Observations by David Robertson, 9/6/24

It was a short week but an eventful one. Let’s jump right in.

As always, if you want to follow up on anything in more detail, just let me know at drobertson@areteam.com.

Market observations

Stocks opened weak on Tuesday with a doozy of a hangover from the long holiday weekend. They continued to tumble into a weak ISM report at 10:30, stabilized for a while, and then continued their descent through the afternoon.

While the signs of economic weakness didn’t help, the selloff was driven by Nvidia. The downturn in Nvidia can be attributed to a lot of things, not least of which is the peak in the semiconductor cycle mentioned last week. The selloff, however, was also just some give back from extremely overbought conditions.

On Wednesday, Alyosha reported, “Durable goods orders are up nearly 20% in 2 months. Either that’s a bad thing (higher rates) or the JOLTS report is a bad thing (lower rates) but they can’t both be the same thing.” This is a good example of the contrast between mixed readings on the economy and sentiment that is heavily skewed to the negative side at the moment.

On Thursday, John Authers highlighted a similar disconnect with rate expectations. With stocks near all-time highs and the GDPNow estimate at 2.1%, there is nothing in markets saying the bottom of the economy is dropping out. And yet, the market is pricing in the most aggressive set of cuts in at least 34 years:

Finally, with sentiment homing in on signals of weakness in the economy, all eyes were on the jobs report on Friday morning. Bob Elliott previewed the release in a thread with the assessment: “there aren't really many signs that the labor markets are deteriorating rapidly at this point. At worst it looks a bit softer than the torrid '22/'23, but pretty stable.”

The payrolls report proved Elliott right; it came in a little weak relative to consensus, but like so many economic reports this year it gave little support for either a very positive or a very negative take on the economy. That said, it didn’t provide enough ammo to change any minds that were already made up either.

Economy

Although stocks were already falling on Tuesday when the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) manufacturing report came out, the report further stoked the fears of traders. The subtitles of the report highlighted the concerns:

New Orders and Backlogs Contracting

Production and Employment Contracting

Supplier Deliveries Slowing

Raw Materials Inventories Expanding; Customers’ Inventories Too Low

Prices Increasing; Exports and Imports Contracting

Not only was business activity contracting, but input costs were also increasing. These are the makings of stagflation, one of the worst of economic diseases. It was not welcome news by any stretch.

That said, there are plenty of reasons to treat the news with a grain of salt. For one, it’s just one report. For another, the ISM report is not one of the better indicators of economic progress. For yet another, manufacturing, albeit an important part of the economy, is only a small part of the overall economy in the US.

In sum, the reaction to the report probably says more about exaggerated expectations for a “goldilocks” economy than it reveals any particularly surprising detail about the economy itself. On that note, expectations are high throughout financial markets - which provides a lot of room for disappointment.

Credit

August --> September

https://www.shrubstack.com/p/august-september

Unlike the Equity Monkeys, who usually get margin-called during the Summer months, the Credit Monkeys do like to take proper Holidays and there is a backlog of new paper that waits for them when they come back after Labor Day. As a result, the Credit Market does tend to have a pretty bad September AND October, as the new paper gets digested.

Take a look at the Seasonality chart of TLT (Ultra-long Bond ETF) and note that during the last 10 years, there were only TWO out of TEN instances of positive returns for TLT in September and also in October!

The Substacker, Le Shrub, makes a couple of important points about the credit market going into the fall. First, there is seasonality to the credit markets. As he notes, a big part of the reason for this is because “September is usually the 2nd biggest month of the year for corporate bond supply, with $135bn of issuance on average in the past 4 years (source: BofA)”. In other words, there is usually a disproportionate amount of supply after the quiet summer months.

Second, the negative effects of credit seasonality also usually make their way into the stock market with September stock seasonality being even worse than in August. This year could be especially challenging because just as yields come under pressure from seasonal supply, so too are credit spreads at risk of rising as bankruptcies and default risks rise.

Of course, these seasonal influences may just be a passing storm. But, given extremely tight credit spreads and a fairly benign fixed income environment overall, seasonality may also be the impetus to swing the pendulum in the other direction for a while.

Geopolitics

How national security has transformed economic policy ($)

https://www.ft.com/content/6068310d-4e01-42df-8b10-ef6952804604

Over the past decade, there has been a much greater willingness to use tariffs as part of industrial and trade policy. Under Biden, there has also been a parallel emphasis on employing subsidies and other forms of state intervention to boost investment in key sectors.

This process is being turbocharged by the way that security issues are becoming entrenched in US government thinking about large segments of the economy, from manufacturing to new technologies.

But the biggest factor has been China. US officials have watched with awe and trepidation at the advances of Chinese state capitalism in many of the industries that are likely to dominate the first half of this century. Retaining and restoring American manufacturing competitiveness has come to be seen as a defining geopolitical challenge.

This FT article provides a good synopsis of how geopolitics has woven its way into public policy by way of national security concerns. It also outlines some of the important consequences of that evolution.

For starters, the rising importance of national security is a bipartisan phenomenon. As a result, its continuation is not dependent on the outcome of the election. According to the FT, “As the presidential election looms, America’s allies are braced for a further intensification of these policies, regardless of the winner.”

In addition, while the rising prominence of national security as a driving force of policy started in China and the US, it’s not likely to stop there. A former White House official described, “The Biden team has created a playbook here that other countries are likely to follow.”

Finally, the cause of national security can be a powerful enabler. For one, an enormous range of activities can be included under its auspices. As Daniel Drezner, professor of international politics at Tufts University, points out, “The trend is everything is a national security issue”.

For another, national security permits wide latitude for justifying actions with otherwise weak pretense. As the article notes, “There is a real risk of calling everything national security and using it to justify doing whatever you want.” Indeed, the threat of “weapons of mass destruction” as an excuse to invade Iraq in 2003 is a notorious, and relatively recent example.

Along these lines, and consistent what I have described repeatedly over the last couple of years, geopolitics is becoming an increasingly important aspect of the investment landscape, largely because of the types of extreme actions that could potentially be implemented for the sake of “national security”. Further, it is all-too-easy to imagine “national security” being invoked in order to implement “emergency” policies to contend with market turmoil, economic downturn, geopolitical squabbling, you name it.

While national security is certainly a valid concern for government, it also provides a ready-made excuse to deal with a lot of other problems as well.

Investment landscape

Pusillanimous Powell ($)

https://www.yesigiveafig.com/p/pusillanimous-powell

I also think Powell’s pusillanimity … will rear its head this fall as seasonal inflation adjustments are likely to result in a “resurgence” of inflation just as Powell makes his first cuts. Similar issues in 2008 led to Bernanke (and Trichet) failing to realize the severity of the deflationary pressure. To help gauge the possible impact, recognize that these seasonal distortions could raise reported inflation in December by several percentage points on an annualized basis.

My analysis suggests Powell has created a trap for himself—cutting interest rates modestly from these levels will not help the indebted and will harm the wealthy. A seasonal resurgence of inflation (which has HELPED the transitory case over the summer, but will reverse into Q4) will lead him to be less aggressive in cutting rates, further increasing the risks of the “phase change” of credit defaults. Once the indebted default, they become economic pariahs for the proverbial “seven lean years.” And those most at risk are again the young:

Now that it is fairly clear the Fed is ready to start cutting rates, the challenge, and potential opportunity, is to determine what the effect those cuts are likely to have on financial markets. As usual, Mike Green offers a thoughtful analysis. Also as usual, his thinking runs counter to consensus.

For starters, Green views the inflation data as being far less supportive of cuts than the Fed does. Just as seasonal inflation adjustments likely overstated the moderation of reported inflation over the summer, they are likely to swing reported inflation higher later this year. This could very well put the Fed in the awkward position of beginning its transition to lower rates just as inflation begins picking up again.

Regardless of whether the Fed gets wrongfooted on inflation, it is still severely constrained in what it can do to improve market conditions. The more it lowers rates, the more it lowers income for the relatively well off who earn interest on cash balances. This has a disproportionately negative affect on the economy since “the income effect is MULTIPLES of the wealth effect”. In short, the more the Fed cuts, the more it also cuts growth.

At the same time, unless the Fed lowers rates a lot, and quickly, debt service burdens will not be eased enough to prevent a continued upswing in defaults and increasing credit impairment. While credit has held up well to date, once it begins to roll over, the Fed can be expected to become hyper-attentive. When that process begins, inflation concerns will go out the window and it will be all hands on deck to preserve financial stability.

So, pretty much regardless of what the Fed does, it will have a hard time stimulating growth without detracting from it at the same time. The dramatic “pre-game” theatrics are over and now its game time. Unfortunately, as often happens with highly anticipated events, the main event is anticlimactic relative to the build up. At this point, there isn’t much left to do other than watch the Fed flounder in conditions it was instrumental in establishing.

Investment strategy I

Fed Pivots and Baby Aspirin

https://www.hussmanfunds.com/comment/mc240830/

Doesn’t an expected Fed pivot make long-term bonds much more attractive? Well, we can ask this question: what is the median change in the 10-year Treasury yield in the first 12 months following a Fed pivot, in a rate-cutting cycle that takes the Fed funds rate at least 150 basis points lower? The answer is zero.

In anticipation of a rate cutting cycle by the Fed, investors and advisors are looking to options to preserve income as short-term interest rates are likely to come down. One of the most obvious options is extending duration by buying longer-term bonds.

As John Hussman makes clear though, the case for long-term bonds is weak at best. For one, long-term bond yields are modestly unattractive relative to growth and inflation. For another, long-term yields historically have not come down after a Fed pivot unless rates were already extremely high - which they are not currently.

So, investors looking to redeploy cash in order to preserve returns would do well to consider the alternatives. With long bonds being not especially attractive and with stocks near all-time highs, one possibility is to just wait for better opportunities. Sure, short-term rates are likely to come down, but they haven’t yet and they may not fall as rapidly or as far as the market currently expects. Plus, cash always has option value for exploiting opportunities that may arise.

Another thing to consider is inflation. At the moment, sentiment is skewed heavily towards rapidly moderating inflation. However, that sentiment is based on just a couple months of data - data that could prove anomalous in the broader context of the remainder of the year. Locking in heavily skewed sentiment for the long-term is a risky bet.

Perhaps the greatest interest in long bonds is driven by the anticipation of a repeat of the 2010s experience of an extended period of falling long-term rates - which drove significant appreciation in long-term bonds. First, that experience is highly unlikely to repeat in the current investment landscape. Second, that would be a highly speculative activity and not one that is appropriate for long-term investment purposes.

Investment strategy II

Last week I wrote that it’s time to start getting prepared for a long run in commodities. Since then, I went through the Goehring and Rozencwajg second quarter report which argues the cost of being late to a commodities rally is greater than the cost of being early.

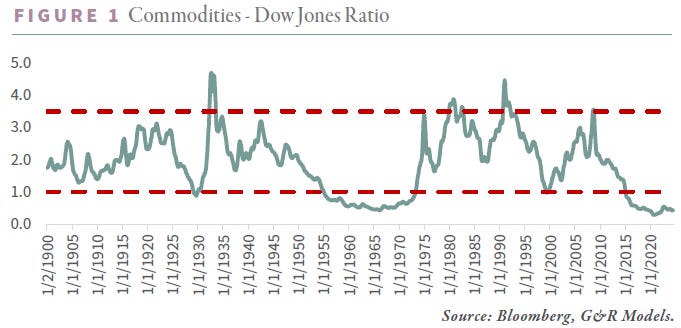

Their study uses several signals of which the Commodities - Dow Jones Ratio is the most intuitive. Accordingly, commodities are an attractive buy for longer-term investors when the ratio drops below 1.0.

One point is the cost of getting in late is substantial because once commodities get so cheap relative to stocks as to break the 1.0 threshold, the recovery is typically fast and furious. Another point is that even when it takes several years for commodities to break back above the 1.0 threshold, as it did in the mid 1950s to early 1970s, when they did break they still broke hard relative to stocks. This made it very difficult to manage commodities in a tactical, rather than strategic, manner. If you’re just a little late, you miss most of the outperformance.

These characteristics also reveal challenges and opportunities for investors. Short-term, tactical investors may be able to catch enough of a commodity wave to make it worthwhile, but at least as often as not they will be late to the party.

Long-term investors, however, who can accept extended periods when commodities don’t do much relative to stocks, will be in a position to fully realize the benefits of commodities when they do break. Not only does this provide some nice incremental returns, but by doing so at the right times also provides a nice diversification benefit.

Commodities present an especially interesting proposition right now. On one hand, because the commodity-Dow ratio is well below 1.0, long-term investors should be seriously considering commodities. On the other, as economic data continues to come in weak, the potential for short-term weakness in commodities is significant. While a certain amount of trepidation is understandable, these conditions also present opportunities to build positions at very attractive prices.

Implications

One of the big challenges with any financial assets right now is that positioning is so aggressive. Whether it is by way of leverage to build bigger positions or simply exposure to risk assets instead of cash or safer assets, investors of all types are making bets that risk assets will continue performing well. If, for whatever reason, confidence in risk assets begins to ebb, selling pressure would ensue regardless of fundamental conditions.

This was evident in the selloff on August 5th amid what was proclaimed as the yen carry unwind. However, it was also evident on Tuesday in the selloff of Nvidia and the selloff in gold stocks, among others. The point is there is “hot” money almost everywhere that poses a risk for would-be buyers. As a result, it makes sense to tread carefully when seeking to deploy cash.

Another big challenge with financial assets is outlining what the post-election future holds for them. From one perspective, there is the normal level of uncertainty associated with a close election and the different policy priorities that will emerge afterwards.

From a higher level perspective, however, there is also a wide array of risks that threaten to severely constrain any administration. For starters, there is a good chance vote recounts and/or a contested election will extend uncertainty for a considerable period of time. For another, debt ceiling theatrics will start up promptly in January. In addition, low income wage earners will continue to struggle which will create loud political demands. For yet another, the slow-motion train wreck that is commercial real estate is likely to pick up speed as debt fails to get rolled over. At the same time, geopolitical tensions, which have been simmering, have the potential to boil over at any moment.

As a result, the big question for risk assets will be what types of “emergency” policies are likely to emerge from this quagmire? While the realm of specific policies is wide open, there are some general outlines that are useful.

For example, financial stability will remain a top priority. As such, a spiraling debt deflation is unlikely. In addition, the political trend of favoring labor over capital is likely to continue. This is likely to manifest in higher wages (for workers to spend) and greater constraints on corporate behavior. So, while deflationary forces are likely to pick up in some areas, they will mainly serve as the impetus for new policies that prove inflationary. Good luck!

Note

Sources marked with ($) are restricted by a paywall or in some other way. Sources not marked are not restricted and therefore widely accessible.

Disclosures

This commentary is designed to provide information which may be useful to investors in general and should not be taken as investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to any individual’s or organization's particular financial circumstances. As a result, any action you may take as a result of information contained on this commentary is ultimately your own responsibility. Areté will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information.

Some statements may be forward-looking. Forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date such information was originally posted. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Areté disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein.

This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Areté is not responsible for any third-party content that may be accessed through this commentary.

This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written permission of Areté Asset Management.