Observations by David Robertson, 4/19/24

With markets being shaken from the launch of attacks on Israel from Iran last weekend, it’s a good opportunity to spend some extra time on geopolitics this week. Let’s take a look.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

The equity rally is on pause ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/f38a3165-268b-4810-a417-42f23eb6772b

On or around March 20, the stock market stopped rising and started moving sideways. This chart goes back to when the rally began, last October:

Since then [the March 20 FOMC meeting], assorted things have happened to suggest that we might not be living in that best of all possible worlds. On April 1, an inauspicious date, Israel bombed the Iranian consulate in Damascus, which has nudged oil, already rising, a bit higher (see next item). The next day, Tesla, its membership in the Mag Seven already tenuous, reported sharply declining unit sales. April 10: another uncomfortably spicy CPI report. On the 12th, JPMorgan Chase, the most important bank in the world, disappointed the market with its outlook for lending margins, and the shares fell. Then, yesterday, a blowout retail sales report confirmed the idea that the economy was running hot, and the market did not like it at all.

There are two good points here. One is the tone of the market definitely changed some time late in March. A second is the news highlights since then have been extremely varied. The notion of any kind of smooth and easy path forward is falling apart rapidly.

Two other phenomena that have coincided with that time frame are the rapid rise in 10-year Treasury yields and the rapid runup in the price of gold.

Bob Elliott put out a nice thread on these topics and concluded: “With pressures still firmly in place for US rates to push higher (decent US growth, inflation still not at target, Fed holding for longer, and much higher Q2 supply) the global ripples of higher yields are set to continue.” Well put.

Economy

Consumers on the Couch ($)

Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, APRIL 12, 2024

“The Cost of Money Is Part of the Cost of Living: New Evidence on the Consumer Sentiment Anomaly,” a scholarly paper published in February by the National Bureau of Economic Research, examines the source of the paradoxical detachment of consumer sentiment, which registered 79.4 on the University of Michigan survey (down from 101 on the eve of the pandemic), from GDP growth, which, in the fourth quarter, printed at an annual rate of 3.4%.

The authors’ search leads them to a 1983 overhaul of the Consumer Price Index that eliminated interest expense from the cost of living. Add it back, and today’s inflation data look more like the double-digit shockers that may have cost President Jimmy Carter the White House in 1980.

Why Have Rate Hikes Not Done Anything? ($)

https://theovershoot.co/p/why-have-rate-hikes-not-done-anything

American companies and consumers have cut their borrowing in response to higher interest rates, but this has not affected their actual spending. The result is that the U.S. economy is still continuing to grow briskly in both real and nominal terms despite years of allegedly “tight monetary policy”.

The explanation seems to be twofold. First, borrowing has not been that important ever since global financial crisis, which limited the impact of any negative credit impulse. Instead, spending has been financed overwhelmingly out of income growth, which continues to be faster than before the pandemic. At the same time, healthy balance sheets—both in terms of lower indebtedness and persistently higher holdings of cash and equivalents—make it easier for businesses and households to look through any temporary income volatility and keep spending.

The economy continues to confound. On one hand, all kinds of indications of consumer financial distress are emerging and complaints about inflation are getting louder again. On the other hand, spending in aggregate continues apace and on things like airline travel and foreign vacations that are clearly discretionary. What gives?

The first set of quotes from Grant’s reveals an interesting tidbit of which I was previously unaware: Interest expense is no longer included in the cost of living used to determine the Consumer Price Index (CPI). This answers part of the conundrum. A good part of consumer financial distress is being caused by higher interest rates - which does not show up in the CPI.

This has a couple of important consequences. One is that consumers who have a significant amount of debt that is subject to short-term rates is experiencing a much higher level of inflation than others and a much higher level than is being reported. This creates deceptive signals for economic policy and fuels political discontent.

The second set of quotes from Matthew Klein targets another part of the conundrum which I have addressed before: “[Consumer] spending has been financed overwhelmingly out of income growth, which continues to be faster than before the pandemic.”

This is perfectly reasonable and makes perfect sense. It only creates some dissonance relative to the last major instance of consumer distress which happened during the GFC. Household balance sheets at that time though were more leveraged and real wages were essentially flat.

From a high level, then, the economy is probably doing better than a lot of measures of consumer distress indicate. Those measures are right, but they aren’t as important to the overall spending pattern as they used to be. At least as important are the political implications. Consumers with significant debt burdens are de facto becoming an economic underclass. Worse, their travails aren’t even officially recognized by the inflation data. That is likely to cause political consequences.

Japan

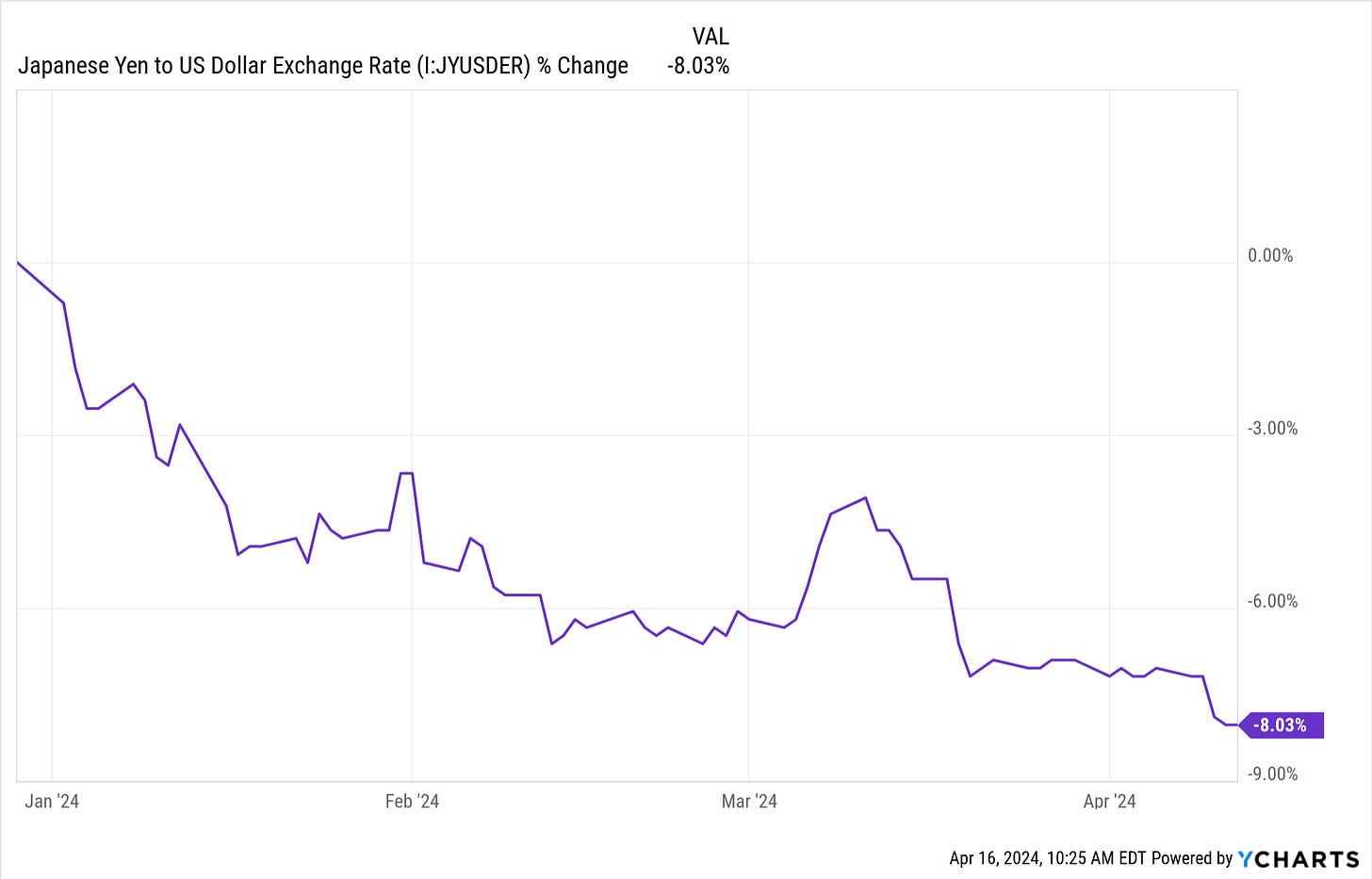

Five week ago ago I discussed the upcoming possibility the Bank of Japan (BOJ) might raise rates out of negative territory, which it did the following week. I also described the occasion as a “big deal”. I still think it was a big deal, but not for exactly the same reasons I thought.

At the time, I thought crossing the threshold into positive rates would make “further hikes easier”. While this is true and a nontrivial point, markets have indicated this possibility is unlikely by selling off the yen (in dollar terms).

A good chunk of this was probably due to incremental strength in the US dollar, so it’s important to not read too much into the move. Some of the move may relate to the Chinese yuan as well. Nonetheless, the yen cruised through the 152 USD/JPY threshold at which interventions have been targeted in the past.

One explanation I found especially insightful was the scenario laid out by Michael Kao in his Substack post ($), “The Battle of the BADS”. In his view Japan faces a decision between two bad choices, either defending JGBs (Japanese Government Bonds) or JPY (the yen exchange rate). Between these two bad choices, Kao thinks allowing JPY to weaken is the less bad choice. Apparently, that is what the market is beginning to accept as well.

The reason this is still a big deal is it formalizes the tradeoff between JGBs and the currency. In other words, the BOJ is tacitly admitting yield curve control (YCC) is effectively permanent policy. That means interest rates will likely remain below inflation which means bonds will be extremely unattractive investments. In a world of excessive debt, this is an important milestone.

Geopolitics I

Following Treasury Secretary Yellen’s six day trip to China and a weekend of fireworks between Israel and Iran, geopolitics has been in the news more often than usual. What is also happening more often than usual is the escalation of conflict to the point where serious consequences can arise.

By many accounts, this appeared to be something more than a normal diplomatic tour. As Shannon Brandao ($) reported, Yellen issued warnings to Chinese companies against supporting Russia’s war effort and singled out banks for special attention.

Yellen’s remarks came after “secretary of state Antony Blinken told EU and Nato foreign ministers that Beijing was assisting Moscow ‘at a concerning scale’, and providing ‘tools, inputs and technical expertise’,” according to the FT. Observers commented, “The warnings were explicit,” and noted, “There has been a shift and it was felt in the room . . . this was a new development. It was very striking.”

As if to punctuate the trip, Russia’s foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, appeared in China immediately after Yellen left to highlight the ties between Russia and China.

The main point is while geopolitics has been easy to fade in terms of impact on markets, that may be changing. The reason is key elements of the geopolitical construct have been unsustainable. Primarily, the US can’t afford to be the global cop nor can it afford to buy ever-increasing quantities of Chinese exports. On the other hand, neither China nor Russia want the US to dictate economic, financial, legal, or any other terms.

As a result, it looks like the most likely way to establish more sustainable conditions will have to be through force. In this context, Yellen’s trip looks more like it was intended to define the contours of conflict rather than to avoid conflict altogether.

Geopolitics II

Investors continue to grapple with the trajectory of inflation (and therefore monetary policy) and the pattern of increasingly frequent geopolitical flare ups. Judging by rising volatility, there seems to be increasingly uncertainty in regard to asset prices. As I discussed in the quarterly blog post, the key is recognizing these two important drivers as being interrelated and not primarily distinct forces.

With the benefit of hindsight and some perspective, it is easier to recognize that the very nature of geopolitical conflict has fundamentally changed. Under the neoliberal order the main credo was “live and let live”. Conflicts were limited and/or kept at the periphery of major powers because it was in everyone’s interest that it be so.

In more recent years, however, the costs and benefits of the neoliberal system have become less advantageous to each of the main powers. China wants to be free of the constraints of the US dollar-based financial system and the US can no longer afford to absorb all of the manufacturing excess China’s imbalanced economic model exports elsewhere.

Since there really is not a path to a mutually agreeable resolution, this means differences will have to be resolved through brute force. This means the very nature of geopolitical conflict has changed.

In handicapping the contest, the US has a number of advantages. It is the incumbent power, controls the global financial system, is the pre-eminent military power, and is mostly resource independent, among a long list of other advantages.

That said, China is also a formidable power and is not about to give in easily. As Louis Gave pointed out (in comments posted by PauloMacro ($)): “I don’t think foreigners get Xi’s desire to be a ‘great power’ once again … But you can’t be a great power with a weak currency. And you definitely can NOT be a great power if you settle your trade in your rival power’s currency.” He concludes, “Xi is playing for keeps. He will impose all the pain in the world on the Chinese economy before devaluing meaningfully.”

A very different perspective of the Chinese situation was provided by Russell Napier who claims, “The time has come for the Chinese authorities to take the monetary levers to generate higher nominal GDP growth. This means allowing the exchange rate to adjust to the level of broad money growth necessary to reduce China’s burden. The current international monetary system ends when China assumes this full monetary independence.”

Regardless of the specific outcome, the ongoing struggle between the US and China is likely to look like a heavyweight slugfest and will influence financial assets for its duration.

Investment landscape I

The People’s Choice ($)

Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, APRIL 12, 2024

“And now,” [Lacy] Hunt recently told the host of the Hidden Forces podcast, Demetri Kofinas, “we have a condition of negative national savings. Without net national savings, we cannot have net physical investment. Without net physical investment, we cannot increase the capital stock.”

Net negative savings is no everyday occurrence. Prior to 2023, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis identifies only seven prior examples since 1929. Each was a period that most Americans would probably not care to relive: 1931–34 and 2008–10. Last year was the only one of the seven that was not the occasion of, or in close proximity to, a major slump.

The comments above by Lacy Hunt and Jim Grant expose some hard truths about the economic and financial landscape in the US. In effect, the country is currently being run like a self-liquidating investment vehicle: It keeps paying dividends greater than its earning capacity.

One point is the threshold of net negative savings has only been breached in the past during times of great turmoil such as the Great Depression and the Great Financial Crisis. Another point is the problem has been developing for years. Nine years ago John Hussman characterized the nature of our economic policies as “Eating our Seed Corn”.

In that piece, he said, “The U.S. has become a nation preoccupied with consumption over investment; outsourcing its jobs, hollowing out its middle class, and accumulating increasing debt burdens to do so.”

He also suggested, “What raises both real wages and employment simultaneously is economic policy that focuses on productive investment – both public and private” and recommended, “What our nation needs most is to adopt fiscal policies that direct our seed corn to productive soil, and to reject increasingly arbitrary monetary policies that encourage the nation to focus on what is paper instead of what is real.”

Fair enough. What won’t work is monetary policy. Hunt explains, “You can increase the money supply, but that will just have an inflationary effect. There’s no way to inflate our way out of the problem.” He concluded, “What you’re basically doing is, you’re using your depreciation to live on.”

So, that’s the economic theory and it is useful so far as it goes. It describes the nature and magnitude of the economic dilemma. What it does not do is provide useful guidance as to public policy direction. The reason is rebalancing the economy will be too disruptive to consumer spending and financial asset values, and therefore too unpalatable politically, to implement directly or comprehensively.

Rather, what is most likely to happen is for politicians to take a longer, more circuitous route to greater economic investment. Most likely that will involve inflation not because it solves the problem but because it buys time. As that plays out, don’t be surprised by the typical ingredients of such a transition which include even nastier political squabbles, dramatic political realignments, and geopolitical conflict.

Investment landscape II

One thing the recent fusion of economic and geopolitical surprises has accomplished is to increase volatility. The VIX volatility index for stocks picked up notably at the beginning of April and the MOVE volatility index for bonds started pushing higher in late March.

This increase in volatility has coincided with higher yields (and therefore lower prices) in bonds to create a double-edged impact on liquidity. Lower prices reduce the amount of collateral available for borrowing and higher volatility reduces the capacity of each dollar of collateral. Michael Howell highlighted the dynamic in a recent post on X, “Latest weekly track of collateral pool highlights sideways drift (as bonds sell-off) and limits future near-term growth in Global #Liquidity”.

In addition, the background of higher volatility could make earnings season more interesting than usual. With expectations exceedingly high and companies already reporting record high margins, there is plenty of opportunity for itchy trigger fingers to cause big selloffs in cases where expectations are not met.

How long is this higher level of volatility likely to last? That’s hard to say, but it’s easy to see that geopolitical tensions and bothersome inflation data have been important contributors to the growing sense of discomfort.

Finally, higher volatility may very well serve policy purposes at the time as well. Allowing some of the exuberance to dissipate from the stock market eases inflationary pressures without forcing such visible action as raising rates. Further, allowing stock prices to recede a bit in the context of extremely high exposure also reduces the risk of severe market dislocations.

Mainly, the higher volatility seems to be serving the purpose of warning market participants to hold back on their most aggressive tendencies.

Implications

The fundamental change in the nature of geopolitical conflict to a more adversarial relationship between China and the US clearly has implications for financial assets. Most obviously, the ongoing and evolving conflict creates a higher baseline level of uncertainty - which is obviously bad for financial assets.

Some implications, however, are not as intuitive. For one, geopolitical priorities trump all others in the hierarchy of government policy needs. This means when push comes to shove, policies that serve a useful purpose in terms of domestic conditions may be paused, altered, or even terminated if they come into conflict with broader geopolitical goals.

Not only can financial conditions be driven more by geopolitical considerations than domestic economic ones, but the impetus for changes can easily originate outside of the US. All this makes the investment landscape increasingly treacherous.

As Russell Napier highlights in the FT this week: “Developed world authorities are already being drawn into greater interventionism to ensure that the gross imbalances of the old monetary system (primarily excessive debt levels), are unwound with minimal sociopolitical dislocation. This new global monetary system brings radical challenges for investors which they are ill-equipped to navigate without a deep understanding of financial history.”

So, a lot more interventionism and financial history as a guide. That’s a very different playbook than most investors are currently equipped with.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.