Observations by David Robertson, 8/2/24

The “slow” summer months continue to be inundated with news. Let’s jump right in.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

Market sentiment was captured beautifully by a trio of company observations. O-I Glass reported Tuesday after the close and lowered guidance for the year. The stock dropped as much as 16% after hours. By 11:30 Wednesday morning, it was up 9%.

Microsoft also reported Tuesday after the close and showed generally good results with the exception of a slight miss in its cloud business. After hours it was down as much as 6%. By Wednesday morning, it was only down 1%.

Nvidia closed Tuesday on another down note after a long week of declines. Wednesday morning it was up nearly 12% on no company-specific news.

One common theme in all of these is the Fed: The possibility of a Fed rate cut in September became even more palpable on Wednesday with the FOMC meeting. Another factor may have been some buy-the-dip mentality as a reaction to the rugged last two weeks of July. Regardless, by midday Wednesday, the S&P 500 was up 1.7%. There was much rejoicing.

Until Thursday morning anyway. Economic numbers came in weak and the S&P 500 gave back almost everything it gained the day before. More weak numbers and more selling came Friday morning. The most notable feature was that bad news became bad news again as sentiment clearly shifted to concerns about recession.

In other news, HFI Research posted (h/t @PauloMacro), “US oil production has leveled off once again coming in at ~13.122 million b/d for the last 4-weeks. It will be very difficult for the Permian to keep US oil production around ~13.3 million b/d.”

This is potentially an extremely important milestone for oil prices. Not only has most of global supply growth come from the Permian in the US, but the increasing weight of that supply has shifted pricing power away from OPEC. If this is the plateau of Permian production, and it certainly looks like it could be, pricing power shifts back to OPEC and that points to higher oil and gas prices.

Axios posted an interesting tidbit on China’s artificial intelligence (AI) effort. Apparently, “speed bumps” are getting hit due to “the Chinese government’s need to to control political speech.” It’s regulator, Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), “requires companies to prepare between 20,000 and 70,000 questions designed to test whether the models produce safe answers”. That sounds like a pretty significant handicap for producing AI models.

Geopolitics

While investors were busy regaling the delights of potential future rate cuts by the Fed, the following headline was emblazoned across the front page of the FT: “Iran vows revenge on Israel for killing of Hamas political leader in Tehran”.

In a separate story, the FT ($) reported:

“This is not only a massive blow to Pezeshkian [Iran’s new president] but a far bigger blow to the Islamic republic, which is now literally being challenged by Israel to go to a war,” said Saeed Laylaz, a reformist analyst. “Israel’s main message to Iran is, ‘We could kill any of Iran’s leaders too’.”

Yet another FT ($) story assessed:

US-led efforts to end the war in Gaza have floundered and been dealt a severe blow by the death of Haniyeh, the main Hamas interlocutor with mediators. Instead, the US and the region is grappling with day-to-day management of a crisis that is becoming ever more complex and deadly.

One point is this is a conflict that refuses to settle down or go away. Another point is the US is at significant risk of getting sucked into it.

Technology

Software is the new Hardware

https://www.thediff.co/archive/software-is-the-new-hardware

If you spend much time trying to make the case for deep tech investments, you start to get a real appreciation for what a great business software companies have. There are nominally high fixed costs, but most of those costs become fixed well after the company is established. Meanwhile, the marginal cost of delivering the product rounds down to zero, and that means that companies have enormous flexibility in how low they can price

All of that is changing. The marginal cost of writing code is dropping, while the marginal cost of running it—to the extent that much of this new code is frequently using inference, or doing other computationally-intensive tasks—is rising. That's the reverse of the economic tailwind that's done so much for software engineers' incomes and software investors' returns.

What does require that headcount is making sure that the product is integrated with any of X CRMs, automatically archived in Y storage providers, integrated with Z business communications tools. The biggest product typically has the most integrations, and as the cost of launching a new SaaS product declines, the investment required to have the right integrations for 99% of customer use cases actually increases.

As Byrne Hobart rightly describes, the software business has historically had a very attractive business model. High fixed costs but low variable costs mean that once critical mass is established, the business has enormous flexibility to trade off high margins for greater revenue growth.

As he also describes, however, those days are coming to an end. While the model still largely applies to basic functionality, the increasing complexity of the IT landscape means it takes a lot of extra and ongoing work to make any program work nicely with any given customer’s particular array of hardware and software. Further, the cost of running programs is going up as computational complexity increases. As a result, the economics of software is gradually regressing to that of hardware.

In one sense, this may not matter a whole lot because the importance of network effects has become an even more important driver of valuations. That said, tech sector valuations are stretched and any headwind could trigger a reset.

China

Why is Xi Jinping building secret commodity stockpiles? ($)

Last year China’s imports of many basic resources broke records, and imports of all types of commodities surged by 16% in volume terms. They are still rising, up by 6% in the first five months of this year. Given the country’s economic struggles, that does not reflect growing consumption. Instead, China appears to be stockpiling materials at a rapid pace—and at a time when commodities are expensive.

Although it is the world’s refining centre for many metals, it imports much of the raw material required, ranging from 70% of the bauxite it uses to 97% of cobalt. China keeps the lights on only with imported energy. It has a lot of coal, but its deposits of other fuels do not match its needs, forcing it to bring in 40% of its natural gas and 70% of its crude oil. China’s dependence is most acute for food.

While the stockpiling of important commodities by China has been going on for many years, the process has accelerated as of late. For a country considerably short of a wide variety of critical commodities like food and energy, it’s certainly sensible to have buffer stock. The recent rate of increase, however, begs another possible motive: Perhaps the country is preparing for geopolitical conflict. Perhaps it is preparing to take over Taiwan.

Certainly these rank as valid possible motives and need to be seriously considered. They are not the only other possible motives, however. For example, it is possible China is taking a page out of President Biden’s playbook with oil. When you have a large backup supply of a major commodity, like oil in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, you have the ability to at least temporarily affect prices by releasing or adding significant volumes. That can come in handy.

Not only does it grant a fair amount of power to lower prices if desired, as Biden did when he released oil reserves in order to lower gas prices, but also to raise them by withholding important incremental supply. Combined with China’s “increasing caginess” by way of canceling the release of data on many commodity inventories, it is becoming harder than ever to gauge global demand accurately. Increasingly, commodity prices are a function of geopolitics as well as supply and demand economics.

Public policy

Global trade imbalances have always had political implications but have been of particular interest to Donald Trump. There is no doubt that persistent American trade deficits sounds like a problem to be fixed, and there is some truth to it. Importantly, however, it’s not the whole truth. The bigger issue is that persistent deficits are only a symptom of a deeper and more fundamental problem. No one explains this better than Michael Pettis.

Part of the problem with economic analysis in general is that it relies on assumptions that too often do not hold in the real world. For example, floating exchange rates have the potential to facilitate fluid adjustment to changing economic conditions. However, as Pettis explains, “in a highly distorted trade environment driven by beggar-thy-neighbor policies, their [floating exchange rates’] main function may be to accommodate persistent trade and capital imbalances”.

This highlights one of the problems. In the real world, some countries do engage in beggar-thy-neighbor trade policies (e.g., China, Germany). In short, as Pettis describes, “countries exploit global integration to externalize domestic unemployment and debt creation.” As a result, floating exchange rates merely propagate the deficient demand problems in those countries to other countries. The core problem is deficient demand in countries like China and Germany. Solve that and you solve the trade problem.

If you don’t solve it, you have a different problem. As Pettis also explains, “There are broadly three ways the US can adjust to excessively high ex-ante savings: unemployment can rise or, to prevent it from rising, either the Fed can encourage household debt to rise or Washington can expand the fiscal deficit.” This reveals the fiscal deficit problem largely as a function of beggar-thy-neighbor trade policies.

This has two important implications. One is, “The rising US fiscal deficit … is not a freely-chosen policy.” Indeed, Pettis goes even further, “In a hyper-globalized world, a country that does not control its capital and trade accounts cannot avoid the impact of aggressive trade and industrial policies.” Trying to cut spending does not solve the problem.

This leads to another, even broader implication: “democracy, national sovereignty and global economic integration are mutually incompatible.” Therefore, if the US is unwilling to concede democracy or national sovereignty, the only way to left to sustainably manage trade imbalances is by limiting economic integration by way of controlling capital and trade accounts.

The downside of this is it exposes adamant globalists and tariff advocates alike as being misguided in trying to solve the problems of trade imbalances and persistently increasing debt. The upside is that both of these issues get resolved naturally when the bigger problem of deficient demand is properly diagnosed and treated. The only hitch is it is bound to cause friction with the countries like China which have benefited most from a playing field tilted in its favor.

Monetary policy

While most normal people are enjoying summer activities and watching the Olympics, finance nerds have been basking in monetary festivities of their own. The Bank of Japan (BOJ) raised rates a tad and pared its bond buying program back. The Bank of England (BOE) lowered rates by a quarter point.

The real show was on Wednesday, however, when bulls of all types bid up stocks before the open simply in anticipation of good news from the Fed. The press release revealed nothing new, although it did sport a more dovish tone than the last report.

As Bob Elliott posted in a nice thread: “Markets are taking at face value that the Fed, ECB, BoJ, and BoE will aggressively pursue shifts toward ‘normal’ ahead, but the data that drives these moves suggests caution … The result is those betting on swift transitions to normal will likely be disappointed ahead.”

Further, in what is increasingly intertwined with monetary policy, the Treasury’s Quarterly Refunding Announcement (QRA) came out this week. This event was more anticipated than usual because unusually high issuance of Treasury bills has provided a huge amount of liquidity that has offset the Fed’s attempts to quash inflation.

Alas, there was no big change to report. Treasury still “does not anticipate needing to increase nominal coupon or FRN auction sizes for at least the next several quarters,” although it did concede to “incremental increases to TIPS auction sizes in order to maintain a stable share of TIPS as a percentage of total marketable debt outstanding.” As a result, the QRA disproved the more extreme forecasts that Treasury would flood the market with liquidity ahead of the election.

There were a few clues, however, as to how Treasury issuance may unfold in the future. The recognition that “T-bill issuance should continue to act as a shock absorber” which sometimes necessitates “operating with a T-bill share as high as 30-35% for short periods” provides an outline for how far bill share could go. Short answer, quite a bit higher.

In addition, the issue of demand for Treasuries was also addressed. While rightly identifying the increasingly prominent role of price-sensitive buyers such as hedge funds and households, the report stated demand from such sources “could remain robust as inflation eases, improving the value of Treasuries as a hedge for risk assets.”

This sounds like a “wing and prayer” outlook for Treasury demand. Not only is the assessment equivocal at best, it depends on forecasts for lower inflation and bonds serving as a good hedge. Neither of these is certain or arguably, even very likely. A more honest assessment would read something like, “Since demand for bonds is increasingly determined by price-sensitive buyers, it is increasingly likely that lower prices/higher yields will be necessary to provide sufficient demand.”

Of course, significantly higher yields, say greater than five percent on the 10-year Treasury, scare the crap out of Treasury officials just a few months before an important election. The reason is that long-term rates are more important for determining financial conditions right now that short-term rates. When those go up and stay up, the economy will slow down noticeably.

So, with the supply of Treasuries continuing to increase, demand being price sensitive, and the room running out for excess bill issuance to provide a cushion, it’s only a matter of time before long-term yields go up. Fortunately, the QRA also highlighted the conditions under which that might happen with a ready-made excuse: “lack of resolution of the debt ceiling runs the risk of undermining the foundation of the U.S Treasury market.”

Investment landscape I

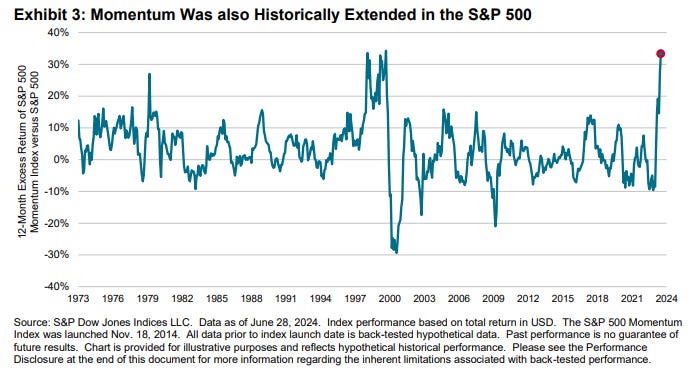

Anyone who has even remotely been following the market knows momentum has been a huge factor this year. In a note earlier this week, John Authers provided some useful perspective on this phenomenon.

First, as he points out, “It’s a phenomenon of market behavior, not fundamentals.” Second, the outperformance of momentum this year has been at historical levels: “momentum’s outperformance of late has exceeded anything in the last 50 years, barring the very top of the dot-com bubble before it burst in 2000”:

As exceptional as that seems, and it is, it is even more so when put in the context of longer-term history. Interestingly, and probably counterintuitively to some, “the equal-weighted index outperforms over the long term.” Indeed, it not only outperforms, but massively outperforms:

This tells us two things. First, the recent outperformance of momentum is quite unusual in the context of history. Second, it is extremely unlikely to persist. Over time, the equal weight index wins out. Investors can either learn this the easy way or the hard way.

Investment landscape II

Stocks ended July looking pretty shaky and investors attributed that to any number of causes including slowing economic growth and heightened political uncertainty, among others. While those factors almost certainly contributed, Bob Elliott suggested an even better reason for the volatility:

Stocks in the US today don't have a growth problem, they have an *expectations problem*. Not only are forward earnings expected to grow at an extraordinary pace for a late cycle economy, but PEs on those forward expectations are near all-time highs.

This is a great point. It’s not that companies aren’t growing or aren’t performing well. It’s that they are having trouble meeting extremely high expectations that include rising margins and accelerating growth.

He concludes, “The stock market is priced to perfection, and so far this quarter is providing plenty of data points that the perfection is unlikely to be achieved in reality.” Buyer beware.

Implications

The strong rebound in stocks on Wednesday on basically no news except the Fed meeting suggests some important characteristics of today’s markets. The fervor for stocks is not driven so much by financial performance or “irrational exuberance”. Rather, it seems to be driven by a combination of structurally beneficial flows and the acclimation to monetary policy that has consistently favored strong stock returns.

Even with a major selloff in 2022 caused by rising rates, the belief in the Fed to dictate market direction has remained firm. After all, the belief goes, that was only a temporary setback to get back to “normal”.

What that belief system does not yet seem to incorporate is the increasing potential that those halcyon days of favorable monetary policy may be gone forever. It also does not yet incorporate the possibility that mechanical flows into stocks will eventually plateau and even reverse. Indeed, it doesn’t seem to incorporate much thinking at all.

For those who do think and try to plan ahead, this presents great opportunity. There will be opportunity to avoid the pain when rabid expectations are not met. There will also be plenty of opportunities to acquire risks assets on sale. It will take time, and will likely be a very bumpy and irregular process. But it is possible to chart a course that avoids many of the biggest pitfalls.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.