikely to be any kind of big statement to be delivered at Jackson Hole in August. I have heard scuttlebutt to that effect, but if that were the case, there should have been some kind of stage-setting at the meeting on Wednesday. There was not.

In short, it is looking like the Fed considers its job to be holding short-term rates about where they are, continuing QT at its current pace, and staying in that mode for as long as possible.

In addition, as I have read through various takes on the FOMC meeting, it really is an ink blot test; it’s amazing how many different interpretations stem from the exact same source and same verbiage. Part of this is an “eye of the beholder” phenomenon. Part, however, is reading between the lines.

For what it’s worth, Powell’s dismissal of stock market performance as a factor in monetary policy, his strictly theoretical definition of appropriately restrictive policy, and his recent attribution of soaring interest payments (as a portion of the federal budget) as fiscal issue, suggest two important things to me.

First, he is positioning the Fed to take a smaller role in overall policy. No longer is it of the ilk of “Omnipotent Central Bank” that will do “whatever it takes”. Now it is reverting to its more traditional and more technocratic role. Relatedly, Powell’s comments also suggest a sensitivity to not being the “fall guy” when markets turn south. I do believe he is politically savvy enough to know when that happens, the blame game will be ruthless.

Investment landscape

Air Pockets, Free Falls, and More Cowbell

https://www.hussmanfunds.com/comment/mc230724/

You’ll notice that none of the foregoing discussion is focused on recession probabilities, employment, inflation, or earnings expectations. The reason is that the consequences of steep overvaluation, unfavorable internals, and extreme overextension seem to be largely indifferent to these considerations. There’s often no identifiable “catalyst” associated with various market peaks, air pockets, and free-falls. Catalysts tend to emerge later, if at all. To some extent, the initial losses are more behavioral than economic – extreme overextension simply tends to become exhausted, followed by concerted attempts by speculators to exit at still-elevated levels.

While there is little that is new in this analysis by John Hussman, it is timely and also provides a useful reminder about markets that exhibit the kind of “steep overvaluation, unfavorable internals, and extreme overextension” that the market exhibits today.

Foremost among these is that economic criteria no longer matter in identifying the trajectory of the market. When commentators (myself included) say the market has become detached from fundamentals, this is what is meant. It does not matter what the economic data say, the market is moving due to other, noneconomic forces.

What are these other, noneconomic forces? Mainly they are behavioral. As such, there isn’t necessarily any good reason why stocks continue to go up. By the same measure, however, there isn’t necessarily any good reason either when the start to go down. This makes trading these situations virtually impossible.

Investment landscape II

Andy Constan posted this “script” to describe what is required of monetary policy to achieve the goal of subduing inflation:

The Script “The only way to kill inflation.”

Act 1. Higherer for Longerer Island - Hikes continue and don’t achieve goal.

Act 2. Long end yields rise to new highs – Requires a supply catalyst.

Act 3. Multiple compression – Higher yields take the legs out of equity rally.

Act 4. Earnings contraction – The tightening of Act 2 and Act 3 hit demand.

Act 5. Recession Island – Finally. as equities sell off, companies fire workers.

I find Constan’s outline to be useful for a number of reasons. A big one is it provides very clear explanations for each step of the process. This makes it easy to test and validate the rationale. It also makes it easy to compare to other “scripts”. In particular, it provides an instructive comparison to the hypothetical three-plank monetary policy platform I outlined in the market review I posted two weeks ago.

By and large, there is a great deal of agreement between my outline and Constan’s. We both see inflation continuing to be a problem. We both think the Fed will need to do more in order to contain inflation. We both see long-term rates eventually going up and hurting stock prices in the process. The main area of difference is I view monetary policy as being mostly consistent with, but ultimately subordinate to government policy. Constan seems to view government policy as mostly distinct from, and immaterial to, monetary policy.

That said, Constan illuminates a couple of issues I have been struggling to get my arms around. For example, I have been surprised that the rate hikes implemented thus far have not had more of a negative effect. As Constan explains, this is partly due to a resilient market: “Asset prices have remained buoyant and that has both provided increased wealth for consumers to tap and emboldened corporations to hoard workers instead of cutting payrolls.” Good point: Payroll changes are more a function now of stock price than P&L.

Another problem with the transmission of monetary policy has been due to Treasury’s decision to increase funding with bills rather than bonds: “In absence of bond supply there is no reason for bonds to trade lower in price.” As he highlights, “Act 1 will only end when supply of long-term treasuries reappears and pushes long term bond yields higher in both an absolute yield and term premium sense.” This is completely consistent with my statement: “it is important at some stage to allow long-term rates to rise above short-term rates.”

This is where there is an important nuance in our views. Constan says simply that the eventual increase in long end yields “Requires a supply catalyst”. More specifically, Treasury will need to increase the funding composition of bonds. This could be announced as soon as late July/early August.

I completely agree with the notion of a supply catalyst (which I have been reporting), but believe that catalyst will be a very deliberate part of government policy. I think the Biden administration (any administration for that matter) would prefer to have a market downturn this fall so that it can boost markets in front of the presidential election next year. Politically, it is far too risky to chance a big downturn during an election.

We’ll see. My political economy interpretation leaves a lot of wiggle room for implementation, but it does suggest we’ll be moving into Act 2 before long. Regardless, I view the bond supply decision as a major government policy decision. As a result, when and how this plays out will reflect on political priorities.

Implications

One possible interpretation of recent market gains, and a somewhat counterintuitive one, is that such gains make difficult policy decisions easier. By this argument, both Fed Chair Powell and Secretary Yellen know higher rates are biting and know once Treasury increases bond issuance, long-term yields will go up. They also both know China, Japan are struggling with their own problems that could cause money to flow out of Treasuries. Why wouldn’t they want the biggest cushion (i.e., strongest markets) to soften the upcoming probable, though unpredictable, pressures on the Treasury market?

If this view is correct, it means the interpretation by many investors that recent gains suggest an increasingly hospitable market environment are not only wrong, but dangerously wrong.

Part of the reason, as Hussman explains, is since no particular rationale or catalyst is needed for an “air pocket” or “free fall” to begin, there is no reliable way to avoid such setbacks. What this really means is the gains in these types of sequences are ephemeral. They may appear super-tempting to get in on, but they are virtually impossible to get out of with a profit. As a result, it is normally best for long-term investors to either ignore these events entirely or to just watch them for entertainment.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.