Observations by David Robertson, 8/9/24

Anyone who was hoping for a nice quiet few weeks in the markets to relax picked the wrong weeks. One momentous event keeps leading to another. Let’s take a look.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

Last week I said, “Stocks ended July looking pretty shaky”. Well, August has started off pretty shaky as well. The week started off with stocks in Japan falling 12% overnight on Sunday and that triggered a 3% selloff of the S&P 500 on Monday, the largest in almost two years. Tuesday proved its “turnaround” nature with stocks rebounding by a percent. Wednesday started strong and finished in the red. Thursday posted the largest gain in almost two years and finished within spitting distance of the close from the prior week.

One of the distinguishing features of the selloff was the prominent role of AI (artificial intelligence) stocks. As themarketear.com ($) illustrates, AI stocks led the way up all year and have led the way down over the last month. A classic case of “stairway up, elevator down”.

While the selloff has been notable, it certainly hasn’t been historic. Nonetheless, commentary has been especially shrill. As Jim Bianco suggests, “investment professionals who get paid to write newsletters freaked about the stock market over the last 14 days to a degree not seen in the last 37 years.”

Another important event was the 10-year Treasury auction - and it was weak. Treasuries rallied hard last week on weak economic news but just a few days later sold off hard. One point is Treasuries continue to bounce around more like penny stocks than the foundation of the global financial system. Another point is the selloff this week is NOT what happens right in front of a recession.

A really good thread by Tier1 Alpha lays out some of the implications of significant recent volatility. Many of the strategies that have ridden the coattails of low and declining volatility, got blown up by the whipsaw in volatility this week. As a result,

The loss of AUM in these strategies likely subtly changes market structure for the foreseeable future. Yes, we'll still see the $SPX rally as vol "normalizes," but the impossibly low realized volatility has likely retreated for good, just as we saw in 2018.

The question all this turmoil leaves is: Was this all a tempest in a teacup or does it forebode something more sinister? We might have gotten the answer from Warren Buffett, who had sold half his stake in Apple. Given Buffett’s inclination of extolling the virtues of American companies and given his favorite holding period is “forever”, the sale arguably signals something has changed. We can all take our guesses, but something, or some things, pushed Buffett to go against the grain and do something he almost never does. Consider ourselves warned.

Economy

The U.S. Job Market Is Better Than It Looks ($)

https://theovershoot.co/p/the-us-job-market-is-better-than

It is clear that the torrid pace of job churn, employment growth, and wage increases that characterized the post-pandemic recovery is over. But a closer reading of the latest indicators suggest that the underlying situation is far more stable, with less of a wage slowdown and a negligible increase in joblessness outside of the margins of the labor market. The question is whether these benign conditions will continue under the current policy setting.

I have seen quite a few analyses of the employment data from last week and most have passionately argued the labor market is falling apart - which just happens to conform with the narrative of weakening US growth. One of the more notable aspects of Klein’s report is the suggestion that maybe, just maybe, July’s unemployment rate was anomalously high due to people missing work due to bad weather (see graph).

Lee Adler also put out an edition of the Liquidity Trader ($) this week that featured the labor market. By his analysis of withholding taxes (which tallies real jobs, not imputed ones), employment numbers were down a bit, but nothing out of the ordinary in the context of very regular quarterly cycles. He described:

The economy seems to expand and contract every 3-4 months like clockwork. We can’t conclude from this data that there’s any reason to panic, yet. So far, this looks normal.

These two analyses both suggest the market’s reaction to weak data points last week was impulsive. Data bounces around, there is noise, and sometimes there are anomalies. My read is that a lot of people are seeing recession because that is what they want to see. I think the weak reports are mainly noise at this point.

Law

Big Business Take Note: Rule by Judiciary Isn’t the Boon You May Think It Is

In this new world of administrative law, it could take five years or longer for regulatory actions to wend their way through the overburdened court system before they become technically final and binding. If interested parties can find or create a new plaintiff in the years after that, the “final” rule can still be challenged under Corner Post on different grounds. It doesn’t matter what the subject matter is — environmental law, securities law, internet rules, labor law, consumer protection, banking law — it’s conceivable that some administrative rules will never have the force of settled law.

For reasons that are hard to fathom, lobbyists and others opposing the so-called “administrative state” and regulatory overreach don’t appear concerned about what the new rulemaking model will mean for them when the political worm turns and agencies start issuing regulations that businesses actually like. They seem to forget that competitors and public interest groups will have the same power to delay through litigation and to prevent any “good for me” regulation from becoming reliably final.

This is a really nice, high-level assessment of the implications of the Loper Bright and Corner Post decisions by the Supreme Court this summer. The decisions have the effect of making “federal judges rather than presidentially appointed financial regulators the deciders on technical issues of all sorts.”

While corporations have lauded the ruling to switch the “deciders on technical issues” to judges from appointed regulators, the switch comes with a lot of baggage. That baggage includes long delays for regulatory actions, the openness of rulings to attack from multiple directions, and ultimately, the lack of “finality” on rulings. The paper concludes, “There’s a serious practical problem with this. In many respects, knowing what the rules are is more important for successful business planning than the content of any particular rule.”

True enough. Much of the early celebrating seems to be related to winning a cultural battle rather than to truly improving business conditions. This has all kinds of potential for unintended, and mainly bad, consequences.

Technology

BOOM: Judge Rules Google Is a Monopolist

https://www.thebignewsletter.com/p/boom-judge-rules-google-is-a-monopolist

"After having carefully considered and weighed the witness testimony and evidence,” wrote Judge Amit Mehta in his decision of the case United States of America vs Google LLC, “the court reaches the following conclusion: Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly. It has violated Section 2 of the Sherman Act."

But this case is critical to freeing the web. As a colleague once told me, “Going after Google for anything but search is like trying to deal with Standard Oil without touching oil.” So there we go, Google’s control of the web is ending.

While we’re on the subject of legal decisions likely to have a significant impact on the investment community, this decision against Google also ranks right up there. It has been easy to dismiss these types of cases in the past partly because they have so rarely succeeded and partly because even when they do, remedies have rarely been intrusive enough to materially change business dynamics.

That historical pattern looks set to change with this decision. For one, there is likely to be a meaningful impact on Google because this addresses its core cash-producing business, search. For another, the implications are far-reaching as to what constitutes accepted practices across all businesses. Stoller writes,

Well, this decision means monopolization law is back. Exclusive contracts and arrangements are pervasive in American commerce, and until recently, executives could reliably exploit such deals

So, this decision looks likely to put a big chink in the armor of Big Tech, which also happens to have been a major driver of the market for years. It is also likely to reverberate across the entire business world. It won’t happen overnight, but things could start looking a lot different.

Investment landscape I

DEFLATION? REALLY? ($)

https://www.russell-clark.com/p/deflation-really

The problem with the deflation story is that it that bond yields have already proven themselves to be a policy story more than a macro story. Do you remember when every economist and hedge fund manager was telling you that the unwinding of the Chinese property bubble would be the GFC on steroids. Chinese property developers have gone bust in droves, and property starts in China has collapsed. And yet US bond yields have remained fairly high, and JGBs remain in bear market.

Looking at US policy going forwards, both Trump and Harris I think would like to restore US manufacturing to its former glory … Could policy restore this? I think they are going to try - and it will not be deflationary!

One of the key points here is one I have been making for some time: bond yields are “a policy story more than a macro story”. This has been hard for a lot of economists and fixed income people (including really good ones!) to accept because they are so deeply rooted in the belief that Treasury yields tell the “truth” about market conditions. Ever since the Fed embarked on Quantitative Easing (QE) almost fifteen years ago, however, with the express purpose of artificially lowering yields for policy purposes, that assumption has not been true. This means using Treasury yields as a read-through on the economy and inflation can be downright deceptive.

Instead, as Russell Clark highlights, it is more useful for investors to look at government policy than economics for clues about future inflation. On that front, neither major party appears as if it would be willing to sacrifice much higher unemployment in order to keep inflation down. As an example, “the number of US government employees has recently risen to new highs, after a long period of stagnation.” At least it appears the Biden administration is willing to pull whatever levers it needs to in order to keep employment up.

The key takeaway is that one’s view on future inflation depends on whether you believe government policy or economics is the more dominant cause. Clark argues for government policy (and therefore higher inflation) and I agree. The fact that a lot of smart people seem to be stuck in the economic weeds on this issue suggests the potential for a great deal of disappointment ahead.

Investment landscape II

Monday opened with a bang as the Japanese market was off 12% overnight and the S&P 500 lost 3%. The top two theories for the selloff were weakening growth in the US and the unwind of the Japanese yen carry trade.

While some commentators were inclined to focus on behavioral causes (i.e., panic), those explanations belie the structural forces at work. For example, because carry trades are leveraged, positions must be sold quickly in order to prevent existential losses. This is forced selling; no deliberation or emotion is required.

In addition, motivated trading increases volatility. Further, as Mike Green posts, volatility as measured by the VIX index has become much more sensitive as large volumes of volatility have been siphoned off to 0dte (zero day to expiry) options. As a result, when volatility does move up, VIX moves up a lot.

A rapidly increasing VIX then causes problems elsewhere. Virtually any risk-managed fund uses some form of value at risk (VAR) model and a good chunk of those use VIX as a key input. So when VIX goes up, VAR goes up, and if it breaches risk thresholds, securities must be sold. Again, forced selling.

One of the ways this gets manifested is in clearinghouses. Since these organizations tend to use similar backward-looking risk models, yesterday’s inflated volatility is used to set today’s margin requirements. Russell Clark ($) explains:

So why have markets moved so violently? Well I have to go back to the way clearinghouses price risk - which is backward looking. So even though the BOJ has been talking about raising rates, clearinghouses not have anticipated any volatility until it actually happens. Once volatility spikes, THEN they ask for more initial margin, which then causes more volatility and so on so forth. As I pointed out, clearinghouses create more financial volatility, and likely bankruptcy.

So, one takeaway is the selloff thus far is NOT mainly about some kind of investor panic. Rather, it is mainly the result of very mechanical processes that happen when something changes and volatility increases.

Another takeaway is that there is no single or simple explanation for the selloff. Concerns about weakening growth are part of it, and the carry trade unwind is part of it, but there are lots of moving parts. The ambiguous and multi-factor causes are especially problematic for mass media coverage which prefers very simple narratives.

Perhaps the best depiction of the selloff is that of a sandpile, an example often used in chaos theory. Once the pile gets big enough, it’s impossible to know which incremental grain of sand will cause the whole thing to fall down. In this sense, this little volatility episode is a healthy reminder of just how fragile the current market environment is.

To that point, the selling happened in the context of banks and other institutions still holding a lot of long-term Treasuries that are underwater and a lot of commercial real estate that won’t be able to get refinanced at economic rates. Some have been teetering on the brink for over a year. It won’t take much of a push to shove them over. Kinda feels like early 2008 with Bear Stearns.

Investment landscape III

With a lot of investors feeling rattled after a rough Monday, calls for Fed rate cuts started swirling around immediately. As Andy Constan points out, however, the heightened prospect of rate cuts may be a misread of the landscape. Instead, he claims, “STIR [short-term interest rate] market is broken and may not be predicting- ‘recession’” He suggests short rates are indicating a “panic to cash”.

This is interesting. While the phrase, “cash is king” hasn’t been heard much lately, that’s exactly what he is suggesting is going on.

Further, he suggests we are still in the early innings of this phenomenon. For starters, “over leveraged long risky assets … have yet to be even close to being fully unwound”. As he expounds in another post, the “Simple Yen Carry Trade (YCT)” is “just a version of a margin call”:

So 1. Risky asset selloffs cause a vicious cycle of deleveraging which 2. If leverage is denominated in Yen causes a yen squeeze which 3 may result in repatriation which further influences the cycle It ends when risky assets become attractive to leveraged investors. NOT to unlevered investors as the quantities are not equal. When that happens and the Yen becomes unattractive the cycle ends.

So, while asset prices are likely to bop around day-to-day, the trend will be down as this “vicious cycle of deleveraging” continues.

Implications I

Given the increasing prominence of government policy in determining inflation and the deleveraging of risk assets, it will be very important to monitor policy actions and communications for clues. At what threshold do stimulative efforts kick in? Are they fiscal, monetary, or both? How big are they? The answers to these questions will be very important in shaping the investment landscape for the remainder of the year.

To this point, the Deputy Governor of the Bank of Japan (BOJ) on Wednesday suggested suspending its rate hike due to market instability. Was this a useful early signal of policy direction?

If so, it represents a fairly rapid capitulation by central bankers. The same dynamic is also apparent in the States as recent market turbulence has fostered cries for two or even three rate cuts by September.

If central bankers actually do capitulate amidst relatively modest adversity, it will be virtually impossible for monetary policy to impose any kind of financial discipline - and that would have its own consequences. Paulo Macro makes it pretty clear that cutting short-term rates so much now would cause long-term rates to spike higher:

What is perverse in all this is the crying for Fed cuts. Do people not realize that Fed cuts would throw gas on the bonfire by narrowing rate differentials on overdrive and scream JPY higher and USD lower? The bond market would implode.

On the other hand, the BOJ may just be jawboning markets to temporarily placate them. This would indicate a much stronger commitment to the normalization of monetary policy. While it would signal a reasonably orderly unwinding of the carry trade, it would also indicate a more thorough unwinding to come. Given the many years the carry trade has been in effect, the unwinding is likely to take quite some time.

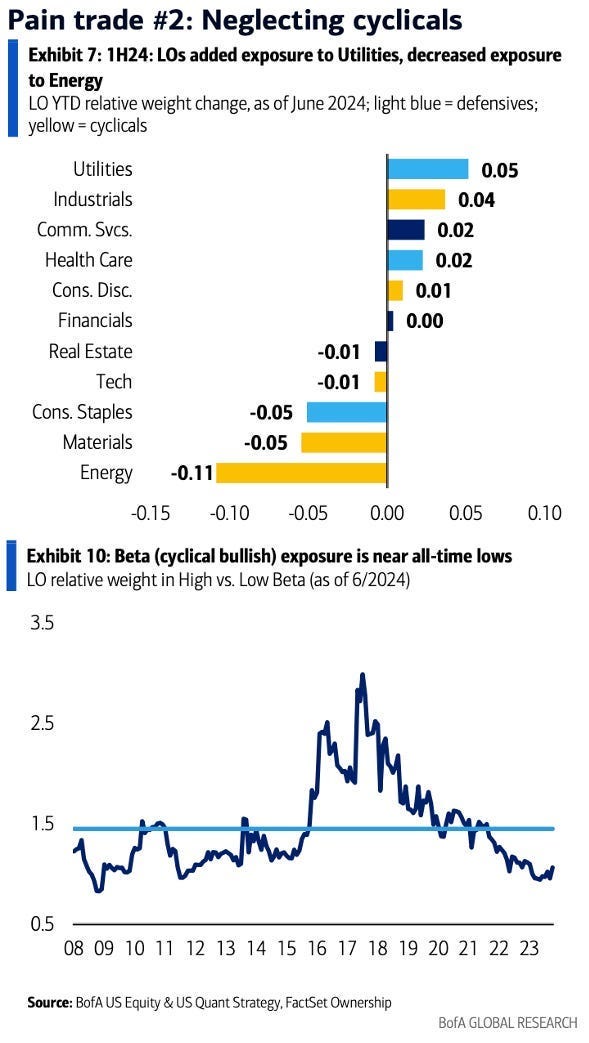

Another element of the current landscape is fairly extreme positioning for imminent recession, even though there are still plenty of signs of decent growth. Paulo Macro also illustrates the extreme under-exposure of investors to cyclicals right now.

If recent weak data points turn out to be noise/anomalies as both Matt Klein and Lee Adler suggest, investors could be surprised by the strength in cyclicals later this year if/when the data normalizes.

Implications II

While it looks like the market has recovered from jitters earlier this week, it still makes sense to consider the prospect of investor nervousness causing a self-fulfilling selling spree, i.e., a panic.

As Paulo Macro points out, an important risk of “piling on” comes from the corporate sector:

Critically though: since stocks=economy because of the financialization of everything (CEOs halt capex and do mass layoffs to preserve margins when they see their stock plunging), then ultimately a hard landing is purely a policy choice of whether or not and how much to goose the markets with monetary and fiscal.

In addition, there is also risk from individual investors. Due to the phenomenon of loss aversion, people tend to experience losses more intensely than gains. Also, long-term holders of stocks have enormous gains to enjoy. It wouldn’t take much loss for a great deal of pain to be felt.

The implication is there is potential for any selloff to spiral downward if investors flip out and exacerbate the situation with more selling. While the policy goal is always for orderly markets, sometimes that is tough to achieve. Personally, I don’t think a big, sharp, panic-induced selloff is very likely, but it has to be considered as a wildcard. That said, I think the more likely scenario is an extended, bumpy, downward trend in major stock indexes.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.