News flow was slower this week which is probably just as well. It feels like the calm before the storm of earnings season.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

A couple of highly anticipated IPOs came out in the last week and a half and briefly sparked the market’s animal spirits. Instacart priced at $30 and quickly rose to nearly $43 and Arm holdings priced at $51 and quickly rose to $69. Alas, the excitement was short-lived as both stocks have been selling off ever since. Both stocks are now very close to their IPO prices.

On a different note, while rising yields on US 10-year Treasuries have gotten most the headlines recently, there has been a strong supporting cast of other sovereign bonds as well. As the chart from @SoberLook shows, yields in Canada jumped on Tuesday when CPI came in hotter than expected. The news packed a punch as its effects were clearly evident in US markets as well.

In addition, quietly, and in the background, the yield on the Japanese 10-year bond has kept inching up as well. While the BOJ has remained elusive in regard to future plans for yield curve control (YCC), the potential for something closer to market determined rates is slowly getting priced in. The graph (also from @SoberLook) reveals yet another influence on US rates.

Ostensibly, higher rates have a potent effect on private equity (PE). Not only do higher rates disproportionately hurt the smaller businesses that comprise PE portfolios, but higher financing costs diminish the returns of those highly levered portfolios. Oh, and failure rates shoot up too.

Perhaps we are getting an indication of things to come. As Steph Pomboy notes, “[CIO] Musicco to leave Calpers after less than 2 years after driving push into private markets. But I'm sure it's all about wanting to 'spend time with family'“. Of course, lesson #1 in engaging in incredibly risky behavior is get out before the consequences can come back to bite you.

Commercial real estate

‘Doom loop’ time line, Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, September 15, 2023 ($)

https://www.grantspub.com/index.cfm?#

The Aon Center, an 83-story office building east of Chicago’s downtown Loop, was purchased in 2018 for $780 million. According to a new report by credit-ratings agency Morningstar, Inc., the building, Chicago’s fourth tallest, is worth just $414 million today, which happens to be less than the $536 million of debt that financed the transaction five years ago.

At this formative point in the down cycle, neither the buyers nor the sellers know what the assets are worth. They’ll need, perhaps, 90 to 120 days to figure things out, says Ashner, after which the tempo of transactions is likely to accelerate. By the time it’s over, on form, motivated sellers will be “dumping things.” One potential accelerant: Through the end of 2024, $900 billion’s worth of bank CRE loans and securities need to be paid off or refinanced.

This piece is a friendly status update on the commercial real estate sector. The good news is net charge-offs are still well within reasonable historical norms, even if up substantially from post-GFC lows.

The bad news is there are very few data points from which to judge the extent of problems. Since there have been very few transactions there has been very little price discovery - although that is starting to change. Early indications are things could get pretty ugly.

As I’ve mentioned several times before, commercial real estate cycles take a long time to play out, and this one is no different. We are still in the early innings although we are moving to a critical inflection point, probably next year, when funding runs out and properties must get sold regardless of price. As a result, things are likely to get a lot worse for commercial real estate and are likely to do so fairly quickly. Be careful out there.

Oil

Oil is the biggest commodity in terms of total value and over the last three months it has bounded from the low 70s to the low 90s. A big part of the impetus was Saudi Arabia’s unilateral production cut. So, what does this mean for the market?

The graph below (from Zerohedge ($)) shows oil busting a move while oil stocks, which normally follow oil prices in step, are now doing so only marginally. It is certainly possible oil prices have moved too far too fast. Indeed, as Rory Johnston points out in his Commodity Context Substack ($), speculative positioning is playing a role: “the net speculative position now sits at 9.8% (as a share of total open interest), which is the highest level since November 2022”. He describes the positioning risk as “squarely to the downside”.

Or, the problem could be with the stocks. As Zerohedge observes, hedge funds are now shorting energy stocks outright as a means by which to hedge an imminent recession. Of course, if such recession fails to arrive, the shorts could get squeezed and stocks would jump higher.

The sustainability of higher prices is another issue. There is no doubt higher oil prices cause problems for China, the world’s top consumer of commodities by a long shot. They also cause major problems for central banks. Not only do higher oil prices reveal themselves quickly and visibly in gasoline prices, they also permeate deeply into the economy through petrochemical products. Further, in this case in particular (due to Saudi Arabia’s voluntary production cuts), it is incredibly hard to discern how sustainable the price increases might be. If any combination of Saudi Arabia turning the taps back on, demand falling due to recession, or China cutting back on purchases, oil prices would most likely fall quickly.

As a result, the recent move up in oil doesn’t yet appear to have the makings of a long, sustainable uptrend. That outcome will also be influenced by central banks, however, which must decide how much of an inflationary threat oil prices present. It will be very interesting to watch the interaction between oil prices and central bank decisions in coming months.

Politics

US autoworker strike could not be more critical ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/bda59c3b-3038-450d-a0e1-46cd2654a555

This change [the wording of the final Inflation Reduction Act to stipulating the use of “domestic” labor as opposed to “union” labor] was not only due to pushback from Joe Manchin, the Democratic senator from West Virginia who played a key role in ensuring that the IRA was passed. It was also the result of strong lobbying by foreign multinationals, many of which want to use the American South — where many new EV jobs are heading since labour and environmental standards tend to be lower in these states — as, in effect, their own personal China.

The fact that this race to the bottom is happening on America’s home turf is one reason behind the strike. The UAW wants to ensure that workers who make electric batteries and other components in the new EVs get union benefits.

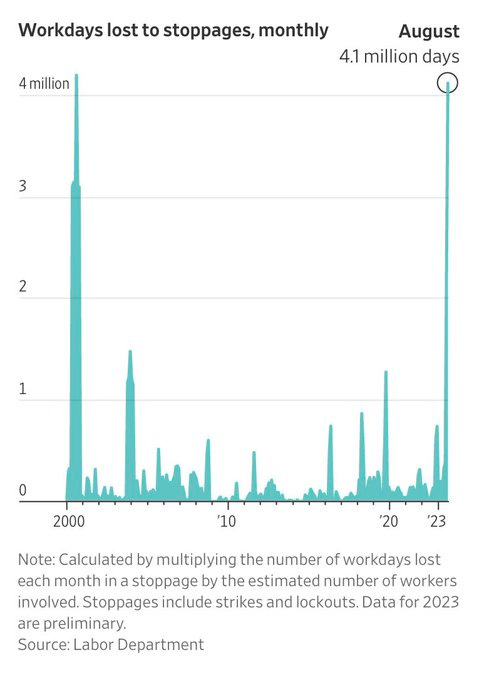

With more and more strikes in the news (see graph below from Lisa Abramowicz), it is an opportune time to review the underlying dynamics. For many years, the global economy took off due in part due to vastly increased global trade. While a lot of people benefited from this, it came largely at the cost of US workers whose real wages remained fairly flat despite regular improvements in productivity. In short, capital won at the expense of labor.

In one sense this makes many of the demands of workers today perfectly understandable. A big part of the effort is simply trying to regain ground lost over the years. As such, things are starting to swing back in favor of labor at the expense of capital.

What gets interesting is the problems it poses for Democrats. Historically the party with the most support for labor, Democrats had their fingerprints all over the neo-liberal era that saw workers lose jobs to China, lose pensions, and get divided and conquered such that many workers lost benefits and got stuck with lower pay scales. On top of those indignities, Democrats are now also pressing for more electric vehicles which threatens job demand for the entire auto industry.

Last year the Biden administration intervened to avert a strike by railroad employees. While there were extenuating circumstances, the action did nothing to confirm the administration’s endorsement of labor. As a result, the UAW situation poses a big risk. If the Biden administration does anything that might be construed as a hindrance to the UAW, it will come across as being pro-labor in name only and risk losing an important constituency. Of course, it is also possible the UAW wins big concessions and marks an important turning point for labor. Let’s see. I’m leaning toward the latter.

Monetary policy

The FOMC met this week and decided to keep rates unchanged. Commentary around the rate decision was unsurprising. The only items that were moderately interesting were the results of the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP). Back in June, projections for the fed funds rate in 2024 ranged widely from 3.5% to 6.0%. The new forecasts for 2024 ranged from 4.25% to 6.25% and were clustered between 4.75% and 5.5%; i.e., clearly higher.

As a result, the FOMC is looking more hawkish than it was three months ago. It seems economic growth has come in stronger than many of the FOMC members expected. The prospect of an imminent rate cut looks as distant as ever.

While perceptions of a quickly-caving central bank are fading stateside, policy divergence is emerging on the global stage. On one end, the Fed is remaining fairly tight and maintaining the option to become more so. In the middle is Europe which has been tightening, but has more inflation and weaker growth than the US. On the opposite end, China’s economy is weak and it is experimenting with ways, including monetary policy, to restart the economic engine.

Taken together, there are not only multiple cross currents, but there will be second- and third-order effects which will make the waters even choppier. This means it is getting a lot harder to use monetary policy as any kind of guide for market direction.

Investment landscape

One of the more prominent, recurring supports for the stock market has been share buybacks. The exceptionally low interest rate environment allowed companies to take out cheap debt to repurchase shares. Some companies just used internally generate cash flow. Either way, the amount of purchases has been big and has provided a near-constant bid for stock prices. I wrote a blog post back in 2018 on the subject highlighting how critical buybacks were to market pricing:

There is, however, a different and yet dominant influence on stock prices that rarely gets the attention it deserves. That proverbial "elephant in the room" is share repurchases.

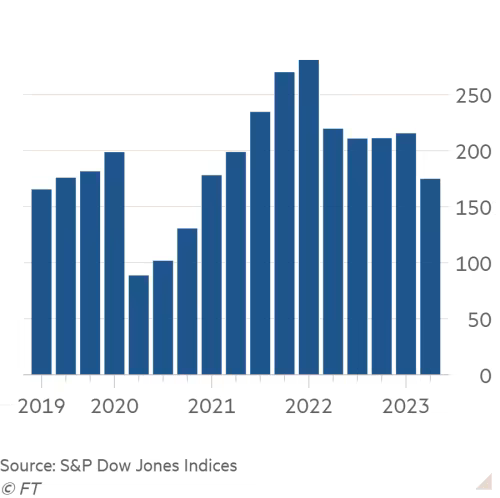

The chart below (from Deutsche Bank and referenced in the FT), though dated, still illustrates clearly where the demand for stocks has come from. It hasn’t been households or foreign buyers. The standout buyer of stocks has been companies themselves.

While the source of the buying has been pretty clear, the sustainability has been an open question. That question may be in the process of getting answered …

Buybacks’ moment of truth ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/56695b96-edde-4117-83fd-a441e7aa7ee1

“When rates were zero it made sense for companies to issue long-dated, low-rate debt and use it to buy back shares. Now not so much,” Carey Hall said. At the same time, businesses are facing increased pressure to invest in areas such as reshoring supply chains, automation and artificial intelligence and reaching net zero targets, she added.

In other words, the funding sources for all those share repurchases are starting to dry up. Long-term debt is no longer dirt cheap like it used to be so that doesn’t work.

Internal sources are also getting re-directed. Needs for capital expenditures and R&D are going up. At the same time, companies are starting to run out of room to raise prices even though costs are still going up. Margins are getting hit - which means cash flow is getting hit.

In sum, all the fundamental evidence points to lower free cash flow and lower incremental debt capacity - which means lower capacity to fund share repurchases. As it turns out, this is exactly what is happening.

What this means is there will no longer be a consistent bid for stocks - which means they will lose an important force to support prices. The only remaining question is when will this become apparent?

Chris Cole provided an outline several years ago on RealvisionTV ($) [here]: "I don't think it's any coincidence that the worst drawdowns in equity markets — we're talking about the period in 2015 or January 2016 or this recent February drawdown — I don't think it's a coincidence that they've occurred during the five week share buyback blackout."

So, we can probably look forward to at least a few turbulent earnings seasons.

Investment landscape II

Mitt Romney, Rory Stewart and the tragedy of politics ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/511ea709-a921-4ec2-9a36-34fa1b0216e9

Each man [Mitt Romney and Rory Stewart] took a stand against a blond-haired demagogue while other conservatives bent the knee. Each, in the end, failed. But in doing so, each illuminated an eternal fact about politics, one that people in business struggle to understand ... There are no prizes for being right.

Even the best-briefed people in the private sector get two things wrong about politics. First, they have no understanding of fanaticism. A life of negotiating deals — enforced by commercial courts — never acquaints them with people who have ruthless commitment to abstract doctrine. Perhaps some corporations, having let the cultural left in, are getting to know the type.

But the larger error is to believe that politics is as meritocratic as business: that one’s record of decisions must determine one’s career prospects. Why this is nonsense shouldn’t need spelling out. There is no quantitative value, no “price”, that can be put on most judgments in politics.

Now that government is becoming more involved in economic affairs, this note by Janan Ganesh in the FT serves as a timely reminder that the rules under which government operates are different than those under which business operates. Most shockingly for many, government is not a meritocracy; “There are no prizes for being right”.

In addition, the constituencies are different. Business can choose to deal with fanatics - or not. Government has no choice. It must deal with all-comers one way or another. Business would consider this a problem of adverse selection.

One takeaway is the disapproval ratings of politicians may be overstated. In an extremely partisan political environment, with a large proportion of fanatics on either side, disapproval is pretty much baked into the cake. No one could muster very high ratings in such an environment.

Another takeaway is politics is unpredictable. There are lots of reasons why and how political decisions get made. None of them need to conform to the standards and rulebooks of business. As such, politics can be largely indecipherable to businesspeople. At very least, it can seem, and actually be, incoherent and inconsistent. That being the case, it is useful to incorporate a higher level of uncertainty.

Implications

The last few weeks have felt like a waiting game. Economic data has been mixed but decent on average. We get a good report here, and a weak report there. Overall, the economy keeps plugging along while higher interest rates keep impinging on businesses that rely on cheap debt. Recessionistas keep waiting for the economy to blow up and inflationistas keep waiting for prices to spiral out of control. Yet neither has happened, at least not yet.

I do believe this earnings season could be an important inflection point - at least in perceptions. For starters, I do expect to hear of margin pressures as companies hit their limits on pricing power. In the environment of a share buyback blackout, however, share prices may be unusually vulnerable to bad news. To the extent any choppiness becomes more systemic and contributes to a broader sense of unease, investors’ perception of ongoing market strength is likely to be challenged.

In addition, there is a lot more to worry about than just corporate earnings. The UAW strike doesn’t appear close to being resolved and the prospects are quite good for a government shutdown. Outside the US, divergent monetary policy and pre-existing geopolitical tensions add to an already potent concoction of witches’ brew. This is a good time to hunker down.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.

Great coverage!! Thank you for sharing