Areté blog| Market review Q323: A change in the weather

The quarter started off strong enough in July but gave up ground in both August and September. The total return of the S&P 500 was down 3.27% for the quarter. Interestingly, the Vanguard balanced fund ETF, VBIAX (a good proxy for the 60/40 strategy), was down nearly the same amount, 3.24%, for the quarter. Clearly, the big increase in longer-term yields was a big factor for both.

But why did longer-term rates go up so much? Will they stay higher? How will it affect stocks and other assets? Digging into the details of what caused rates to go up provides some insights but falls short of providing the kind of understanding that can give investors direction. For that, a broader perspective is needed.

A list of explanations

A recent piece in the FT's Unhedged letter ($) did a nice job of chronicling possible explanations for higher rates. That list includes "Expected rate volatility is higher, perhaps because expected inflation volatility is higher", "Uncertainty around US solvency and/or political stability is higher", "Treasury supply has risen sharply, and will keep rising", "Foreign Treasury demand is not rising", "The marginal buyer may be growing more price-sensitive", "The balance of risks for bonds has shifted", and "The drumbeat of QT continues".

In addition, that list also "sanitizes" some of the more extreme views the commentariat has spewed out and to which investors must sort through. For example, several claims have been made that "Foreign Treasury demand is crashing". That's not true. As Brad Setser documents here, here, and here, various data problems make the determination of foreign Treasury demand a bit of a whodunnit. A lot of people don't do the work. The bottom line is it is more accurate to say, "Foreign demand is not rising".

This still leaves us some distance from any kind of satisfactory explanation for why longer-term rates went up so much, though. All of the factors listed have been around for some time. Why have they suddenly started to matter in the last few months? What changed?

One clue was provided by Jim Bianco in a post on X. He says the landscape changed with the pandemic in 2020 and neither investors nor policymakers have adapted to the different post-pandemic environment. Bianco defines the new environment by way of the following statements: "The answer may be that we are in a higher inflation world!!!", "The labor market has changed forever", "Deglobalization is a thing that is not going away", and "Energy output is now a political weapon".

As a result, Bianco argues, "a new understanding of how post-pandemic inflation works" is needed. Different environment, different rules.

Fair enough, but again, this post-pandemic environment has been around for a while. We still don’t have a good sense for why longer-term rates started poking higher again in July. What caused the bump higher?

Structural reasons

In order to make some progress on understanding the phenomenon, it helps to reframe the question. Rather than ask, “why did rates go up so much?”, we can ask, “Why didn’t longer-term yields go up before?”

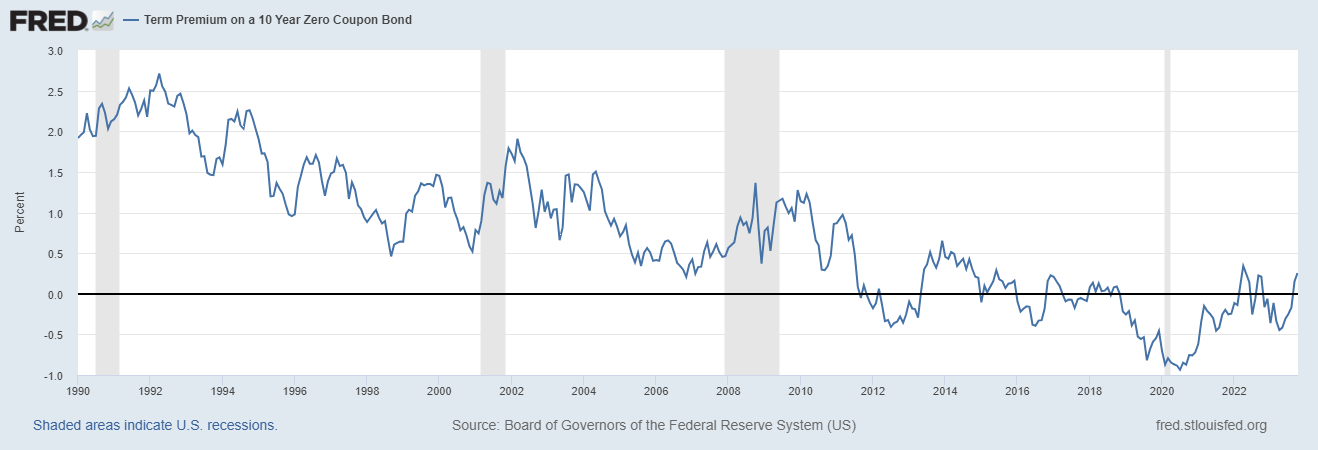

As the graph of the Federal Reserve’s measure of term premium (below) shows, the term premium steadily declined for years before hitting a low in the pandemic. Since then, it has risen, but remains in a historically low range. Since the term premium is an important component of long-term yields, along with inflation expectations, it provides some very useful context for understanding the movement in those yields.

Indeed, for those of us with a historical bent and an inclination to risk management, the negative, and historically very low, term premium earlier this year seemed out of place. At the time, I highlighted higher rates as "a possibility very few are discussing".

This assessment was based off insights from John Hussman and PauloMacro. In early March, Hussman posted, “if we restore a typical 1.0% premium to the average of core CPI, nominal GDP growth and T-bill yields, the 10-year Treasury yield might only reach 6.2%”. At about the same time, PauloMacro wrote, “And taking this a step further - my suspicion is the curve is deeply inverted because of a shortage of collateral. Once Yellen relieves this post debt ceiling, the term premium should explode and 10y goes >5%.”

In other words, the conditions for higher rates had already been set. Rates can be compared to balloons in this sense. You can keep a balloon aloft in the air for a long time by continuing to bat it up in the air every time it falls down close to the ground. You can also keep a balloon submerged under water by continuing to hold it there. But neither can be done indefinitely. Just as soon as the effort lapses, so too does the balloon gravitate (or float) to the surface.

Policy reasons

So, it is fair to say the term premium had been suppressed for some time. It is also fair to say that suppression served a policy purpose – to keep rates down in the post-GFC environment. It is also fair to say those policy inclinations are changing. As Sheila Bair describes in the FT:

The theory of Zirp (zero-interest rate policy) is that it boosts consumption and productive capital investments by making it cheaper for businesses and consumers to borrow. But the theory has not proved itself in practice. Economists have struggled to find a correlation between low interest rates and economic growth. Some studies suggest that higher rates are associated with higher economic growth. This is consistent with the US experience.

She goes on to document some of the negative side-effects of Zirp which read like the small print in a pharmaceutical commercial. They include undermining growth by making the economy less efficient, exacerbating wealth inequality, contributing to financial instability and disproportionately benefiting larger companies. In short, the medicine has become worse than the ailment.

It is also worth expanding Bair’s exercise by considering more theoretically what a higher term premium does in an economy. For one, it supports bank lending. When banks can lend long and borrow short, they make good money. When banks are healthy, there is ample capital available for lending into the economy. Positive term premia also discourage speculative finance by making it more expensive.

At the same time, positive term premia also encourage long-term investment in capital. When companies can be reasonably comfortable they can earn a good return from investing in manufacturing plant, they are far more inclined to increase supply. When term premia are negative, however, financial engineering is the easier and less risky alternative.

If these things sound vaguely familiar, it may be because they overlap the contours of industrial policy laid out by National Security Advisor, Jake Sullivan, at the Brookings Institute in April. In that speech, Sullivan laid out a blueprint for rebuilding productive capacity in the country. He also described how doing so would involve a reorientation of financial incentives.

This introduces another possible explanation for the increase in the term premium: It is part of a plan. It is part of a very deliberate (and ambitious) effort to shore up American industrial production and financial resilience, ultimately in service to national security.

Whether one agrees with the policy or not doesn’t really matter. It provides explanatory power. Rates are going up because that’s what the Biden administration wants, at least to a point. I even sketched out a playbook in last quarter’s market review to illustrate what the path might look like.

For those who may be inclined to nitpick, this theory does not account for every zig and zag of long-term rates. It is not a trading manual. There was a debt ceiling drama earlier in the year as well as a mini-crisis for banks. These things happen. The theory does, however, provide broad guidance for assessing bonds that can be useful for long-term investors.

Implications

One of the more important implications of this transition is it is unlikely to be smooth. As Bair describes, “Now that the Fed has shifted to a ‘higher for longer’ stance to combat inflation, our economy will have to make painful adjustments to the rising cost of money.”

In the US Treasury market, the absence of historically large buyers, combined with the prospect of much higher issuance for the foreseeable future, means the painful adjustment will involve the yield at which the marginal investor will be pulled in. While there is little danger of finding buyers for Treasuries, there is considerable uncertainty as to what rate will be required for demand to meet supply.

The process is likely to proceed something like a change over in industry. When an assembly line changes over from making one thing to making another thing, equipment needs to be changed out, tools need to be recalibrated, and it often takes a few starts and stops to get things running smoothly again.

Nor is the transition likely to be a quick, “pull off the band-aid” kind of adjustment. Bair describes, “The Fed is wise to pause to give our financial system time to adjust. Higher rates will help our economy, but a financial crisis could devastate it.” So, don’t read “pause” as a euphemism for the end of monetary tightness. Read “pause” as an “intervening break to facilitate a policy position of tighter for longer”.

While painful adjustments will be in store, they will not be uniformly distributed. Companies and consumers with too much debt will be hit the hardest. Inveterate gambling will become extremely difficult, if not impossible. Conversely, workers, savers, and well-run companies will all be in a position to do reasonably well.

Unfortunately, painful adjustments are also likely to be in store for the investment community. It will be hard to navigate mixed signals and periodic headwinds. Post-GFC signals and heuristics will not work well.

Because so many investors are so deeply indoctrinated in the post-GFC playbook, the transition is likely to be especially difficult for them. As Jim Bianco observed, “Bond traders have gone from bullish to dip buyers,” meaning there is no fear amongst bond buyers. He figures, “We are going to need a good old fashion capitulation to end this selloff (in bonds).”

In one sense this attachment to the low-rate playbook is understandable. It worked for about fifteen years which creates a lot of inertia in itself.

In another sense, however, it is much less easy to understand. Low rates were used as a policy measure in a low inflation environment. When inflation and geopolitical threats emerged, different policy was required. Conceptually the change is simple; it’s just a change in policy.

This ties into another implication. Because the risk of owning financial assets has been so low, the cost of risk management has been relatively high. As the risks associated with owning financial assets become increasingly evident, so too will the need for risk management.

Conclusion

Finally, the answer to why longer-term interest rates have gone up can most accurately, though somewhat obliquely, be attributed to a change in the investment weather. This change in weather was precipitated by a change in policy direction. While many investors remain stubbornly resistant to this explanation, they will start feeling the chill soon enough.