Observations by David Robertson, 8/25/23

It was another quiet, end of summer week. As a result, I will spend a little more time reflecting than reporting on news.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

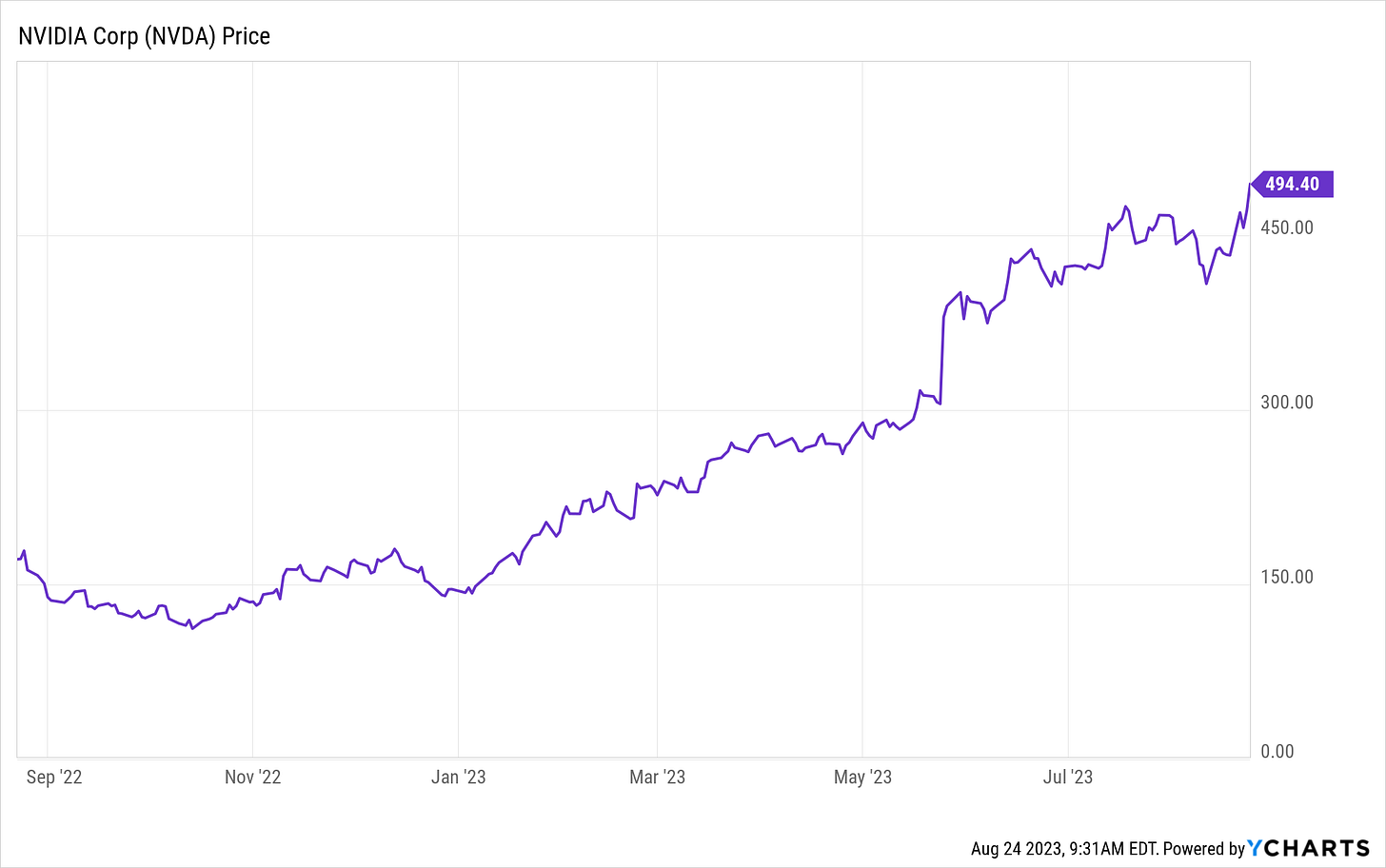

The star this week was NVDA, which has been the poster child of the artificial intelligence revolution. It reported blowout earnings on Wednesday and the exuberance has been reflected in the stock.

Whether that exuberance is irrational or not is to be determined. Certainly short-term results are good, but the sustainability of those results are in question as demand was almost certainly pulled forward to avoid sanctions placed on Chinese purchases. Geopolitical risk looms as an ongoing threat.

None of that matters now, of course, but it will. In addition, it’s good to keep in mind that NVDA has been a huge force driving the S&P 500 up this year, and can be just as big a force on the way down.

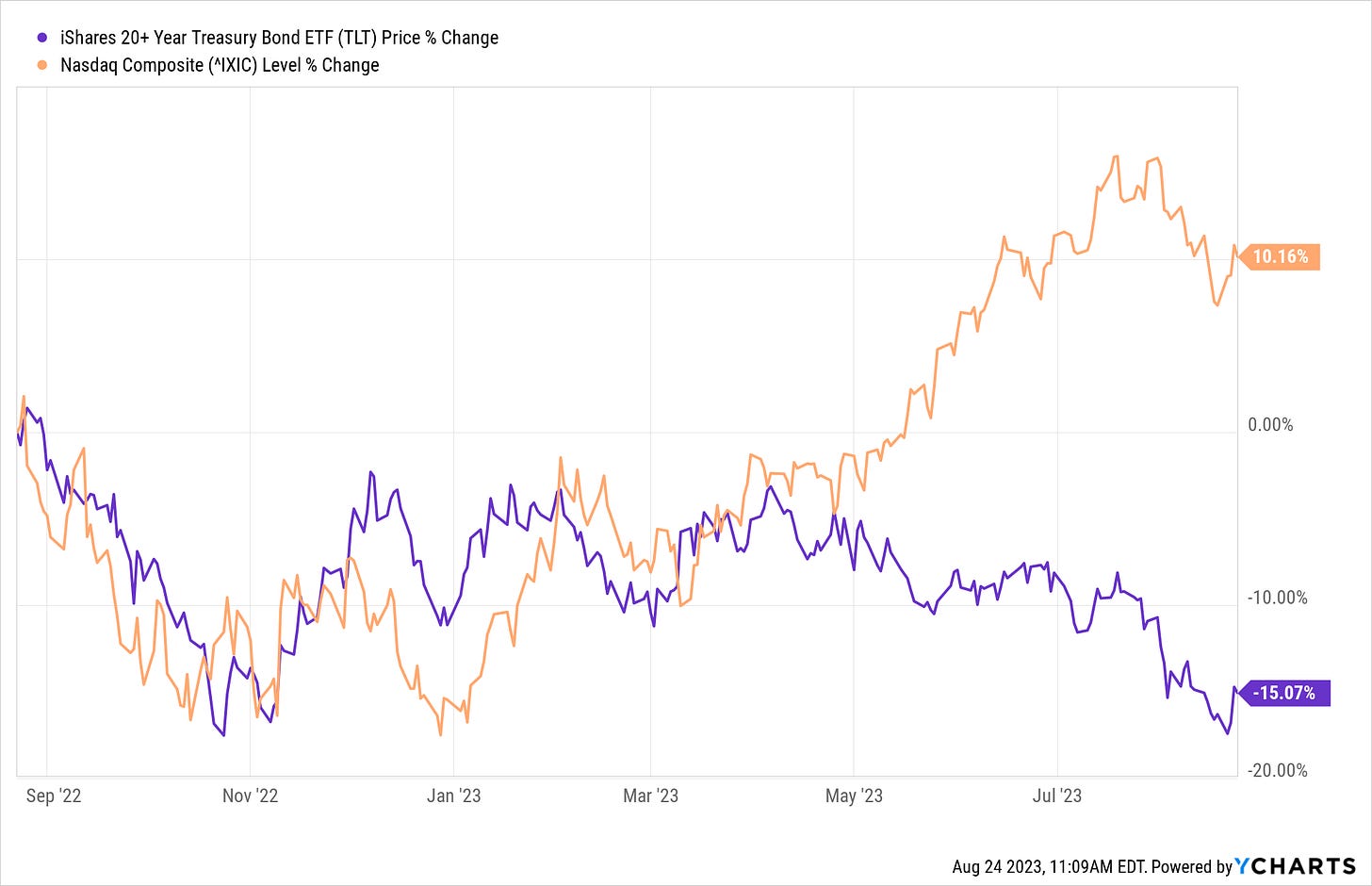

Various iterations of the chart above are becoming increasingly prominent. Given the typically long duration of Nasdaq stocks, the normal relationship is for Nasdaq to move in line with longer-term bonds (e.g., TLT). This was the case until about April of this year. Then Nasdaq began diverging from bond yields.

This can happen from time to time for various reasons, not least of which is the prior correlation was spurious to begin with. In this case, the breakout of Nasdaq corresponds pretty closely with the explosion of the artificial intelligence (AI) narrative. As such, this is one more piece of evidence suggesting Nasdaq has gotten ahead of itself.

On a different front, the US dollar continues its upward surge since mid-July. While some of this is simply recovery from a sharp selloff in early July, the move also coincides with a rise in 10-year Treasury yields. If the European Central Bank needs to halt rate increases, and higher yields keep attracting foreign capital, the dollar could keep going up.

Insofar as the dollar does keep rising, it spells even more trouble for China which is already struggling to revive a flagging economy and stave off deflation from a troubled real estate sector. A strong dollar makes commodities more expensive and dollar debts harder to pay off. It’s almost as if these effects were intentional.

Politics

Strolling Toward a Shutdown ($)

https://thedispatch.com/newsletter/morning/strolling-toward-a-shutdown/

When the House returns to Washington on September 5, members have a long few weeks ahead of them: Speaker Kevin McCarthy has vowed to pass all 12 individual spending bills through committee, a feat Congress hasn’t achieved on time since 1977. In the 45 years since, Congress has opted instead for omnibus spending packages, packaging together all the smaller bills for easier passage. To earn the support of some Republican holdouts earlier this year, however, McCarthy promised a return to regular order.

Passing individual spending bills on their own, as McCarthy has opted to do, empowers his hardline Freedom Caucus colleagues to demand vast spending cuts in committee markups, heightening the likelihood of a shutdown. Freedom Caucus members have also signaled that they have no intentions of going along with a CR, at least unless McCarthy offers concessions to the group.

After having a good run in the theaters this spring, the “Debt Ceiling” drama reached an anticlimactic end in June. For better and worse, the new “Government Shutdown” show will be playing this fall.

This show will have all the same contentiousness, all the same issues and all the same characters. Freedom Caucus Republicans are determined to make a stand against bloated government spending but any bill needs to be also be approved by the Senate.

At the end of the day, any decision to effect a government shutdown would be a political calculation. According to the Dispatch, “Some in the GOP are confident that a shutdown will put the spotlight on Democrats’ runaway spending, but history has not been kind to lawmakers who’ve staked their careers on the gambit.”

Regardless, the serenity of warm, late summer breezes belie the turmoil building up in the political and economic landscape. With politicians on both sides auditioning for the presidential election next year, this episode looks to have a lot more fireworks.

Monetary policy

The big news this week is Jerome Powell’s speech at Jackson Hole. While this event has always been a platform for communicating broad policy objectives, the challenge for the Fed chair has become much greater since the Fed’s focus on “communication strategy”. Now, everyone tries to guess the points the Fed is just trying to talk up (an avoid actually doing anything about) so they can selectively ignore them. The result is everyone now gets to have their own interpretation of what the Fed really meant.

While the particular contents of Powell’s speech will be unavailable before this letter goes out, there are some topics that can be expected to get some air time. For starters, a broad overview of the economy and employment conditions would provide insights into inflationary forces, or at least how the Fed sees them. As such, it is also likely to provide context for how long short-term rates might remain in their current neighborhood.

There is an argument to be made for Powell to also extend his comments beyond this familiar territory of monetary policy. Powell, like most Fed chairs, has been disinclined to say anything too threatening to markets - which have responded in kind by providing plenty of political cushion for raising short-term rates. At this point, however, unrestrained markets may be counterproductive and pose a greater threat to the inflation fight. As a result, there is an opportunity for Powell to talk down markets. This could be done by emphasizing the potential for long rates to increase, by increasing Quantitative Tightening (QT), or by outright selling mortgage backed securities (MBS), among others. Any effort to do impose some discipline on the market would be an important signpost.

In addition, since the title of the symposium is, “Structural Shifts in the Global Economy”, it wouldn’t be surprising to hear remarks about geopolitical risks, which have periodically entered the lexicon of monetary policy discussion. It will be very interesting to hear the extent to which “structural shifts” relate to debt, inflation, and/or geopolitical relationships. Regardless, “structural shifts” certainly implies a break from the past and that should be perceived as a threat from those betting on “more of the same”.

Fiscal Dominance and the Return of Zero-Interest Bank Reserve Requirements

(A podcast with Demetri Kofinas does a nice job explaining the issues. The first hour is free.)

This paper by Charles W. Calomiris discusses the concept of fiscal dominance, “which is the possibility that accumulating government debt and deficits can produce increases in inflation that ‘dominate’ central bank intentions to keep inflation low”. One point is we are approaching the threshold of fiscal dominance. Another point is once that happens, inflation becomes structurally higher.

This is part of the “endgame” of sorts. While it does not literally spell the end of the US dollar-based financial regime, it will end an era of being able to ignore the consequences of overindulging in debt. It will also end an era of being complacent about inflation.

When I talk about the likelihood of inflation as an investment risk, this is exactly what I am referring to. Analysts who insist on focusing on recent CPI readings or attributing inflation exclusively to Covid-era supply shocks are being too myopic. The big inflation threat is cued up and ready to shock those who aren’t prepared.

Public policy

Big ideas aren't enough

https://www.slowboring.com/p/big-ideas-arent-enough (h/t - @michaelxpettis)

This is an issue for all kinds of political entrepreneurs. You can’t just come up with a nice-sounding, high-level message. You need the capacity to design ideas that make sense and work in detail. I’ve fretted before that the policy analysis capacity on the left has withered somewhat, but it’s borderline non-existent on the right.

But is that something the government can pull off? Published 17 years ago, Katherine Boo’s New Yorker article “The Marriage Cure,” remains one of my favorite pieces of journalism, detailing the uselessness of these Bush-era programs in terms of actually helping poor women with anything. Not only did lecturing people about marriage fail to achieve anything, but her subjects also struggled with banal issues like unreliable bus service that made it hard to stay employed. Having reliable bus service is not as useful as having a reliable life partner. But “spend money to run the bus more frequently” is a tractable idea in a way that “get everyone to have a stable marriage” is perhaps not.

This article mainly picks on Republican policies, but the main point is broadly applicable: Big policy ideas do not translate into effective policy ideas without good implementation.

Matt Yglesias highlights a number of “big” Republican goals such as “a massive revival of religious life, a turnaround of fertility trends, [and] a revolution in gender relations”. The major problem with such high ambitions, however, is there are not policies scaled remotely large enough to achieve them. There is no plan.

Yglesias considers this something of a shame because in his opinion, “conservatives have lots of winning ideas”, albeit on a smaller scale. He goes on to list, “Democrats are too soft on crime, too lenient about violations of immigration rules, ask too many sacrifices in the name of preventing climate change, tax too much, spend too much, and are generally too indulgent of weirdos”.

One interesting point is the emphasis on effective policy relative to, what might be called, inspirational policy. To the extent voters react to what actually happens rather than just what is talked about, this is a fair point. Effectiveness almost certainly wins out over time. However, as we have seen, voters can remain enthralled by aspirational rhetoric for long periods of time, even despite any evidence of those aspirations actually being fulfilled.

Another point is the lesson is more broadly generalizable. Swap the context of politics for that of business, and the same principles apply. Leaders can talk about saving the world, eliminating fossil fuels, and using technology to solve every possible problem. Without a plan and without competent implementation, however, it’s all just guff. Eventually, clients and employees and shareholders realize this. When that happens, ambitious rhetoric sounds more like delusion and the lack of competent implementation looks more like weakness.

Business landscape

This chart from @SoberLook resonates for a couple of reasons. One is because it captures my own experience. A year ago, I used to get about one phishing attack a week. They were comprised of notices of incoming wire transfers, voice messages, bills that were due, etc. Most come with the logo of Microsoft or some other well-known vendor. Now I average more than one per day.

Another reason it resonates is because this is happening broadly across much of the business landscape. I don’t think this is a fluke. This is one manifestation of modern warfare - an attack on economic productivity with options to handicap critical infrastructure.

This affects the business landscape in a couple of ways. First, it is costly in terms of money and time and attention to deal with these regular threats. Second, there is an increasing probability that any given business suffers a catastrophic event. It could be a debilitating hack, the crippling of a major vendor, or any of a number of costly setbacks. While I don’t see this topping the chart of risk factors right now, I also think it is something that should not be ignored.

Investment landscape

Regardless of political affiliation, one thing people can normally agree upon is that government screws a lot of things up. Look at something like the ridiculously high amount of debt relative to economic production (amongst countless other serious problems) and you can’t help but to think no business would survive such ineffectual leadership.

I’ve had this thought many times myself, but my opinion is changing on the subject thanks to Neil Howe’s new book, The Fourth Turning is Here. His basic premise is that human history is cyclical, not linear, and the cycles last about the length of a lifetime. One consequence of this is the vast amounts of political capital that are required to solve big problems and to effect really meaningful change coalesce only about once every eighty to one hundred years! Think FDR’s New Deal.

Not only do big public policy transformations happen infrequently, they happen only in the most tumultuous and uncertain of times. Howe describes:

In fact, long-term solutions to big issues happen only when the nation reinvents itself. And that happens not on a sunny summer day—but on a dark winter day when citizens’ backs are against the wall and every available option points to sacrifice and danger. Paradoxically, the nation makes its most serious commitments to its long-term future precisely when its near-term existence seems most in doubt.

As a result, the decision-making environment in politics is extremely different than that for business. In business, decisions need to be made every day and therefore there is usually a clearly delineated decision hierarchy. Further, investments require money which is much more easily available in good times - when cash flow is healthy and/or the funding environment is amenable.

By contrast, government operates more on the basis of muddling along for decades addressing only relatively small issues on a regular basis. The biggest problems are repeatedly deferred until the rare moment, when in the heat of a crisis, it is finally possible to harness the political capital to resolve the biggest challenges.

In this light it becomes clear it is unfair to compare business decision-making with that in government. Managing political capital is a different effort than solving problems. This means it is at least somewhat unfair to be overly critical of the lowly merit of many public policy choices. Those choices are not so much reflections of hopelessly dysfunctional institutions (although there is some of that) as they are indications of normal (and long) social and political cycles.

The bad news is that can-kicking on big problems is the normal condition for democratic politics. The good news is those problems eventually do get addressed and solved, but only after a very long wait. During intervening periods, such as today, one of the greatest mistakes would be to read the environment as being hopeless.

Investment strategy

One observation from regularly monitoring advisory practices that always surprises me is the unusually strong adherence to the 60/40, stock/bond strategy. I get that stocks and bonds have been very, very good to investors for over forty years, but the evidence that era is over keeps mounting.

For starters, the biggest single driver of that forty year run was declining interest rates, and those rate declines were driven substantially by declining inflation. Performance was not driven by economic growth, which has actually been decelerating. At the same time, debt has been accelerating. Finally, the combination of Covid and the Russian invasion of Ukraine sparked public policy responses that uncorked the force of inflation. In short, things have changed.

In addition, financial history also makes a case against the 60/40 portfolio. While performance was strong over the last forty years, that performance stands out as being clearly anomalous over a longer history. An unusual confluence of beneficial factors in the past should not be the basis of high expectations for the future.

An important lesson to take from this changed environment is there really is no single strategy that can serve as a convenient anchor as 60/40 has done in the past. In fact, starting with a foundation of 60/40 is a handicap because the expected returns are so poor. As a result, starting with 60/40 and making modest tweaks is wholly insufficient. Finding other return streams, truly diversifying assets, and accepting higher than normal levels of cash are all efforts that can improve longer-term performance in current conditions.

One indicator of the strategic inertia of the investment advisory industry is the recent interest in Treasury bonds. Yes, stocks are expensive. Yes, inflation is trending down in the short-term. Yes, rates are significantly higher than they were. Yes, there is a good chance of a recession, or at least significant slowdown in the foreseeable future.

These arguments for bonds are still not very compelling for long-term investors, however. For one, the argument for bonds (over stocks) because stocks are wildly expensive is a false dichotomy. There are other investments too, not least of which is cash (which has an even higher yield than bonds right now). For another, the idea only has merit as a short-term, tactical trade idea. Finally, forces such as significantly increased Treasury bond issuance, rising Japanese bond yields, and the prospect of fiscal dominance (and therefore higher inflation) all pose serious threats to bond holdings.

Implications

One implication of stocks and bonds both being unattractive is it makes cash look relatively more attractive. Further, with interest rates pushing above five percent and inflation receding, cash looks pretty good on an absolute basis as well. As a result, this is one of those times when cash can play a really significant role in a portfolio.

That said, cash is highly unlikely to maintain its relative attractiveness indefinitely. At some point, stocks or bonds will get cheaper, inflation will threaten to rise again, or some combination of all of these.

As I have mentioned many times before, one of the areas I would like to deploy cash is to commodities, but they are very sensitive to timing. There is an ongoing tradeoff between long-term supply constraints and shorter-term demand and liquidity risks. Likewise, I continue to monitor the ongoing tradeoff between the inflationary force of rising labor costs and the deflationary force of falling real estate prices. In addition to these considerations, the fuse is lit on the debt bomb and it’s only a matter of time now before more aggressive (and inflationary) responses will be required to deal with it.

All of these will provide signals as to when and how to deploy cash. For now, it is fine to wait and watch, but that won’t be the case forever.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.