Observations by David Robertson, 9/23/22

There’s nothing that says “back to work from summer vacation” in the investment world like the first FOMC meeting since July. The expectation of an “interesting” fall still holds. As always, let me know if you have questions or comments at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

There are a number of stocks that reflect speculative interest because of leverage, alluring narratives, or charismatic leaders. Perhaps no other area captures speculative interest as well as options though.

Options are, by construction, leveraged bets and can easily go to zero. Further, the shorter the term of options, the greater the amount of luck involved and the less skill. By these metrics (as shown below from https://themarketear.com/premium ($)), speculative interest is as high as it has ever been.

As Binary As It Gets: Bulls, Bears and the Pivot ($)

Broadly, the bulls think that there will be a recession, but a shallow one that is already over by the end of 2023 thanks to the Fed. Bears think the Fed will still be tightening the screws a year from now and that the economy will be slow.

John Authers provides a pretty good assessment of market sentiment here by describing it as “binary”. While accurate, such sentiment also seems far too simplistic so I will take option c), “none of the above”.

If the Fed is unable to get what it wants, i.e., price stability and maximum employment, and I think this is quite likely to be the case, then the Fed will be stuck trying to make the best of a bad situation. Since either higher than desired inflation or lower than desired employment come with their own set of political perils, it looks to me like the Fed will be relegated to chasing after whichever mandate creates the most political pushback at the time.

This will cause the Fed to vacillate on its priorities which will undermine its effectiveness in pursuing either goal. Over time, this will also serve to further erode confidence in the Fed.

Back to the main point, however. In any but an incredibly fortuitous set of conditions for the Fed, the “binary” set of expectations miss any number of other possible outcomes. In short, the vast majority of mental models are set for well-traveled paths, not rocky roads.

Economy

One useful historical pattern is that oil does not normally affect economic growth in a material way until it breaches the threshold of about 7% of GDP. Mike Rothman explained this in a podcast ($) with Grant Williams earlier this year. He noted, “If you look at the world, when we get up to about 7% of GDP, which is income, if you think of 7% GDP being spent on oil, that’s kind of a real choke point, that’s a very problem point.”

The chart above from @Andreassteno highlights the challenge for European countries. While there may be some definitional issues since Rothman refers to “oil” and Steno Larsen refers to “energy”, there is still useful information content here.

After hovering right around the 7% threshold last year, every country is above that this year, and some are well above. This means high energy prices will act like a tax and will take away from other spending - which in turn will lower economic growth.

Eurozone

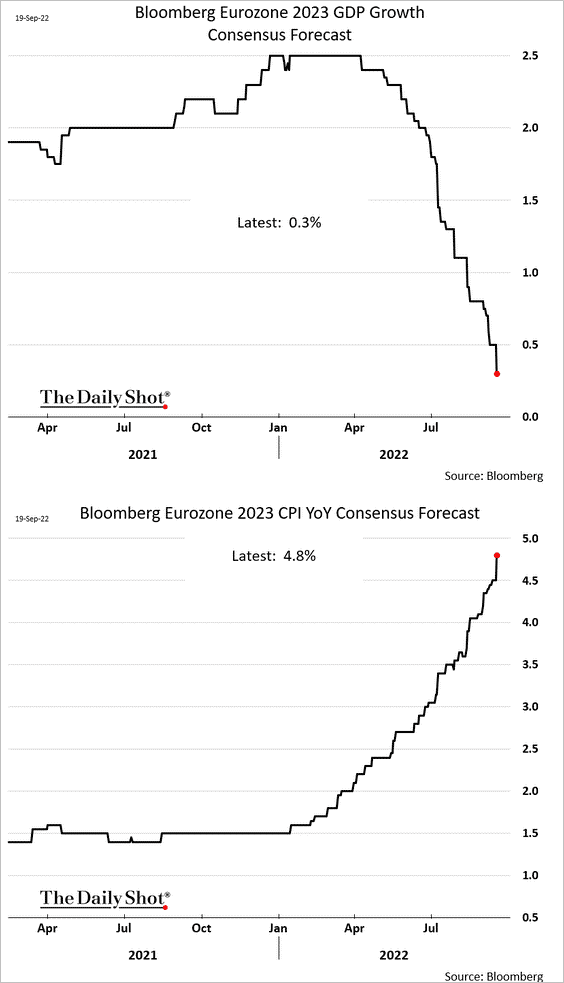

This graphic from @SoberLook shows how GDP forecasts for Europe have crashed during the year while inflation expectations have rocketed. What I find most interesting in these is the GDP forecast didn’t change at all until well after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In addition, while CPI forecasts did creep up initially, they didn’t reach levels that could be considered high until much later as well.

As a result, this contains some useful information. It reveals that market expectations did not change materially at all with the Russian invasion. Rather, expectations only changed slowly and only after being defeated harshly and repeatedly. While this says something of expectations for growth in Europe, it also seems to be a global phenomenon.

Commodities

Regular readers know I have been debating commodities for quite a while now and generally am skittish about the short-term but constructive on the long-term prospects. One idea that came to me was to perform this thought experiment: If you exclude a return to normal as a valid option, and can only choose between inflation and deflation for the next few years, which would you choose as more likely?

This pair-wise comparison helps to crystallize the tradeoff. What is more likely, a deflationary bust like the GFC or the continued monetarization of excess fiscal spending? For me, the tables definitely tilt toward the latter.

While the abyss of debt deflation was incredibly scary for those of us who were there, central banks and regulators have made substantial progress in mitigating that possibility. Further, while politicians feared excessive spending after the GFC, now they are sanctioned by their electorates to spend freely.

The biggest remaining question is when does it make sense to add to commodities? At what point will supply constraints overwhelm demand destruction? I will be monitoring this closely through the fall and I imagine many others will as well.

China

Anne Stevenson-Yang, author of China Primary Insight, recently presented her views on the country in a webcast ($). A number of comments stood out including, “The economy is down and it’s not coming back. Two percent growth is the best case scenario.” Indeed, she lists “commodity price decline” as one of her “high conviction views”.

Commodities has been a big focus of mine, so I asked how much flexibility she thought China had to reduce demand for oil in response to price. She responded the country had “quite a bit of flexibility” and the “[price] elasticity is pretty high”.

She also provided some nice perspective on what is happening in the business environment. Historically, she said, “foreign companies have relied on pro-business policies”. The problem, however, is “policy has become more unpredictable and volatile.” This is driving companies away.

Those bemoaning bad public policy in the West might be surprised to hear it is arguably even worse in China. She describes the spectrum of policies as “abject disaster”. As a result, she would need to see “political transition” in order to get more bullish, but admits that is “unlikely to happen”.

Inflation

This graph from @SoberLook illustrates nicely how unusual the current gap between short-term and long-term inflation expectations is. This either reflects a situation that is unprecedented in the 45 years of history presented, or it suggests an imminent closing of the gap.

To the extent the closing of that gap is expected to come from short-term inflation rapidly falling, the evidence from the GFC suggests otherwise. The only other time the gap between short- and long-term inflation expectations became so large, short-term expectations only came down slowly, over a period of years.

Currencies/Money

Bloomberg recently sponsored a podcast featuring a discussion between two pre-eminent currency experts, Perry Merhling and Zoltan Pozsar. While I buy into Pozsar’s notion that something is going on with commodities relative to fiat currencies, I found several of Mehrling’s comments to provide useful perspective.

For example, Mehrling claims analogies to the 1970s are misplaced. He says, “1971 was not the end of the US dollar system, but rather the beginning of an extension of that system to the eurodollar”. Mehrling was also reluctant to characterize recent geopolitical conflict as the beginning of a period of de-globalization.

To that point, in Mehrling’s mind, currencies are managed by central bank coordination. This is what holds the US dollar system together. Conversely, when asked what could undermine such a system, he answered, “a crisis with central bank coordination would do it,” and listed the case of Sterling in 1931 as an example.

After having listened to or read several such debates now, I can’t help but observe a common pattern: The tenured professor tends to be more conservative seeing trends in the context of modest changes from past patterns and the sell-side analyst relates narratives of dramatic change. While I tend to believe some pretty dramatic change is in store, such discussions also remind me that change could take a lot longer than I think.

Monetary policy

The much anticipated FOMC meeting ended on Wednesday and investors got an updated view on the Fed’s assessment of inflation and guidance on policy. In short, there is still plenty of work to be done on inflation so don’t expect the Fed to start easing any time soon. The Summary of Economic Projections revealed a generally more pessimistic outlook for the economy along with a higher level of rates needed to quell inflation.

Once again, the market’s reaction to the press release and conference afterward looks something more like a seismograph than a market efficiently pricing in new information. The fact stocks were up before the meeting even when a fairly harsh 75 bps rate increase was expected gives some indication of the still-prevalent sentiment of hope over good sense.

Indeed, this captures the Fed’s dilemma well. The beatings (tight monetary policy) will continue until morale (stocks go down and inflation improves) improves.

Chartbook #151: Zugzwang - are we on the brink of a central banking paradigm shift?

https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/chartbook-151-zugzwang-are-we-on

Under the financial capitalism supercycle of the past decades, inflation-targeting central banks have been outposts of (financial) capital in the state, guardians of a distributional status-quo that destroyed workers’ collective power while building safety nets for shadow banking. The limits of this institutional arrangement that concentrates (pricing) power and profit in (a few) corporate hands are now plain to see. …..

What if Zugzwang is that last stage of a central banking paradigm, when it implodes under the contradictions of its class politics?

But are we really facing the implosion of a paradigm? Is our reality not something less clear cut? Rather than a collapse or an implosion, is it not more likely that things will continue as they have done since 2008, in an on-going conservative rearguard action, based on a series of makeshifts and half measures?

In another nice piece by Adam Tooze, he highlights that challenges present themselves not just to the Fed, but also to other central banks like the ECB. In doing so, he also addresses a broader issue - which is the tendency to think of crisis as the impetus for fundamental change.

For example, in response to the proposition of an “impending paradigm shift in central banking”, Tooze suggests: “In the Eurozone too, though as Gabor has brilliantly shown the logic of the existing institutional set up is coming apart at the seams, does it follow that the resulting tension will resolve itself in any logical way?”

He offers a different way of thinking about the crisis of the current moment. Rather, it can be considered “as an interregnum, a hiatus before a new more coherent structure emerges, whether ‘at the hands’ of central bankers or not.”

This is a very fair point. I, like many others, suffer from the affliction of viewing crisis as an opportunity to figuratively hit the “reset” button and develop much more robust and resilient public policy to replace what has often been the result of colossally poor planning.

That tendency, however, overlooks the fact that there is often little reason to believe incoherent policy “will resolve itself in any logical way”. While fundamental policy improvement is a nice wish, and certainly not impossible, I suspect the better baseline expectation for this moment in history will be as an “interregnum”.

Inflation protection

One of the best forms of investment protection out there are i-bonds - and they can be bought directly from the US Treasury. The only problem is individuals are limited to $10,000 in purchases per calendar year.

In the video below, Adam Taggart highlights a feature of i-bonds of which I was previously unaware. Apparently, an additional $10,000 per year can be gifted/received by way of the “gift box” feature. This means an additional $10,000 per year can accrue interest at attractive rates and be “delivered” to the beneficiary at some later date. In short, it is a way to double your exposure to i-bonds if you so choose.

The video is at least a little “salesy” and focuses a lot on incremental interest that can be received, but also provides some useful information on a useful investment idea.

Investment landscape

One of the main themes I have highlighted over the last year is the importance of focusing on the big stuff when major change is happening and not getting caught up in unimportant details. Two of the really big changes I see happening now are the trend of public policy solutions migrating towards inflation (and not deflation) and China inflecting to a much lower steady-state rate of growth.

Regarding the first point, the big change happened during Covid. With the prospect of lockdowns squeezing off growth, governments were enabled to spend in order to keep the wheels moving. By contrast, politicians did not feel they had such a luxury during the GFC. The combination of loose fiscal and loose monetary policy is the new gig and will be inflationary.

China is important too because it had become the marginal consumer of so many commodities - and that impact was felt around the world. No more. The days of solving problems with ever-higher credit growth are gone - as are the days of almost boring 10% annual gains in GDP. The new paradigm is much lower growth and a much greater focus internally.

Implications for investment strategy

One of the big implications of this regime change is neither stocks nor bonds are likely to perform well, and certainly not nearly as well as over the last four decades. I have made this point several times and it is why I think the traditional 60/60 stock/bond mix is likely to prove extremely disappointing.

This hasn’t been lost on other investment firms, many of which are now aggressively peddling “alternatives” to investors in order to help them diversify. Of course, many of these “alternatives” such as private equity and real estate, among others, are also very highly correlated with stocks and therefore do not provide effective diversification. Cliff Asness rightly points out in the FT, “When investors are looking to alternatives, just make sure they are actually an alternative.” Just because they have a different name, doesn’t mean they do what you want.

Another big implication is the increasing involvement of government in all matters of affairs. This is something that happens periodically across history but can really blindside investors who are rooted ideologically in “free” markets and have no personal experience with such heavy-handed intervention. The antidote is simple, if hard to implement: Wake up!

The first step is to accept government intervention is a thing and many people actually want it. Another step is to accept this isn’t about right and wrong but about what “is”. Finally, the big implication is when governments are pushed to the wall, they often react by changing the rules.

This makes investing in financial assets especially challenging and is something that normally takes quite a while to become fully appreciated. Stocks are most at risk because their valuation depends on a long stream of cash flows - and a lot of things can change over that time. On this front, it helps to remember, when a government is desperate, there isn’t much it won’t do.

That’s it - thanks for reading Observations!

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.