Observations by David Robertson, 12/20/24

Market news has slowed down in front of the holidays but plenty of other things are simmering just below the surface.

I will be off next week and return on January 3rd with a new Outlook piece. In the meantime, I hope you have a very Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays!

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

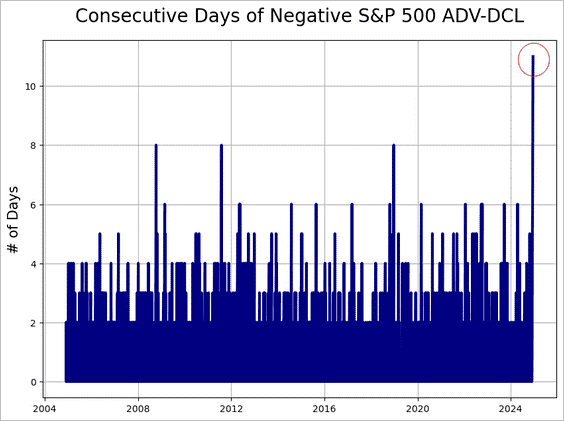

As of Wednesday morning, stocks had been on cruise control for the past two weeks. That flat performance belied a number of very interesting anomalies under the surface, however. One, for example, is breadth has been terrible. As The Daily Shot highlights in the graph below, “The number of declining stocks in the S&P 500 has outpaced advancers for 11 consecutive days, marking the first such streak in recent decades.”

As Jim Bianco points out, the Mag 7 stocks have carried most of the weight, accounting for over half of the gains in the S&P 500 for the year.

Another indication of disparity among S&P 500 constituents is the massive performance differential between growth and value styles. The Daily Shot graph below shows value has underperformed by over 30% this year, with the differential the last few weeks especially striking.

The calm outward demeanor finally cracked on Wednesday as the market reacted violently to the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting press conference. The S&P 500 was down nearly 3% for the day. The 10-year Treasury yield shot up almost 11 bps and the VIX volatility index, which had been skirting its natural floor of about 13, jumped to over 28 before receding.

Interestingly, the rate cut was widely expected but markets were jarred by a modest increase in inflation expectations and a modest decrease in rate cut expectations. The huge reaction probably had many contributors among which I would note increasing concerns about the omnipotence of monetary policy, a simple correction of overly enthusiastic trading since the election, and increasing twitchiness about prospects for next year.

Finally, Ben Hunt keeps all the recent market chicanery in perspective: “I think it’s important to document the MSTR madness for posterity. At this point, 5% interest on cash and cash-equivalents is now ‘earnings’ and gets a 50x multiple.”

Politics

It is unfortunate that our society has become so inured to violence, but it is also a reality that is hard to escape. Sure, the wide availability of guns don’t help. Lax enforcement in many areas is also a problem. Inadequate care for people with mental health issues is also a problem.

What is also a problem, however, is that a lot of people are getting pissed off at having been treated like crap for so long. The Occupy Wall Street movement emerged a decade and a half ago in response to massive malfeasance in the financial sector that was devastating for a lot of people but went almost completely unpunished.

Nor did the bad behavior stopped there. Companies make business models out of privatizing gains and socializing losses and of continuously pushing responsibilities down onto customers while simultaneously erecting barriers to smooth and equitable conflict resolution. As Rana Foroohar ($) puts it in the FT, “ At a very high level, I think there’s also a great sense of fury and apathy about corporate power and inequality, which seem huge, omnipresent and intractable.”

Eight years ago already Ed Luce ($) highlighted this phenomenon and labeled it “The American consumer’s impotent rage”:

Ask any American if they have lost their temper recently and there is a good chance it was on the phone to one of their service providers. Whether they were venting their spleen at a cable service company, a cell-phone operator, an airline or a health insurer hardly matters. What unites them is the impotent rage that comes from knowing how little you can do to punish the company in question.

As it turns out, I am especially sensitive to these things partly because I have a very low tolerance for being jerked around and partly because as a business and investment analyst I can see very clearly that in many cases I am being jerked around. The fact that I cannot get problems resolved quickly, that doing so requires an inordinate effort on my part, and that alternatives are often not any better are all the result of decisions — decisions made by executives to leverage corporate power at the expense of customers and decisions made (and not made) by politicians and regulators to allow these transgressions to thrive.

In an important sense, this is simply what it looks like when “capital” wins out over “labor”. Businesses get to keep on increasing profits by squeezing customers for both money and time and a frustrated and fragmented customer base has little recourse.

What I find especially interesting is there seems to be little political pressure on either major political party to address and correct this “impotent rage”. There are performative elements like President Biden walking the picket line with the UAW and Donald Trump stoking outrage in his campaign. There are also some small concessions like FTC chair Lina Khan trying to eliminate junk fees and the Republican pledge to eliminate taxes on tips.

Importantly, however, neither party has addressed the core problem head-on. This is why a lot of people do not feel well represented by their government — because they aren’t. So, does capital keep winning out over labor making life even more insufferable for consumers (and causing more discontent) or do the political winds start turning towards labor?

Public policy

As many of us have become overwhelmed by the myriad details of dealing with various retirement savings programs, it is easy to forget there are high level policy reasons for these programs. Toby Nangle outlines the UK pension scheme in the FT ($), but the ideas are broadly applicable:

Financial incentives to boost retirement savings exist to serve two principal policy goals. First, they reduce savers’ reliance on social welfare programmes in old age, easing the demographic burden on future taxpayers and enhancing fiscal sustainability. Second, they support investment, boosting economic growth and living standards.

In terms of supporting domestic investment, however, Nangle reports these plans “are proving increasingly dud”:

Despite derisking, a stable 70 per cent share of old defined benefit schemes are invested in UK assets such as bonds, equities and property. Newer defined contribution schemes that are set to replace them have no such home bias. According to the Department for Work and Pensions, just over half of DC assets were invested domestically in 2012. But by 2023 this share had shrunk to slightly more than a fifth.

This explains a lot. As UK (and many other) retirement plans shifted from defined benefit to defined contribution, those plans relied increasingly on global market indexes for allocations. As that happened, more and more money flowed into US markets, which boosted performance, which caused even more money to flood in from outside the US. As Nangle describes, “[the UK] government increasingly finds itself providing tax relief to higher-income households sending their savings overseas. This was not the plan.”

As a result, the policy is getting reconsidered. To the extent financial incentives are provided to retirement savers, those savings should do a better job of boosting domestic investment. While that tradeoff can be made in a lot of different ways, and probably will in different countries, the result is likely to be very similar: Large flows of money that used to come into US capital markets could slow or even reverse. That will likely create a mighty headwind for US financial assets.

Geopolitics

The government of Germany lost a vote of no confidence this week so another major Eurozone state will need to form a new government. Also this week, Canada’s Minister of Finance resigned which makes that government vulnerable to dissolution.

While news bits like these can appear as just miscellaneous pieces of background noise, they also comprise a widespread pattern of incumbent governments getting the boot, something I referenced last month in Observations from the FT ($):

the economic and geopolitical conditions of the past year or two have created arguably the most hostile environment in history for incumbent parties and politicians across the developed world.

That hostile economic and geopolitical environment is not just constrained to the developed world. As Michael Pettis reminds us, things are not getting better in China yet either:

In the pre-COVID years it generally required 3-4 units of debt to generate each unit of GDP growth. This year (and last year) it is taking more than six units of debt, which suggests that growth in China's economy is more reliant than ever on debt

The plummeting yield on 10-year bonds is a good indication of continued pressure in China’s economy.

So, at a very high level, the geopolitical landscape is fraught with excessive debt and slowing growth. Those problems are intertwined with national industrial and trade policies and the global financial system — and those problems are manifesting in political frustrations at the national level and in geopolitical frictions at the global level.

In a grander sense, this eruption of political and geopolitical tensions indicates both that major changes need to happen to the global financial system and that the path to get there is likely to be bumpy. Expect a lot more geopolitical “events” in the next year.

Investment landscape I

Pretty much since the beginning of the debate between active and passive management, passive has been extolled for the virtue of (generally) having lower fees. In more recent years, passive has also mainly outperformed active management. As funds have flowed from active to passive managers, large caps have gotten larger and actively owned stocks have been forcibly sold, regardless of fundamentals.

While this has all been well and good for passive investors, it is useful to be aware that other things have been going on in the background — things that could start to create real problems for passive investing. As Dave Nadig hints in a recent Substack, “But while passive investing works, it also perturbs the markets being invested in, and that’s worth exploring.”

More specifically, he describes passive investing as involving a paradox. On one hand, “The very best individual strategy to increase portfolio value is, on average, to buy the entire market at the lowest possible cost.” On the other, “The more investors take that advice, the more they ‘bid up’ the value of the market *as a whole* just through flow.” In other words, “something that is good for the individual can be bad for the whole. That’s the literal definition of the ‘tragedy of the commons’.”

While the “good for the individual” part has mainly been experienced to date, as passive continues to take share of the market, “bad for the whole” becomes a progressively greater risk.

The risk that is most salient for Nadig is that of market fragility. As he puts it, “What keeps me up is that all of this is going on in a market that, since Reg NMS and Citizens United, has largely been driven by speed and regulatory capture. Both of those have led to hyper-efficient systems governing everything from your Robinhood account to how non-traded bonds settle.” And, in short, “Hyper-efficient, mis-regulated, under-invested systems break.”

Investment landscape II

Mike Green has been a frequent commentator on the active vs. passive debate and he also introduces a fresh perspective ($). In his mind, the issue is not so much whether active or passive is better, but under which conditions they should co-exist. What he is really opposed to is “special treatment for systematic market-cap-weighted index investing that powers its growth far beyond what would otherwise occur.”

He goes on to list some of the special treatments:

1. Designation of QDIA (qualified default investment alternative) and liability protection

2. The ability to publish “backtests” of index performance

3. Failure to enforce diversification and leverage requirements from the ‘40 Act

4. Failure to designate the largest asset managers as Systemically Important Financial Institutions (SIFI) despite their obvious status as such

5. Failure to enforce ownership limits, and even more egregiously, not aggressively pushing back against attempts to use derivatives to gain exposure beyond legal limits.

In other words, Green’s beef is not with the passive approach itself but rather all the competitive benefits it receives in implementation. It’s just not a level playing field. In order to level the playing field, he proposes:

1. Tort reform to end the ridiculous practice of suing 401K sponsors. This has morphed from lawsuits on “excessive” fees to lawsuits on product selection.

2. Enforce antitrust to preserve investor access to listed products. There is no reason that employees (or brokerage clients) should be gated from accessing any product approved by regulators … there are real costs to brokerage platforms “pay to play” that extend far beyond the neatly observable hit to small fund company profitability.

3. Large investors should be penalized for choosing passive investing. This can take any number of forms, but the “simplest” approach is simply to penalize large investors generating returns without actively investing … Efficient markets are a public good; as a public good, there is a disproportionate responsibility that falls on the largest investors to NOT “free-ride.”

4. Large fund complexes should be penalized for size — the larger you are, the more you rely on (and consume) market liquidity in risk-off events, and the more cash you should be required to hold endogenously. It is insane that Vanguard is “allowed” to run a $1.6T fund with effectively zero cash; it is much more “insane” that we tell people this is the “safe” investment.

This discussion is helpful for at least two reasons. For one, it rightly acknowledges that efficient markets are a public good. Further, efficient markets don’t just happen; they are the result of competitive bidding from active firms to ensure good price discovery. It’s not fair or sustainable to steal those goods and not compensate for them.

Another reason the discussion is helpful is because it highlights many of the less well-known elements of the investing landscape that tilt the scales in favor of passive over active. While passive does have its benefits, it also benefits from an awful lot of unfair advantages.

At the end of the day, both active and passive approaches have their pros and cons; neither is inherently better or worse than the other. Green makes a very fair point they should at least be able to compete on equal ground.

Investment landscape III

A very simple post by Charles McGarraugh speaks volumes:

YOUR top risks of 2025:

* Deflation, inflation, Fed

* China macro

* Tariffs & immigration

* Geopolitics

MY top 2025 risks:

* Crowdstrike 2.0 but worse

* Grid resilience: solar flares/EMPs/etc

* UFO disclosure

* Hurricanes/cyclones

* Institutional instability

One point is that most investment strategy reports focus on the same issues which mostly tend to be widely known and well-discounted. This does not lead to significant insight that can be turned into materially better performance, however. His advice is to “Think different”.

This also harkens back to Nassim Taleb’s concept of “black swan” risk. It’s not the regular day-to-day risk that can wipe you out; it’s the things you can barely, if even, imagine. As pressure continues to build in the geopolitical landscape, it’s worth keeping an eye on the kinds of things that can metastasize quickly.

All that said, at a time of much higher than usual geopolitical pressure, I think McGarraugh understates the more conventional risks like monetary policy, China macro, and geopolitics. All of these are interconnected and can leak out into other risk areas or suffer big dislocations from rather small disruptions. In addition to thinking different about risk, I would add, “think a lot about risk”.

Implications

As 2024 comes to a close, it is hard to escape the late 2021 vibes. Back then, liquidity was abundant, every wild startup was a unicorn, and SPACs were the new and improved way to raise capital. The market peaked just days before the year end.

Three quarters later, stocks had crashed, SPACs were dead, and every startup on the planet was running around trying (and mainly failing) to find new sources of funding.

This time around the election has been a big influence on markets but the flavor is the same as in 2021 — number go up. Stocks associated with Trump or his cohorts have done exceedingly well and cryptocurrencies have been on fire.

With sentiment and exposures at such high levels, however, there is a lot of room for disappointment. It may come out of nowhere like it did in 2022. At the time nobody had Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on their bingo card.

Disappointment could also come in the form of unmet expectations. As John Authers ($) wrote on Wednesday:

The question is whether the sentiment has gone too far. As others (for example, the New York Times) point out, Wall Street wants to accentuate the positive, assuming that the administration will go through with the policies it likes (tax cuts and deregulation) but not the ones it doesn’t (tariffs and ending the Fed’s independence).

This selective interpretation of likely policy moves and their impact is almost destined for failure.

Others think the bond market is the bomb waiting to go off, but for similar reasons. As Paulo Macro describes, either “tax cut extensions/new tax cuts for tips and manufacturers [are taken] off the table now, and risk assets derate” or they move ahead with the tax cuts/extensions “and watch the bond market go Full Liz Truss by the end of Q1 and take the cuts away…”

The challenge for policy to thread the needle without disrupting markets was also highlighted by Michael Howell. He noted, “His [Scott Bessent’s] ‘Triple-3’ policy hint to deal with escalating public debt reminds us of similar policies briefly attempted by short-lived British Prime Minister Liz Truss before the markets rejected her ‘pro-growth’ Budget (and her) in September 2022.”

With long US rates jumping up since the election, clearly others have similar concerns.

Many of the riskiest assets have performed extremely well since the election and have pulled stock indexes along with them. It may not make a lot of sense, but it sure is hard to get in front of that train, especially if you are managing against cap-weighted indexes. The new year will present a clean slate for a lot of investors and more information about policy initiatives. Perhaps the selloff from the FOMC meeting is an indicator of just how narrow the path is to meeting expectations.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.