Observations by David Robertson, 12/6/24

There was a lot of news this week but very little trading activity. Is it the calm before the storm? Let’s dig in.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

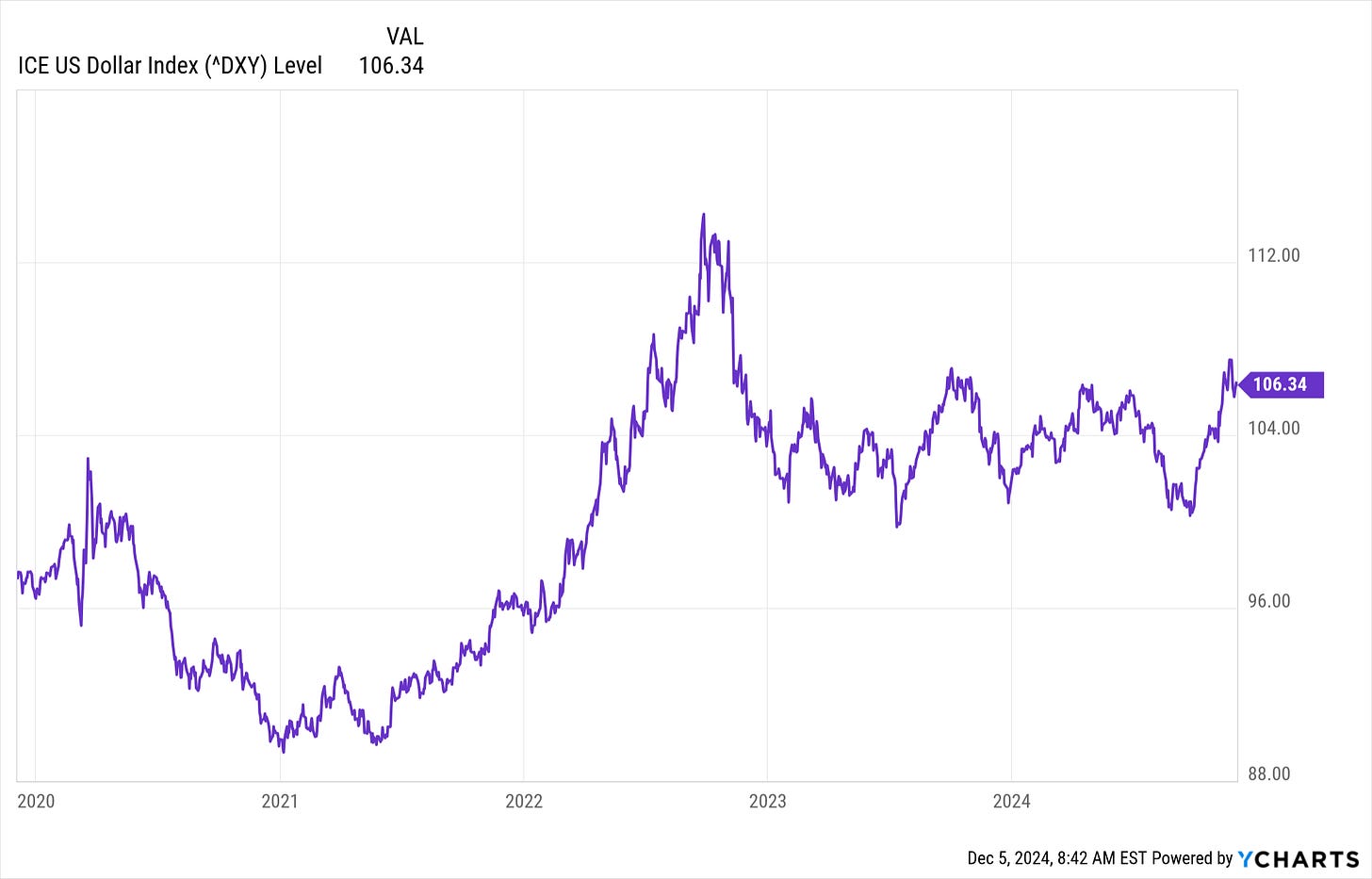

One of the more notable trends since the end of the third quarter has been the strength of the US dollar (USD). Several narratives have contributed to this including improving economic performance in the US, the expectation of higher tariffs under the incoming Trump administration, and emerging problems in several international markets. While continued strength in the dollar would be yet another unwanted challenge for foreign markets, USD has traded within a fairly well-defined range and is now at the top of it.

Speaking of currencies, another one that has been trending recently is the Chinese yuan. After showing a bit of strength in the fall, it has since weakened to its lowest levels in the last five years. Devaluation does not seem to be the top choice for China, but at the end of the day, it may not have much of a choice. Any devaluation of the yuan would deflationary elsewhere.

On a separate note, Robin Wigglesworth recently highlighted an article that illustrates two interesting phenomena. One is while public US companies can’t seem to go down, private companies are having a much harder time. Another is the private equity industry is up to its usual tricks - expressing supreme bullishness right up until the point of a complete writedown.

The FT article ($) notes, “Funds managed by Goldman Sachs will write off almost $900mn after Swedish battery maker Northvolt filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy this week … The losses mark a sharp contrast to a bullish prediction just seven months ago by one of the Goldman funds, which told investors that its investment in Northvolt was worth 4.29 times what it had paid for it, and that this would increase to six times by next year.” So much for bullish projections.

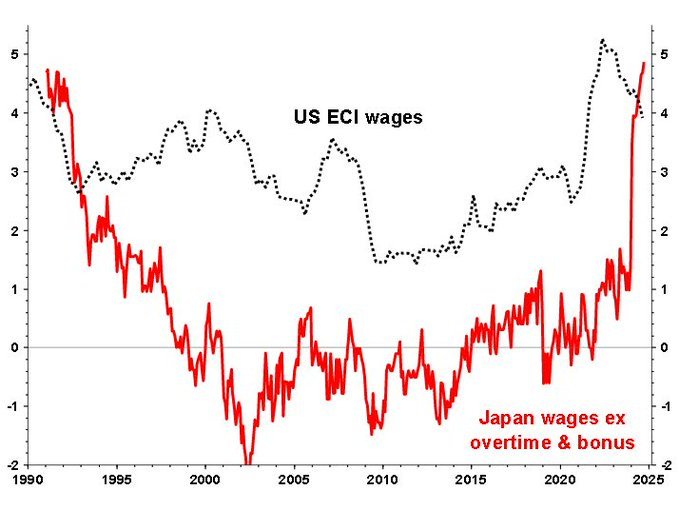

Albert Edwards provides a useful reminder that not all risks originate in the US. As he shows, underlying wage growth in Japan jolted higher in just the last few months. If this keeps up, Japan will be forced to either raise interest rates or otherwise defend its currency. That would cause a disruption in global capital flows.

Politics I

As commentators and investors alike try to read the tea leaves of what a new Trump administration will look like in terms of policy initiatives, it helps to take a step back and view the overall political landscape in perspective. This article by Jeremy Shapiro proved prescient about the election and as such also provides some insight on how to evaluate prospects going forward:

The problem for any candidate in this election is that voters desperately want change – they seem to hate the “system”, as well as almost all the institutions of civic life and, most of all, incumbent leaders. But majorities of voters also dislike nearly all specific changes. They don’t like immigration flows or immigration controls, tax hikes or deficit spending, intervention abroad or inactivity in the face of human rights abuses abroad. In this environment, vague vibes convey a sense of joy and optimism. Policy specifics seriously harsh that buzz. Precision just gives the opposition targets to attack.

Clearly, Trump benefited from the desire for change and the pushback against incumbent leaders. As I mentioned right after the election, this phenomenon was widespread across democratic elections this year - so it is not specifically a Trump or a US issue. Most importantly, campaigns based generally on change and vague promises were successful.

This creates an ominous backdrop for the next phase which is specific policy formulation and implementation. As Shapiro highlights, “Precision just gives the opposition targets to attack.” This is already happening as the majority of “voters also dislike nearly all specific changes”. While a lot of different things can happen, the political environment does not seem amenable to an ambitious reform agenda.

That leaves two general possibilities. One is that Trump goes ahead guns blazing with a major reform agenda which ruffles a lot of feathers and evokes a great deal of political backlash. The only question would be how long it could last before it became the target of anti-incumbency outrage.

Another possibility is that as grand plans collide head-on with political reality, they get modified substantially and become little more than small, incremental changes. In this case, big honking political conflict is avoided, but so too is the possibility of serious reform.

Importantly, neither of these possibilities is a smooth path to material improvement.

Public policy

Financial markets have continued to plough ahead on decent economic news and feel-good vibes that a Trump presidency will promote higher growth. The honeymoon period seems to be coming to a close, however, as increasing scrutiny is being placed on the policy ideas that are supposed to drive that higher growth.

Chris Whalen provided a good general description of the policy map laid out by the incoming Treasury Secretary:

Treasury Secretary-designate Scott Bessent earlier announced a "3-3-3" plan inspired by the late Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, which most resembles a policy proposal from President Joe Biden. Abe adopted a "three arrows" plan that featured aggressive monetary policy along with fiscal stimulus and structural reforms aimed at lifting Japan's economy from stagnation and persistent deflation.

One problem is these three arrows sound more like campaign promises than a workable policy construct. Whalen described Abe’s plan as a “dismal failure” and bets the Bessent plan “likewise will be a failure”. Andy Constan also chimed in: “I do know that the 3 arrows don't fly at once and can't fly together.”

Robert Armstrong at the FT ($) also highlighted the internal inconsistency of economic policy ideas that have been publicized:

It is hard to say how the Trump administration would respond to this trade-off [between reducing the trade deficit by reducing consumption and the fanciful notion such an adjustment can be made “entirely through the elimination of wasteful government spending”]. “The real question is, who drives policy? Is it Wall Street, or the people in the administration who want to revive the US economy?” asks Pettis. Facing a hostile market, Trump might retreat from structural reform, stick with cosmetic bilateral tariffs, and focus on other areas of policy. Or, in full populist mode, he might embrace the enmity of Wall Street, as Franklin Roosevelt did. I have no idea which is more likely.

One concrete example of the glaring inconsistency in the policy framework has already made headlines. According to the Clarion Ledger, “U.S. farm industry groups want President-elect Donald Trump to spare their sector from his promise of mass deportations …” Jim Chanos responded sarcastically, “We didn’t mean OUR illegal immigrants!” There is no clear indication yet where the line will be drawn on issues like this.

To that point, it is also not clear who will be driving policy either. The answer to this matters a lot as it will provide guidance as to how tradeoffs get made and how big of a reform agenda is pursued. As Ben Hunt points out, it is also entirely possible the whole idea of a “reform agenda” is just theater:

If the first order of business for ‘deficit reduction’ is tax cuts, because you know jOB cReAToRs or some similar supply-side bullshit narrative, then we’ll know it’s all just another oligarch scam.

So, one possibility is despite all the Sturm und Drang of populist reform, capital continues to win out at the expense of labor. Another, nearly opposite possibility, is that massive reforms are implemented that hurt in the short-term but help labor in the long-term. Yet another possibility is that whatever political capital currently exists rapidly evaporates and prevents the Trump administration from pursuing transformational initiatives.

In sum, there is an incredibly wide array of possible outcomes and the market is not discounting such a potential for failure. One way or another, it seems quite likely there will be disappointment.

Geopolitics

Just this week, the president of South Korea declared martial law and then revoked it six hours later and the government of France collapsed. While events like these are increasingly popping up in the news, there is little weight attached to them and virtually no market impact.

This is a mistake. Both events are indications of severe and unresolved political problems. As such, there will be more news coming. These aren’t events so much as points in a long and complicated process.

Back in January in the Outlook edition of Observations I wrote, “In addition [to the challenges in the US and China], there are a number of hotspots and proxy battles around the world. Putting all this together results in an unusually combustible mix.”

The events this week in South Korea and France are just the most recent reminders of the fraught geopolitical landscape. Investors would do well to keep this in mind when planning for the next year. There will be ramifications and they will be felt around the world.

Investment landscape I

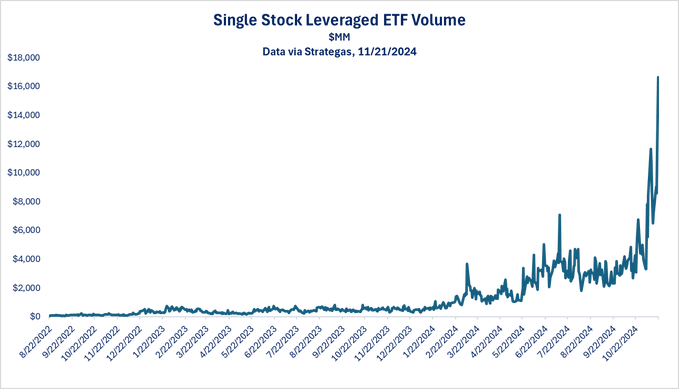

There are so many instances of wild and crazy action in the market week to week that it can be hard to single out just one. That said, the rapidly increasing use of leveraged single stock ETFs (exchange traded funds) does stand out for a number of reasons.

As Todd Sohn shows, single stock leveraged ETF volume has exploded in just the last few months.

This is notable for a couple of reasons. One is the ETF structure doesn’t technically provide any unique functionality. An investor can buy stocks on margin and accomplish the same thing. The ETF structure just makes it a little more convenient to gain leveraged access to single stocks.

Another item of note is the timing. As Jim Bianco points out, the parabolic move up really started a few months ago, just when the Fed started cutting rates.

As a result, while the Fed seems to be somberly contemplating academic models on where the neutral rate of interest is, the investing public is taking the signal to go gangbusters on stocks.

Bianco wonders rhetorically, “Is there a scenario that this does NOT end badly?” Personally, I sure don’t see how this can end well.

Investment landscape II

One of the messages I have repeatedly conveyed is that the stock market today is nothing like your father’s stock market or even the stock market you might have grown up with. A post from Dr_Gingerballs on X summarizes the evolution elegantly:

The stock market went from providing capital to grow, to providing liquidity to arbitrage, to becoming a universal retirement program, to becoming a casino. It’s hard to see it when everything is at ATHs, but our economy is fundamentally broken.

While Brent Donnelly focuses his attention more on crypto markets with his comments, they are still broadly applicable:

This is not a market in which CFAs will prosper. It’s a gambler’s and trader’s market and the options pricing is so demented you cannot possibly find positive EV trades buying vol.

Finally, Bob Elliott wins the prize for most succinct:

For decades prudence was a virtue in asset management.

These days it is a liability.

None of this is to say money can’t be made in the market or that all investors should completely avoid stocks. It does mean, however, that the way the stock market works and the risk/reward proposition embedded in current valuations makes it far less attractive for retirement and long-term savings purposes than it has probably ever been. Obviously this is something most long-term investors have an interest in paying attention to.

Investment landscape III

Consideration of the competition for title of “Most insanely stupid market activity” leaves one overwhelmed and awestruck by the sheer quantity of qualified candidates. As I have been reflecting on recent examples, I keep thinking back to the book, The Hour Between Dog and Wolf, by John Coates. As a former Wall Street trader turned neuroscientist, Coates is in a better position than almost anyone else to understand the relationship between markets and trader behavior.

For one, Coates recognizes the risk and reward potential of financial markets can create a potent allure for traders:

Normally stress is a nasty experience, but not at low levels. At low levels it thrills. A nonthreatening stressor or challenge, like a sporting match, a fast drive, or an exciting market, releases cortisol, and in combination with dopamine, one of the most addictive drugs known to the human brain, it delivers a narcotic hit, a rush, a flow that convinces traders there is no other job in the world.

For another, extended streaks, either winning or losing, cause fundamental changes in our physiology:

We are not built to handle such long-term disturbances to our biochemistry. Our defense reactions were designed to switch on in an emergency and then switch off after a matter of minutes or hours, a few days at the most. But an above-average win or loss in the markets, or an ongoing series of wins or losses, can change us, Jekyll-and-Hyde-like, beyond all recognition. On a winning streak we can become euphoric, and our appetite for risk expands so much that we turn manic, foolhardy and puffed up with self-importance.

Finally, those physiological changes also change our behavior:

When traders enjoy an extended winning streak they experience a high that is powerfully narcotic. This feeling, as overwhelming as passionate desire or wall-banging anger, is very difficult to control. Any trader knows the feeling, and we all fear its consequences. Under its influence we tend to feel invincible, and to put on such stupid trades, in such large size, that we end up losing more money on them than we made on the winning streak that kindled this feeling of omnipotence in the first place. It has to be understood that traders on a roll are traders under the influence of a drug that has the power to transform them into different people.

If you are anything like me, you find phrases like “manic”, “foolhardy”, “puffed up with self-importance”, “feeling invincible” and “putting on such stupid trades” to be unusually apt descriptors of behavior in the markets right now. This is useful. It means most of the trading action is not about fundamentals but rather about dopamine toxicity caused by an extended winning streak.

Implications

For several years I have highlighted the many influences that have artificially boosted share prices. Unusually easy monetary policy since the GFC, the migration from active to passive investing, the increase in share buybacks, and large and increasing fiscal deficits have all played a role in keeping the stock market on a roll.

Further, these factors have also created positive feedback loops that artificially magnify and extend the run. For example, as US stocks go up and become a bigger part of the global total, it causes increased flows from outside the US in order to maintain the global benchmark. There are others.

Now, yet another factor seems to be rearing its head and that is the euphoric feeling that often attends an extended winning streak. At very least, this is a plausible explanation for how “our appetite for risk expands so much that we turn manic, foolhardy and puffed up with self-importance.”

This leads to one of the most common questions of the day: “If stocks are so risky, when should I sell?” This is where Coates’ application of neuroscience is informative. Insofar as trader behavior looks a lot like the behavior of a drug addict, it is easier to see why the question is imponderable. It’s like asking, “What is the right amount of excessive drunkenness?” or “Exactly how high should one get on cocaine?”

One part of the reason why there is no specific answer is the effects of excessive alcohol consumption or drug consumption or winning trading streaks are different for different people and virtually impossible to judge for a group. Another reason is the risk of excess is extremely dependent on the context. Having a couple beers too many is a very different proposition on the living room couch than it is driving in heavy traffic.

But this is exactly where the mental model reveals its usefulness to investors. The goal should not be to test the absolute limits of an incredibly risky situation just to have a little more fun. Just like drunk drivers shouldn’t try to keep driving at full speed until just before they get into a big accident, investors shouldn’t try to remain over-exposed to risky assets until just before devastating, life-changing losses.

Of course, investors who have been riding large stock positions to new all-time highs are likely to be feeling the euphoria and invincibility of an extended winning streak. As a result, they are quite unlikely to change behavior until they go too far.

Other investors, including those who have been able to resist the intoxicating effects of an extended winning streak, can evaluate the investment environment with more perspective. While it can be frustrating to watch stocks continue to hit new highs on a regular basis, it is never a good idea to drop in on a party that has long since gotten out of hand.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.