Observations by David Robertson, 10/15/21

Stocks have been bouncing around lately which is distinctly different than the upward trajectory they have enjoyed for the last year and a half. Earnings season is getting started so we should get some more clues as to what is going on.

Let me know if you have comments. You can reach me at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

The CPI data came out on Wednesday and inflation came in at an annualized rate of 5.4% which was above expectations. Even the core rate of 4.0% was high. Further, the owner’s equivalent rent (OER) jumped to 0.4% month over month indicating higher home prices are beginning to filter though into inflation. Notably, gold prices showed some life after the report.

The report stoked concerns about inflation, but also stoked concerns about policy responses. Long rates fell on Wednesday causing the yield curve to flatten, implying the Fed is going to inhibit growth by tightening. Another possible implication, however, is the Fed is mostly powerless to drive growth and fiscal spending will fail to take the lead when the time comes. Regardless, the Fed is painted in a corner that will be exceptionally difficult to escape with its reputation intact.

Energy

The age of fossil-fuel abundance is dead ($)

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/the-age-of-fossil-fuel-abundance-is-dead/21805253

“The industry would usually respond to robust demand and higher prices by investing to drill more oil. But that is harder in an era of decarbonisation. For a start, big private-sector oil companies, such as ExxonMobil and Royal Dutch Shell, are being pressed by investors to treat oil and gas investments like week-old fish. That is either because their shareholders reckon that demand for oil will eventually peak, making long-term projects uneconomic, or because they prefer to hold stakes in companies that support the transition to clean energy. Even though prices are rising, investment in oil shows no sign of picking up.”

“All this places fossil-fuel producers in something of a bind. A slump in investment could enable some oil, gas and coal investors to make out like bandits. But the longer prices stay high, the more likely it becomes that the transition to clean energy ultimately buries the fossil-fuel industry. Consumers, in the meantime, must brace for more shortages. The age of abundance is dead.”

With high energy prices comprising a significant proportion of the consumption bucket, recent precipitous rises are capturing attention. Attention is turning to concern when consideration is given to constraints on supply. In short, the world of ever-present, cheap fuel is over. Anyone who relies on cheap gas should be figuring out a plan B.

Expensive energy was the plan all along ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/20876c59-b438-43c0-8432-2b9f828f1b88

“The only thing that helps the climate is if demand falls with supply. Demand falls because of policy, and because technology drives the costs of the alternatives down, and capital goes into them. Some will say higher [fossil fuel] prices are what causes higher investment in alternatives. But they are going to cause a backlash against the climate policies that we really need.”

“What this [crisis] shows is how difficult, disruptive and messy this transition is going to be. Whoever thought we could replace the lifeblood of the world economy and that would be easy? It’s going to be super volatile.”

These comments from Jason Bordoff, the director of Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, highlight the link between high energy prices and public policy. Mark Latham from Commodity Intelligence corroborated this view in starker terms at the Global Independent Research Conference on Wednesday: He said, “this is a totally unnecessary energy crisis”, and also stated, “this is a political problem.”

Indeed, it is. An argument can be made that energy inflation is a feature of the political effort to reduce carbon emissions since high fossil fuel prices makes alternative energy sources relatively more attractive. However, consumers, especially in the US, want, and arguably need, cheap fuel to sustain their quality of life. Taking away cheap gas, even if only for a short period of time, is going to cause major political tremors.

That dissonance creates a major public policy conundrum. Which approach will win out? Should higher prices of fossil fuels be accepted as a cost of accelerating the transition to a more energy-efficient future? Or do historically cheap fuel prices need to be preserved to keep consumers happy (and solvent)? I think Bordoff is right, “It’s going to be super volatile.”

Logistics

The worst of the supply chain crisis is over ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/6478625f-1d62-4bd0-8a27-5ee3de6f36bc

“After most of the delayed deliveries are made, perhaps a bit after Chinese new year in February, then we can move on to the next political topic and meme: recession. After all, why will consumers order new stuff if it turns out they over-ordered in 2020 and 2021?”

“When all the goods are delivered by those truck drivers coming out of retirement, there will be a huge global pile of stuff that will not be reordered soon.”

The bullwhip effect is a common business phenomenon and one I reported on in Observations from 3/12/21. When vendors don’t get full allotments of their orders, they increase their order size to compensate. The actions and reactions cascade through the system until demand growth slows down and then everything reverses. Voila, an inventory recession!

Another interesting point was made by Manoj Pradhan, co-author of The Great Demographic Reversal, at the Global Independent Research Conference. Bottlenecks will clear over time since they are the result of idiosyncratic mismatches of supply and demand. As that happens, however, some areas will be exposed as having insufficient supply. As a result, there will be instances of inflation transitioning from idiosyncratic to cyclical. Once again, “super volatile” seems to be the best forecast.

Regulation

Rohit Chopra is going to rock the financial world ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/44043a25-16ea-48c0-862f-71de8472d0ff

“It’s about as big a change as you can imagine for an agency — it is in transition from an administration that essentially wanted to kill the agency and completely neuter its mission,” said Nowell Bamberger, a partner at the Cleary Gottlieb law firm. “Our expectation is that the CFPB is going to be incredibly aggressive in an enforcement context and incredibly ambitious in the context of rulemaking.”

Rohit Chopra, the new head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), went to Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton school of business and is described as “a fervent consumer advocate who favours stiff penalties for corporate bad actors”. This will be a big change and could present a big challenge for a finance industry that has adopted manageable fines as an acceptable cost of doing business.

Gensler To Wall Street: Prepare For The "Everything" Crackdown

https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/gensler-wall-street-prepare-everything-crackdown

“Gensler has already proposed 49 separate changes for his staff to consider implementing, the report says, calling it ‘one of the most ambitious agendas in the SEC’s 87-year history’. At the same time, he has kept an aggressive stance on ongoing enforcement actions.”

“Micah Green, a lobbyist at law firm Steptoe & Johnson, said: ‘If anyone underestimates his ability to get things done, they do so at their own peril’.”

Another new regulator (Gary Gensler) with a reputation for toughness is heading the SEC and sending a clear signal. While it is easy to shrug off the threat of heightened regulation given the light touch of the last several years, the new heads certainly have the bark; we’ll have to wait and see if they also have the bite. Thus far, we have seen body language pointing to tougher regulation but no material action. The market has been unimpressed.

I interpret this as fair warning: Financial firms should adapt to a cleaner way of doing business or face harsh consequences. Investors should beware of the potential for regulatory action to materially affect stock prices.

China

The picture that paints a thousand words for China’s markets is the graph of the Asia Pacific high yield bond ETF. This is not an illustration of “contained” or “just one bad apple” but rather a textbook example of the proverbial falling knife.

High yield is a good indicator here because it is the epicenter of real estate finance. Read between the lines a little bit and what you see is contagion spreading to other companies and related markets. Investigate the payments that have already been missed and all you get is crickets – there is no response at all.

This gives the distinct impression many real estate companies, banks, and the Chinese government itself are frozen like a deer in headlights rather than efficiently establishing restructuring plans. We will find out soon enough how bad things are, but thus far there are no signs there will be a quick turnaround in Chinese real estate.

Inflation

Does anyone actually understand inflation? ($)

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2021/10/09/does-anyone-actually-understand-inflation

“The idea of inflation expectations ‘rests on extremely shaky foundations’, he writes. First, he says, the theory is flawed. Models of inflation mostly include expectations as a short-term variable (that is, what prices will be in the next month or two). Insofar as expectations matter, though, central bankers and analysts think of them as a longer-term force, an underlying trend impervious to cyclical ups and downs.”

“But Mr Rudd’s contention is that the causality has been misdrawn. It is not that low expectations led to low inflation, but rather that low observed inflation led to low expectations.”

I first saw Rudd’s paper highlighted in Grant’s Interest Rate Observer and the Economist did a nice job summarizing it. The paper is provocative and irreverent – which makes for unusually entertaining material for economics – and it has gotten a lot of attention too.

More importantly, the paper challenges important economic orthodoxies. The main point, as I see it, is not so much that expectations for inflation don’t matter per se, but rather the subject of expectations has been treated far too dogmatically by the economics profession. A weak hypothesis gets traction, becomes embedded in models, and before you know it, drives economic policy.

Why Do We Think That Inflation Expectations Matter for Inflation? (And Should We?)

https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2021062pap.pdf

“What I believe such a response misses is that the presence of expected inflation in these models provides essentially the only justification for the widespread view that expectations actually do influence inflation. In other words, rather than simply serving as a plausible postulate that, once invoked, allows a theorist to analyze other interesting questions, the expected inflation terms in these models have been reified into a supposed feature of reality that ‘everyone knows’ is there. And this apotheosis has occurred with minimal direct evidence, next-to-no examination of alternatives that might do a similar job fitting the available facts, and zero introspection as to whether it makes sense to use the particular assumptions or derived implications of a theoretical model to inform our priors (particularly when the ancillary assumptions of the model are so incredible and when the few clear predictions it makes are so wildly at odds with the available empirical evidence).”

“In particular, a policy of engineering a rate of price inflation that is high relative to recent experience in order to effect an increase in trend inflation would seem to run the risk of being both dangerous and counterproductive inasmuch as it might increase the probability that people would start to pay more attention to inflation and—if successful—would lead to a period where trend inflation once again began to respond to changes in economic conditions.”

These quotes from the paper itself reveal that rare economist – the one who can think for him/herself. Rather than assuming only one possibility, he considers counterfactuals. Rather than assuming success, he considers the consequences of acting on theories that are wrong.

By asking good, common-sense questions, he seems to be partly shaming the profession for not being more introspective. Indeed, one can envision the author figuratively shaking the shoulders of fellow economists and imploring of them, “Wake up and think for yourself!” If Rudd can cause a little more curiosity and humility to swirl through the economics profession, he will have made an enormously valuable contribution. In the meantime, we can all take a hint and make sure we are not relying too heavily on specific inflation forecasts.

Investment landscape

Read the Runes. Inflation Is Showing Some Staying Power ($)

“Over the long term, ‘venture capital investing’ has been a disappointment. Returns have been significantly less than the equity market. The risk has been greater, and basically it has not been a good idea.”

“Venture capital is not about the money; it’s about the people… As we all know, life itself is unfair, and it turns out that only 10 or a dozen organizations are really successful at venture investing, and that means everybody wants to be investing with them or have them invest in their companies.”

If you scroll down to the bottom of John Authers’ Bloomberg article, you can find these insightful quotes by Charley Ellis, author of Winning the Loser’s Game. Venture capital, which is often considered an asset class (usually in combination with private equity) and referred to as alternatives, isn’t really an asset class at all. Rather, it is the good track record of a tiny subset of venture capital investors that is conferred upon a much broader (and less successful) universe.

This has enormous implications for investors. First and foremost, this completely disrupts the foundation of most allocation efforts. Assets are allocated based on risk and reward tradeoffs and on risk preferences. On this basis, many longer-term funds such as pensions and endowments, allocate relatively large portions of their funds to riskier investments such as venture capital and private equity.

Often, oversized allocations to riskier assets are made on the basis of “going out on the risk curve” and trying to increase overall returns. This where the fallacy gets exposed. Since the excess returns are a function of few good managers, and not the method of investing itself, the motivation is misplaced.

Further, there is adverse selection. The very best venture capital and private equity funds want clients who truly understand how they operate and who truly have long-term investment horizons. Funds and organizations that don’t have patience and don’t appreciate the investment proposition don’t make good clients and won’t be able to get into the best funds. This leads to a Zen-like paradox: The harder you strive for higher returns, the less likely you are to achieve them.

Another point is management quality is also relevant for other investment types although usually to a lesser extent. In other words, the construction of portfolios according to broad asset class returns misses a huge opportunity to both improve returns through good management, and to avoid bad returns through poor management.

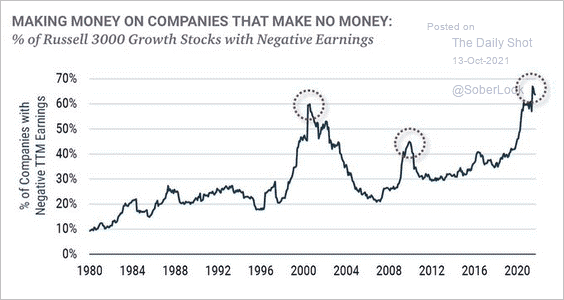

Another part of the investment landscape that is important to consider is the dangerously high percentage of public companies that make no money depicted below. When stocks stop being treated as partial interests in economic enterprises and rather as tokens that are traded in hope of selling for a higher price, the thesis of fundamental value evaporates and the proposition of owning stocks looks a lot more like gambling. Which saver for retirement really wants to own an index of which two-thirds is comprised of companies that don’t earn any money? This isn’t investing.

Implications for investment strategy

Inflation or deflation? That is the question investors are trying to figure out and was the subject of a discussion at the Global Independent Research Conference this week. The panel was loaded with heavyweights on the subject: Grant Williams, Russell Napier, Jim Grant, and Dylan Grice.

Grant issued a general warning with the suggestion, “the muscle memory of the last four decades has caused investors to expect anything but inflation.” He went on to describe the consequence: “It has conditioned people to disregard the usefulness of margin of safety.” I think this is right and suspect the lessons will be learned only slowly and painfully.

Grice delivered the most relevant investment insights. He explained, “all roads lead to duration.” In other words, the phenomenon of declining interest rates has been an enormous tailwind for a vast array of investment strategies. In addition, noting the many miscues on inflation the last several years, he suggested “we should have learned some humility.”

Given the broad exposure to duration and how little any of us truly understands about inflation, he prefers to “sit on the fence” and avoid taking big bets inherent to the ownership of stocks and bonds. His point is, “it is easier to find duration-free investments than picking the direction of rates.”

These are two incredibly important messages for investors. First, a lot of portfolios are inadvertently making big bets. If you have a balanced portfolio of passive funds, you are making a big bet against inflation. If you are trying to juice returns with private equity or venture capital, you are making a big bet against inflation.

Second, the best response to the inflation puzzle is probably humility. None of us know the answer so it is best to not invest as if we do. This will be especially important if “super volatile” price swings come to pass.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.