Observations by David Robertson, 9/20/24

Half the week was shot just waiting for the Federal Open Market Committee meeting on Wednesday. Fortunately, there were plenty of other things to noodle on. Let’s dig in.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

The US dollar keeps bouncing around. After it looked like it might be on an upward trend last week, it fell again this week. After a big 50 bp cut by the Fed on Wednesday should have caused further weakness, the dollar actually emerged stronger.

While there are a lot of moving parts, it is hard to not view the recent weakness in the dollar as a tactical effort in front of the election. This runs in contrast to a strong dollar strategy that has persisted through most of the Biden administration.

The big question will be what the plan for the dollar is after the election. Regardless, there will be a new president with presumably a new set of priorities. As a result, it is hard to read too much into the near-term movements.

In an addendum to my report last month that Warren Buffett sold half his stake in Apple, Almost Daily Grant’s (9/12/24) now reports that Ajit Jain, long-time lieutenant of Buffett, “cashed out in a major way on Monday” by liquidating “200 Class A shares for roughly $139 million in proceeds.” Jain has been especially praised by Buffett for his risk management skills. Good to know.

Inflation

In capturing the ethos of the market on inflation, Robert Armstrong declared “Inflation is still dead” in his Unhedged newsletter for the FT ($). He went on to explain that the belief that “there is no particular reason to worry about it [inflation] picking up again” is “not at all obvious when you look at the [inflation] numbers the way we usually do.”

Armstrong isn’t the only one finding data to be uncooperative in validating the “inflation is dead” thesis. Russell Clark goes whole hog in the other direction by declaring “FOOD INFLATION IS BACK!”. He notes:

I am beginning to see upward pressure on food prices emerge. First Chinese pork prices (which is about 20% of all meat in the world, and directly correlated to corn prices) has spiked again … But even more intriguing is that Japanese rice prices are spiking.

He also highlights, “food inflation has had the predictable effect of causing political change.” In other words, politicians can’t afford to just let it go; they have to do something about it.

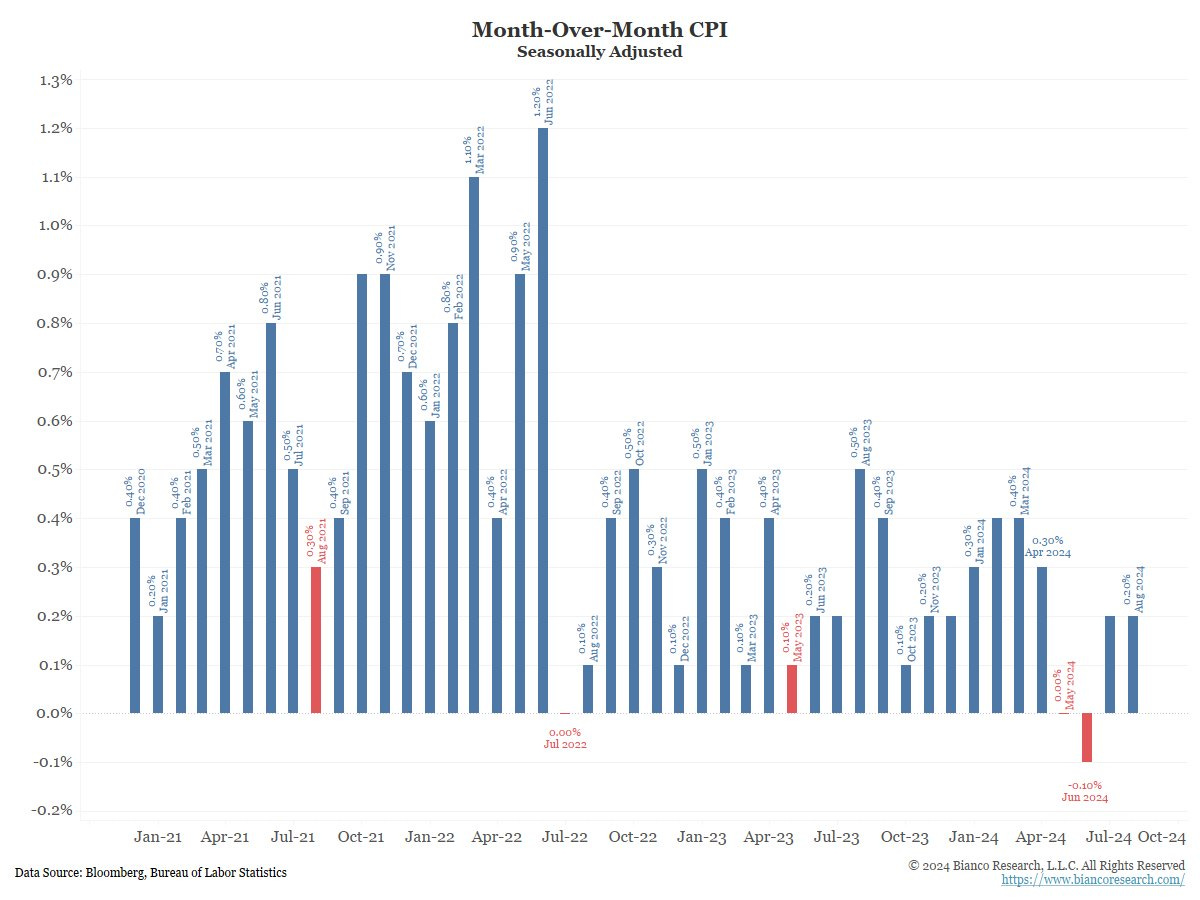

This is happening at the same time Jim Bianco is picking up on seasonal weakness in CPI numbers …

And John Authers is noticing that economic data is starting to improve.

None of this is to authoritatively claim that inflation is currently raging. It is to claim, however, that it is premature to call inflation dead. This is a distinction that matters quite a bit to long-term investors.

On this note, it is at least somewhat serendipitous that John Cochrane recently put out an article that seriously questions a central bank’s ability to manage inflation with interest rates: “there is no simple textbook economic model in which higher interest rates lower inflation slowly over time, without contemporaneous fiscal tightening.” Perhaps a little more humility would be appropriate here.

Credit

Heading into the fall, there are a lot of moving parts in the financial landscape. The Fed has embarked on its journey to lower rates and banks are starting to feel the pain even before widely expected credit problems are considered. Craig Shapiro does a nice job describing the lay of the land:

One issue now for the economy and for markets is the inversion of the curve between FFR [Fed fund rate] and 5yr as many levered banks are still financing themselves at rates closer to FFR (high deposit and cd rates, BTFP facility, etc) and then opportunities for lending out profitably are diminished with 5 year rates so much lower. This is a major NIM problem for banks which JPM noted this week when it took down numbers for 2025. The mortgage refi wave that is coming will also hurt NIMs as higher yielding loans are repaid. And this is before all the delinquency issues from credit risks come that will also hit the banks like ALLY mentioned.

Banks are going to contract credit creation and M2 in this setting, not expand it. That's gonna make things a lot worse until the Fed dramatically and rapidly cuts rates to lower their cost of funding. And given these banks have had massive market cap gains since SVB crisis and there are more facilities in place to aid them should they need it, it's hard to see the Fed feeling like banks are an issue right now that will force massive cuts in a short period until the economy shows more signs of the hard landing. So the slower they go, the worse this will be for the economy and for banks and when banks start to struggle, bad things typically ensue

While banks are less important to the economy today than they used to be, they are still important and the news isn’t good. Their ability to generate margins by borrowing short and lending long are diminished by the yield curve and there is a wave of bad loans coming that will need to be written down. Shapiro is likely right that credit creation will contract - and this in turn will reduce money supply. These are big, foreseeable headwinds for future growth.

While Shapiro focuses on the negatives, arguably, most of them are already priced in to the bond market. As a result, the biggest potential for surprise is on the upside. For example, lower rates may provide an impetus for significant growth in bank loans - which would cause growth in broad money and the economy. In addition, fiscal spending could re-accelerate.

The election adds uncertainty to all this. Policy recommendations differ substantially between the candidates and the probability they get implemented is heavily dependent on Congressional results. For now, the worst bet seems to be placing high odds on a single outcome.

US Consumer

The Car Dealership Guy provided some interesting insights on the consumer:

[NEWS] Car buyers are hitting a wall:

A new survey reveals that many shoppers are facing sticker shock as new car prices average over $47,000 and loan rates stay above 7%.

The disconnect?

The average driver hasn’t bought a car since 2018, when prices were lower, interest rates were better, and dealerships offered more deals.

Now, nearly half of new car shoppers want to spend under $35,000 on a new car — over $10,000 less than the average price.

And used car buyers aren’t catching a break either.

Only 5% of deals are falling under $15,000.

These conditions are forcing consumers to make tough choices: stretch the budget, go smaller, or hold off until the market cools down.

The craziest part?

More than 50% of respondents plan to work more hours or even take on a second job to fund their next car purchase… wild.

For starters, I know I have been experiencing sticker shock more frequently lately and I suspect a lot of other people have as well. This can especially be a problem with relatively big ticket items that are purchased infrequently - like cars. When confronted with such a disconnect between real and expected price, the purchase of a car can usually be deferred, but not indefinitely.

As a result, there is a delayed economic effect. For some period of time, prices continue to ratchet up. But at some point, incomes need to go up, credit needs to become more available, or higher prices result in lower sales.

Two data points stand out. First, there is a huge difference ($10,000) between what “new car shoppers want to spend” and the average price of a new car. Second, consumers have not yet capitulated on buying cars they can’t afford. Thus far they are making up the difference by “working more hours” or by “taking on a second job”. While this strategy could work if pay keeps rising, it is a risky strategy that is vulnerable to any little disruption.

Monetary policy

Going into the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting this week, Jim Bianco highlighted the unusual degree of uncertainty. There were fairly even odds of a 25 bp cut and a 50 bp cut. This is interesting because the Fed’s entire program of forward guidance and increased communication was designed to avoid exactly this kind of scenario - confusion about the Fed is likely to do.

While most of the debate has focused on economic considerations, of which the evidence is mixed, the signaling considerations are extremely important here too. As Chris Giles ($) writes in the FT: “A large cut demonstrates the Fed was behind the curve in July. It signals a crisis of confidence in the central bank and has a whiff of panic about it”. Excellent points.

In addition, the Fed runs a significant risk of reacting asymmetrically to price pressures. When inflation accelerated in 2021, the Fed insisted on labeling it as “transitory” and refused to act. Only later in 2021 did it finally acknowledge it was a problem. Only later the next year did the Fed begin to act by raising rates and initiating Quantitative Tightening. A big pre-emptive cut would send a signal that the Fed is a lot more worried about deflation than inflation. Actions speak louder than words.

When the news finally came out at 2:00 pm on Wednesday, the answer was a 50 bp cut. This sent assets on a wild ride for the rest of the day trying to figure out just what the big cut meant. The 10-year US Treasury yield, for example, rose on the day of the over-sized cut in the Fed funds rate suggesting concern the Fed was too loose.

While clearly there were ulterior motives in deciding on a 50 bp cut to start things off, investors are left wondering what those motives are. Although stocks initially loved the idea of lower rates, a cloud of uncertainty is likely to prevail over risk assets until it becomes clearer where monetary policy stands relative to economic conditions.

Public policy

Alan S Blinder: ‘The stars look like they’re aligning for a soft landing’ ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/7aab21f6-3d92-4103-90ac-a179872c1c6b

Unhedged: You’ve had a long career. What are the biggest things you’ve changed your mind about?

Blinder: One has to do with the overwhelming importance of politics over economics, especially in macroeconomic and fiscal policy — but not in monetary policy, which is one of the reasons I value the independence of the Fed so highly. When I was a young tyke coming out of graduate school, nothing like that was on my mind. But I’ve learned that the politics of the day, including the attitudes and proclivities of the leading politicians and especially the president, are really determinative about what’s going to happen with fiscal policy, much more than economic considerations.

We teach our students in elementary economics that when aggregate demand is too weak, you want to cut taxes and spend more, and when aggregate demand is too strong, you want to raise taxes and spend less. But look at what actually happens in the real world — it’s not so simple. That doesn’t mean the policy is always bad, but it’s not governed by the kind of economic principles that we teach.

This quote by Alan Blinder provides a couple of extremely important insights. First, in the realm of public policy, politics is a far more important determinative factor than economics. This is a hard lesson to stomach for those of us with a lot of education in economics.

I learned a lesson in the GFC when, excepting the prevention of a financial system implosion (which is an important exception, granted), public policy was a disaster from the standpoint of economic utility. It paved the way for years and years of suboptimal growth and distorted incentives. It sounds like Blinder has had similar experiences. His advice reeks of the hard-learned experience of disappointed expectations. Politics trumps economics.

That said, politics tends to go through long cycles that reflect changes in society. During the Reagan administration, for example, the public had grown weary of interventionist policymaking by the government. By the GFC, however, and especially since Covid, people have started favoring progressively more involvement by government in economic affairs.

So, Blinder’s lessons are well-taken. While economics offers a number of ideas and models to better understand and suggest public policy measures, the determination of those measures is not a policy debate. Rather, policy is determined by politics. Analysts and investors will do well to keep this in mind as they handicap the types of measures that are likely to be implemented.

Investment advisory

The ETF Market: A Zine - by Dave Nadig - Echo Beach

https://davenadig.substack.com/p/the-etf-market-a-zine

Most advisors have evolved into ETF-based investing, and the vast majority of them are using some form of model portfolio. As such, they’re usually invested in perhaps a dozen individual tickers across all their clients, and honestly, they’re not out scavenging for the new hotness each day.

Well any big complex system — like the market — that becomes over optimized becomes fragile. It loses its ability to adapt to changes. The problem is that big, fragile systems tend to break in unpredictable ways. I can point to things I’m worried about—leverage, clearinghouse overload, the increasing opaqueness of derivative chain counterparty risk, passive-flow effects — but ultimately nobody can tell you what’s gonna break next. All I can say is — market structure feels fragile, and that means, pay attention.

Dave is one of those rare people in finance who is both extremely knowledgeable and truly wants to help people. As a result, this little presentation on ETFs is one of the best introductory packages an individual investor or advisor could hope for. What a great resource!

Speaking of which, Dave also rightly calls out Michael Kitces, who he calls “the patron saint of actual financial planning”. He describes the website Kitces.com as “pretty much the only place on the internet you’re going to find 10,000 words on the disclosure obligations of ‘Fee Only’ advisors or changes to required minimum distribution rules.” In other words, it provides a lot of useful and relevant information rather than just pictures of retirement-age people sitting on the beach.

Investment strategy

Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, September 13, 2024 ($)

“The Less-Efficient Market Hypothesis,” an eye-opening new essay by Cliff Asness, co-founder of AQR Capital Management, is the cri de coeur of one of the investment world’s foremost theorist-cum-practitioners. “So, yes, depressingly,” Asness admits concerning Mr. Market’s vexing affinity for high valuations and all-American portfolios, “I’m saying you can do the right thing and still be wrong for about 30 years

One important point Cliff Asness makes in his effort to understand the long running outperformance of US stocks vs. international stocks and of growth stocks vs. value stocks is that as improbable as it may sound, the best reason he could find is that stocks are in a bubble.

This is a fairly strong statement on it own, but is far more so given that it is essentially coming from the global headquarters of the efficient market hypothesis at the University of Chicago. In other words, Asness is one of the least likely people in the world to even accept that bubbles exist, let alone to posit that we are in one.

Mike Green ($) picks up the analysis with a couple of embellishments of his own. For one, he argues the approach Asness uses of analyzing the spread between growth and value stocks misses a really important point: value stocks are expensive too! As Green puts it, “you know what’s REALLY expensive versus 2000? Cliff’s value stocks”.

Green also criticizes Asness for concluding social media is the mechanism by which the bubble was enabled. As Green explains, “it would not be enough for social media to have steered everyone except for Cliff wrong, they would need enough money (capital) to affect prices in this universal way.” True enough. Further, “social media” seems like a mighty thin reason for justifying such a large and important market inefficiency.

Regardless, the Asness research provides some helpful insights for long-term investors. First, US stocks are really, really expensive. This means there is a lot of downside and/or expectations of very poor future returns. If you believe Green (which I do), this also applies broadly to value stocks.

Second, market anomalies can persist for long periods of time - even thirty years! This means sticking by a strategy can require enormous amounts of patience. It also means that most research is superficial if not outright misleading - because it covers periods too short to capture the full breadth of potential market conditions. In short, it’s conditional.

Finally, in a broader sense, the Asness research seeks to provide some assurance of the value of financial research. There are good, well-researched reasons why value stocks should perform well over time and why international stocks can be valuable diversifiers. It would be a shame to give up on these ideas at exactly the wrong time.

Implications

The Substacker Alyosha published a quote by Alex Manzara that captures the reaction function of the Fed pretty well: “[Post-election] comes with heaps of uncertainty and the Fed addresses uncertainty with liquidity.” Fact check: True.

A great deal of that uncertainty is related to the nature, timing, and quantity of fiscal support for the economy and that of course, depends significantly on who wins the election. While a great deal of attention right now is being placed on economic weakness, I think the bigger deal for long-term investors is going to be the degree to which government policy responses favor labor or favor capital.

We already know the Fed’s default response is to lower rates - which favors capital. Will the government policy response be large enough and focused enough to turn the tables in favor of labor? If not, expect stocks to continue basking in the glow of the Fed’s attention and perhaps reach even greater highs. If so, expect lots of measures to help out workers and consumers, expect business costs to go up, and expect inflation to start rising again.

Even in the event government policy does not come out clearly in favor of labor right away, however, I suspect it will just be a matter of time. Low rates don’t boost economic growth or improve consumer demand. That lesson has been learned. As a result, for however long a relatively low inflation environment endures, it will mainly be setting the stage for higher inflation over the longer-term. Good to keep in mind for portfolio allocations.

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.