Observations by David Robertson, 2/21/25

We got a break this week with no monumental news on Monday. Nonetheless, there is still plenty to figure out in this chaotic investment environment. Let’s dig in.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

In this environment of “flooding the zone” with news flow, it’s easy to lose track of things. Bruce Mehlman provides a great reminder that a government shutdown is imminent and seems likely at this point:

Any spending bill will need to find common ground among factions that fundamentally don’t agree: Fiscal Hawks, Defense Hawks, Border Hawks, Progressives, anti-DOGE Democrats (aka Democrats), representatives of states needing disaster relief and the White House.

Republicans are presently divided over how much spending to cut, whether and how to offset extending/expanding tax cuts & whether to waive the debt ceiling for 4 years. Democrats struggle over how to cut a spending deal that the White House/DOGE can’t just ignore by refusing to spend funds… and whether allowing a shutdown might play into GOP/DOGE hands, encouraging wider firings. Something’s gotta give.

While shutdowns in that past have had very little impact, this time could be different. For one, it is consistent with Trump’s narrative of trimming back government excess. For another, it would provide at least a cosmetic boost to cost saving goals. For yet another, an absence of federal employees keeping a watchful eye would facilitate even greater access for DOGE to penetrate government systems and gather information.

A shutdown for several days is inconvenient and/or bothersome for a lot of people, but ultimately not particularly meaningful. A shutdown for a much longer time could create a lot of havoc. Time to put this on the bingo card.

Inflation

Matt Klein ($) notes recent indications are that inflation is hanging around at a level slightly above target:

Whatever the exact reasons, the tighter conditions suggest that goods markets were already fragile to new supply shocks before any concerns about tariffs or other disruptions. That makes goods disinflation less likely, and should therefore be another source of persistent inflationary pressure relative to pre-pandemic conditions.

At the same time other indications are also pointing in that same direction. Growth out of Japan, for example, was solid in the last quarter of the year and its 10-year bond yield keeps going up.

In addition, while businesses with low income consumers are noticing signs of distress, a wide array of other companies still feel comfortable raising prices substantially. My recent experience was a 35% price increase for my tax return. It’s not hard to find lots of other examples. It sure doesn’t look like inflation is going away on its own.

Politics

Trumpflation is just beginning ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/61ae57ad-6ad2-4727-9849-9beca273c0d8

There is no doubt that Trump’s economic policies — or rather his instincts as far as we understand them — are bad for global economic prosperity and for US inflation. Tariffs and trade wars throw grit into the global trading system, preventing companies and countries from pursuing the most efficient outcomes. We all lose.

My warning relates to the scars I bear from Brexit. There is no doubt that the UK’s vote to leave the EU also damaged growth and raised prices. It prevented efficient outcomes, raised uncertainty, depressed investment and raised prices through a drop in sterling’s value.

The UK public now accept this to be true — nearly nine years later. But proving it in real time against a government determined to claim otherwise was all but impossible.

One of the lessons from Brexit is that political conditions often make it hard to persuasively differentiate good from bad economic policies before the fact: “You need to persuade people that outcomes are worse than an unknown world in which more sensible economic choices were taken. Even sophisticated people find counterfactuals difficult to comprehend and to explain.” In short, oftentimes, people just have to learn the hard way.

Unfortunately, situations like this usually ending up being a slow-motion train wreck. You can see exactly what is going to happen — and you can’t do anything about it. You just have to watch the tragedy unfold, slowly.

As bleak as that outlook is, it does provide useful insight. It suggests the recognizable harms will most likely play out. It suggests the realization of such harms will be a slow, drawn out process. It also suggests there will be an enormous amount of finger-pointing when things start going sideways. Not fun, but at least one can start planning for it.

Politics and public policy I

Speak Loudly and Carry a Big Salami ($)

https://thedispatch.com/newsletter/gfile/donald-trump-family-philosophy-mob/

I recently read this really interesting piece by John Ganz about how one of the most influential politicians in Trump’s life was Meade Esposito, the mobbed-up Democratic boss of Brooklyn, and de facto “shadow mayor” during the first Ed Koch administration. Esposito was a powerful ward heeler, but he was also an expert in pretending to be more powerful than he really was. Indeed, that’s kind of what made him so powerful—his ability to convince people he was more “connected” than he really was. Indeed, he got his start by fixing parking tickets for his “friends.” He wanted them to think he pulled strings in City Hall, but it turned out that he just paid the tickets with his own money.

Esposito was a close confidante of mobster Paul Vario, and would meet with the Lucchese family capo in private (Paul Sorvino’s character in Goodfellas is based on Vario). Esposito also worked closely with Trump’s father, Fred. And young Don saw Esposito’s “leadership” style—cursing, threatening, intimidating, but also generous to friends and allies—as the very definition of how strong, manly political leaders acted.

Which brings me back to Trump’s mafia-style foreign policy. How does a mob boss act? Well, in broad brushstrokes, he treats his enemies—or rivals—with respect. The heads of the five families are like little monarchs or feudal lords. On their turf, they have, well, sovereignty. You must ask for permission to do things in their territory or deal with people under their authority. Meanwhile, when it comes to people in your own organization or network or territory, you can do what you want, to one extent or another … The key is that your allies, friends, and normal citizens under your authority must show you deference and respect … It should be obedient and deferential.

Amidst a hoard of commentators purporting to have deep insight into President Trump’s decision making process, this background from Jonah Goldberg actually does provide some extremely useful insights into Trump’s worldview. In a convincing account, Goldberg describes the “mobbed-up Democratic boss of Brooklyn,” Meade Esposito, as a political role model for the young Trump.

I say “convincing” because it helps explain a lot of things. It helps “explain why he [Trump] thinks Russia and China deserve deference on their turf” — because rival “bosses” are viewed as “strong, manly, powerful” and therefore deserving of respect. It also helps explain why “he sees nothing wrong with belittling and intimidating allies” — because their role is to “show more deference to the head of the family.”

Insofar as this is a reasonably accurate depiction, there are some useful implications. First, while Trump’s worldview may seem wildly inappropriate to some, it is an “extremely familiar and natural way of seeing power, geopolitically and politically” in a broader context. Goldberg even emphasized, “until the Enlightenment it was simply the way politics worked—and it’s still the way politics works in much of the world.” In short, it’s not new. In fact, it’s probably fair to think of Trump’s political DNA as being a “Jurassic Park,” revived from times long past and “fit” only for a dramatically simpler environment.

Second, it is probably most effective to view Trump’s actions through the lens of such a tribal power model. For example, tariffs and threats of tariffs are not 4D chess, but as Ben Hunt puts it, just different forms of a protection racket. Similarly, offensive statements to allies aren’t bold diplomacy nearly as much as reflective of the expectation of obedience and deference.

Third, tribal power can be extremely effective in isolated conditions and even more so when social media can command the narrative. In a broader context, it becomes vulnerable to all the developments since the Enlightenment - things like “knowledge gained through rationalism and empiricism,” and “social ideas and political ideals such as natural law, liberty, and progress, toleration and fraternity, constitutional government, and the formal separation of church and state” (wikipedia).

While it is hard to predict how this will play out in the short-term, the longer arc of history suggests tribal power just moves humankind backwards.

Politics and public policy II

In addition to trying to understand Trump’s worldview, investors have also been scrambling to identify any kind of order to the wild array of executive orders issued to date. According to Jim Bianco in an interview on MacroVoices, there is indeed a plan/playbook, and it is detailed by Stephen Miran (and influenced by Zoltan Pozsar) in the paper, “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System”.

In my reading of the paper, I felt it fell far short of persuasive economic policy advice. For one, it misdiagnoses the root cause of trade deficits as being the strength of the US dollar. As I have posted many times, Michael Pettis has made it abundantly clear that the massive trade deficit with China originates with deficient demand in China to consume its own production.

For another, it relies heavily on the tariff experience of 2018-19 as a useful precedent for evaluating the consequences of tariffs going forward. That is a bad assumption, however, as the experience with Covid fundamentally reset inflation expectations after that. For example, I mentioned how Brent Donnelly explicitly recognized the change in inflation psychology in his evaluation of inflation in Observations 2/7/25.

Finally, and arguably most damagingly, Miran’s arguments for tariffs rely heavily on the assumption that meaningful concessions can be extracted from foreign central banks that hold US Treasuries as reserves. While there may be some capacity on that front since reserve managers are fairly insensitive to price, the proposition is fraught for two reasons.

One, reserves comprise only $3.8T of $8.5T of total foreign ownership of US Treasuries. Further, foreign reserve holdings comprise only $6.8T of total foreign ownership of $61.5T of US assets. In short, reserve holdings comprise only a small minority of foreign-owned US assets.

Two, as a general rule, autonomous foreign countries don’t like being bullied. Miran’s plan to strong-arm the small minority of foreign reserve holders runs the risk of compelling sales by the vast majority of foreign owners of US assets who are private.

As a result, it is hard to consider the Miran paper anything like a sold foundation for economic policy. Mostly, it sounds like pandering to Trump. In addition, virtually zero consideration is given to second- and third-order effects. Surely, there will be retaliation to excessive tariffs in one form or another. These are not cost-free propositions and it is not reasonable to expect substantive economic benefit from Miran’s “plan”.

What can be said is the notion of unilateral imposition of tariffs without consequence fits neatly into Goldberg’s “mafia rules” characterization. In that case, “when it comes to people in your own organization or network or territory, you can do what you want”. From this perspective, if you need to raise some revenue, it makes perfect sense to ask people in your sphere of influence to pony up a little more money (via tariffs).

Geopolitics

Of course, for other countries on the receiving end, such demands come across as an insult to their autonomy, a violation of past agreements, a form of extortion, and an overall insult. Indeed, these were the sentiments expressed by Eurozone leaders after JD Vance’s speech at the Munich Security Conference last week. Gideon Rachman ($) wrote in the FT:

The US vice-president told the assembled politicians and diplomats that free speech and democracy are under attack from European elites: “The threat I worry the most about vis-à-vis Europe is not Russia, it’s not China, it’s . . . the threat from within.”

If Vance hoped to persuade his audience, rather than simply insult it, he failed. Indeed, his speech backfired spectacularly, convincing many listeners that America itself is now a threat to Europe. In the throng outside the conference hall, a prominent German politician told me: “That was a direct assault on European democracy.” A senior diplomat said: “It’s very clear now, Europe is alone.” When I asked him if he now regarded the US as an adversary, he replied: “Yes.”

It’s hard to overstate the impression Vance made in Munich, and not in a good way. Rachman wrote, “What Vance did was to subvert the ideas of freedom, democracy and shared values that have underpinned the western alliance for 80 years” and concluded, “It is clear that the US can no longer be regarded as a reliable ally for the Europeans.”

John Authers ($) wrote in Bloomberg, “Such a speech has been unthinkable for the last 80 years, thanks to the trans-Atlantic alliance. Europe must now assume that that’s over. Even NATO itself is called into question.”

While the sense of shock still lingers, Europe is wasting no time. The response starts with Europe beginning “the painful process of ‘de-risking’ its relationship with the US”. While this will be challenging, Rachman calls out “that their freedom is now at stake”.

It’s hard to avoid the comparison to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. The type of seriousness and cohesiveness the Eurozone had failed to accomplish internally was accomplished almost instantaneously by Putin from the outside. Once again, but this time from the US, outside influences seem to be more effective at forcing tough decisions in the Eurozone than any internal force.

Investment landscape

Perhaps the most important call in the investment world right now is long-term interest rates — and the evidence is decidedly mixed.

For the time being, rates swing mostly on the assumption that economic growth is the primary driver of inflation and longer-term rates. If a growth number comes in strong, rates go up; if retail sales come in weak, like they did last week, rates go down.

If Trump’s policies slow down growth in the short-term, as it appears they will, this will eventually put downward pressure on yields. In addition, it also appears that the efforts of DOGE to reduce federal expenditures enjoys strong support, at least among Republicans, and that is probably helping to moderate yields as well.

Over a longer-term horizon, the calculus is different. On one hand Secretary Bessent has highlighted lower long-term rates as a priority. An important part of the path to get there is by sustainably reducing the fiscal deficit. As a result, progress on reducing the deficit is of paramount importance.

On the other hand, Bessent also inherited an extremely challenging situation. In addition to a large deficit (even more extraordinary given it has not happened because of a war), he also has a total debt that has too much short-term funding and a universe of Treasury buyers that (due to changing composition) is becoming increasingly price-sensitive. At the same time, longer-term yields in Germany and Japan are rising which makes them relatively more attractive.

Further, there are increasing signs inflation is picking up. Part of this is due to an economy that is still pretty strong. Increasingly, however, it is also due to signals that supply problems could re-emerge. Between a dwindling supply of labor due deportations and increasing frictions on global supply chains due to tariffs, inflation expectations have been rising steadily since shortly after the election.

Thus far, inflation expectations are still anchored fairly strongly to economic growth expectations. If and when supply constraints become a more visible threat to price pressures and/or weakness in demand for US Treasuries becomes a more visible threat to Treasury prices, longer-term yields could go up even if growth remains weak. Then we would have a whole new ballgame.

Investment landscape II

I don’t like including even more political content in the investment landscape section, but politics is driving the investment landscape right now. The following chart from The Daily Shot conveys some interesting insights:

It’s not surprising Republicans lean mostly favorable on Trump and Democrats most unfavorable, but the polarization is extreme. Democrats don’t register over single-digit approval on any of the items. As a result, none of the totals are even close to 50%. Despite good showings among Republicans, Trump has sharply divided the country and has precious little political capital to deploy.

It is also interesting to note how even the Republican approval levels for items like “picks good advisors”, “respects the country’s democratic values”, and “acts ethically in office” barely register over 50%. Apparently, such qualities are now viewed as acceptable costs to get your person into office rather than as “must haves”.

This dubious political landscape highlights the utility of a “fake it till you make” MO of a person like Meade Esposito (see “Politics and public policy I”). It also highlights the utility of narrative in defining and magnifying a public presence.

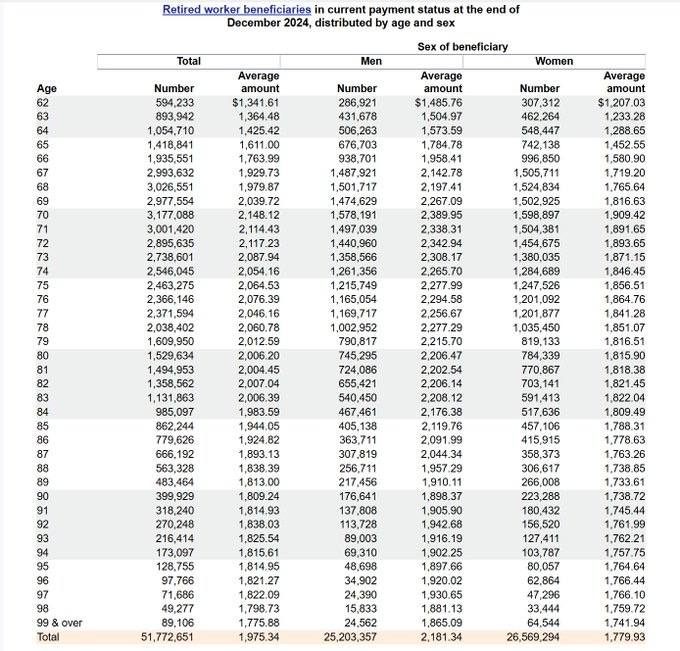

This helps explain why Elon Musk would suggest millions of dead people were receiving Social Security checks. Fortunately, James Surowiecki sets the record straight:

What's especially frustrating about Musk making it seem as if millions of Social Security checks might be going out to people aged 100+ is that we know how many Social Security checks went out in December to people aged 99+: 89,106.

The good news is there is precious little political capital to push things even further. The bad news is the Trump administration has every incentive to push as hard as possible to “fake it till they make it”. This is likely to get rough.

Implications

While the economic, political, and geopolitical environments are being seriously disrupted, the market remains eerily calm. Long-term rates are a linchpin in holding this paradox together.

Thus far, concerns about growth have also translated directly into lower expectations for inflation. However, if markets start sniffing the potential for both lower growth AND higher inflation, i.e., stagflation, a significant hurdle will have been crossed and stocks would be extremely vulnerable.

Alternatively, stocks could also suffer from a change in narrative on the political front rather than the economic one. For the first month, sentiment and support remained strong. This past week, however, it felt like the narrative was changing. Republican lawmakers are being showered with vitriol from constituents who have lost their jobs or have been otherwise disrupted. Global opinion of the US has fallen hard and fast. In addition, the Trump administration seems to have shifted gears from “fast and furious” to ordinary pandering. There is a sense political capital is already fading.

The odds against success for the Trump administration are high, as are the odds of overreach. It very much feels like we are driving toward a “Thelma and Louise” moment with both our government and our economy. As discomfiting as that sounds, it is exactly such “emergency” situations that provide politicians the opportunity to grab even more power to “fix” the problem.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.