Observations by David Robertson, 6/30/23

The S&P 500 has been bouncing around for almost three weeks with little to show for it. As Tom Petty sang out, “The waiting is the hardest part”. It seems like the market waiting for something - but what? And when will it happen?

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

While Europeans have been regaling the fact their economies did not implode over the winter from high energy prices, the graph below from @SoberLook suggests the celebrations may have started too early.

Not only are signs of persistent inflation emerging, but other negative economic surprises are also accumulating. If the current disparity in economic performance continues, one would expect the US dollar (USD) to perform well against the Euro.

In regard to economic news, Jim Bianco posted a chart that speaks a thousand words.

As he puts it, the biggest determinant of one’s opinion of the economy is “The political party of the resident of the White House and what you think about that”. One’s perception of the economy seems to have virtually nothing to do with what is actually happening in the economy.

Bianco claims this evidence renders economic opinion polls useless. While I agree with his conclusion in regard to economic conditions, I think he understates the overall usefulness. After all, it is not a trivial thing to know that a large proportion of workers and consumers view the world solely through the lens of political beliefs, rather than making any kind of attempt at evaluating evidence. The word “ungovernable” comes to mind.

Politics

THE GRANT WILLIAMS PODCAST: MATT STOLLER ($)

https://www.grant-williams.com/podcast/the-grant-williams-podcast-matt-stoller/

There’s a lot of fights over corporate power right now. I think what’s happened is traditionally corporate power and economic power has not been the center of politics for the last 40 years. It actually was the center of American politics, I think from the 1770s until the 1970s. Frederick Douglass used to talk about the land monopoly as fostering slavery. You can find arguments about monopoly. It really was one of the two key dominant traditions in America was anti-monopoly.

First of all, I work with populists on the right. It’s very easy to work with... If you’re a democrat banking lobbyist and you work with a Republican banking lobbyist, no one’s going to be like, “How dare you?” That’s the thing. I just work with Republican populists who are skeptical of corporate power. And since nobody pays me to do that, I’m not working for a big corporation and neither are they, part of the culture war is designed to get people who do agree on very basic questions of economic power to not talk to each other.

One of the themes that comes out of this conversation with Matt Stoller is a fresh appreciation of how pervasive the negative influence of corporate power has become in our lives. We experience it so frequently we barely even notice it any more. A recent tweet by Stoller highlights the particular case of Amazon and its Prime cancellation process:

The Iliad Flow [Amazon actually named the cancellation process] required consumers intending to cancel to navigate a four-page, six-click, fifteen-option cancellation process. In contrast, customers could enroll in Prime with one or two clicks

As Stoller also highlights in the thread, “Amazon routinely lied to government investigators and withheld relevant information it had promised to turn over.” Apparently just another day at the office screwing over consumers with impunity.

Another theme, and I believe an increasingly important one, is the movement against corporate power is becoming a bipartisan one. It is important because it is a political issue that can transcend culture wars.

As the Economist points out ($), Joe Biden’s administration has made “fighting corporate concentration” a priority. It has done so by appointing Lina Khan, by issuing “an executive order calling on agencies across government to focus on competition”, and by appointing “Jonathan Kanter, a lawyer who had worked against Google, to lead the antitrust division at the Department of Justice (DOJ).”

In addition, Tim Wu, of Columbia Law School, who the Economist reports, “worked in the White House on competition policy,” says of the Democratic focus on antitrust, “We’re in year two,” suggesting only the beginning of a larger project.

Wu also highlights the increasingly bipartisan nature of the effort: “The politics of this [antitrust] have changed, and no one wants to be on the other side of it”. Increasingly, “Bashing big business has become more common among populist Republicans”.

In an era of hyper-partisan politics, who would have guessed there is an issue both sides agree on? While it is fair to be skeptical of how much of these efforts will ever reach the point of seriously hurting large companies, it is also fair to say the political tides are turning against corporate power.

Ethics

From Ben Hunt’s Twitter thread on June 21:

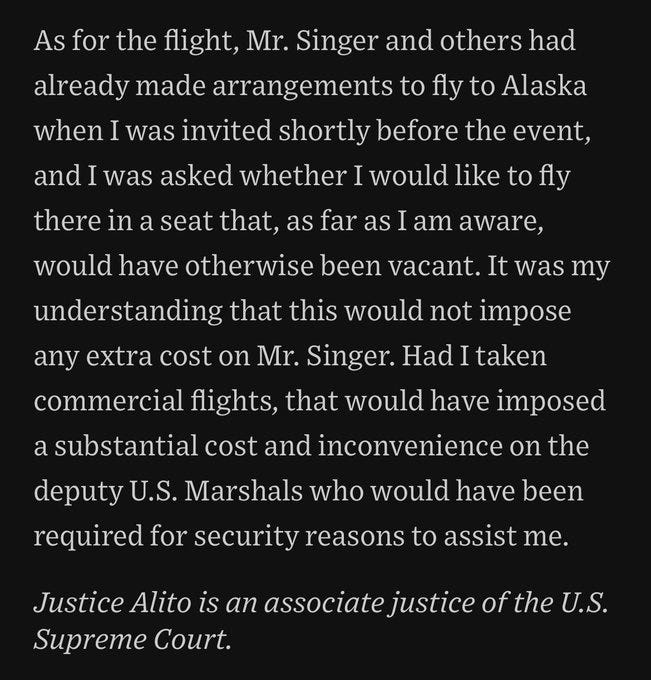

LOL. “Paul Singer’s jet was going to Alaska with or without me, so really there was no value associated with my flight.”

If a junior analyst at a public pension fund did this, she’d be fired immediately.

There are plenty of examples like this from both political “sides” so the point here is not a partisan one. In fact, it is a distinctly non-partisan one: There are far too many people in positions of power who don’t even make a modest effort to avoid impropriety, let alone the appearance of impropriety. Nope, they crouch down and make bounding leaps over the lines of propriety the rest of us need to abide by.

I’m sure I’m not the only one who finds such behavior disgusting. I’m also sure I’m not the only one who has read or heard of so many similar instances as to have become almost completely inured to them. Serious question: How much longer can people in power act as if rules and ethics don’t apply to them without some kind of retribution? When will people get sick enough of it to do something about it? What will society look like after that happens?

Inflation

Waiting for the Godot Recession ($)

Central banks are going through a tough time. We already knew that they were no longer in confident control of inflation, and that their entire status was coming under increasing political attack. Now, a survey appropriately entitled Under Pressure reveals that even the central banks’ own reserve managers don’t think they can get inflation under control any time soon. And last year’s implosion of asset prices seems to have cost them about $725 billion.

The finding that will be most painful for monetary policymakers concerns inflation predictions. Essentially, OMFIF found no reserve managers at all who would sign up to the notion that inflation will return below 2% within the next two years, with many expecting it will be far higher:

One key party whose opinion on inflation has been neglected is that of central bank reserve managers. Apparently, according to a recent survey, a grand total of zero of them think inflation in major economies will fall below 2% in the next 12-24 months. About half vote for 2-4% and another half vote for 4-6%.

This is a striking divergence from “the current two-year breakeven rate of inflation for the US … [which] is only 2.02%”. Clearly, the central bankers see something on the inflation horizon that traders do not see - or don’t yet care about. That seems to be a very significant difference of opinion from a source that just might have some proprietary insight on the subject.

Monetary policy I

While most investors still seem to be evaluating monetary policy based on reactions to economic and financial data, I continue to believe monetary policy actions are best explained as being part of a broader plan. The plan, as I see it, has three steps.

The first step is to sustainably raise short-term interest rates. One major policy goal (in addition to fighting inflation) is to constrain the asset-backed lending industry. In doing so, the Fed will also regain a great deal of control over money supply. Another major policy goal is to reset rates to a level that is much more conducive to productive investment. Finally, higher rates also provide a disincentive for increasing debt too quickly.

The second step, according to my hypothesis, will entail a managed effort to allow long-term rates to increase. This could be done by increasing the proportion of overall Treasury funding through longer-term bonds. The Fed could also get involved by increasing QT and/or by selling down its mortgage-backed security (MBS) portfolio. The policy goal would be partly to establish a more favorable yield curve such that banks can rebuild capital and another goal would be to finally transmit policy tightness to risk assets as part of a policy of “controlled demolition”.

Higher short- and long-term rates will quickly manifest in rapidly rising interest costs in the fiscal budget. In my view, this striking reality will be used to finally force the country to address the problem of excessive spending. Of course, lower fiscal spending will not be enough to manage the debt levels - so financial repression will also be required. This will involve suppressing long-term rates below inflation for an extended period of time.

Can this plan go wrong? Absolutely. Can big mistakes be made along the way? No doubt. Can unforeseen events blow the plan up? Yes.

Even with all these caveats, however, the evidence from actions already taken and the patterns of history suggest this is a good baseline outlook. It is also one that has very serious implications for financial assets and conventional asset allocation.

Monetary policy II

The return of quantitative easing ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/6d14cad1-00f2-4d39-969f-c01ae1860d34

In short, markets need ever more central bank liquidity for financial stability and governments will need it even more for fiscal stability. In a world of excessive debt, large central bank balance sheets are a necessity. So, forget QT, quantitative easing is coming back. The pool of global liquidity — which we estimate to be about $170tn — is not going to shrink significantly any time soon.

I admit to being a fan of Michael Howell, at least partly due to his outstanding book, Capital Wars. He clearly understands the key mechanisms of a global financial system inundated with debt: Huge quantities of debt need to be refinanced on a regular basis. This reality explains much of what happened after the GFC.

Times have changed, however, and it does not appear to me as if his worldview has changed with them. Pardon the pun, but he seems to be fighting the last war. He seems to assume all debt must be rolled over or financial instability will ensue - like in the GFC. I don’t believe this to be true. Nor, from what I can tell, does the Biden administration believe it to be true either.

As I highlighted in the 5/5/23 Observations, Jake Sullivan’s April Brookings speech laid out a number of important public policy priorities. Notably, among them, he recognized “a new environment defined by geopolitical and security competition, with important economic impacts”. This “new environment” also involves rebuilding an industrial base that has been “hollowed out”. Further, the policy statement recognizes “the challenge of inequality and its damage to democracy”.

Importantly, each of these policy priorities are consistent with higher rates. As a result, I think it is pretty clear the Biden administration is prioritizing different things than Michael Howell is. Even more to the point, I would suggest this new industrial policy differentiates between good debt and bad debt. Good debt is for productive economic capacity. Bad debt is for financial engineering. More of the former, less of the latter.

As such, there seems to be appetite for letting the unproductive debt go, i.e., default. As a reminder, this is what happened in the GFC. Lots of shadow banking efforts fell apart under the strain of falling asset values. This caused a contagion that proved virtually impossible to control.

This time is different in that the impetus for adversity is rising rates, not declining asset values. It is also different in that authorities have a better understanding of the shadow banking businesses and have worked to provide more policy levers in order to effect a “controlled demolition”.

In the context of this interpretation, then, modestly improved liquidity is not a signal of a turning tide, as Howell describes, but rather a reflection of a bigger set of policy tools to manage the demolition (of undesired debt).

In sum, I respect Howell’s view enough to consider it seriously as a possible scenario. In this case, though, I think he is over-emphasizing an old playbook and under-emphasizing new policy priorities. We’ll see. If he’s right, stocks could levitate further. If I’m right, stocks are about to take a dive.

Landscape

Two articles in Tuesday’s FT caught my eye, mainly for the common theme in two different industries. The first detailed commercial real estate entering a “sombre phase” ($).

A long-anticipated reckoning is under way in the US commercial property industry, with the results playing out at 529 Fifth and other addresses. Sharply rising rates, a regional banking crisis that curtailed credit and a trend towards remote work are all wreaking havoc. Older office buildings have borne the brunt, but other real estate categories have not been spared.

“I am not sure people have come to terms with how long the storm will hover and how much damage it will do,” said Scott Rechler, president of RXR, one of New York’s largest developers, likening the situation to a hurricane making landfall. “As for multifamily and other [commercial real estate], I believe that the markets are underestimating its potential severity.”

One broker estimated that only the top 10 per cent of office buildings in New York were not distressed — either in terms of the level of debt or occupancy. “I think we are on the front edge of the forced sales,” this person said.

A second article focused on the venture capital industry ($). The conditions are extremely similar:

Clear evidence of just how tough venture capital land is getting emerged this month with setbacks for two firms in the sector. After nearly a year of marketing new, multibillion-dollar funds, Insight Partners and Tiger Global have failed to reach anywhere near their targets. Following an already dismal year, it was a painful augury for venture capital and start-ups. As one Silicon Valley veteran put it: “It was the first real sign that existing investors are saying, ‘No más’.”

There will be a bloodbath of “down rounds” — where valuations fall in a fundraising — and insolvencies.

A discrepancy in price between what a seller of shares wants and how much an investor is willing to pay has dramatically narrowed — the “bid-ask spread” has gone from 44 per cent to 17 per cent, according to Carta — suggesting that sellers are far more willing to accept heavy discounts than a year ago.

Both industries thrived on ridiculously cheap capital. Both industries hit a wall when the cost of capital went up. Both industries have managed to tread water for several quarters despite adverse conditions. Both industries have pressed on with little more than a wing and a prayer. Both industries are now beginning to crack under the pressure.

Whether it be distressed real estate on the “front edge of the forced sales” or venture capital investors saying “no mas”, the challenges are becoming quite real. A year ago it was possible for owners to pass this off as a bump in the road. Now, sellers are gradually coming to accept the reality.

One point is much of the value destruction that has occurred is going to start getting recognized soon. That will ripple through the industries by setting prices lower and by destroying capital in the process.

Another point is this normalization process is likely to continue for years. The problems run deep, the capital raising environment changed quickly, and these are mostly long duration assets. As one CIO framed it, “Office is in the middle of a massive paradigm shift. We think it is going to take five-plus years to work out the fundamental shift in demand”.

Implications

I’ve talked several times about the pattern of policymakers becoming more proactive. In doing so, I normally highlight the implication that investors can get a better take on monetary policy by incorporating a perspective of proactive, rather than reactive, policy making. The general idea is it is more useful to follow the basic contours of a plan than it is to keep justifying why expectations were not met. Having some conception of a policy plan is equivalent to having a “prepared mind”.

The slightly deeper implication is that it is helpful for investors to be proactive as well. The best way to test out various possible policy scenarios is to envision different economic, financial, and political states that might require policy intervention.

I think this is exactly where many investment views diverge. In a very broad generalization, I think it is fair to say older investors are more satisfied with the way things are (and have been) and younger investors generally feel the existing system does not work for them and believe major changes need to be made. Even though I am not young, I tend to fall in the latter camp; I do not believe the old trajectory is sustainable.

The major implication, then, is that sooner or later, there will be major changes in social mores and institutions. Further, when things do change, they can change quickly. After all, most people already know the existing flaws; they are ready for change. While there may be some upheaval in the process, ultimately the refresh will prove good and necessary.

With this very big picture scenario in mind, we can also incorporate implications from the three phases monetary policy I envision. In the first phase, while short-term rates are raised to sustainably higher levels, the main victims will be businesses that depend on cheap, short-term financing. Asset-backed lending will be hit hard, but commercial real estate, private equity, and venture capital will also be hit hard. The main street economy will prove surprisingly resilient.

The second phase of monetary policy involves allowing long-term rates to rise. This will crush valuations of risk assets. Conversely, better lending spreads will help bank profits and higher long-term rates will provide much better incentives for industrial companies to invest in productive capacity.

Finally, long-term rates cannot be allowed to stay too high for too long, lest interest payments completely consume the fiscal budget. As a result, I ultimately expect some form of financial repression to be imposed in order to keep long-term rates below inflation so as to inflate excessive debt away. This is when hard core inflation plays such as gold and commodities will really take off.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.